Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Dvir Ayana1, Haitov Ben Zikri Zoya2, El Mograbi Esmael2, Bar Yehuda Sara2* and Ilgiyaev Eduard3

Received: November 17, 2025; Published: January 09, 2026

*Corresponding author: Sara Bar Yehuda, Anesthesiology Department, Shamir Medical Center, Zerifin, Israel

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2026.64.009984

Background: Patients undergoing an abdominal robotic surgery are placed in a sharp Trendelenburg position

supported by ligatures at the chest area, which could affect the respiratory pressures needed during anesthesia.

The trans-pulmonary pressure value differentiates the pressure exerted directly on the lung tissue from that

exerted on the chest wall and abdomen. Measuring the esophageal pressure is an indirect measure of the pleural

pressure and is performed using an esophageal catheter. The present study aims to evaluate the effect of the

patient’s position during abdominal robotic surgeries on the respiratory pressures.

Methods: The patients underwent a total intravenous anesthesia. Esophageal pressures and trans pulmonary

pressures were measured every 15 minutes.

Results: Data were collected from eight patients. The transition to the Trendelenburg position resulted in a

decreased respiratory volume from 535.1±63.2 ml. when connected to the ventilator, to 426.3±95.2 ml. after the

position change (P=0.005). This decrease in respiratory volumes was accompanied by a statistically significant

decrease in pulmonary compliance (P=0.02). At the same time, a statistically significant increase in esophageal

pressures was observed (Pv=0.03).

Conclusion: The data revealed that combination of a steep Trendelenburg position, chest ligation and inflation

of the abdominal cavity, as is customary in robotic surgeries, leads to a prolonged time in which the trans pulmonary

pressure is negative.

Keywords: Abdominal Robotic Surgery; Trendelenburg Position; Pulmonary Pressure; Esophageal Pressures

Abbreviations: PEEP: Positive End-Expiratory Pressure; VILI: Ventilator -Induced Lung Injury; IQRs: Interquartile Ranges; PC: Pressure Control

Abdominal surgeries performed with a robotic approach are becoming more and more common, especially in the urological and gynecological fields. Patients undergoing surgery with a robotic approach, in addition to inflating the abdominal cavity, are placed in a sharp Trendelenburg position and supported by ligatures at the chest area. All of these actions have a potential impact on chest resistance and, as a result, on the respiratory pressures needed during anesthesia and surgery [1]. Inspiratory pressures upon ventilation in a pressure- controlled ventilation or upon a volume-controlled ventilation for the same inspiratory volumes was compared during prostatectomies using a robotic ventilation. It was found that the maximum inspiratory pressures were lower in patients who were ventilated in a pressure-controlled ventilation and that the dynamic pulmonary compliance in these patients was better [2,3]. In a retrospective study that compared hysterectomies performed using a laparoscopic approach or a robotic approach, it was found that the rate of respiratory complications was higher while utilizing a robotic approach, although the average age and background morbidity in this group was also higher than among those who were operated using a laparoscopic approach [4]. On the other hand, in a review of data from colorectal surgeries conducted with a robotic approach, no increased rate of respiratory complications was found [5]. The effect of mechanical ventilation, inflation of the abdomen (pneumoperitoneum), and lying in the Trendelenburg position on the impedance (electrical resistance) of different areas of the lungs was examined.

