Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Noriko Kurokawa1*, Katsumi Kajihara2, Miku Moriwaki4, Mutsukazu Kitano3, Ryuji Yasumatsu3

Received: December 02, 2025; Published: January 16, 2026

*Corresponding author: Noriko Kurokawa, Administration Food Science and Nutrition Major, Graduate School of Human Environmental Sciences, Mukogawa Women’s University, Nishinomiya, Japan

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2026.64.010045

Aim: We calculated the DII based on dietary and nutrient intake during the year preceding the initiation of

head and neck cancer treatment and examined the association between the DII and treatment-initiation-related

inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein [CRP]), nutrition-related indicators, and nutritional status. Furthermore,

patients were divided into two groups based on alcohol consumption and compared according to nutrition-

related indicators, nutritional status, and the DII.

Methods: We first examined the association between the DII and treatment-initiation-related inflammatory

markers (CRP), nutrition-related markers, and nutritional status. Nutrition-related indicators evaluated included

nutrient intake, hemoglobin, total leukocyte count, and serum zinc. Nutritional status was assessed using the

Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI). The DII and indicators mentioned earlier were then compared between two

groups according to alcohol consumption status.

Results: Negative correlations were observed between the DII and hemoglobin, albumin, and the PNI, whereas

no correlation was found between the DII and CRP. The non-drinking group had significantly lower energy, vitamin

B2, and vitamin B6 intake but a significantly higher DII than did the drinking groups.

Conclusion: We found no evidence suggesting that diet-induced chronic inflammation contributes to cancer

risk. Compared to the non-drinking group, the drinking group had a significantly increased DII upon treatment

initiation and a significantly decreased energy and vitamin B2 and B6 intake. This finding suggests the need for

further investigations into the DII and insufficient energy and vitamin B2 and B6 intake as factors potentially

contributing to cancer risk, other than alcohol consumption.

Keywords: Dietary Inflammatory Index; Head and Neck Cancer; FFQ; Alcohol

Abbreviations: DII: Dietary Inflammatory Index; FFQ: Food Frequency Questionnaire; PNI: Prognostic Nutritional Index; HNC: Head and Neck Cancer; CRP: C-Reactive Protein, TLC: Total Lymphocyte Count; PNI: Prognostic Nutritional Index

Head and neck cancer (HNC) is a collective term that encompasses all malignant tumors arising in various anatomical sites within the head and neck, including the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and salivary glands. Approximately 950,000 new cases of HNC are reported worldwide annually, accounting for around 5% of all cancers [1]. Although smoking and alcohol consumption have been recognized as the strongest behavioral risk factors for HNC, a significant number of non-smokers and non-drinkers still develop this type of cancer, with studies highlighting the importance of dietary exposure [2,3]. Furthermore, recent research has clarified the contribution of chronic inflammation to cancer development [4,5]. In 2014, Shivappa et al. developed the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) to quantitatively assess the impact of daily dietary habits on systemic inflammation [6]. Previous studies have reported that a high DII is associated with an increased risk of developing various cancer types [7-10]. However, only a few studies have investigated the association between HNC risk and the DII, leaving this relationship unclear. Therefore, the current study investigated the association between the DII calculated from dietary and nutrient intake data before HNC treatment initiation extracted using a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) with inflammation-related markers (C-reactive protein [CRP]), nutrition-related markers, and nutritional status at treatment initiation. Furthermore, participants were divided into two groups based on alcohol consumption and compared according to nutrient intake, nutrition-related markers, nutritional status, and DII.

From December 2023 to August 2024, patients with HNC who initiated treatment at the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Kindai University Hospital were enrolled. Among the 83 patients eligible for the NEXT FFQ, 37 satisfied the inclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria included thyroid cancer, nasopharyngeal cancer, parotid gland cancer, and failure to provide informed consent (Figure 1).

Survey Items

The survey collected data regarding patient background, which included age, gender, height (cm), weight (kg), body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2), presence of comorbidities (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, and Brinkman Index*1). Details regarding dietary and nutrient intake status were collected using a shortened version of the FFQ included in the questionnaire used in the next-generation multipurpose cohort study “JPHC-NEXT.” Nutrient intake calculations were performed using specially developed software (FFQ NEXT, Kenpaku-sha) [11]. The same interviewer surveyed the participants’ daily dietary intake starting from 1 year before treatment initiation until the start of treatment following the questionnaire format. Using these survey results, this study calculated the DII [6] score*2 by examining the intake of 26 food or nutrient parameters [12], including vitamin B12, carbohydrates, cholesterol, total fat, iron, protein, saturated fat, magnesium, zinc, vitamin A, β-carotene, vitamin D, vitamin E, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin C, monounsaturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, dietary fiber, n-3 fatty acids, n-6 fatty acids, alcohol, and onion.

