Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Daniel Lopez Hernandez1*, Leticia Brito Aranda2, Liliana Grisel Liceaga Perez3, Emmannuel Melgarejo Estefan4, Alberto Vazquez Sanchez5, Xochitl Liliana Olivares Lopez6, Victor Hugo Noguez Alvarez7, Maria Luisa Lucero Saldivar Gonzalez8, Aline Vanessa Carrera Vite3, Maria Clara Hernandez Almazan9, Abraham Espinoza Perdomo2 and Marcos Meneses Mayo10

Received: December 17, 2025; Published: December 22, 2025

*Corresponding author: Daniel Lopez Hernandez, Family Medicine Clinic Division del Norte, Institute of Social Security and Services for State Workers (ISSSTE), Mexico City, Mexico

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2025.64.010023

Background: Dyslipidaemia is a major cardiometabolic condition frequently managed in Mexican primary care.

Characterising its demographic and epidemiological profile, it is essential to inform prevention and integrated

care.

Methods: We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional, analytical study using a secondary dataset from

the Medical Financial Information System (SIMEF) at the “División del Norte” Family Medicine Clinic (ISSSTE),

Mexico City. Adults with a clinical diagnosis of dyslipidaemia who attended outpatient consultations between

January and December 2022 were included. Sociodemographic characteristics and ICD-10–coded comorbidities

were analysed using descriptive statistics and 95% confidence intervals.

Results: A total of 2,141 adults with dyslipidaemia were included, predominantly female (62.3%). Age distribution

showed 5.0% in early adulthood, 39.0% in midlife, and 56.0% in the elderly stage, with the largest groups

being 60–69 years old (31.8%), 50–59 years old (26.5%), and 70–79 years old (18.0%). The five most prevalent

comorbidities were hypertension (43.6%), type 2 diabetes (41.2%), obesity (30.1%), prediabetes (9.6%), and

chronic venous insufficiency (8.8%). Sex-based differences were observed: males had higher prevalence of

hypertension (48.1%) and type 2 diabetes (45.0%), whereas females showed significantly higher rates of

obesity (32.6%), chronic venous insufficiency (11.3%), and hypothyroidism (10.8%).

Conclusion: Adults with dyslipidaemia in Mexican primary care present a substantial cardiometabolic and

chronic disease burden, with marked age- and sex-specific patterns. These findings underscore the importance

of life-course, sex-sensitive, and multidisciplinary strategies to improve prevention and comprehensive

management of dyslipidaemia and its associated conditions.

Keywords: Dyslipidaemia; Morbidity; Primary Care

Abbreviations: LDL-C: Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; HDL-C: High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels; NCDs: Non-Communicable Diseases; FMC: Family Medicine Clinic; EA: Early Adulthood; ML: Midlife; EP: Elderly Population; SD: Standard Deviation; IQR: Interquartile Range; ANP: Acute Nasopharyngitis; AH: Asymptomatic Hyperuricaemia; UTIs: Urinary Tract Infections; NAFLD: Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Dyslipidaemia represents one of the leading modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease, a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide [1-5]. It is characterised by the increased plasma level of lipids in the blood—such as elevated total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and triglycerides, or reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels (HDL-C)—which contribute significantly to the development of atherosclerosis and its complications [1,3-5]. Dyslipidaemia affects a large proportion of the adult population, especially in the Western hemisphere [5], and is estimated to be responsible for 4.4 million deaths worldwide [1]. In the United States, approximately 53% of adults are affected by dyslipidaemia [1]. Similarly, in Canada, 45% of individuals aged 18–79 years old have dyslipidaemia, and 57% of them are unaware of their condition [6]. This underdiagnosis underscores the importance of population- based screening and preventive strategies aimed at early detection and management of lipid abnormalities to reduce cardiovascular risk globally. Its prevalence continues to increase due to population ageing, urbanisation, sedentary lifestyles, and unhealthy dietary patterns. Dyslipidaemia is increasingly recognised as a disease entity rather than merely a marker of cardiovascular or metabolic dysfunction. It encompasses a range of genetic and acquired disorders and frequently coexists with other non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and obesity, reflecting a shared underlying metabolic imbalance [7-9].

This clustering of metabolic risk factors amplifies the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, posing a substantial challenge to health systems—particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where access to screening and long-term management remains limited [10-12]. In Mexico, NCDs are the primary health public problem, with coronary heart disease and diabetes as the first and second causes of death, respectively, followed by stroke [13]. Likewise, between 40% and 66% of adults present hypercholesterolemia, around 50-60% have hypoalphalipoproteinemia, and between 30% and more than 50% exhibit hypertriglyceridemia [13-16]. Moreover, hypertension (Females: OR=3.0; 95% CI 1.7–5.3; males: OR=5.5; 95% CI 3.5–8.8) hypertriglyceridemia (Females: OR=2.3; 95% CI 1.2–4.5; males: OR=3.5; 95% CI 2.3–5.5) and the lipid triad (Females: OR=2.2; 95% CI 1.1–4.3; males: OR=3.2; 95% CI 2.0–5.1) were the main risks factors associated with myocardial infraction in a middle class urban Mexican population [17]. Therefore, the lipid triad has been proposed as a cardiovascular risk marker in the Mexican population [18]. Primary care plays a pivotal role in the detection, prevention, and management of dyslipidaemia. Primary care providers are often the first point of contact for patients at risk of lipid disorders, making them essential in early identification, counselling, pharmacological treatment, and follow-up of these kinds of patients [19-20].

