Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Emanuel Melgarejo-Estefan1, Daniel Lopez-Hernandez2*, Leticia Brito-Aranda3, Tabata Gabriela Anguiano Velazquez4, Rocio Loa Gutierrez4, Aline Vanessa Carrera-Vite5, Liliana Grisel Liceaga-Perez5, Abraham Espinoza-Perdomo6, Alberto Vazquez-Sanchez7, Perla Veronica Salinas-Palacios8 and Maria Clara Hernandez Almazan9

Received: January 06, 2025; Published: January 28, 2026

*Corresponding author: Daniel Lopez-Hernandez, Family Medicine Clinic Division del Norte, Institute of Social Security and Services for State Workers (ISSSTE), Mexico City, Mexico

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2026.64.010058

Background: Primary care addresses most essential health needs, including the prevention and management of

communicable and non-communicable diseases. Understanding the demographic and epidemiological profile of

patients is essential for guiding preventive and integrated care.

Methods: We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional, analytical study using data from the Medical Financial

Information System (SIMEF) at the Family Care Clinic Cuajimalpa (ISSSTE), in Mexico City. All patients

who attended outpatient consultations from January to December 2024 were included (n=7,857). Sociodemographic

characteristics, age- and sex-specific population distribution, and ICD-10–coded non-communicable and

communicable diseases were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics test, as appropriate.

Results: The study population was predominantly female (62.8%). Age distribution showed a constrictive population

pyramid with the largest groups in middle and older adulthood, particularly 50–69 years old. The mean

age was 49.2 years old (SD=21.3). The most prevalent non-communicable diseases were hypertension (22.1%),

diabetes (21.2%), dyslipidaemia (11.1%), intestinal malabsorption (7.6%), chronic venous insufficiency (7.1%),

and low back pain (7.1%). Sex differences included higher rates of obesity, hypothyroidism, chronic venous insufficiency,

gonarthrosis, and dorsalgia in females, and higher hypertension and diabetes prevalence in males.

The five most frequent communicable diseases were acute pharyngitis (10.7%), urinary tract infection (6.8%),

unspecified infectious gastroenteritis (4.1%), conjunctivitis (1.9%), and acute nasopharyngitis (1.8%), with females

showing higher rates of pharyngitis and urinary tract infection. Besides, monthly consultations exhibited

seasonal peaks in July, August, and October, driven primarily by female attendance.

Conclusion: Patients attending primary care present a substantial burden of both non-communicable and communicable

diseases, with pronounced age- and sex-specific patterns. These findings highlight the need for lifecourse,

sex-sensitive, and integrated strategies to optimize preventive care, early detection, and comprehensive

management in urban primary care settings.

Keywords: Communicable Diseases; Morbidity; Non-Communicable Diseases; Primary Care

The utilisation of health services at the primary care level represents a fundamental component of healthcare systems worldwide, as it constitutes the first point of contact between population and formal health services [1-3]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), effective primary healthcare can address up to 80 % of essential health needs across life course, particularly for the prevention, diagnosis, and management of both communicable and non-communicable diseases [2,4-6]. Globally, outpatient consultations at the primary care level are predominantly driven by chronic conditions, acute respiratory infections, gastrointestinal diseases, and urinary tract infections, reflecting the ongoing epidemiological transition observed in low- and middle-income countries [7-11]. In Americas’ Region, data from the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) indicate that non-communicable diseases account for most primary care visits, especially cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, while communicable diseases remain a frequent cause of consultation, particularly in children, older adults, and women [12-14]. Similar patterns have been documented in the United States, where national ambulatory care surveys show that primary care services are largely utilised for the management of chronic metabolic conditions, musculoskeletal disorders, and common infections, with marked differences by age and sex [15,16].

These findings are consistent with global health surveys, which highlight the increasing demand placed on primary healthcare systems by ageing populations and the rising prevalence of chronic diseases [17,18]. In Mexico, national health surveys such as the Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición (ENSANUT) consistently report high utilisation of primary care services, particularly among adults and older adults, driven mainly by cardiometabolic diseases and their complications [19-21]. At the same time, infectious diseases such as acute respiratory infections, gastrointestinal infections, and urinary tract infections remain among the leading causes of outpatient consultations, underscoring the coexistence of chronic and infectious disease burdens [22-26]. Therefore, characterising the sociodemographic and epidemiological profile of individuals attending primary care services is fundamental for identifying prevailing health needs, patterns of service utilisation, and sex- and age-related disparities. Accordingly, this study aimed to describe the sociodemographic profile of a population attended at a primary care unit and to analyse the epidemiological distribution of communicable and non-communicable diseases among individuals receiving care at the first level of healthcare in Mexico City.