• Inflammation-Related Indicators: CRP (mg/dL)

• Nutrition-Related Indicators: Hemoglobin (g/dL), total lymphocyte count (/μL), albumin (g/dL), and serum zinc (μg/dL)

• Nutritional Status: Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI)*3

1. Number of cigarettes smoked per day (cigarettes) × years smoked (years)

2. DII calculation method

• Each parameter was converted to a Z-score, which was then converted to a percentile value that was then centered by multiplying by two and subtracting by one.

• These centralized ratios were then multiplied by their respective overall food parameter-specific inflammation effect

scores to obtain the food parameter-specific DII score.

• Afterward, all food parameter-specific DII scores were combined to calculate each study participant’s overall DII score.

3. PNI: 10 × serum albumin level (g/dL) + 0.005 × peripheral blood lymphocyte count (/μL)

Method ①: For all patients, dietary and nutrient intake at the start of HNC treatment (approximately 1 year prior) was investigated, based on which the DII was calculated. The association between the DII and treatment-initiation inflammation-related indicators (CRP), nutrition-related indicators, and nutritional status was then examined.

Method ②: Patients were divided into the two groups according to alcohol consumption status, and the DII was compared with treatment initiation-related inflammatory markers (CRP), nutritional markers, and nutritional status.

Statistical Analysis

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables between the two groups. The chi-square test was performed to compare groups based on categories. Spearman’s rank correlation was used to calculate correlation coefficients. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Standard 29.0.0 statistical analysis software. A p-value of <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted after obtaining approval from the Ethics Committee of Mukogawa Women’s University (Approval No. 23- 69; October 14, 2023) and the Ethics Committee of Kinki University Hospital (Approval No. R05-140; November 15, 2023). Before participation, participants were provided an oral explanation regarding the study’s purpose, methods, safety considerations, and potential risks. The study was conducted only after obtaining informed consent.

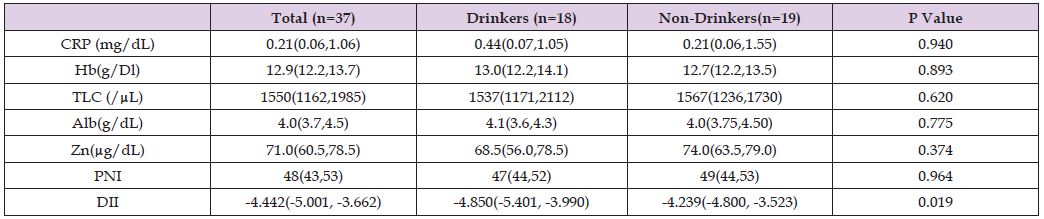

The included patients had a median age of 74 (66, 79) years and a median BMI of 19.7 (17.4, 23.5) kg/m² (Table 1). Regarding nutritional intake, the median energy intake was 23 (18, 28) kcal/kg, whereas the median protein intake was 0.76 (0.61, 0.98) g/kg (Table 2). The median DII was −4.442 (−5.001, −3.662). The median CRP level was 0.21 (0.06, 1.06) mg/dL, whereas the median serum zinc level was 71.0 (60.5, 78.5) μg/dL (Table 3). Negative correlations were observed between the DII and hemoglobin (g/dL), albumin (g/dL), and PNI (r = −0.409, −0.354, −0.439, p = 0.012, 0.032, 0.007), whereas no correlation was found between the DII and CRP (mg/dL) (Table 4). Compared to the drinking group, the non-drinking group showed significantly increased DII values (median: −4.850 vs. −4.239, p = 0.019). The non-drinking group had significantly lower energy (median: 25 vs. 19 kcal/kg, p = 0.029), vitamin B2 (median: 1.06 vs. 0.72 mg/day; p = 0.022), and vitamin B6 intake (median: 1.24 vs. 0.76 mg/day, p = 0.024) (Table 5) but a significantly higher DII (median: −4.850 vs. −4.239, p = 0.019) than did the drinking group (Tables 6 & 7).

BMI: Body Mass Index

Note: Data are expressed in medium (25 % tile, 75 % tile).

Note: Data are expressed in medium (25 % tile, 75 % tile).

CRP: C-reactive protein Hb: Hemoglobin

TLC: Total Lymphocyte Count Alb: Albumin Zn: Zinc

PNI: Prognostic Nutritional Index DII: Dietary Inflammatory Index

Note: Data are expressed in medium (25 % tile, 75 % tile).