It was found that each of these components plays a part in creating “silent spaces”, that point to areas that have been collapsed or alternatively are overdistended. The technology of measuring the pulmonary impedance cannot differentiate between the various causes of the “silent spaces”, which actually represent areas that are not properly ventilated during ventilation throughout the surgery [6]. The trans-pulmonary pressure is the difference between the pressure in the airways and the pressure in the pleural space. It actually differentiates the pressure exerted directly on the lung tissue from that exerted on the chest wall and abdomen. Measuring the intra-esophageal pressure is an indirect measure of the pleural pressure and is performed through an esophageal catheter that also contains a pressure measurement balloon. The pressure measured in the esophagus can represent the pressure at half the height between the vertebrae and the sternum. For this reason, it was recommended to adjust the positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) to values that would achieve a positive trans-pulmonary pressure [7]. In a study that examined the adjustment of PEEP in patients who underwent laparoscopic bariatric surgery, according to trans-pulmonary pressure measurements, it was found that before the abdominal inflation (in a non-robotic laparoscopic approach), the patients needed an average PEEP of 16.7 cm of water and after inflation to pressures of 23.8 cm of water on average. It should be noted that the change in the PEEP values in order to maintain a positive trans-pulmonary pressure at the end of exhalation did not result in a change in oxygenation among the patients [8].

The idea behind adjusting the ventilator according to trans-pulmonary pressures is based on the desire to prevent damage to the lung tissue as a result of over-inflation of the lung alveolus on the one hand and to prevent secondary damages to the shear forces as a result of inflation and loss of residual volume (recruitment/de-recruitment) of the lung tissue, which involve secondary pulmonary damage related to the ventilator -induced lung injury (VILI) [9]. Despite the expected implication on mechanical ventilation in patients undergoing abdominal robotic surgery, in the literature survey we conducted, we found no studies examining the changes in transpulmonary pressures, as a result of patient position and abdominal inflation, during surgery. Thus, the present study comes to evaluate the effect of the combination of a steep Trendelenburg position, chest ligation and inflation of the abdominal cavity, as is customary in surgeries with a robotic approach, on the respiratory pressures, including the trans-pulmonary pressures. The hypothesis of the study was that the combination of the position of the patient with the changes in the abdominal pressure, would increase the negative trans-pulmonary pressure and the respiratory pressures used in order to maintain adequate ventilatory status during surgery. In addition, we will examine the impact of those conditions on the state of oxygenation, ventilation and hemodynamic measures. These data can be used in the future as an infrastructure for intervention planning and changes in ventilation values in order to reduce respiratory complications in patients undergoing surgeries with a robotic approach.

Patients

Ten patients were recruited to the study during the period between 7/2019-5/2021 (the time of patient recruitment was extended, due to the COVID pandemic). The inclusion criteria were: males at the age of 18-80 years; BMI at the range of 18-35 kg/m2; ASA score of 1-2; Need for prostatectomy surgery, with a robotic approach, which requires a steep Trendelenburg position (pelvic surgeries). The exclusion criteria were: BMI lower than 18 kg/m2 or higher than 35 kg/m2.

Study Design

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (Shamir medical center, Israel), and recruited patients signed an informed consent.

Anesthesia: The patients underwent a total intravenous anesthesia, which consisted of Propofol, Remi-fentanyl and Rocuronium for muscle paralysis. The doses given were in accordance with the accepted anesthesia protocols. As is customary in anesthesia for robotic surgery, the patients had an arterial line inserted for continuous monitoring of the blood pressure and taking samples for arterial blood gas tests.

Mechanical Ventilation: The patients were ventilated with a “Hamilton” ventilator type G5 or S1. These devices are in regular use in the intensive care unit and were transferred to the operating room for the purpose of the study. The patients were ventilated with pressure- controlled ventilation - PCV, which was found to be safe and, in some studies, even more effective than the volume-controlled ventilation method, in patients undergoing surgeries with a robotic approach [3]. Inspiratory pressures were determined according to the pressure needed until a target Tidal Volume of 8-6 cc/kg predicted body weight was reached and a capnograph (carbon monitoring, exhaled oxygen report) of 35-40 mmHg was maintained. Determining the concentration of inhaled oxygen and pressures at the end of expiration (PEEP) were set according to the monitoring of oxygen saturation, at the discretion of the anesthesiologist, in the range of oxygen concentration between 30-100% and PEEP of 5-10 cm of water. Since the study was not interventional, all the adjustments in the ventilator parameters (pressure control, PEEP and oxygen percentage) were determined by the anesthesiologist in charge of the patient, within the limits described.