Study Design and Data Collection

The present study was designed as a population-based, cross-sectional, and analytical investigation. The data included patients from the western area of Mexico City who attended outpatient consultations at the Family Care Clinic/Office Cuajimalpa, Institute of Social Security and Services for State Workers (ISSSTE; Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado, by its acronym in Spanish), Mexico City, Mexico. The dataset was extracted from the Medical Financial Information System (SIMEF), which systematically records outpatient consultations provided by healthcare personnel. We included medical records from January to December 2024. The complete database is consisting of 35,872 records corresponding to 7,857 persons of all age groups. The study was conducted from 1st July to 30st November, 2025.

Patient Selection and Study Population

The data collection procedure included the following steps: 1. A single Excel file covering the period January–December 2024 was generated and downloaded from the SIMEF system. During this initial step, records corresponding to consultations that were not provided were identified and removed.

2. A unified database was then constructed, and all individual patient records were cross-referenced to verify internal consistency across variables, prevent duplication of information within each variable, and ensure that individual patients were not duplicated in the dataset.

3. A validation process was subsequently performed to ensure the integrity, accuracy, and completeness of the dataset. 4. The cleaned and validated dataset was stored in an Excel workbook, which served as the statistical dataset for subsequent epidemiological analyses.

Inclusion Criteria:

1. Individuals with at least one consultation registered in the SIMEF system during the study period.

2. Complete clinical records, including identification variables (name, file number, sex, beneficiary type), International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) diagnosis code(s), and consultation dates.

Exclusion Criteria:

1. Records that were incomplete, inconsistent, or lacked essential identification or diagnostic information in the SIMEF system.

2. Duplicate records identified during data cleaning. Finally, a census sampling method was employed, with all eligible records from the newly generated dataset. All this ensured that only patients with complete and consistent records were included in the study.

Variables and Statistical Analysis

The variables analysed comprised age (in years), sex (male and female), number of outpatient consultations, and comorbidities coded according to the ICD-10. In total, 1,132 ICD-10 codes were registered. New variables were generated to identify obesity, dyslipidaemia, diabetes, and age groups. For obesity, the following ICD-10 codes were included: E66.8 –Other obesity; and E66.9 –Obesity, unspecified. For dyslipidaemia, the selected codes were: E78.0 –Pure hypercholesterolaemia; E78.1 –Pure hyperglyceridaemia; E78.2 –Mixed hyperlipidaemia; E78.4 –Other hyperlipidaemia; E78.5 –Hyperlipidaemia, unspecified; E78.8 – Other disorders of lipoprotein metabolism; and E78.9 – Disorder of lipoprotein metabolism, unspecified. Diabetes was identified using the following ICD-10 codes: E10.1–E10.9 and E11.0–E11.9, encompassing type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus and their related complications. Age was categorised using a hierarchical epidemiological approach. The study population was first divided into four main age groups: children (0–9 years old), adolescent population (10–19 years old), mature population (20–59 years old) and elderly population (≥60 years old). Children were further classified into neonates and infants (0 years old), early childhood (1–4 years old), and childhood (5–9 years old). The adolescent population was subdivided into early adolescence (10–14 years old) and late adolescence (15–19 years old).