As the frontline of healthcare delivery, primary care is uniquely positioned to implement lifestyle interventions, monitor therapeutic adherence, and coordinate multidisciplinary care aimed at reducing long-term cardiovascular risk [19-22]. From an epidemiological and governance standpoint, understanding the distribution and determinants of dyslipidaemia is essential for effective resource allocation, risk stratification, and policy planning [20-21,23]. Epidemiological characterisation of this condition within primary care enables the identification of vulnerable groups, the assessment of comorbidities, and the evaluation of current preventive strategies [20-21,23]. Furthermore, analysing the demographic, clinical, and social profiles of patients with dyslipidaemia supports the design of evidence-based interventions that integrate metabolic control, behavioural change, and health equity [20-21,23]. Therefore, characterising patients with dyslipidaemia in primary care is crucial for guiding targeted actions that improve both individual and population health outcomes. This approach contributes to the development of comprehensive, patient-centred care models and strengthens public health policies aimed at reducing the growing cardiovascular burden associated with lipid disorders. The aim of the study was to establish the sociodemographic, clinical characteristics, and epidemiological profile of the population with dyslipidaemia served in a primary care unit in Mexico City.

Study Design and Data Collection

The present study was designed as a population-based, cross-sectional, and analytical investigation using a previously published secondary dataset [24]. The data included patients from Mexico who were attended in outpatient consultations at the Family Medi-cine and General Medicine departments of the “División del Norte” Family Medicine Clinic (FMC), ISSSTE (Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado, by its acronym in Spanish), in Mexico City, Mexico [24]. The dataset was extracted from the Medical Financial Information System (SIMEF), which systematically records outpatient consultations conducted by healthcare personnel [24]. The dataset included medical records from January to December 2022 and was previously analyzed and published by our team work group [24]. The complete database is consisting of 73,974 records corresponding to 17,918 patients of all age groups [24]. For this study, an initial eligibility screening was performed to include only records corresponding to patients aged 20 years old and older (n = 16,197). A secondary inclusion criterion was then applied, restricting the analytical sample to individuals with a confirmed diagnosis of dyslipidaemia (n = 2,141). The study was conducted from August 1st to October 30th, 2025.

Patient Selection and Study Population

The Data Collection Procedure Included the Following Steps: 1. Data was extracted monthly (January–December) from Excel files generated by the SIMEF system.

2. A unified database was subsequently constructed, and all individual patient records were cross-referenced to verify internal consistency and minimise duplication.

3. A final validation step was performed to ensure the integrity and completeness of the merged dataset.

4. The consolidated database was then screened to identify records meeting the study’s inclusion criteria, while those not fulfilling these criteria were excluded.

5. Following this eligibility assessment, a total of 2,141 individuals aged 20 years old and older with a confirmed diagnosis of dyslipidaemia, ensuring the accuracy, reliability, and quality of the final analytical sample.

6. All cleaned and validated data was stored in an Excel workbook, which served as the statistical dataset for subsequent epidemiological analyses.

Inclusion Criteria:

1. Patients with dyslipidaemia of both sexes aged 20 years old or older.

2. Individuals with at least one consultation registered in the SIMEF system during the study period.

3. Complete clinical records, including identification variables (name, file number, sex, beneficiary type), International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) diagnosis code(s), and consultation dates.

Exclusion Criteria:

1. Patients younger than 20 years old.

2. Records that were incomplete, inconsistent, or lacked essential identification or diagnostic information in the SIMEF system.

3. Duplicate records identified during data cleaning. Finally, a census sampling method was employed, including all eligible records from the newly generated dataset. All this ensured that only patients with complete and consistent records were included in the study.

Variables and Statistical Analysis

The variables analysed comprised age (in years), sex (male and female), number of outpatient consultations, and comorbidities coded according to the ICD-10. In total, 969 ICD-10 codes were registered. Three new variables were generated to identify obesity, dyslipidaemia, and age groups. For obesity, the following ICD-10 codes were included: E66.0 –Obesity; E66.8 –Other obesity; and E66.9 –Obesity, unspecified. For dyslipidaemia, the selected codes were: E78.0 –Pure hypercholesterolaemia; E78.1 –Pure hyperglyceridaemia; E78.2 – Mixed hyperlipidaemia; E78.4 –Other hyperlipidaemia; and E78.5 –Hyperlipidaemia, unspecified. For the age group variable, the population was categorised into three main age groups of interest: early adulthood (EA), midlife (ML), and the elderly population (EP). Categorical variables are presented as absolute frequencies and percentages, while quantitative variables are described using mean, standard deviation (SD), range, maximum value, minimum value, median, and interquartile range (IQR). A 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was reported where applicable. Comparisons of categorical variables were performed using the likelihood ratio and the Yates’ continuity correction chi-square (χ²) (LRχ² and Yχ², respectively) or Fisher´s exact test, as appropriate. Quantitative variables were compared using Student’s t-test, and Median Test between independent groups. A two-tailed p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

The present study was conducted in compliance with the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, national regulations, and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects. The study protocol received approval from two institutional bodies: the Research Committee and the Research Ethics Committee (approval number MFDN/SM//EZ/315/2024, dated February 6th 2024) of the FMC “División del Norte.”. The Data was treated confidentially. To guarantee confidentiality, only the principal investigators had access to the complete dataset, including identifiable patient information (e.g., names). The patient names were replaced with unique identification numbers. The assigned number allows the data to be linked to a specific individual without revealing the individual’s identity. This approach ensured that all patient data were handled under ethical standards and maintained the highest level of confidentiality throughout the study. This anonymization was conducted before sharing the dataset for statistical analysis with some researchers. After the statistical analysis, only the processed statistical data was made available to the rest of the research team.

