Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Shaima Ibrahim1, Omnia Abdulrahim1, Wafa Abuelkheir Mataria1 and Sungsoo Chun2*

Received: October 16, 2025; Published: October 24, 2025

*Corresponding author: Sungsoo Chun, Institute of Global Health and Human Ecology, The American University in Cairo, Office #: 2118, AUC Avenue, P.O. Box 74, New Cairo 11835, Egypt

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2025.63.009925

Background: Marked by high mortality rates on a global scale, with disease mortality being notably focused

among older adults, the COVID-19 pandemic has become a significant health crisis. Despite the numerous publications

on COVID-19 mortality among older adults, there is still a gap in knowledge when considering centenarians,

as there is no systematic review and meta-analysis that summarizes COVID-19 mortality in centenarians

globally.

Objective: This study aims to systematically review and synthesize global evidence on COVID-19 mortality rates

among centenarians and the population of older adults worldwide, whether residing in long-term health facilities,

hospitals, or their homes.

Methods: An automated search was conducted on the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science.

Observational studies, both cohort and case-control, were selected. Quality assessment of the selected studies

was based on the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tool for observational cohort and case-control studies.

Three independent authors conducted the searches, and any disagreements were resolved by consensus. A

meta-analysis of mortality proportions was conducted to calculate the raw, logit, and arcsine proportions for all

studies included. Heterogeneity between studies with the significance of P=.05 was assessed by calculating the

I2 value using the DerSimonian and Laird method for random effects. Odds ratios and 95% CIs for dichotomous

data, weighted mean risk differences and 95% CIs for continuous variables were calculated. Further subgroup

analyses were attempted to explore heterogeneity among over 6.7 million older adults. Leave-one-out sensitivity

analysis was conducted to assess the robustness of our results. This meta-analysis was conducted using R software

version 4.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results: A total of four studies were included in our systematic review and meta-analysis. Of the included studies,

three are retrospective cohort studies and one is an observational retrospective case-control study. As for

study group size, one cohort study was conducted on a population of less than 1000 participants, two studies

(one cohort and one case-control) involved more than 10,000 participants, and one cohort study included more

than 6 million participants. Using multiple estimators—including raw, logit, and arcsine-transformed proportions;

risk differences; and odds ratios—this study found that the mortality rate due to COVID-19 illness, and

not due to other or combined variables, among centenarian patients during the period from December 2019 to

December 2024, compared to other older adults, was not statistically significant.

Conclusion: This meta-analysis provides the first comprehensive synthesis of COVID-19 mortality in centenarians,

demonstrating that while rates are elevated, the difference from other older adults is modest and often not

statistically significant.

Keywords: Coronavirus; Pandemic; Mortality; Covid-19; Elderly; Centenarians; Systematic Review; Meta-Analysis.

Novel coronavirus cases were first detected in China in December 2019, with the virus spreading rapidly to other countries worldwide. This led WHO to declare a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on 30 January 2020 and to mark the outbreak as a pandemic on 11 March 2020 [1,2]. The aim of this study is to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies published between December 2019 and December 2024 on the rate of COVID-19 mortality in centenarians (i.e., individuals aged 100 years and older) versus older adults aged 60-99 years (hereafter referred to simply as other older adults) [3]. Since the beginning of the pandemic, more than 777 million people have contracted the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARSCoV-2) globally, and a total of over 7.1 million people have lost their lives due to COVID-19 until now [4]. Mortality of COVID-19 increases with age while children were seen less susceptible to death [5,6]. Italy was the first European country to be affected by COVID-19 [7]. The biggest cluster of cases occurred in Lombardy, the most populous Italian region, and older people were hit in the hardest way [8].

In this population, Marcon, et al. [8] questioned if the COVID-19 mortality in centenarians was lower than that in other older adults and whether sex differences exist in mortality among different age classes. Comparisons were made using total mortality (i.e., not only confirmed COVID-19 cases) at the peak of infection (March 2020) against March’s total mortality of previous years. They did not find reduced mortality in centenarians compared to non-centenarians but highlighted a difference between sexes across different age classes. While mortality in those aged 60-99 years was much higher in men than in women, the rate at which the risk increased by age was slower in men than in women, such that centenarian women had a higher mortality rate.