The mature population was stratified into early adulthood (20–39 years old) and midlife (40–59 years old). Finally, the elderly population was disaggregated into sexagenarians (60–69 years old), septuagenarians (70–79 years old), octogenarians (80–89 years old), nonagenarians (90–99 years old), and centenarians (≥100 years old). Categorical variables are presented as absolute frequencies and percentages, while quantitative variables are described using mean, standard deviation (SD), range, maximum value, minimum value, median, and interquartile range (IQR). A 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was reported where applicable. Comparisons of categorical variables were performed using the likelihood ratio and the Yates’ continuity correction chi-square (χ²) (LRχ² and Yχ², respectively), as appropriate. Quantitative variables were compared using U Mann-Whitney test, and Median Test between independent groups. The age distribution was analysed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with Lilliefors correction. A two-tailed p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

The present study was conducted in compliance with the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, national regulations, and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects. The Data was treated confidentially. To guarantee confidentiality, only the principal investigators had access to the complete dataset, including identifiable patient information (e.g., names). The patient names were replaced with unique identification numbers. The assigned number allows the data to be linked to a specific individual without revealing the individual’s identity. This approach ensured that all patient data were handled under ethical standards and maintained the highest level of confidentiality throughout the study. This anonymization was conducted before sharing the dataset for statistical analysis with some researchers. After the statistical analysis, only the processed statistical data was made available to the rest of the research team.

Characteristics of the Study Population A total of 7,857 individuals were included in the study. Of the total population, females constituted the main group with the highest healthcare utilisation, comprising 4,936 participants (62.8%; 95% CI: 61.8–63.9), compared with 2,921 males (37.2%; 95% CI: 36.1–38.2). To further characterise this distribution, an analysis of the population pyramid was conducted to illustrate the demographic composition of the study population by age group and sex. This structure supports the interpretation of population dynamics that are closely linked to patterns of morbidity, healthcare demand, and differential health risks across age strata. Our population pyramid shows a marked concentration of individuals in the middle and older adult age groups, particularly between 50 and 69 years old, indicating an ageing population structure. Females consistently outnumber males from mid-adulthood onwards, particularly in age groups above 70 years old. In contrast, the younger age groups, particularly children and adolescents, represent a comparatively smaller proportion of the population, resulting in a narrow base of the pyramid. The age– and sex– distribution corresponds to a constrictive (regressive) population pyramid, characterised by a narrow base and a relative expansion of the middle and older age groups. This structure reflects reduced representation of younger cohorts and a concentration of individuals in adulthood and later life (Figure 1).

The average age, in overall population, was 49.23 (Figure 2) years old (SD=21.33, range=100, minimum age=0, maximum age=100 years old, median age=53 [IQR=35-65]). The age distribution is non-normal and exhibits a bimodal pattern, with a dominant peak in middle-to-older adulthood and a secondary peak in younger ages. This structure suggests the presence of distinct age-related subpopulations, likely reflecting differential healthcare utilisation patterns across the life course. This age distribution was demonstrated by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with Lilliefors correction (D = 0.078, p < 0.001). In addition, the average age of the subjects between sexes was similar (males=49; versus females=49.37; p=0.162, using U Mann-Whitney test). However, the median age was higher in males (54 years old; IQR= 34-66) compared to female (52 years old; IQR=36-64; p<0.001, Median Test between independent groups). The convergence of statistical testing and graphical analysis reinforces the interpretation of an ageing study population with heterogeneous age-related healthcare needs. On the other hand, Table 1 presents age- and sex-distribution of the study population, providing an overview of the demographic structure of the population. Most participants were concentrated in the sexagenarian population, followed by individuals in midlife, whereas young adults constituted a smaller segment of the study population.

Note: Prepared by the authors using the results from the SIMEF database, January-December, 2024. EA: early adulthood (20-39 years old). ML: midlife (40-59 years old). EP: elderly population (60 years old and over). N&I: neonates and infants; EC: early childhood; AP: adolescent population; EA: early adolescence; LA: late adolescence; MP: mature population. Comparisons among age group (Children, AP, MP, and EP) and sex was performed using the Likelihood Ratio chi-square (LRχ²=110.226, df=2, p<0.001). Comparisons among age group (N&I, EC, Chilhood, EA, LA, EA, ML, sexagenarians, septuagenarians, octogenarians, nonagenarians, and centenarians) and sex was performed using the Likelihood Ratio chi-square (LRχ²=123.404, df=11, p<0.001).