Insertion a Probe for Measuring Esophageal and Stomach Pressure and Drainage: After the patients were anesthetized, a Nutrient nasogastric tube was inserted, using the same technique as a normal nasogastric tube is inserted in this type of surgery (insertion from the nostril, through the esophagus to the stomach). The position of the probe was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with the help of monitoring the intra-esophageal pressure graph. A closure test was conducted to confirm the location of the measuring balloon of the catheter, in the lower third of the esophagus, at a height of between 40-55 cm. from the line of the nostril. During the end-expiratory occlusion, we gently press or squeeze the chest. The correct position is confirmed if the positive swings in esophageal and airway pressure are the same; that is, transpulmonary pressure does not change during the occlusion test. In addition to measuring pressures, the nasogastric tube was also used to drain stomach contents, as required in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgeries.

Monitored Parameters: Continuous measurements were carried out, starting from the patient’s anesthesia stage including: blood pressure, saturation, pulse, exhaled carbon dioxide, respiratory pressures monitoring (maximum inspiratory pressure, PEEP, inspiratory pressure, inspiratory oxygen concentration, as well as compliance and pulmonary resistance). Pressures recording was conducted every 15 minutes. Upon the induction of the anesthesia, placing the patient in a steep Trendelenburg position and tying the chest, inflating the abdomen, and 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes later (in cases where the operation was prolonged beyond 180 minutes even after 180 minutes), as well as at the end of the surgery (removing the instruments and emptying the abdomen of the gas) - measurements of arterial blood gases, inspiratory and expiratory esophageal pressures and trans-pulmonary pressures were taken.

Outcomes

• Primary Outcomes - the degree of change in respiratory pressures and pulmonary compliance data in patients during surgery with the robotic approach. The primary parameters the study focused on were esophageal pressures and trans pulmonary pressures. An increase of more than 20% regarding the first measurement was considered significant.

• Secondary Outcomes - the degree of change in the maximum inspiratory pressure, inspiratory pressure, pulmonary compliance and arterial Oxygen partial pressure. Here too, an increase of more than 20% regarding the baseline was considered significant.

Statistical Analysis

Data processing and statistical analyses were all performed using SPSS software, version 18.0 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL). Data with a normal distribution are represented as mean±standard deviations. Variables that did not follow a normal distribution are represented by median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) (quartiles 1-3). The two groups of continuous variables with a normal distribution were compared using a 2-sided paired t-test, while for continuous variables with a non-normal distribution, the comparison between all two groups was made using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Longitudinal data analysis was done using a mixed model. The basic models were adjusted for age and BMI. F tests were used to evaluate the significance of fixed effects, where P values of 0.05 or less were considered significant.