The authors suggested that the pro-inflammatory status of older adults, referred to as inflammageing, could explain such age-related vulnerability. Despite the observations of multiple studies measuring the mortality rate in older adults, studies concerning mortality in centenarian patients with COVID-19 remain very scarce [9,10]. Addressing this gap is essential to reinforce our understanding of the unique challenges faced by the centenarians and enable more effective health planning. This, in turn, facilitates the development of targeted treatment approaches with proper interventions tailored to the specific health needs of this demographic, particularly in situations of health crises like the COVID-19 pandemic [ 11,12,13]. In view of the foregoing, the aim of this study is to investigate the mortality rates in centenarians worldwide due to COVID-19.

The protocol for our systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted following PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [14]. Our meta-analysis study was conducted in compliance with the guidelines detailed in the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions [15].

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

PICOS (population, intervention, comparison, outcomes, and study) design for eligibility criteria [16] was adopted in this study (Figure 1). The population of interest were individuals aged 100 years and older. The intervention was testing positive for COVID-19. The comparison group were individuals aged 60-99 years. The outcome of interest was mortality rates in both populations from COVID-19. The studies included will comprise only peer-reviewed, longitudinal observational cohort and case-control studies published from December 2019 until December 2024 in English.

Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria for this meta-analysis were:

(a) Population: studies with no centenarian participants

(b) Intervention: mortality studies during COVID-19 pandemic but deaths not due to COVID-19

(c) Comparison group: individuals less than 100 years not included in the study

(d) Outcome: studies that do not present mortality rate as their effect measure

(e) Studies: those which do not fit or answer our research question.

Systematic reviews, scoping reviews, book records and research papers not available in English language will also be excluded. The restriction regarding publication time (Dec 2019–Dec 2024) is for the temporality of the COVID-19 pandemic but at the same time to widen our search window to include studies that were published after the pandemic was declared over in May 2023 [17].

Information Sources, Search Strategy, and Study Selection

PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science electronic search databases were consulted by 2 researchers on January 7, 2025, to search for studies published between December 2019 and December 2024 to identify any cohort and case-control studies that investigated the relationship between COVID-19 diagnosis and mortality in centenarians versus other older adults. The main keywords used were “centenarians” and “covid” in addition to their variations (Table 1). In the search strategy, keywords were systematically combined using the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” to refine and expand the retrieval of relevant literature. The references of the studies included in the full-text evaluation phase were reviewed independently by the 2 researchers to identify potentially relevant studies that were not considered in earlier search phases. The studies were screened against the eligibility criteria in 2 phases: title and abstract screening followed by fulltext screening. In cases of disagreement between the 2 reviewers at any stage, a consensus process was undertaken. If a resolution was not reached, a third reviewer was consulted for resolution. If data are missing or unclear, attempts will be made to contact the study authors for clarification. If contact cannot be established, the study will be excluded from our analysis, and this will be addressed in the discussion section. Science reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses found in the automated search were excluded from our study.

Data extracted from the selected studies included

1. Author and year of publication

2. Name of the journal

3. Study design

4. Country of origin of the study

5. Study objective

6. Sample size

7. Period of data collection

8. Statistical test used

9. Age of participants

10. Sociodemographic details (i.e., living alone or in a long term

care facility)

11. COVID-19 status, (i.e., positive or negative), and

12. Measured outcome.

A spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel was used to record the necessary data for running the meta-analysis. Data analyses were presented in tables and charts, and their interpretation will be discussed.