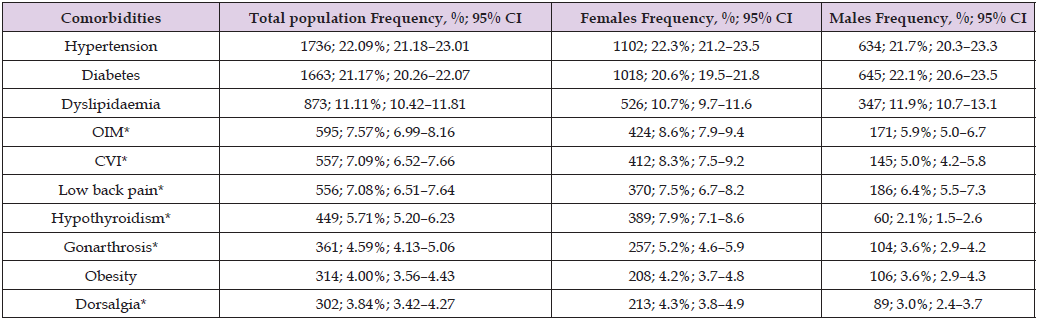

A higher proportion of females was observed across nearly all age groups, except for early adolescence, where males predominated, and early childhood, where sex-specific proportions were similar. This pattern underscores the importance of integrating sex- and age-specific approaches in preventive and healthcare strategies for the management of communicable and non-communicable diseases. Monthly outpatient consultation counts showed a consistent predominance of females across all months of the year. In both sexes, consultation volumes followed a similar temporal pattern, with lower activity during the first quarter and a steady increase from spring onwards (Figure 3). Three distinct peaks in consultation demand were observed, occurring in July, August, and October, with the highest volumes recorded in August and October. These peaks were largely driven by increased female attendance, while male consultations rose in parallel but remained consistently lower throughout the year. This pattern reflects sustained sex-based differences in healthcare utilisation alongside clear seasonal fluctuations in outpatient service demand. Table 2 presents the epidemiological profile of the ten most prevalent non-communicable diseases of the total study population, followed by a sex-based comparative analysis. In the overall population, hypertension was the most prevalent condition, followed by diabetes and dyslipidaemia.

Table 2: Overall epidemiological distribution and sex-based comparison of the ten most frequent non-communicable diseases in the study population.

Note: Prepared by the authors using the results from the SIMEF database, January-December, 2022. CVI: chronic venous insufficiency. OIM: other intestinal malabsorption. Comparisons between sex were performed using the Yates’ continuity correction chi-square (Yχ²); degree freedom (df). *P values statistically significative. Hypertension (Yχ²=0.376, df=1, p=0.540); diabetes (Yχ²=2.250, df=1, p=0.134); dyslipidaemia (Yχ²=2.657, df=1, p=0.103); *OIM (Yχ²=19.234, df=1, p<0.001); *CVI (Yχ²=31.370, df=1, p<0.001); *low back pain (Yχ²=3.383, df=1, p=0.066); *hypothyroidism (Yχ²=114.552, df=1, p<0.001); *gonarthrosis (Yχ²=10.973, df=1, p=0.001); obesity (Yχ²=1.488, df=1, p=0.223); *dorsalgia (Yχ²=7.648, df=1, p=0.006).