Characteristics of the Study Population

A total of 2,141 patients with dyslipidaemia were included (pure hypercholesterolaemia; 246 cases; 11.5%; 95% CI 10.1–12.9; pure hyperglyceridaemia; 387 cases; 18.1%; 95% CI 16.4–19.8; mixed hyperlipidaemia; 650 cases; 30.4%; 95% CI 28.5–32.2; other hyperlipidaemia; 39 cases; 1.8%; 95% CI 1.3–2.4; and hyperlipidaemia, unspecified; 1326 cases; 61.9%; 95% CI 59.9–63.9). The average age, in overall population, was 60.74 (Figure 1) years old (SD=12.24, range=75, minimum age=21, maximum age=96 years old, median age=61 [IQR=53-69]). The average age in the patients with pure hypercholesterolaemia was 61.76 years old (SD=11.50, range=58, minimum= 29, maximum=87 years, median=63 [IQR=54–69]). Among patients with pure hyperglyceridaemia, the average age was 58.34 years old (SD=12.40), ranging from 23 to 91 years. The IQR extended from 50.0 to 67.0 years, with a median age of 58.0 years old. Likewise, the average age among patients with mixed dyslipidaemia was 60.10 yearsold (SD=11.92, range=66, minimum=23, maximum=89 years old, median=61 [IQR=52–68]). In addition, the average age of the patients between sexes was similar (males=61.2 versus females=60.5; p=0.109, using U Mann-Whitney test). Moreover, the median age was also similar in male patients (62 years old; IQR= 53-70) compared to female patients (61 years old; IQR=53-69; p=0.097, Median Test between independent groups).

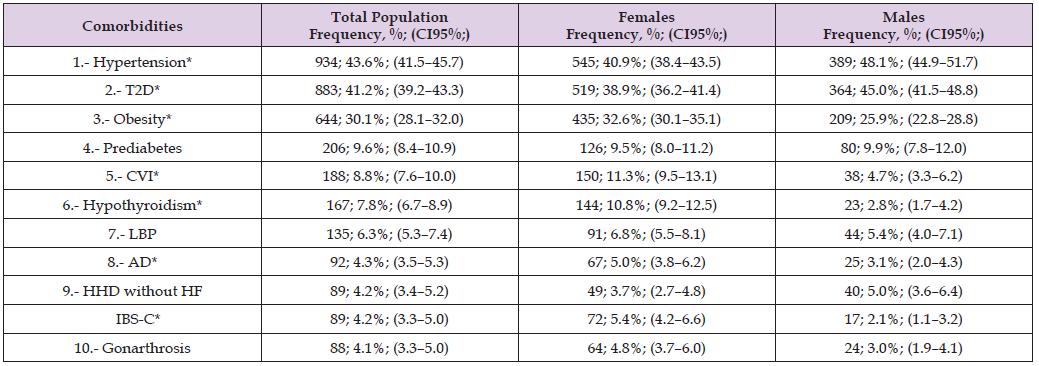

Table 1 presents the age distribution of the study population by sex and age group, providing an overview of the demographic structure of the population. Females represented many of the participants. The predominance of older adults reflects the demographic transition and the increasing ageing of the population, which has implications for the burden of chronic and degenerative diseases. Most participants were concentrated in the elderly group, particularly those aged 60–69 years old, followed by individuals in midlife, whereas young adults constituted a smaller segment of the study population. The sexbased distribution shows that females were more represented during the midlife decades, while males were proportionally more frequent among the oldest participants. Thus, this pattern underscores the importance of integrating sex- and age-specific approaches in preventive and healthcare strategies for the management of chronic diseases. Table 2 summarises the epidemiological distribution of the ten most prevalent non-communicable diseases (NCDs) identified among patients with dyslipidaemia, including a sex-based comparison. The results highlight a high burden of cardiometabolic comorbidities within this population, consistent with the known clustering of metabolic risk factors. Hypertension and type 2 diabetes were the two most frequent conditions, both showing a significantly higher prevalence among males, which reflects the strong metabolic and vascular associations commonly observed in patients with dyslipidaemia.

Note: Source: Prepared by the authors using the resulte from the SIMEF database, January-December, 2022. EA: early adulthood (20-39 years old). ML: midlife (40-59 years old). EP: elderly population (60 years old and over). Decades: 20-29 years old; 30-39 years old; 40-49 years old; 50-59 years old; 60-69 years old; 70-79 years old; 80-89 years old; 90-99 years old. Comparisons among age group and sex were performed using the Likelihood Ratio chi-square (LRχ² = 10.395, df = 2, p = 0.006). Comparisons among age decades and sex were performed using the Likelihood Ratio chi-square (LRχ² = 17.201, df = 7, p = 0.016).

Table 2: Epidemiological distribution and sex-based comparison of the ten most prevalent non-communicable diseases in the study population.

Note: Source: Prepared by the authors using the results from the SIMEF database, January-December, 2022. T2D: type 2 diabetes. CVI: chronic venous insufficiency. LBP: low back pain. AD: anxiety disorder. HHD without HF: hypertensive heart disease without heart failure. IBS-C: irritable bowel syndrome, constipation-predominant. Comparisons between sex were performed using the Yates’ continuity correction chi-square (Yχ²); degree freedom (df). *P values statistically significative. *Hypertension (Yχ²=10.777, df=1, p=0.001); *type 2 diabetes (Yχ²=7.762, df=1, p=0.005); *obesity (Yχ²=10.953, df=1, p=0.001); prediabetes (Yχ²=0.116, df=1, p=0.733); CVI* (Yχ²=26.944, df=1, p<0.001); hypothyroidism* (Yχ²=44.279, df=1, p<0.001); low back pain (Yχ²=1.624, df=1, p=0.202); anxiety disorder* (Yχ²=4.567, df=1, p=0.033); HHD without HF (Yχ²=2.051, df=1, p=0.152); IBS-C* (Yχ²=13.729, df=1, p<0.001); and gonarthrosis (Yχ²=4.279, df=1, p=0.039).