Quantitative Synthesis

To synthesize data on mortality, we calculated two effect measures: the odds ratio (OR) and the risk difference (RD) [18]. For both measures, we computed pooled estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using the raw event data extracted from the included studies. DerSimonian-Laird random effects model was used to pool risk estimates across studies. This model acknowledges that studies included in the meta-analysis may have different underlying effect sizes, rather than assuming a single true effect size across all studies, as in the fixed-effect model [19]. This means that, in addition to the within-study variability (I2), there is also between-study heterogeneity (τ²), that needs to be accounted for. Heterogeneity will be evaluated with a significance level of P=.05. Consistent with Cochrane guidelines, heterogeneity (I2) of around 25% will be considered low, around 50% moderate, and around 75% high. The arcsine transformation of proportions will be primarily considered in our meta-analyses because it stabilizes the variance of proportion data, especially when proportions are close to 0 or 1 (i.e., when studies report very low or very high proportions and variance instability is most pronounced) [20]. Arcsine transformation makes the data more suitable for standard meta-analytic analysis techniques that assume normality and homogeneity of variance. Individual study results will be visually summarized using forest plots to display both individual study estimates and the pooled estimate from the meta-analysis [15]. Meta- analyses were conducted using R software version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Subgroup Analysis and Sensitivity Test

Further subgroup analyses were conducted considering other factors such as study location, age brackets, and long-term care facility versus home dwelling to explore the heterogeneity among the 6.7 million older adults included in our study [21]. This is to help explain whether there is a variation in effect sizes across studies. Leave-oneout sensitivity analysis was conducted to illustrate how far the calculated pooled effect estimate shifts when each study is excluded, one at a time, and recalculating the pooled effect size [22]. This will help identify whether any single study disproportionately influences our overall findings and ensures that our conclusions are not unduly influenced by any single study, thereby enhancing the credibility of our synthesized evidence.

Risk of Bias and Study Quality Assessment

Funnel plots were constructed to visually assess publication bias in our meta-analysis [23]. They were structured as scatter plots, with study effect sizes on the x-axis and a measure of study precision (standard error) on the y-axis. Because visual inspection can be subjective, statistical Egger regression tests supplemented visual assessment for more robust conclusions. In addition, trim-and-fill analysis [24] were considered to assess publication bias and display the heterogeneity of the studies included in the systematic review. However, because only four quantitative studies were included in the meta-analysis, according to Cochrane guidelines, you need at least ten studies to conduct trim and fill analysis [25]. The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tool was used to evaluate the quality of observational cohort and case-control studies [26]. The quality assessment for the selected literature was evaluated independently by all authors (Tables 14 & 15)

Our preliminary search in the 3 databases resulted in a total of 101 research papers. An additional paper was found in Google scholar, totalling 102 papers. A third researcher was consulted for help with screening the 102 articles, reviewing their respective abstracts and removing duplicates. This resulted in 54 articles remaining. The 54 articles were downloaded and fully reviewed to check their eligibility for our study. A total of 19 qualitative and 4 quantitative studies were found relevant and were considered in our systematic review and meta-analysis (Figure 2). The qualitative studies were particularly valuable in guiding the methodology of our meta-analysis, informing our interpretation of the results, and shaping our conclusions. Additionally, they played a crucial role in constructing the literature review and establishing the background for our hypothesis by highlighting existing gaps in the literature. Details of the included studies are summarized in Table 2. Of the 4 included quantitative studies, 3 are retrospective cohort studies and 1 is a retrospective, case-control study. As for study group size, 1 cohort study was conducted on a population of less than 1000 participants [27], 2 studies (1 cohort [28] and 1 case-control [29]) involved more than 10,000 participants, and 1 cohort study included more than 6 million participants [30].

Quantitative Synthesis

All studies included centenarian and other older adult patients. All studies identified mortality from COVID-19 as their primary outcome. Effect estimates were calculated from the raw data retrieved from each included study. A meta-analysis was performed by pooling effect estimates from the subgroups, centenarians and other older adults, respectively. A total of 6,747,677 individuals were included for this meta-analysis, including 9,606 centenarians and 6,738,071 other older adults. Across all 4 studies, 3,519,741 mortalities were recorded, 514 of which were centenarians.

Raw, Logit and Arcsine Proportions

The raw and arcsine proportion analyses, but not logit proportion, showed that the mortality rate in centenarians diagnosed with COVID-19 is significant (Table 3).