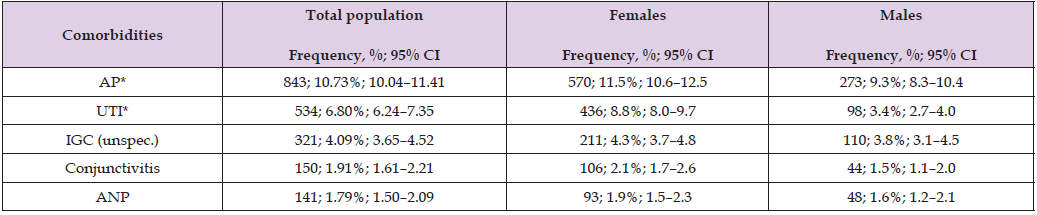

Other intestinal malabsorption, chronic venous insufficiency, and low back pain occupied intermediate positions in the prevalence ranking, whereas hypothyroidism, gonarthrosis, obesity, and dorsalgia were less frequent. When stratified by sex, females exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of other intestinal malabsorption, chronic venous insufficiency, hypothyroidism, gonarthrosis, and dorsalgia compared with males. Conversely, none of the evaluated conditions were significantly more prevalent in males compared with females. Finally, no statistically significant sex-based differences were observed for hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, low back pain, or obesity, indicating a comparable burden of these conditions between women and men in the study population. Table 3 presents the overall epidemiological distribution of the five communicable diseases with the highest prevalence in the study population, followed by a sexbased comparative analysis. In the total population, acute pharyngitis showed the highest prevalence, followed by urinary tract infection and unspecified infectious gastroenteritis and colitis. Conjunctivitis and acute nasopharyngitis showed lower prevalence. When stratified by sex, acute pharyngitis and urinary tract infection had a significantly higher prevalence among females than males. In contrast, no statistically significant sex-based differences were observed for unspecified infectious gastroenteritis and colitis, conjunctivitis, or acute nasopharyngitis.

Table 3: Overall epidemiological distribution and sex-based comparison of the five most frequent communicable diseases in the study population.

Note: Prepared by the authors using the results from the SIMEF database, January-December, 2022. AP: acute pharyngitis; UTI: urinary tract infection; IGC (unspec.): other and unspecified gastroenteritis and colitis of infectious origin; ANP: acute nasopharyngitis [common cold]. Comparisons between sex were performed using the Yates’ continuity correction chi-square (Yχ²); degree freedom (df). *P values statistically significative. *AP (Yχ²=9.059, df=1, p=0.003); *UTI (Yχ²=86.070, df=1, p<0.001); IGC (unspec.) (Yχ²=1.086, df=1, p=0.297); conjunctivitis (Yχ²=3.693, df=1, p=0.055); and ANP (Yχ²=0.475, df=1, p=0.491).

The structure observed in the population pyramid in the present study reflects a demographic profile characteristic of populations undergoing an advanced epidemiological transition. When compared with global and regional population pyramids, this structure shows a relative narrowing of younger age groups and a marked expansion of middle-aged and older adult cohorts, a pattern increasingly documented in middle-income countries [27-29]. At the global level, the contemporary population pyramid demonstrates a gradual shift from a traditionally expansive shape towards a more rectangular configuration, driven by declining fertility rates and increasing life expectancy [30]. This global trend is accompanied by a growing proportion of individuals aged 40 years old and older, particularly in the 50–69 and ≥70-year age groups, which has substantial implications for disease burden and healthcare demand [31-34]. Our population structure aligns with regional and global demographic dynamics, indicating that the transition we describe is part of a wider epidemiological phenomenon rather than an isolated local occurrence [27,34,35]. However, important contrasts emerge when comparing this pyramid with other specific world regions. In Africa, population pyramids remain predominantly expansive, with a wide base reflecting high fertility rate and a comparatively small proportion of older adults, a demographic context associated with a higher relative burden of communicable diseases and maternal–child health conditions [36].

In contrast, Europe exhibits a markedly constrictive pyramid, characterised by low proportions of children and a substantial accumulation of older adults, particularly those aged ≥65 years old, reflecting long-standing low fertility and advanced population ageing [37]. Asia and Latin America occupy intermediate positions along this demographic continuum. While both regions have experienced rapid fertility declines, their pyramids still retain relatively broad working-age cohorts, particularly among adults aged 30–59 years old [38-40]. This configuration has been described as a transient phase in which the demographic dividend coexists with an accelerating ageing process [41]. The age distribution observed in our study population is closely aligned with this transitional profile, particularly resembling patterns reported in Latin American populations. In comparison with North America and Oceania, where population pyramids are increasingly rectangular with pronounced upper-age expansion, the structure observed in our study shows a slightly less accentuated ageing pattern but a clear concentration in middle and older adult age groups [42-45]. This suggests a demographic stage in which ageing- related health needs are already prominent, even if the oldest-old population has not yet reached the proportions observed in high-income regions [45,46].