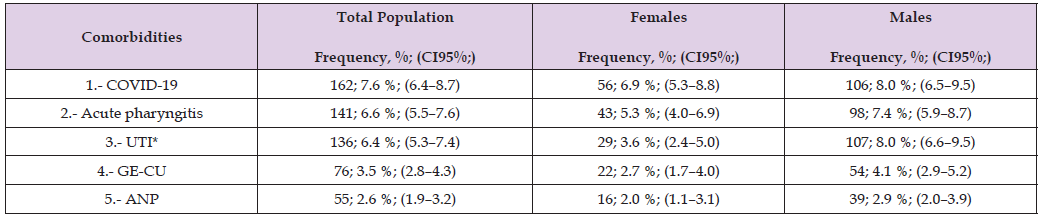

Obesity ranked third in overall frequency and was more prevalent among females, indicating an important sex difference in metabolic risk patterns. The coexistence of obesity and dyslipidaemia reinforces the role of excess adiposity as a key driver of insulin resistance, low-grade systemic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction, all of which contribute to the progression of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Other relevant comorbidities included prediabetes, chronic venous insufficiency, hypothyroidism, and low back pain. Chronic venous insufficiency and hypothyroidism were notably more prevalent among females, while hypertensive heart disease without heart failure and low back pain showed no significant sex differences. Anxiety disorder and irritable bowel syndrome (constipation-predominant) were also more frequent in females, suggesting an interaction between metabolic, hormonal, and psychosomatic factors. The coexistence of these conditions underscores the complexity of managing dyslipidaemia in primary care. The high prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity illustrates the need for integrated, multidisciplinary strategies focused on early detection, weight control, behavioural interventions, and long-term cardiovascular risk reduction tailored to both sexes. Table 3 presents the epidemiological distribution of the five most prevalent communicable diseases identified among patients with dyslipidaemia, along with a comparison by sex.

Table 3: Epidemiological distribution and sex-based comparison of the five most prevalent communicable diseases in the study population.

Note: Source: Prepared by the authors using the results from the SIMEF database, January-December, 2022. UTI: urinary tract infection. GE-CU: gastroenteritis and colitis of unspecified origin. ANP: acute nasopharyngitis [common cold]. Comparisons between sex were performed using the Yates’ continuity correction chi-square (Yχ²); degree freedom (df). *P values statistically significative. COVID-19, virus identified (Yχ²=0.750, df=1, p=0.386); acute pharyngitis (Yχ²=3.370, df=1, p=0.066); *urinary tract infection (Yχ²=16.656, df=1, p<0.001); gastroenteritis and colitis of unspecified origin (Yχ²=2.592, df=1, p=0.107); and acute nasopharyngitis [common cold] (Yχ²=1.797, df=1, p=0.180).

Understanding the coexistence of infectious diseases within this population is essential, as mounting evidence indicates a bidirectional relationship between communicable and NCDs, particularly through shared mechanisms of inflammation, immune dysfunction, and metabolic alteration. Among the studied conditions, COVID-19 was the most frequent communicable disease, followed by acute pharyngitis and urinary tract infections (UTI). On the other hand, the notable prevalence of COVID-19 in this group underscores the vulnerability of patients with dyslipidaemia to infectious diseases, given their increased risk of severe outcomes associated with metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities. Acute pharyngitis also showed a moderate frequency, reflecting the persistence of upper respiratory tract infections in adults, while UTIs were significantly more prevalent among males in this cohort—an atypical finding that may relate to the age distribution and higher frequency of comorbid conditions such as diabetes and prostatic disease. Gastroenteritis and colitis of unspecified origin (GE-CU) and acute nasopharyngitis (ANP) were less frequent but still relevant within the overall infectious profile. Therefore, these conditions illustrate the ongoing burden of gastrointestinal and respiratory infections, which can exacerbate metabolic instability and contribute to inflammatory processes that worsen lipid profiles and vascular health. These findings highlight the importance of integrated surveillance and management of both communicable and NCDs in patients with dyslipidaemia.

Strengthening infection prevention, vaccination, and timely treatment— especially in individuals with metabolic disorders—may reduce complications and improve overall health outcomes in this highrisk population.

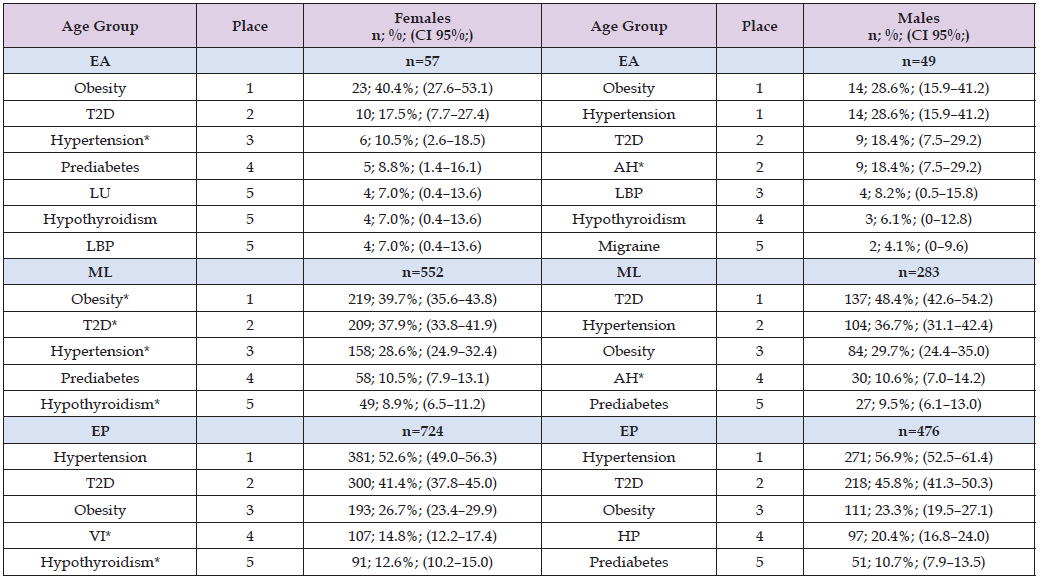

Age- and Sex-Specific Epidemiological Profiles of Non-Communicable Diseases in Patients with Dyslipidaemia

Across our study population, a clear and consistent epidemiological profile emerged: diabetes, hypertension, and obesity were the three most prevalent comorbidities in both sexes and across all age groups. These conditions form the core of a shared cardiometabolic multimorbidity profile, highlighting a substantial burden of non-communicable disease that persists throughout the life course. Among EA and ML females, the ordering of the three principal comorbidities was uniform—obesity ranked first, followed by diabetes and hypertension. In all female age groups, diabetes consistently occupied the second position, suggesting an early and sustained presence of dysglycaemia in women with dyslipidaemia. Besides, in older women, hypertension became the most frequent comorbidity, while obesity declined to third place, suggesting an age-related shift in metabolic and vascular risk. Notably, hypothyroidism ranked fifth in all female age strata, indicating a stable pattern of thyroid dysfunction across the lifespan. The fourth-ranked condition differed by age: prediabetes in younger and midlife women, and peripheral venous insufficiency in older women. Additionally, leiomyoma of uterus and low back pain occupying the lower positions among young females joint to hypothyroidism (Table 4). In young males, obesity and hypertension jointly occupied the first position, followed by diabetes and asymptomatic hyperuricaemia in second place, and then low back pain, hypothyroidism, and migraine in the subsequent ranks.