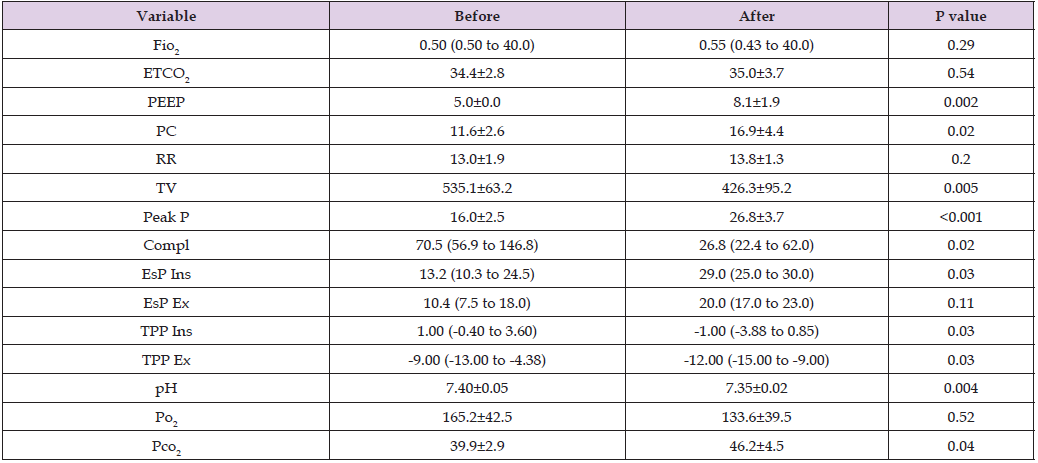

Data were collected only from 8 patients. There was a technical difficulty in inserting the dedicated probe in one of the patients. An insertion attempt was made using two sets and after the esophageal measurement balloon was torn in both during insertion, it was decided not to include the patient in the study. Another patient withdrew his consent before the induction of anesthesia. In another patient, at the final stages of the operation, before emptying the stomach from carbon dioxide, distortion was observed. The senior anesthetist in the room decided to continue the last part of the operation not solely on the basis of total intravenous anesthesia only, so gas and an anesthesia machine were also used. The mean age of the patients was 65.5±5.5 years and BMI was 26.1±3.8 kg/m2. Table 1 presents a comparison of the ventilation data and pressure measurements at three time points: before and after connecting the patients to the ventilator (in a neutral position) and after putting the patient in the Trendelenburg position, with the chest strapped. At this stage, initial changes were made to the ventilation data, allowing for the observation of the impact that lying in the described position had on the respiratory volumes, maximum pressures, pulmonary compliance as well as on the esophageal and trans-pulmonary pressures. The change in position resulted in a decrease in the respiratory volumes (tidal volume-) from 535.1±63.2 ml. when connected to the ventilator, to 426.3±95.2 ml. after the position change (P=0.005). This occurred despite the increase that was observed in the pressure control (PC) from 11.6±2.6 cm. to 16.9±4.4 cm. (Pv=0.02) and in the (PEEP) which increased from 5.0±0.0 cm. to 8.1±1.9 cm. (Pv=0.002).

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of the study participants (n=8) before and after abdominal inflation, Trendelenburg position & chest strapping.

Note: Continuous variables are expressed as means (SDs) or medians (interquartile ranges) for non–normally distributed data. A paired t-test was used to compare normally distributed variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare non-normally distributed variables. Fio2 – fraction of inspired oxygen; ETCO2 – end tidal CO2 (mmHg); PEEP-positive end expiratory pressure (cmH2O); PC- pressure control (cmH2O); RR- respiratory rate (breaths/minute). TV- tidal volume (ml); Peak P- peak inspiratory pressure (cmH2O); Compl- lung compliance (ml/cmH2O); EsP Ins- inspiratory esophageal pressure (cmH2O); EsP Ex- expiratory esophageal pressure (cmH2O); TPP Ins- inspiratory transpulmonary pressure (cmH2O); TPP Ex- expiratory transpulmonary pressure (cmH2O); PO2 – arterial oxygen partial pressure (mmHg); PCO2 – arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure (mmHg).