In Mexico, overall population pyramid exhibits a predominantly stationary-to-constrictive structure, characterised by a progressive narrowing of younger age groups and an expanding proportion of adults in middle and older age strata [46]. In comparison, the population pyramid derived from our study population is consistent with the demographic profile reported in primary care–based studies from urban Mexico, where service utilisation is dominated by adults in working and post-working ages rather than younger cohorts [26]. National demographic data indicate that approximately one quarter of the Mexican population remains under 15 years of age, while the majority is concentrated in the 15–64-year age group, and a smaller but steadily increasing proportion corresponds to adults aged 65 years oldand older [46]. In contrast, the population attending the FMC División del Norte [26] and the cohort analysed in the present study display a higher representation of adults aged 30 years old and above, particularly within the 40–69-year old range, which differ to observed in the general population structure of Mexico. This divergence between the clinical and national population pyramids is epidemiologically expected. While the national pyramid reflects the demographic composition of the entire population, clinical populations—especially those attending primary care services—represent age groups with higher healthcare needs.

Adults and older adults are more likely to seek medical attention due to chronic disease burden, functional limitations, and cumulative exposure to risk factors, whereas younger individuals, despite constituting a substantial proportion of the general population, contribute less to outpatient service demand. Moreover, the similarity between our population pyramid and that reported for the FMC División del Norte further supports the representativeness of our study population within the context of urban primary care in Mexico City. Both populations exhibit age structures indicative of an advanced epidemiological transition, with dominance of adult cohorts and an expanding older population segment. This alignment reinforces the interpretation that the disease patterns identified in our study are not artefactual but rather reflect the demographic realities of populations accessing primary care services in metropolitan Mexico. Taken together, the comparison between the study population, the FMC División del Norte, and the national population pyramid of Mexico highlights a clear demographic gradient: from a more heterogeneous age distribution at the national level to a progressively adult- and older adult–centred structure within clinical settings.

This age structure–centred demographic profile has direct epidemiological implications for the morbidity patterns observed in the present study. The representation of middle-aged and older adults within the study population creates a demographic context in which non-communicable diseases are expected to predominate. As age is one of the strongest determinants of cardiometabolic risk, populations with expanded adult and older adult cohorts consistently exhibit higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidaemia compared with younger populations [47-54]. Globally, non-communicable diseases are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality, accounting for slightly more than 70% of all deaths worldwide [48,55-57], with cardiovascular conditions, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes which are responsible for most premature deaths in adults aged 30–69 ld [58,59]. Evidence from cross-sectional studies across Latin America highlights hypertension and diabetes as the leading non-communicable diseases in adult populations. However, prevalence estimates demonstrate marked variability, with hypertension ranging from 9% to as high as 70%, and diabetes affecting approximately 8% to 9.8% of adults, underscoring the influence of demographic, socioeconomic, and healthcare access differences across the region [60-65].

In Mexico, national survey data further contextualise these findings. Recent population-based estimates indicate that diabetes affects approximately 8–13% of adults, while combined overweight and obesity prevalence remains high at around 75%, conditions that partly explain the burden of related comorbidities observed in our outpatient sample [66,67]. Thus, our findings align with the patterns reported in urban primary care settings in Mexico [26] and other similar populations, highlighting the cumulative impact of metabolic, behavioral, and environmental risk factors over the life course. Moreover, the sex-stratified analysis indicates subtle but meaningful differences in disease distribution, such as higher rates of hypothyroidism and chronic venous insufficiency in females, suggesting the need for targeted, sex-specific interventions [26]. Beyond these predominant NCDs, our data also reveals other conditions that contribute substantially to outpatient service demand. These findings underscore the multifactorial nature of morbidity in primary care populations and emphasize the importance of integrating musculoskeletal, metabolic, and endocrine health management into routine care [26]. However, it is equally important to consider how population structure influences susceptibility to communicable diseases, which remain a persistent public health concern and interact with chronic conditions to shape overall morbidity patterns. International evidence indicates that in primary care settings, acute respiratory infections, urinary tract infections, and skin and soft tissue infections are the most frequently managed communicable diseases [68-70].

These conditions consistently account for most infectious disease consultations, reflecting their clinical relevance at the first level of care. This dual epidemiological profile aligns with international and regional evidence and provides an essential framework for interpreting the patterns of service utilisation and disease prevalence observed in the present study [71-76]. In Mexican context, our findings show a similar pattern with others studies in primary care [26]. Consequently, the predominance of non-communicable, and communicable diseases observed in our results should be interpreted not merely as a reflection of individual-level risk, but as an expected outcome of the underlying population structure. This demographic conditioning of disease patterns provides a critical explanatory framework for understanding why cardiometabolic conditions and infectious illness dominate outpatient morbidity profiles in the present study and sets the stage for the subsequent analysis of service utilisation and sexand age-specific disease distributions.