Table 4: Comparison of age and sex-specific epidemiological profiles of non-communicable diseases in the Study Population.

Note: Source: Prepared by the authors using the results from the SIMEF database, January-December, 2022. EA: early adulthood. ML: midlife. EP: elderly population. T2D: type 2 diabetes. LU: leiomyoma of uterus. LBP: low back pain. VI: venous insufficiency (chronic)(peripheral). AH: asymptomatic hyperuricaemia (hyperuricaemia without signs of inflammatory arthritis and tophaceous disease). HP: hyperplasia of prostate. Comparisons between sex were performed using the Yates’ continuity correction chi-square (Yχ²), and Fisher exact test, as appropriate; degree freedom (df). *P values statistically significative. Obesity (EA: Yχ²=1.132; df=1; p=0.287; *ML: Yχ²=7.653; df=1; p=0.006; EP: Yχ²=1.520; df=1; p=0.218); T2D (EA: Yχ²=0.0; df=1; p=1.0; *ML: Yχ²=8.148; df=1; p=0.004; EP: Yχ²=2.053; df=1; p=0.152); hypertension (*EA: Yχ²=4.488; df=1; p=0.034; *ML: Yχ²=5.366; df=1; p=0.021; EP: Yχ²=1.978; df=1; p=0.160); prediabetes (EA: Fisher exact test; p=0.447; ML: Yχ²=0.100; df=1; p=0.752; EP: Yχ²=1.129; df=1; p=0.288); hypothyroidism (EA: Fisher exact test; p=1.000; *ML: Yχ²=11.258; df=1; p=0.001; *EP: Yχ²=33.883; df=1; p<0.001); low back pain (EA: Fisher exact test; p=1.000; ML: Yχ²=0.756; df=1; p=0.385; EP: Yχ²=0.833; df=1; p=0.361); venous insufficiency (EA: Fisher exact test; p=0.498; ML: Yχ²=2.037; df=1; p=0.153; *EP: Yχ²=25.660; df=1; p<0.001); asymptomatic hyperuricaemia (*EA: Fisher exact test; p=0.001; *ML: Yχ²=33.994; df=1; p<0.001; *EP: Yχ²=16.748; df=1; p<0.001); migraine (EA: Fisher exact test; p=0.595; *ML: Fisher exact test; p=0.032; EP: Fisher exact test; p=0.710).

Among midlife males, the order followed a classic cardiometabolic pattern: diabetes first, hypertension second, obesity third, followed by asymptomatic hyperuricaemia and prediabete. Also, in older males, the sequence was similarly aligned with chronic metabolic risk: hypertension ranked first, diabetes second, obesity third, followed by prostatic disease and prediabetes (Table 4). Moreover, in EA, males exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of hypertension and asymptomatic hyperuricaemia (AH) compared with females (Table 4). In ML, several sex-specific differences emerged: obesity, hypothyroidism and migraine were significantly more common in females, whereas males showed higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and AH. Among older adults, hypothyroidism and venous insufficiency were significantly more prevalent in females, while AH continued to be more common in males. Taken together, these findings reflect robust and biologically plausible epidemiological trends. They underscore the dominant role of lifelong cardiometabolic risk, the early emergence of metabolic dysfunction in both sexes, and the added contribution of sex-specific and age-dependent conditions—such as uterine leiomyomas in females and prostate disease in males—as individuals age. Therefore, the consistency of the three leading comorbidities emphasises the need for integrated cardiovascular risk-reduction strategies across the life course, while the age- and sex-specific variations highlight the importance of tailored, population-specific clinical and public-health interventions.

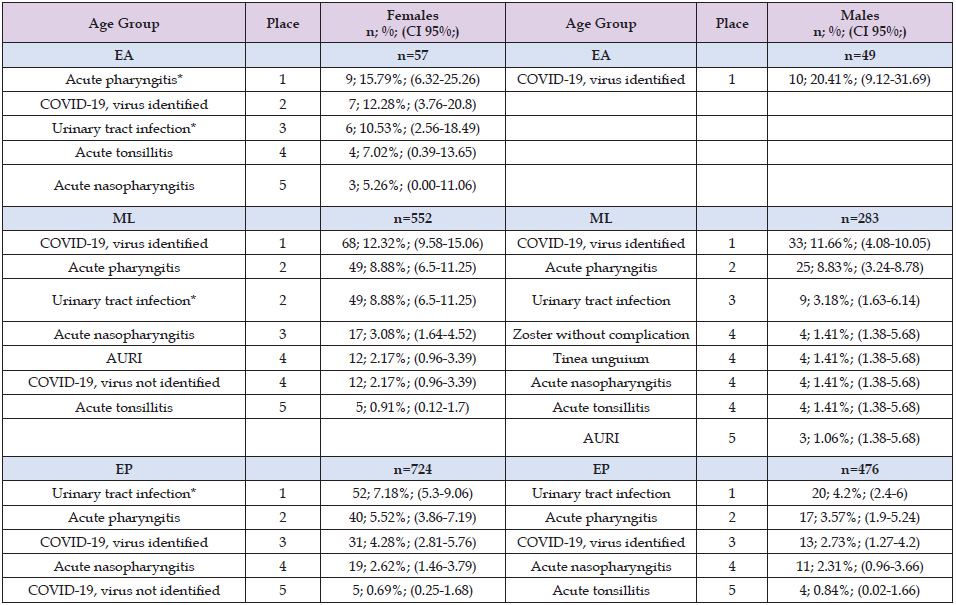

Age- and Sex-Specific Epidemiological Profiles of Communicable Diseases in Patients with Dyslipidaemia