Odds Ratio (OR)

We further analysed the data to get the combined odds ratio (OR) of all studies, to determine whether a significant relation exists. The pooled odds ratio in Table 4, suggests a possible protective effect of COVID-19 in centenarians by 19 % (OR = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.47 to 1.38, p = 0.43). However, this result is not statistically significant because the confidence interval includes 1 and the p-value is 0.43. In Figure 3, Forest Plot Depicting Pooled Odds Ratio of COVID-19 Mortality, the OR of individual studies is indicated by data markers; shaded boxes reflect the statistical weight of each study; 95% CIs are indicated by the error bars; and the overall OR with 95% CI for all studies is depicted as a diamond. An OR less than 1 suggests a protective effect (i.e., the exposure reduces the odds of the outcome). In this case, the pooled OR is 0.81, which suggests a reduction of the odds of mortality by approximately 19%. However, since the CI includes 1 and p-value is >0.05, this confirms that the association is not statistically significant.

Risk Difference (RD)

Risk difference is the probability of an outcome between two groups. It is calculated as the difference between the proportion of events in the case group and the proportion in the control group. The estimated pooled RD in Table 5. suggests 1% lower risk, or protective effect, of the outcome in the case group compared to the control group (RD = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.93 to 1.05, p = 0.69). This implies almost no difference in risk between groups. The true RD could range from 7% lower risk (0.93) to 5% higher risk (1.05); however, this effect is not statistically significant (p-value=0.69). In Figure 4, Forest Plot Depicting Pooled Risk Difference of COVID-19 Mortality, the RD of individual studies is indicated by data markers; shaded boxes reflect the statistical weight of each study; 95% CIs are indicated by the error bars; and the overall RD with 95% CI for all studies is depicted as a diamond. A RD less than 1 suggests a protective effect (i.e., the exposure reduces the risk of the outcome). In this case, the pooled RD is 0.99, which suggests a reduction of the risk of mortality by approximately 1% in the centenarian group. However, since the CI includes 1 and p-value is >0.05,, this confirms that the association is not statistically significant.

Centenarian Mortality Rate

The pooled mortality proportion in the centenarian group, according to DerSimonian-Laird random effects model, Figure 5, is 0.24, (95% CI: 0.01 to 0.62). Across all studies, an estimated 24% of centenarians diagnosed with COVID-19 experienced mortality, the true proportion falls between 1% and 62% - a wide but statistically significant range, p=0.01, Table 6. Heterogeneity Metrics: (I² = 99.80%, τ² = 0.16, p < 0.0001). I2 index measures the percentage of variability in exposure effect estimates. In other words, 99.80% of the effect estimate, mortality, is due to study differences rather than chance. τ² measures between-study variance; higher values mean more variability while Cochran’s Q test confirms significant heterogeneity P <0.05, (Figure 6).

Other Older Adults Mortality Rate

The pooled mortality proportion in the other older adults group is 0.22, (95% CI: 0 to 0.69) (Table 7). Across all studies, an estimated 22% of other older adults diagnosed with COVID-19 experienced mortality, a little less than that for centenarians (24%). Other older adults’ mortality proportion likely falls between 0% and 69% - a wide but not a statistically significant range (p>0.05). Heterogeneity Metrics: (I² = 100.00%, τ² = 0.25, p < 0.0001). The percentage of variability in exposure effect estimates is 100%. In other words, 100% of the pooled mortality estimate, is due to between study heterogeneity and not chance. τ² shows moderate variance while Cochran’s Q test confirms significant heterogeneity (p < 0.05), (Figures 7 & 8). We used arcsine proportions when running all our pooled estimate analyses because arcsine stabilises variance for extreme proportions (near 0% or 100%), handles sparse data better than raw proportions and reduces bias when event rates vary widely across studies. Contrast with OR/RD: may have been insignificant due to rare events or imbalanced group sizes, while arcsine accounts for these issues.

Leave-one-out Sensitivity Analyses

The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis plot illustrates how the pooled effect estimates from our meta-analysis shifts when each study is excluded one at a time. In Figure 9, the blue line represents the recalculated pooled estimate for each scenario, with each point corresponding to the omission of a specific study indicated on the x-axis. This visualizes the impact of each individual study on the overall meta-analytic result. The red dashed line displays the original pooled estimate, or the log odds ratio, calculated for all studies included. The x-axis lists the omitted studies, while the y-axis shows the pooled effect size, log odds ratio, for each leave-one-out analysis. The leave-one-out analysis, Figure 9, shows that although the pooled estimates (blue line) fluctuate slightly with the omission of each study, they consistently remain close to the original pooled estimate (red dashed line). Omitting any individual study does not result in a substantial change to the overall effect size, and even the largest deviations are minor. This suggests that no single study exerts a disproportionate influence on the meta-analysis results. Consequently, our findings are robust and stable, reinforcing the reliability and credibility of the overall conclusions.