DII: Dietary Inflammatory Index CRP: C-reactive protein Hb: Hemoglobin TLC: Total Lymphocyte Count

Alb: Albumin Zn: Zinc PNI: progonstic nutritional index

Note: Data represent Spearman rank correlation coefficients (n = 37).

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01(two-tailed test).

BMI: Body Mass Index

Note: Data are expressed in medium (25 % tile, 75 % tile).

Drinkers vs. non-Drinkers: Mann - Whitney’s U test and the chi - square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Note: Data are expressed in medium (25 % tile, 75 % tile).

Drinkers vs. non-Drinkers: Mann - Whitney’s U test.

Table 7: Inflammation-related indicators and nutrition-related indicators with Drinkers vs. non-Drinkers.

CRP: C-reactive protein Hb: Hemoglobin TLC: Total Lymphocyte Count Alb: Albumin Zn: Zinc

PNI: Prognostic Nutritional Index DII: Dietary Inflammatory Index

Note: Data are expressed in medium (25 % tile, 75 % tile).

Drinkers vs. non-Drinkers: Mann - Whitney’s U test.

DII at Treatment Initiation and Inflammation Markers (CRP)

The DII evaluates the extent to which consumed foods and nutrients promote or suppress inflammation within the body. This measure was developed based on correlations with inflammatory markers (CRP, interleukin-6 [IL-6], and tumor necrosis factor-α) [6]. Accordingly, a high DII (positive value) indicates a diet highly promotive of inflammation (e.g., saturated fats, refined carbohydrates, red meat), whereas a low DII (negative value) indicates a diet highly anti- inflammatory (e.g., vegetables, fruits, n-3 fatty acids, dietary fiber). Chronic inflammation likely facilitates processes such as accelerated protein breakdown, muscle wasting, insulin resistance, and lipid metabolism abnormalities, which promote weight loss, muscle mass loss, and decreased physical strength and increase treatment resistance and the risk of complications. Furthermore, cancer cells suppress immune responses, whereas excessive inflammatory cytokine levels may inhibit the host’s antitumor immune response against tumors, potentially increasing the risk of recurrence and metastasis. A high DII during treatment initiation reflects biological responses deeply involved in cancer progression and treatment responsiveness. Studies investigating the association between the DII and upper gastrointestinal cancers in Japan have reported a significant increase in cancer risk among groups consuming a highly inflammatory (high DII) diet (odds ratio for HNC Q4 vs. Q1 = 1.92) [8]. A study targeting a Japanese population reported a consistent positive correlation between DII scores and high-sensitivity CRP levels across nearly all age and gender subgroups, highlighting the applicability of the DII to Japanese populations [12]. Conversely, another Japanese cohort study reported that although the validity of the DII (association with inflammatory markers) was established in men, further investigation was needed in women [13]. Furthermore, a multicenter case–control study in Iran found a significant association between the DII and HNC risk [14]. Thus, the usefulness of DII as an evaluation marker at treatment initiation remains an area requiring further investigation. In the current study, the lack of a correlation between CRP levels (i.e., a marker of inflammation) at treatment initiation and the DII may be attributed to the diverse characteristics of HNC stage, treatment status, complications, and lifestyle habits (e.g., smoking, alcohol consumption). These factors could have influenced CRP levels, potentially offsetting any association with DII.

Association between the DII at Treatment Initiation and Nutritional Indicators

A high DII at treatment initiation suggests a diet with a greater potential to induce inflammation. Chronic inflammation has been thought to impact nutritional status (catabolism, muscle mass reduction, and malnutrition). Furthermore, chronic inflammation suppresses albumin synthesis in the liver, making the high DII group more likely to exhibit low albumin levels. Studies examining the relationship between the DII and oxidative stress scores have reported a correlation between higher DII levels and increased oxidative stress, which is associated with decreased serum albumin concentrations [15]. Although the median albumin level in the patients included herein was 4.0 g/dL, which was not markedly low, we found a negative correlation between albumin levels and the DII (r = −0.354, p = 0.032), supporting the findings of previous studies. Furthermore, in chronic inflammatory states, cytokines (e.g., IL-6) promote ferritin production in the liver, which impairs iron utilization and leads to functional iron deficiency. This impairment induces a state similar to iron deficiency anemia wherein decreased hemoglobin levels are observed. Therefore, elevated DII levels may potentially cause reduced hemoglobin levels. Previous studies have also identified hemoglobin as a potential negative mediator in the complex relationship between the DII and congestive heart failure/stroke, concluding that the DII, a potential factor in chronic inflammation, indirectly causes hemoglobin reduction [16]. The current study found a median hemoglobin level of 12.9 g/dL among the included patients, which was slightly low, and subsequently observed a negative correlation between the DII and hemoglobin (r = −0.409, p = 0.012). However, as mentioned earlier, we were unable to investigate the HNC stage, treatment status, complications, or lifestyle habits (e.g., smoking and drinking). Hence, further investigations are needed to determine causality.