When we analyzed communicable diseases across all age groups, respiratory infections were the most prevalent communicable diseases among patients with dyslipidaemia, consistently surpassing other infectious conditions in both females and males. This pattern highlights a sustained vulnerability of patients with dyslipidaemia to acute respiratory pathogens throughout the life course, with conditions such as acute pharyngitis, acute nasopharyngitis, acute tonsillitis and COVID-19 accounting for the majority of infectious morbidity, while other infections, including urinary tract infections, showed a comparatively lower and more age-restricted frequency (Table 5). Among EA, females were more frequently affected by acute upper respiratory infections, with acute pharyngitis being the leading condition, followed by laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, whereas males showed a marked predominance of confirmed COVID-19. In the ML group, confirmed COVID-19 remained the most prevalent condition in both females and males, accompanied by substantial burdens of acute pharyngitis and urinary tract infections (UTIs), with a consistently higher prevalence of UTIs in females compared with males; males in this group also presented a broader spectrum of infectious conditions, including herpes zoster without complications and tinea unguium.

Table 5: Comparison of age and sex-specific epidemiological profiles of communicable diseases in the Study Population.

Note: Source: Prepared by the authors using the results from the SIMEF database, January-December, 2022. EA: early adulthood. ML: midlife. EP: elderly population. AURI: acute upper respiratory infection. Comparisons between sex were performed using the Yates’ continuity correction chi-square (Yχ²), and Fisher exact test, as appropriate; degree freedom (df). *P values statistically significative. B02.9; zoster without complication (EA: not determined due to the absence of reported cases; ML: Fisher´s exact test; p=0.236; EP: Fisher´s exact test; p=0.062); B35.1; tinea unguium (EA: not determined due to the absence of reported cases; ML: Fisher´ss exact test; p=0.188; EP: Fisher´s exact test; p=0.542); J00.X; acute nasopharyngitis (EA: Fisher´s exact test; p=0.622; ML: Fisher´s exact test; p=0.168; EP: Yχ²=0.023; df=1; p=0.880); J02.9; acute pharyngitis (*EA: Fisher´s exact test; p=0.019; ML: Yχ²=0.000; df=1; p=1.000; EP: Yχ²=2.010; df=1; p=0.156); J03.9; acute tonsillitis (EA: Fisher´s exact test; p=0.370; ML: Fisher´s exact test; p=0.497; EP: Fisher´s exact test; p=0.720); J06.9; acute upper respiratory infection, unspecified (EA: Fisher´s exact test; p=1.000; ML: Fisher´s exact test; p=0.800; EP: Fisher´s exact test; p=0.710); N39.0; urinary tract infection, site not specified (*EA: Fisher´s exact test; p=0.029; *ML: Yχ²=8.532; df=1; p=0.003; *EP: Yχ²=4.011; df=1; p=0.045); U07.1; COVID-19, virus identified (EA: Yχ²=0.759; df=1; p=0.384; ML: Yχ²=0.027; df=1; p=0.870; EP: Yχ²=1.541; df=1; p=0.215); U07.2; COVID-19, virus not identified (EA: Fisher´s exact test; p=1.000; ML: Fisher´s exact test; p=0.409; EP: Fisher´s exact test; p=1.000).

Furthermore, in the EP, the epidemiological profile shifted towards the predominance of urinary tract infections as the leading communicable disease in both sexes, followed by respiratory infections such as acute pharyngitis and COVID-19. Our findings indicate that females consistently showed a proportionally higher overall prevalence of UTIs, whereas males had a comparatively greater prevalence of viral respiratory illnesses, particularly in younger age groups.

Discussion

The present study describes a large sample of 2,141 patients with dyslipidaemia, whose demographic and clinical characteristics confirm a population with a high cardiometabolic burden. The predominance of older adults (median age 61 years old) and female participants reflects the demographic transition and the growing burden of chronic metabolic disorders in our setting. The distribution of dyslipidaemia phenotypes — including pure hypercholesterolaemia, pure hyperglyceridaemia, mixed and unspecified hyperlipidaemia — is broadly diverges with global estimates [24]. In our cohort, we observed a high proportion of mixed and (≈ 30.4 % mixed), and only 11.5 % of patients had pure hypercholesterolaemia — a pattern that diverges somewhat from the classical view of hypercholesterolaemia as the predominant dyslipidaemic phenotype [24]. According to a recent global meta-analysis of adult populations, the pooled prevalence of hypercholesterolaemia was 24.1 %, and 18.9% for high LDL-C [25], while hypertriglyceridaemia (28.8%) was more prevalent compared with our findings (18%), which increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and pancreatitis [25-26]. This meta-analysis also highlights an epidemiological shift: whereas hypercholesterolaemia remains common, there has been a relative increase over recent decades in hypertriglyceridaemia especially in regions such as Latin America and North America [25]. However, the prevalence of hypertriglyceridaemia varies widely across world regions, with both higher and lower rates than those observed in our study population.