This decrease in respiratory volumes was accompanied by a statistically significant decrease in pulmonary compliance, from 70.5 ml/cm (range of 56.9 to 146.8 ml/cm) to 26.8 ml/cm (range of 22.4 to 62.0 ml/cm) (Pv=0.02). The measured change in the maximum pressure values (peak pressure - Peak P) was from a value of 16.0±2.5 to 26.8±3.7 cm (Pv<0.001), which was slightly higher than expected, based on the increase in PC and PEEP. At the same time, an increase in esophageal pressure was observed, where the change in inspiratory pressure was statistically significant, from 13.2 cmH2O (range of 10.3 to 24.5 cmH2O.) to 29.0 cm. (range of 25.0 to 30.0 cm.) (Pv=0.03). While there was a change in expiratory esophageal pressure, from 10.4 cm. (range of 7.5 to 18.0 cm.) to 20.0 cm. (range of 17.0 to 23.0 cm), it did not reach statistical significance (P=0.11). The PEEP measured in the ventilator demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in the imperium, from 1.00 cm. (range of -0.40 to 3.60 cm) before the Trendelenburg position to -1.00 cm. (range of -3.88 to 0.85 cm.) after lying in the position, Pv=0.03). A statistically significant decrease was also demonstrated in the emporium, from -9.00 cm. (range of -13.00 to -4.38 cm) before, compared to -12.00 cm. (range of -15.00 to -9.00 cm.) after (Pv=0.03) (Figures 1a & 1b). The monitoring of the respiratory parameters and pressures was carried out throughout the operation, once every 15 minutes. Measurements of the partial pressure of oxygen, carbon dioxide and pH were taken once every half an hour with an arterial blood gas test.