Leave-One-Out Forest Plot

Figure 10 forest plot presents the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for the meta-analysis of COVID-19 mortality in centenarians. Each row shows the meta-analysis results recalculated after omitting one study. The black square represents the pooled odds ratio (OR) estimate when that study is omitted; the horizontal line is the 95% confidence interval (CI). The vertical black dashed line represents the original pooled OR with all studies included. The vertical red dotted line at OR=1 means null effect (no difference). The columns on right side show: The p-value: or the statistical significance of the pooled effect after omitting the study, tau²: Between-study variance (heterogeneity) after study omission, I²: Percentage of variability due to heterogeneity, not chance, Q: Cochran’s Q statistic for heterogeneity. Estimate [95% CI]: The pooled odds ratio and its 95% CI for each leave-one-out scenario.

Interpretation

• Robustness: The pooled OR remains close to the original estimate (red dashed line) regardless of which study is omitted. All 95% CIs overlap substantially, and none of the leave-oneout results are statistically significant (all p-values > 0.05).

• Heterogeneity: I² values remain high (>90%) in all scenarios, indicating substantial heterogeneity among studies even when any single study is omitted. Tau² and Q also remain high, reinforcing this.

• Influence: No single study, when omitted, causes a dramatic shift in the pooled effect size or its statistical significance. For example, omitting Gallert et al., 2022, increases the pooled OR to 1.08, but the CI is wide (0.60, 1.92) and still not significant. Omitting other studies yields similar patterns.

• Overall: No study unduly influences the overall meta-analytic result. Findings are robust, the pooled effect estimate, and its interpretation do not depend heavily on any single study. Heterogeneity remains high regardless of which study is omitted, suggesting variability is not driven by a single outlier. Our meta-analysis results are stable and credible; the exclusion of any one study does not significantly alter the pooled odds ratio or the overall interpretation.

Centenarian Subgroup Risk Analyses

The following subgroup analyses were conducted:

• Odds Ratio for Long Term Care Facility (LTCF)

• Risk Difference for LTCF

• Odds Ratio for Home Dwelling

• Risk Difference for Home Dwelling

• Odds Ratio in Developed Countries

• Risk Difference in Developed Countries

Odds ratio and risk difference for developing countries was not possible because we only had one study, Claudia, et al. [30], conducted in a developing country and no additional studies to compare.

Odds Ratio for LTCF

The estimated average OR suggests 14% lower odds (OR=0.86, 95% CI: 0.14 to 5.40, p=0.87) of the mortality outcome in the centenarian group compared to other older adults. The true OR ranges from 86% lower odds to more than 5-fold higher odds, however, this effect is insignificant, p>0.05, Figure 11, Table 8. Figure 12 Forest plot shows the estimated OR with 14% lower mortality odds (since OR < 1) in the LTCF centenarian group compared to the control group, however, this effect is insignificant, as the CI crosses one.

Risk Difference for LCTF

The estimated average effect suggests 4% higher risk of mortality (RD=1.04, 95% CI: 0.90 to 1.20, p=0.62) in the LTCF centenarian group compared to other older adults. The true RD could range from 10% lower risk to 20% higher risk; however, this effect is insignificant, p>0.05, Figure 13, Table 9.Figure 14 Forest plot shows the estimated average RD of 4% higher mortality risk (since RD > 1) in the LTCF centenarian group compared to the control group, however, this effect is insignificant as the CI crosses one.