The highest prevalences have been reported in Lithuania (56.71%), Palau (44.37%), South Africa (43.68%), and the Middle East (32.5%), whereas the lowest have been documented in Benin (2.03%), Brazil (7.79%), and China (8.20%) [25,27]. In addition, the prevalence of hypercholesterolaemia observed in our study population (approximately 11%) is higher than the prevalences reported in Australia (6.91%), Japan (8.22%), and Lithuania (9.55%), but substantially lower than those reported in Pakistan (79.81%), Venezuela (70.73%), Saudi Arabia (69.45%), and the Middle East (29.4%) [25,27]. This wide geographical heterogeneity highlights the influence of genetic, dietary, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors on triglyceride levels across populations. On the other hand, our data shows that hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and obesity are the most frequent comorbidities across sexes and age groups. This aligns with previous findings in Mexican urban populations, in which the clustering of metabolic risk factors (lipid triad, obesity, hypertension) represents the main attributable risk for atherosclerotic events [17- 18,28-29]. Notably, in midlife women obesity appeared as the most prevalent risk factor, whereas in older age hypertension overtook — suggesting an age-related shift from adiposity-driven risk to vascular risk. These trends support the need for continuous, metabolic, and cardiovascular life-course risk assessment and interventions.

Likewise, in middle-aged Indian population, evidence indicates that individuals classified with pre-obesity and obesity carry a substantially higher burden of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and dyslipidaemia, also reflecting a pattern of cardiometabolic risk clustering at the population level [30]. Besides, our findings show a comparable epidemiological profile, as middle-aged patients with dyslipidaemia exhibited a high prevalence of diabetes, hypertension and obesity in both females and males. In addition, in our female middle-aged group, prediabetes and hypothyroidism also represented important comorbidities, whereas in males, prediabetes and asymptomatic hyperuricaemia were additionally observed, suggesting sex-specific variations in metabolic risk profiles. From a public health perspective, the additional burden of prediabetes and hypothyroidism among middle- aged women, and of prediabetes and asymptomatic hyperuricaemia among men, highlights the need for sex-specific screening, early metabolic risk detection and targeted prevention strategies aimed at reducing the long-term burden of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. This coexistence of dyslipidaemia and thyroid dysfunction observed in our population is epidemiologically relevant and supported by a growing body of evidence [31-33]. Subclinical hypothyroidism is now recognised as atherogenic condition, as they promote adverse lipid profiles and are associated with diastolic dysfunction, ischaemic heart disease, heart failure and increased all-cause mortality [31].

Thyroid hormones play a central role in lipid homeostasis through both transcriptional and non-transcriptional mechanisms, regulating the synthesis and clearance of LDL, HDL, VLDL and triglycerides [32]. Consequently, hypothyroidism tends to exacerbate hypercholesterolaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia, whereas hyperthyroidism may reduce circulating cholesterol and mask underlying dyslipidaemia [32]. From a public health perspective, this bidirectional relationship supports the routine biochemical screening for thyroid dysfunction in patients with dyslipidaemia and, inversely, the evaluation of lipid abnormalities in individuals with thyroid disease. In addition, hypothyroidism- associated dyslipidaemia has been linked to intrahepatic fat accumulation and the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which contributes to hepatic insulin resistance and further amplifies cardiometabolic risk [33]. Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that selective thyroid hormone receptor-β agonists may represent promising therapeutic strategies for dyslipidaemia and NAFLD [33]. Collectively, these findings reinforce the importance of integrated metabolic and endocrine screening strategies aimed at reducing the long-term burden of cardiovascular and liver disease in populations with dyslipidaemia. Regarding communicable diseases, our analysis reveals that respiratory infections (including acute pharyngitis, nasopharyngitis, tonsillitis, and confirmed COVID‑19) dominate the infectious morbidity profile in patients with dyslipidaemia.

This was true across all age groups and both sexes, consistent with a sustained vulnerability to acute respiratory pathogens throughout life. Meanwhile, UTIs — while present — has a comparatively lower and more age- and sex-restricted frequency. This pattern might be partially explained by age-dependent changes in immune competence, anatomical factors, and comorbid conditions (e.g. diabetes, prostate disease), but also suggests that metabolic disorders per se may predispose preferentially to respiratory rather than urinary infections in this population [34-37]. Interestingly, the predominance of cardiometabolic NCDs combined with frequent respiratory infections may reflect a bidirectional interaction: dyslipidaemia (especially when accompanied by obesity, hypertension, and diabetes) fosters an inflammatory milieu and immune dysregulation that can increase susceptibility to infections; conversely, recurrent, or chronic infections may exacerbate metabolic and vascular dysregulation, accelerating atherogenesis. This interplay could contribute to the excess cardiovascular risk observed in patients with dyslipidaemia. Indeed, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and other lipid abnormalities have been recently associated with susceptibility to bacterial and viral infections in large population studies [38], suggesting that lipid profile per se may modulate immune defence. Furthermore, the coexistence of NCDs and communicable diseases in this dyslipidaemic cohort underscores the complexity of managing these patients in primary care.

It calls for integrated strategies that combine cardiovascular risk reduction (through lifestyle modification, lipid control, weight management) with strengthened infection prevention (e.g. immunisation, respiratory hygiene) — particularly in older adults and those with multiple comorbidities. Finally, our findings reinforce that in Mexican population, traditional cardiovascular risk scores may underestimate risk because they often exclude hypertriglyceridaemia and other dyslipidaemic traits prevalent in our population. Therefore, a tailored risk assessment tool that incorporates specific metabolic and demographic characteristics — including lipid triad, obesity, and comorbidities — seems justified to improve preventive accuracy and guide more effective interventions.

Limitations and Applications

A major strength of this study is its large sample size and the comprehensive stratification by age and sex, which together allow a robust characterization of epidemiological patterns across the life course. This level of granularity enhances the ability to identify sex-specific phenotypes, age-related multimorbidity clusters, and comorbid conditions that frequently accompany dyslipidemia. Methodologically, cross-sectional studies such as this one are particularly valuable for population characterization, providing an overview of disease burden, risk factor distribution, and clinical heterogeneity. They enable the identification of disparities in metabolic, cardiovascular, and inflammatory profiles that may differ substantially between men and women. These insights support the development of hypothesis-generating evidence for future longitudinal, mechanistic, and interventional studies. Additionally, the study contributes to a clearer understanding of the multimorbidity patterns associated with dyslipidemia, offering essential baseline data for monitoring trends over time and for informing surveillance systems. Clinically, its findings highlight subgroups with elevated risk—such as older adults and individuals with multiple cardiometabolic conditions—who may benefit from intensified screening, personalized risk assessment, and targeted management. Likewise, the results provide evidence to support the design of integrated care models, resource planning, and health system prioritization.