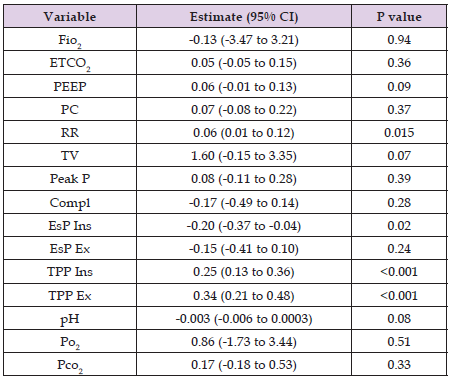

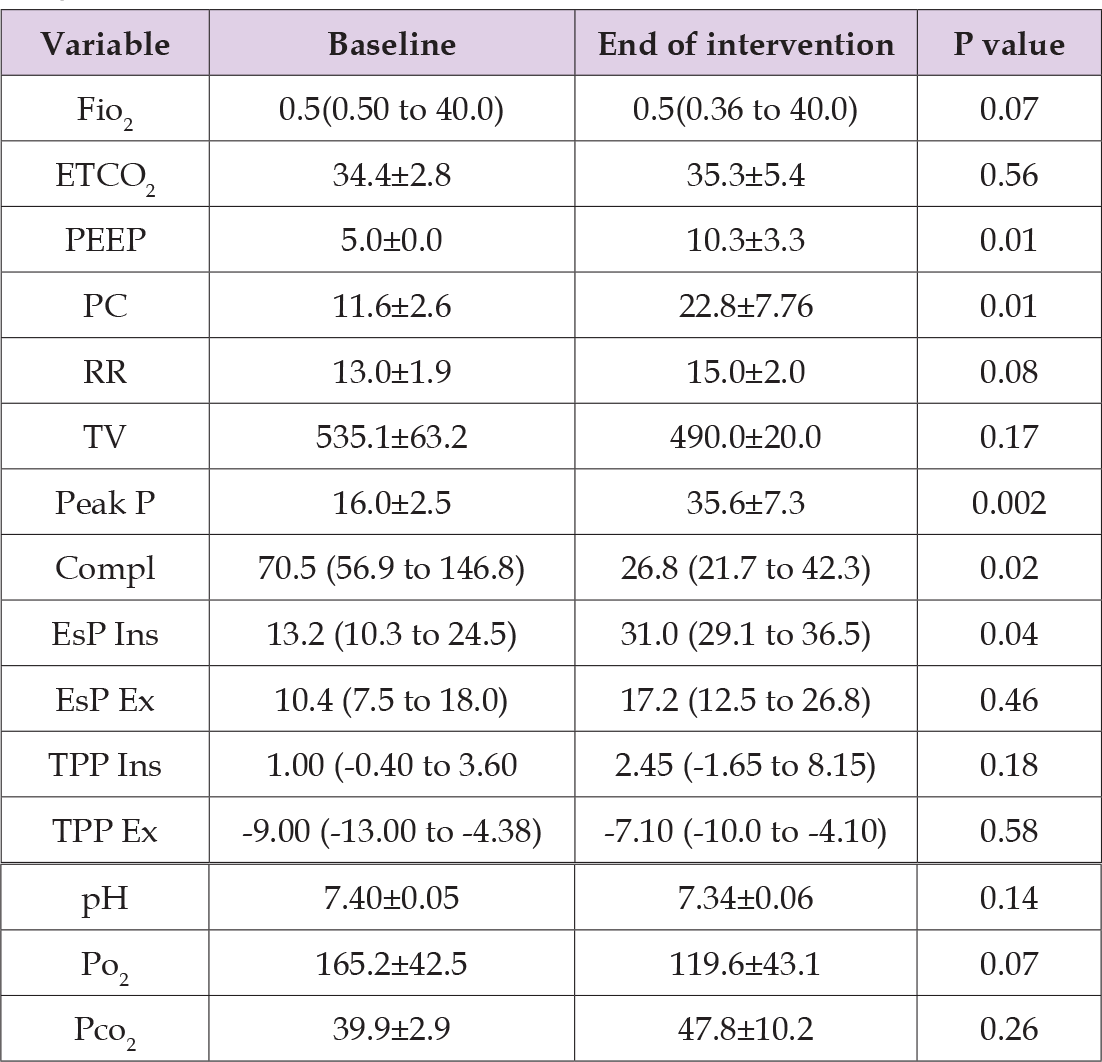

The changes of all these parameters are summarized in Table 2. After the initial adjustment which was conducted after placing the patient in the Trendelenburg position, no statistically significant changes were made in the mechanical ventilation parameters throughout the operation, except for an increase in the respiratory rate, which was significant. Pulmonary compliance also remained without significant change throughout the operation. Despite the lack of significant changes in the mechanical ventilation parameters, a statistically significant decrease in the inspiratory esophageal pressure was observed (P= 0.02) and even more pronounced, statistically significant increase in the trans-pulmonary pressures was observed throughout the operation (P< 0.001). Despite the change in these pressures, no significant change was observed in the partial oxygen pressure and carbon dioxide in the blood gases. Table 3 compares the ventilation data and the pressures measured at the beginning of the operation (before placing the patient in Trendelenburg) and at the end, after returning to a neutral position. Since almost no changes were made in the ventilation data between the last measurements during the operation and the measurement in the neutral position, it can be seen that the ventilation pressures (PEEP and PC) at the end of the operation were significantly higher compared to the beginning of the operation (PEEP of 10.3±3.3 vs. 5.0±0.0 cmH2O, P= 0.01 and PC of 22.8±7.76 vs. 11.6±2.6 cmH2O, P=0.01).

Table 2: Longitudinal changes in respiratory measurements (slopes) taken every 15 minutes after the abdominal inflation & Trendelenburg position, over 375 minutes (6.25 hours) on the basis of a mixed effects model.

Note: The table represents the mixed models with the respiratory measurements as the dependent variables. All models controlled for fixed factors, such as age and BMI.

Table 3: Comparison of respiratory and pressures characteristics of the study participants (n=8), at the beginning and at the end of the surgery (first and last measurements).

Note: Continuous variables are expressed as means (SDs) or medians (interquartile ranges) for non–normally distributed data. A paired t-test was used to compare normally distributed variables and the Wilcoxon ranksum test was used to compare non-normally distributed variables.

The other measures that were found to have statistically significant differences were the maximum inspiratory pressure (Peak P was 16.0±2.5 cmH2O at the beginning of the operation and 35.6±7.3 cm- H2O at the end, Pv=0.002) and the pulmonary compliance (70.5 ml/ cmH2O at a range of 56.9 to 146.8 ml/cmH2O at the beginning of the operation compared to 26.8 ml/cmH2O with a range of 21.7 to 42.3 ml/cm at the end). Inspiratory esophageal pressures were also significantly higher at the end of surgery. Comparing the measurements of the trans-pulmonary pressures at the beginning and at the end of the surgery, did not demonstrate any significant differences (Figures 2a & 2b).