Relationship between the DII and Nutritional Status (PNI) at Treatment Initiation

The PNI is a numerical value calculated from two blood test parameters, namely serum albumin level and peripheral blood lymphocyte count. It serves as an indicator of the balance between nutritional and immune status [17] and has been applied in evaluating various diseases (heart failure, liver disease, infections, etc.) and frailty among the elderly. The current study found a median PNI value of 48, which was mildly low. Similar to the previously mentioned nutritional indicators (i.e., albumin and hemoglobin), PNI exhibited a negative correlation with the DII. This finding indicates that patients with a high DII at treatment initiation would likely experience worsening nutritional indicators due to the effects of an inflammatory diet. Although the results obtained herein showed a negative correlation between the DII and all nutritional indicators, our sample size was limited, and background biases were not adjusted for. Nevertheless, the DII may prove to be a useful novel biomarker reflecting nutritional status in patients with HNC, provided that further studies confirm its association with nutritional indicators. Future research should track changes in the DII and nutritional indicators during treatment and validate the DII’s clinical significance through intervention studies.

Comparison Based on Alcohol Consumption Status in Patients with HNC

Smoking and alcohol consumption have been recognized as the strongest behavioral risk factors for HNC development. However, a significant number of non-smokers and non-drinkers have developed HNC, with studies underscoring the importance of dietary exposure [2]. Among the 37 patients with HNC included in this study, 19 had no history of alcohol consumption. Their lifestyle, dietary habits, and clinical characteristics may have differed from those of drinkers. In this context, we consider the DII to be a potentially useful assessment tool for examining the relationship between diet and inflammation. A previous study reported that alcohol consumption status modified the association between DII and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels” [18]. The mentioned study found that the effects of the DII differed between drinkers and non-drinkers. In particular, we found that higher DII levels correlated with higher PSA levels in non-drinkers. However, given that it did not compare the DII between drinkers and non-drinkers, further investigation is needed to confirm the results of the aforementioned study.

The current study demonstrated that non-drinkers had significantly higher DII levels than did drinkers. This result has several possible explanations. First, dietary imbalances among non-drinkers may have contributed to an elevated DII. Non-drinkers had significantly lower energy intake than drinkers, suggesting that their intake of other nutrients may have also been lower in proportion to their energy intake. In particular, vitamin B1 and B6 intake was significantly lower, whereas folate and pantothenic acid tended to be lower among non-drinkers than among drinkers, which may have indirectly contributed to increased inflammation. Second, some reports suggest that moderate alcohol consumption, especially of polyphenol-rich beverages such as red wine, may have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [19]. These effects support the hypothesis that drinkers may have relatively lower DII. As described earlier, the results of this study suggest that the development of HNC is influenced not only by alcohol consumption itself but also by the subjects’ overall lifestyle habits related to drinking and individual nutritional intake. Future studies should include a detailed analysis of the type of alcohol consumed (red wine, beer, sake, etc.), frequency, and intake volume and must adjust for confounding factors such as the age, medical history, and dietary restrictions of non-drinkers. Analyzing which foods and nutrients contribute the most to this difference in each component of the DII would also be useful.

Limitations of the Study and Future Prospects

This study was a single-center, retrospective analysis that included a small number of cases and relied on self-reported dietary intake information. Future research should include large-scale prospective studies conducted through multicenter collaboration, as well as evaluations incorporating blood inflammatory markers. Furthermore, comparative studies including patients with a history of alcohol consumption are expected to further clarify the clinical significance of the DII.

The DII at HNC treatment initiation showed a negative correlation with nutritional indicators (hemoglobin and the PNI). No significant correlation was found between the DII and inflammation-related indicators (e.g., CRP). Moreover, we found no evidence that diet-induced chronic inflammation contributes to cancer risk. Compared to the non-drinking group, the drinking group had a significantly increased DII at the start of HNC treatment. Regarding nutritional intake, energy, vitamin B2, and vitamin B6 intake were significantly lower in the drinking group than in the non-drinking group. This finding suggests the need for further investigation into the DII and insufficient energy, vitamin B2, and vitamin B6 intake as risk factors for cancer development, distinct from alcohol consumption.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.