Odds Ratio for Home Dwelling Centenarians

The estimated pooled OR suggests 10% lower mortality odds in home dwelling centenarians compared to other older adults (OR= 0.9, 95% CI= 0.49 to 1.66, p=0.75). The true OR could range from 51% lower odds to 66% higher odds, however, this effect is insignificant, p-value >0.05, Figure 15, Table 10. Figure 16 Forest plot shows the estimated OR suggesting 10% lower mortality odds in the home dwelling centenarian group compared to other older adults, however, this effect is insignificant, as the CI crosses one.

Mortality Risk Difference for Home Dwelling Centenarians

The estimated risk difference shows 3% lower mortality risk in home dwelling centenarians compared to other older adults (RD=0.97, 95% CI: 0.86 to 1.10, p=0.67). The true RD could range from 14% lower risk to 10% higher risk; however, this effect is insignificant, p-value >0.05, Figure 17, Table 11. Figure 18 Forest plot shows the estimated RD suggesting 3% lower mortality risk in the home dwelling centenarian group compared to other older adults, however, this effect is insignificant as the CI crosses one.

Odds Ratio for Centenarians in Developed Countries

The estimated OR suggests 6% lower mortality odds in centenarians compared to other older adults (OR=0.94, 95% CI:0.34 to 2.64, p=0.91). The true OR could range from 66% lower odds to more than 2-fold higher odds, however, this effect is insignificant, p-value >0.05, Figure 19, Table 12. Figure 20 Forest plot shows the estimated OR with 6% lower mortality odds in the centenarian group compared to other older adults, however, this effect is insignificant, as the CI crosses one.

Risk Difference for Centenarians in Developed Countries

The estimated RD suggests 2% higher mortality risk (RD= 1.02, 95% CI: 0.97 to 1.06, p=0.51) in the centenarian group compared to other older adults. The true RD could plausibly range from 3% lower risk to 6% higher risk; however, this effect is insignificant, p-value >0.05, Figure 21, Table 13.Figure 22 Forest plot shows the pooled RD suggesting 2% higher mortality risk in the centenarian group compared to other older adults, however, this effect is insignificant as the CI crosses one.

Quality assessment

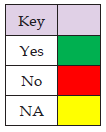

The quality of studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist (26) for case-control, and cohortstudies, respectively. Quality assessment of the studies included are displayed in Tables 14 & 15. All studies showed good quality.

Note: Q1 Were the groups comparable other than the presence of disease in cases or the absence of disease in controls?

Q2 Were cases and controls matched appropriately?

Q3 Were the same criteria used for identification of cases and controls?

Q4 Was exposure measured in a standard, valid and reliable way?

Q5 Was exposure measured in the same way for cases and controls?

Q6 Were confounding factors identified?

Q7 Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated?

Q8 Were outcomes assessed in a standard, valid and reliable way for cases and controls?

Q9 Was the exposure period of interest long enough to be meaningful?

Q10 Was appropriate statistical analysis used?

Note: Q1 Were the two groups similar and recruited from the same population?

Q2 Were the exposures measured similarly to assign people to both exposed and unexposed groups?

Q3 Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way?

Q4 Were confounding factors identified?

Q5 Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated?

Q6 Were the groups/participants free of the outcome at the start of the study?

Q7 Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way?

Q8 Was the follow up time reported and sufficient to be long enough for outcomes to occur?

Q9 Was follow up complete, if not, were the reasons to loss to follow up

described and explored?

Q10 Were strategies to address incomplete follow up utilized?

Q11 Was appropriate statistical analysis used?

We evaluated the arcsine transformed proportion of mortality in centenarians diagnosed with COVID-19 during the pandemic. Based on the results in Table 3, mortality rate within the centenarian subgroup is significant; arcsine transformed mortality proportion 0.24, CI 0.01-0.62, p-value=0.01. However, centenarian mortality OR and RD show insignificant among all participants in the study, centenarians and other older adults, OR=0.81 CI: 0.47-1.38, p-value =0.43 (Table 4), RD=0.99 CI: 0.93-1.05, p-value =0.69 (Table 5). Even after conducting several subgroup analyses, the mortality rate of centenarians appeared insignificant: Tables 8-13 and Figures 11-22, respectively. Hence the mortality rate in centenarians following diagnosis with COVID-19 could likely be due to their age-related vulnerability, immunosenescence, and/or comorbidities.