The identification of high-burden comorbidity profiles can guide the development of risk-stratified prevention programs, improve the targeting of vaccination or disease-prevention campaigns, and justify the allocation of resources toward populations with the highest need. Despite its strengths, several limitations must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design captures information at a single point in time, which prevents establishing temporal order or causal relationships between dyslipidemia and associated comorbidities. This design inherently restricts the ability to infer disease progression or the directionality of associations. Moreover, potential underreporting or misclassification may occur, particularly for communicable diseases or conditions that rely on clinical diagnosis rather than comprehensive laboratory confirmation. Variability in diagnostic practices, access to healthcare, and reporting quality across subgroups may also affect the accuracy and consistency of the data. The predominance of older adults in the sample could limit the generalizability of findings to younger populations, whose risk factor profiles and early-life exposure patterns may differ. Furthermore, clinical heterogeneity, socioeconomic disparities, and unequal access to preventive care may introduce biases that reduce the general applicability of the findings to other settings or populations. The study’s findings underscore the need for integrated clinical approaches that address not only lipid control but also the broader constellation of cardiometabolic and infectious risks.

Clinicians should incorporate both metabolic and infectious risk factors into patient assessments, and refine risk prediction tools to reflect the patterns observed in Mexican and Latin American populations— where dyslipidemia frequently coexists with obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and chronic inflammation. Furthermore, the high burden of multimorbidity reinforces the importance of preventive strategies, including vaccination campaigns (e.g., influenza and pneumococcal vaccines), improved infection surveillance, and early treatment interventions, especially for older adults and individuals with multiple comorbidities. These strategies may reduce the incidence and severity of infectious complications in high-risk groups. Also, the data provide a valuable reference for trend monitoring, the identification of vulnerable subpopulations, and the design of risk-based health promotion programs. Finally, the findings support policy initiatives aimed at strengthening integrated chronic disease management, improving access to preventive services, and prioritizing resource allocation toward populations with the highest cardiometabolic and infectious burden.

Overall, the findings of this study reveal robust epidemiological patterns consistent with the known pathophysiology of dyslipidemia and its associated comorbidities. The predominant burden of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity—present in both sexes and across all stages of life—confirms the existence of a core cluster of cardiometabolic multimorbidity that persistently accompanies patients with dyslipidemia. This profile not only reflects the coexistence of traditional risk factors but also highlights the synergistic interaction among metabolic dysfunction, chronic inflammation, and vascular impairment. The stratification by age and sex also shows relevant epidemiological differences. In women, the early and sustained presence of dysglycemia, the higher prevalence of obesity during the initial life stages, and the increased frequency of hypertension in older ages suggest metabolic transitions that are specific to female aging. The stable pattern of hypothyroidism across all ages further reinforces its role as a meaningful endocrinological determinant in this group.in contrast, in men, the predominance of diabetes and hypertension in middle and older age, along with the high prevalence of asymptomatic hyperuricemia, suggests a greater and potentially more accelerated accumulation of vascular risk. Among older adults, the high frequency of venous insufficiency in women and prostatic disease in men underscores the need for clinical approaches that account for biological and sex-specific differences.

These findings also emphasize the importance of early intervention, especially in younger individuals, in whom key metabolic comorbidities are already evident. In conclusion, the results highlight the urgent need to adopt comprehensive, preventive, and personalized strategies in the management of dyslipidemia, incorporating both age and sex perspectives. Thus, early identification of multimorbidity patterns and intensive intervention on cardiometabolic risk factors may significantly contribute to reducing disease burden and improving clinical outcomes in this population.

The authors would like to thank Professor Susana Ortiz Vela, Master in translation, and also express their gratitude to the Centro de Investigación y de Educación Continua S.C. for their support in translation.

“Authors have declared that no competing interests exist.”.

All authors contributed to conceptualization (ideas, formulation, or development of research goals and objectives), formal analysis (application of statistical, mathematical, computational, or other formal techniques to analyse or synthesize study data), writing - original draft (preparation, creation, and/or presentation of the published work, specifically writing the initial draft), writing - review and editing (preparation, creation, and/or presentation of the published work by the research group, specifically critical review, commentary, or revisions, including pre- or post-publication stages), and visualization (preparation, creation, and/or presentation of the published work, specifically data visualization/presentation). López Hernández Daniel, in addition to the above, contributed to project administration (responsibility for managing and coordinating the planning and execution of the research activity), investigation (development of a research process, specifically experiments or data collection/testing), methodology (development or design of methodology, creation of models), supervision (responsibility for supervision and leadership in the planning and execution of the research activity, including external mentoring), and validation (verification, whether as part of the activity or separately, of the overall replicability/reproducibility of the results/experiments and other research outcomes).

Authors hereby declare that NO generative AI technologies such as Large Language Models (ChatGPT, COPILOT, etc) and text-to-image generators have been used during writing or editing of manuscripts.

The study was conducted using medical records, and no informed consent was obtained. The handling of the information was approved by the ethics committee, ensuring compliance with the appropriate ethical standards.

The present study was conducted in compliance with the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, national regulations, and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects. The study protocol received approval from two institutional bodies: the Research Committee and the Research Ethics Committee (approval number MFDN/SM//EZ/315/2024, dated 6 February 2024) of the FMC “División del Norte.”. The Data was treated confidentially. To guarantee confidentiality, only the principal investigators had access to the complete dataset, including identifiable patient information (e.g., names). The patient names were replaced with unique identification numbers. The assigned number allows the data to be linked to a specific individual without revealing the individual’s identity. This approach ensured that all patient data were handled under ethical standards and maintained the highest level of confidentiality throughout the study. This anonymization was conducted before sharing the dataset for statistical analysis with some researchers. After the statistical analysis, only the processed statistical data were made available to the rest of the research team.