The oncological outcomes of radical prostatectomy surgery with a robotic approach were similar to those of surgery with an open approach. However, the robotic approach was followed by a lower incidence of blood transfusions, leakage from anastomosis, surgical complications in general and significantly shorter length of hospital stay compared to the open approach [10]. At the same time, the characteristics of the surgery (steep position and chest strapping/binding, abdominal inflation and mechanical ventilation) have implications for the respiratory mechanics and the creation of collapsed areas, as well as areas of over-inflation, which affect the ventilation and oxygenation of the patient during and possibly after the operation [6]. Cammarota et al., compared the adjustment of PEEP values (airway pressure at the end of expiration) according to either oxygenation or based on esophageal pressure measurements, in patients who underwent pelvic surgeries with a robotic approach. In addition, the elastance of the respiratory system was lower in this group, compared to the oxygenation-based PEEP. The results, both the difference in oxygenation values and the elastance of the respiratory system were statistically significant [11]. Another accepted method for determining the optimal PEEP in ventilation is based on the measurement of the trans-pulmonary pressure. As mentioned, when this pressure is measured, it is common to choose PEEP at a value that will result in a positive trans-pulmonary pressure at the end of expiration, in order to reduce the risk of collapsed areas and the development of silent spaces [7].

As reported above, a laparoscopic bariatric surgery study revealed that significantly higher PEEP values were required in order to maintain a positive trans-pulmonary pressure at the end of exhalation, although this change did not result with a change in oxygenation among the patients examined [8]. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effect of the combination of a steep Trendelenburg position, chest ligation and inflation of the abdominal cavity, as is customary in surgeries with a robotic approach, on the respiratory pressures, including the trans-pulmonary pressures. Thus, monitoring and recording of respiratory pressures, esophageal pressures and trans-pulmonary pressures, while monitoring the oxygenation and ventilation parameters, was performed in 8 patients who underwent radical prostatectomy, using a robotic approach. The results of the study demonstrate that the combination of inflating the abdomen, lying in the Trendelenburg position and ligation of the thorax lead to a statistically significant increase in esophageal pressures during inspiration and a decrease to more negative values in the trans-pulmonary pressures (which were already negative in a neutral position), both in Inspirus and Emporium. At the same time, a decrease in pulmonary compliance and inspiratory volumes was measured, despite the increase in the mechanical ventilation pressures, both inspiratory and expiratory $. The decrease in pulmonary compliance remained even after returning the patient to a neutral position, as was depicted in the last measurement performed during surgery. This phenomenon may indicate a more prolonged effect of the inspiratory and expiratory phases at negative expiratory trans-pulmonary pressures over a prolonged period of time.

The research findings support the hypothesis that the combination of a steep Trendelenburg position, chest ligation and inflation of the abdominal cavity, as is customary in surgeries with a robotic approach, as well as the way the patients are ventilated during these surgeries leads to a prolonged time in which the trans pulmonary pressure is negative. Future research can try to explore whether adjusting ventilation pressures, in order to maintain a positive trans pulmonary pressure, can decrease post-surgical respiratory complications and improve ventilation and oxygenation results on blood gases.

The study was carried out in a single medical center, with a small sample size. Postoperative respiratory complications were not monitored, so it is not possible to conclude whether the significant negative changes in the trans-pulmonary pressures also had an additional clinical effect, apart from the respiratory parameters during surgery. Hence, it is suggested to investigate whether during robotic surgeries in which the Trendelenburg position, chest ligation and inflation of the abdominal cavity are involved, the ventilator should be adjusted according to the trans-pulmonary pressures, in order to maintain them in the positive desired range, which might result in a reduction in the rate of post-operative respiratory complications.