Couderc, et al. [27], found that centenarians with COVID-19 had a significantly higher mortality rate than other older adults (50% vs 21.3%, respectively), but a lower hospitalization rate, with most patients receiving supportive care in their nursing home. In the same study, centenarians also showed less symptoms, including asthenia, lower frequency fever and cough, but a higher frequency of geriatric syndromes such as delirium and falls. Also, 25% of centenarians experienced a worsening of pre-existing depression during their illness.

Gellert, et al. [28], found that centenarians had lower rates of COVID-19-relevant hospital admissions compared to younger cohorts of oldest-old residents. However, COVID-19 hospital mortality was higher in female centenarians. Notably, none of the supercentenarians (≥110 years) had a recorded hospital admission for COVID-19. The same study also indicated an elevated risk of mortality for nonagenarians (those aged 90-99) and centenarians (100+) compared to octogenarians (80-89), and for men in general. The authors suggested that lower admission rates in centenarians might reflect different treatment priorities or more stringent infection prevention measures.

Birchenall-Jinenez, et al. [30] Found that 65.47% of the affected centenarians were female, and the overall mortality rate was 37.1%, with a significantly higher rate in males, 45.24%, compared to females, 32.83%. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed greater survival in females. The average time from symptom onset to recovery was 26.56 days, while to mortality was 14.33 days. The study also revealed that centenarians were concentrated in municipalities and emphasized the increased mortality among male centenarians and the need for extended follow-up due to prolonged recovery times.

Cruces, et al. [29], found that centenarians had a higher proportion of COVID-19 cases compared to other older adults, however, centenarians appeared to exhibit extended survival after infection, with survival curves resembling those of 50-year-olds more than older age groups. In the same study, no gender differences in survival were observed among centenarians, vaccination was found to have a strong protective effect and notably, infected centenarians were not prescribed more respiratory drugs (unlike other older adults). Centenarians showed reduced use of clinical resources with fewer hospitalizations and emergency department visits, and no recorded ICU visits. The authors concluded that Basque Country centenarians showed more resistance to COVID-19 with better survival and less healthcare utilization.

Limitations

Couderc, et al. [27], The study had a limited number of centenarians (n=12), The small number of patients limited the ability to draw conclusions about the relationship between hospitalization rate and mortality rate and did not allow multivariable analysis to highlight factors influencing deaths or hospitalizations in this population. The centenarians studied were all living in nursing homes and might be more frail than home-dwelling centenarians. Moreover, The biological data was collected retrospectively from medical files, and C-reactive protein levels were missing for 26.2% of the residents, which could affect the conclusiveness of findings related to inflammation markers, overall recovery or mortality rates. Also, due to the small sample of centenarians and the lack of power of comparative analysis, few symptoms were significantly associated with age.

Gellert, et al. [28]: Although the study analyzed a large number of centenarians, mortality rates may still lack statistical power for detecting smaller effects. The study notes that the vastly lower COVID-19-related hospital admission rates in centenarians could be due to the fact that they were treated differently, with a priority for ambulant treatment or more rigorous infection prevention measures, rather than inherent resilience. This suggests a limitation in directly interpreting lower admission rates as solely indicative of better resistance. Birchenall-Jinenez, et al. [30] The absence of information on clinical comorbidities limits the ability to fully adjust for factors that might influence COVID-19-associated mortality.

The retrospective design (as in the abovementioned two studies) introduces potential biases related to the quality and accuracy of recorded data, as well as reliance on secondary records, which may affect the completeness and accuracy of the information, results and conclusions. Different categorization of municipalities and regions based on respective legislation, economic and geographical criteria may introduce variability that affects the interpretation of results at the regional level. The study notes that the age of centenarians did not appear to be a determining factor in survival but acknowledges that additional studies with larger samples are needed to confirm this finding. The study also highlights the variability in the symptom- to-recovery window, suggesting the need for close monitoring, but this variability itself could be seen as a limitation in predicting individual outcomes. The study acknowledges that while the ethnic affiliation was predominantly mestizo and white, aligning with existing evidence of the Colombian population, this might limit the generalizability of findings to other ethnic groups.