A major strength of this study is its large sample size and the comprehensive stratification by age and sex, which allow for a detailed characterization of population-level demographic patterns. Cross-sectional studies like this are particularly valuable for describing disease burden and clinical heterogeneity, as well as for generating hypotheses for future longitudinal, mechanistic, and interventional research. Additionally, the study provides insight into sex-specific morbidity patterns and offers evidence that can inform the design of integrated care models and targeted health interventions. Despite these strengths, several limitations should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design may lead to underreporting or misclassification, particularly for communicable diseases or conditions that rely primarily on clinical diagnoses. Furthermore, the predominance of older adults in the sample may limit the generalizability of findings to younger populations, whose risk factor profiles and early-life exposures may differ. The observed burden of morbidity underscores the importance of preventive strategies, including vaccination campaigns (e.g., influenza and pneumococcal vaccines), enhanced infection surveillance, and early therapeutic interventions, particularly for older adults and individuals with multiple comorbidities. These measures may help reduce the incidence and severity of infectious complications in high-risk groups. Finally, the findings support policies aimed at improving access to preventive services and prioritizing resources toward populations with the highest cardiometabolic and infectious burden.

Overall, the findings of our study provide a comprehensive epidemiological profile that underscores the core burden of cardiometabolic multimorbidity in this population. This profile reflects the cumulative impact of metabolic dysfunction, behavioral factors, and environmental exposures over the life course. Stratification by age and sex highlights important differences in disease distribution. In women, higher rates of hypothyroidism, chronic venous insufficiency, and musculoskeletal disorders suggest sex-specific health needs that require tailored clinical attention. In men, the accumulation of metabolic diseases indicates the need for focused preventive strategies to mitigate vascular risk. In conclusion, our study supports the adoption of comprehensive, age- and sex-sensitive interventions. Early identification of multimorbidity patterns and targeted preventive actions addressing cardiometabolic and infectious risk factors may contribute to reducing disease burden, optimizing healthcare utilization, and improving clinical outcomes in this adult population.

The authors would like to thank Professor Susana Ortiz Vela, Master in translation, and also express their gratitude to the Centro de Investigación y de Educación Continua S.C. for their support in translation.

“Authors have declared that no competing interests exist.”.

All authors contributed to conceptualization (ideas, formulation, or development of research goals and objectives), formal analysis (application of statistical, mathematical, computational, or other formal techniques to analyse or synthesize study data), writing - original draft (preparation, creation, and/or presentation of the published work, specifically writing the initial draft), writing - review and editing (preparation, creation, and/or presentation of the published work by the research group, specifically critical review, commentary, or revisions, including pre- or post-publication stages), and visualization (preparation, creation, and/or presentation of the published work, specifically data visualization/presentation). López Hernández Daniel and Emmanuel Melgarejo Estefan, in addition to the above, contributed to project administration (responsibility for managing and coordinating the planning and execution of the research activity), investigation (development of a research process, specifically experiments or data collection/testing), methodology (development or design of methodology, creation of models), supervision (responsibility for supervision and leadership in the planning and execution of the research activity, including external mentoring), and validation (verification, whether as part of the activity or separately, of the overall replicability/reproducibility of the results/experiments and other research outcomes).

Authors hereby declare that NO generative AI technologies such as Large Language Models (ChatGPT, COPILOT, etc) and text-to-image generators have been used during writing or editing of manuscripts.

The study was conducted using medical records, and no informed consent was obtained. The handling of the information was approved by the ethics committee, ensuring compliance with the appropriate ethical standards.

The present study was conducted in compliance with the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, national regulations, and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects. To guarantee confidentiality, only the principal investigators had access to the complete dataset, including identifiable patient information (e.g., names). The patient names were replaced with unique identification numbers. The assigned number allows the data to be linked to a specific individual without revealing the individual’s identity. This approach ensured that all patient data were handled under ethical standards and maintained the highest level of confidentiality throughout the study. This anonymization was conducted before sharing the dataset for statistical analysis with some researchers. After the statistical analysis, only the processed statistical data were made available to the rest of the research team.