Cruces, et al. [29], The study notes that the findings regarding the response of centenarians to COVID-19 remain controversial in the broader literature, suggesting that the specific context of the Basque Country and the study’s methodology might contribute to the observed results and could be a limitation in generalizing to all centenarian populations. The study highlights that centenarians have a “younger” profile than the other older adults, implying that comparisons between these groups might be influenced by these pre-existing differences beyond just age.

In summary, common limitations across these studies include the retrospective nature of data collection, small sample sizes, potential biases in data accuracy and completeness, and challenges in generalizing findings due to specific populations and geographical contexts. The lack of detailed information on comorbidities in some studies and the potential influence of different treatment approaches further contribute to the limitations in fully understanding the impact of COVID-19 on centenarians. Confounding factors like vaccination status, COVID-19 variants/waves, and treatment measures were not highlighted nor standardized in the studies; hence several inconsistencies may arise. Further research could group patients accordingly for better representation and accountability of results. Centenarians are a rare population, small sample size provide less precise estimates, more studies are needed in this demographic to better represent their health status and needs.

Recommendations

• Future studies should aim for larger sample sizes to enable more robust statistical analyses, including multivariable analysis to identify specific factors influencing outcomes like mortality and hospitalization. As noted by Couderc, et al. [27], there small sample size limited their analysis. Expanding studies beyond single- center designs to multi-center and potentially international collaborations could facilitate the inclusion of a more diverse range of centenarians, including those in different geographical locations and living situations (nursing homes vs. home-dwelling).

• Future research could benefit from prospective and longitudinal study designs. This would allow for the standardized collection of detailed clinical, biological, and treatment data in real-time, reducing the potential for recall bias and missing information, such as detailed comorbidity data which was a limitation in the Birchenall-Jiménez, et al. [30] study.

• Future studies could delve deeper into differences within the centenarian population, such as comparing the experiences of those aged 100-105 with supercentenarians (≥110 years), as the Gellert, et al. [28], study hinted a potential difference, with no hospital admissions recorded for supercentenarians in their sample. Further investigation into gender-specific responses, as suggested by the differing mortality rates in male and female centenarians in the Birchenall-Jinenez, et al. [30] study and the higher hospital mortality in female centenarians in the Gellert, et al. [28] study, is also warranted.

• Understanding the long-term effects of COVID-19 on centenarians is crucial. Future studies should include longitudinal follow-up to assess recovery trajectories, the persistence of symptoms, and the development of any long-term sequelae in this population. The Birchenall-Jiménez, et al. [30] study highlighted the prolonged recovery time, emphasizing the need for extended follow-up.

• As mentioned by Couderc, et al. [26], future research should explore the clinical and genetic specificities of centenarians in the context of COVID-19. This could involve investigating potential mechanisms of resilience observed in some centenarian populations, such as those in the Basque Country who showed extended survival, as well as the role of the immune system and inflammaging in this aspect.

• Given the lower hospitalization rates observed in some studies and the preference for home hospitalization noted by Couderc, et al. [27], future research should evaluate the effectiveness of different treatment and care strategies specifically tailored for centenarians, considering the potential for different responses compared to other older adults.

• Finally, to facilitate comparisons across different studies and enable better meta-analyses, future research would benefit from the standardization of data collection methods and definitions for symptoms, comorbidities, treatments, and outcomes. By addressing these areas, future studies can build upon the foundational knowledge provided by the current research to offer a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on centenarians, ultimately informing better prevention and management strategies for this unique and increasingly significant demographic group.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Conceptualization: SI, WAEK-M, OMA, SC

Data curation: SI, WAEK-M, OMA

Formal analysis: SI, SC

Data investigation: SI, WAEK-M, OMA

Methodology: SI, WAEK-M, OMA, SC

Supervision: WAEK-M, SC

Writing – original draft: SI.

Writing – review & editing: SI, WAEK-M, OMA, SC

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The data supporting the findings of this study are available as Supplementary Material File.

Ethical approval is not required for this study as it is a systematic review that includes secondary data from published studies. In this study, participants are not actively recruited, and data are not collected directly from them.

PROSPERO CRD645150; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ view/CRD42025645150