Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Vidya Shirumalla1* and Xenia Dolja-Gore2

Received: November 02, 2025; Published: November 13, 2025

*Corresponding author: Vidya Shirumalla, Staff Specialist-Pain Medicine, Central Coast Integrated Pain Service, Gosford Hospital (CCIPS), Central Coast Local Health District (CCLHD), Conjoint Lecturer, University of Newcastle, Australia

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2025.63.009956

Unfulfilled outpatient appointments despite reminders by text message and/or phone calls continue to undermine the gains established by public pain units. A study was conducted to determine if the new booking process reduces the incidence of unfulfilled appointments and associated administrative burden for patients attending individual allied health (AH) appointments in a tier 2 public pain unit, while positively impacting billable clinical activity and wait times. This new system involves pre-emptive notification of a grace period, during which the patient can ring and reschedule their missed appointment; failing to do so will result in being placed at the bottom of the list for that clinician. Vulnerable patients, however, were duly reappointed. The impact of this new booking system was primarily studied in allied health clinics where non-attendance rates were high. A statistically significant reduction in NO SHOWs from 27.12% to 11.93% (p- value 0.0041), accompanied by an increase in billable clinical time from 39.3 minutes to 52.4 minutes (p-value 0.0009), was found. The number of mean administrative contacts required to book these appointments decreased from 1.4 to 1.15 (p-value 0.009), and a trend towards a reduction in wait times was observed, with an average waiting time of 191.97 days decreasing to 152.4 days (p-value 0.087). Thus, the new booking system effectively reduces non-attendance rates for allied health appointments in a public pain unit, despite a lack of readiness to change, without disadvantaging any chronic pain patient attending this clinic.

Multidisciplinary pain clinics through the taxpayer-funded public health system [1-3] provide a vital, cost-effective, evidence-based service for patients with chronic pain [4-7]. However, unfulfilled appointments continue to undermine the gains established by these units [8]. In a review by Gurol-Urganci, et al. [9], mobile phone text message reminders were supported as a low-cost and effective intervention to increase attendance at healthcare appointments. Systematic review by Mclean, et al. titled “TURNUP” [8] found sequential intensive reminders beneficial, especially in vulnerable individuals. However, in the old booking system, despite a high administrative burden in re-booking unattended appointments and reconfirming them by phone or text message, the non-attendance rates remained high. The Behaviour Insights Team led SMS reminder system [10-12], highlighting the specific cost of a missed appointment was unlikely to incentivise the chronic pain patients who are not yet ready to change. Under these circumstances, a new approach was deemed essential.

Concomitantly, opioid reforms implemented in 2020 mandate an annual secondary review of the patient’s pain management with a second doctor if opioid treatment will exceed or has exceeded twelve months [13]. While these well-meaning opioid reforms drove up compliance with pain specialist appointments, they had no impact on patients’ readiness for change, an essential marker of patients’ compliance with multidisciplinary pain management [14-16]. Hence, the high non-attendance rates in allied health clinics continued unabated, despite reconfirming the appointments with text message reminders and/or phone calls. In this context, Painaustralia conducted a broad population-based survey to assess the impact of opioid reforms, which concluded that these reforms increased patient distress [17] and they strongly recommended improved access to multidisciplinary pain management as one of the remedial measures.

Hence, changes to the booking system were introduced to minimise these unfulfilled allied health appointments, which contribute heavily towards multidisciplinary pain management. The changes include coupling the non-attendance in the pain unit allied health clinic with a consequence. This study aimed to conduct a single-centre, controlled before-and-after study to determine whether administering a multi-faceted, new booking process reduces the incidence of unfulfilled appointments for patients attending individual allied health (AH) appointments in a public pain clinic. This study will test the hypothesis that with the implementation of the new booking system, the incidence of unfulfilled individual appointments with AH and the administrative burden of making these appointments will reduce, while having a positive impact on billable clinical activity and wait times without disadvantaging any chronic pain patient attending this clinic.

1. Study Design and Setting: This study is a prospective, observational, single-centre, controlled, before-and-after study, conducted in a tier 2 [18] public pain unit, located in a Modified Monash Model category 1 [19] region.

2. Ethics Approval: The Central Coast Local Health District Research Office approved this project (HREC Exempt Low/Negligible Risk: 0623- 066C). This is a clinician-run, unfunded study.

3. Organising for the Intervention: The principal investigator designed the new booking process. The input from the pain unit team members, primarily the administrative officer, was mainly focused on its implementation.

Intervention

The new booking process (Supplementary 1), which links non-attendance with a consequence, was developed in accordance with the then-operating NSW Outpatient Services Framework, which has since been rescinded in favour of the new Management of Outpatient (Non-Admitted) Services [20]. This new booking system allows patients one calendar month for an initial appointment and fifteen calendar days to ring and reschedule their appointment, should they fail to attend. Patients are pre-emptively informed about this consequence at the time of booking, along with appointment details, by phone, text message, letter, or email. In addition, should they fail to do so, they risk being placed at the bottom of the wait list for that individual clinician and not from the clinics of other clinicians in the pain unit. To ensure that no patient is unduly disadvantaged by this new booking system, the involved clinician reviews the notes at the time of non-attendance, looking for any obvious medical causes for non-attendance and reviewing patient’s vulnerability on account of trauma history, active mental health problems, current substance abuse issues or belonging to a disadvantaged socioeconomic demographic. These patients would receive a rescheduled appointment automatically.

Study Population

All patients attending the pain unit allied health clinic appointments during the study period.

Inclusion Criterion

The new booking system was implemented on February 6, 2023. To analyse the impact of this system, a study sample of non-attendance data was collected over a three-month period before and after the implementation. The pre-intervention group data was gathered from August 15, 2022, to November 14, 2022, while the post-intervention group data was collected from July 6, 2023, to October 5, 2023. The post-intervention group data was collected five months after the implementation because the pain clinic is typically booked at least five months in advance. Additionally, this timeframe allowed administrative staff to become accustomed to the new system and address any initial issues. Fewer unfulfilled appointments could improve patient throughput through the pain unit, reducing waiting times. A separate cohort of pre- and post-group patients was selected to study the effect on waiting time for initial clinical contact. The primary study group, which included review appointments with allied health, could not be used to study waiting times for initial clinical contact. At the time of the study, the initial clinical contact was often the initial appointment with the pain specialist. The waiting time for these initial appointments was assessed for an entire calendar month, i.e., from 15th July 2022 to 14th August 2022, which preceded the three months of the pre-intervention group. These waiting times were then compared against the waiting times for the initial appointments with a pain specialist for an entire calendar month, i.e., from 6th October 2023 to 5th November 2023, immediately after the three months of the post-intervention group. Figure 1 and Table 1 show a schematic and tabular representation of the various groups involved in this study.

Exclusion Criterion

Appointments not meeting the above criterion were excluded.

Outcomes

1. Primary Outcome

• The non-attendance rates for individual allied health appointments in the pain clinic after implementing the new booking process.

2. Secondary Outcomes

• Change in wait time after implementing the new booking process

• Clinical time spent with the patient by allied health professionals, which determines the billing generated for this appointment through the activity-based funding model.

• Administrative burden measured in terms of the total number of contacts with the patient to organise an appointment. The activity-based funding model [21] was used to measure billable clinical activity by allied health professionals, after excluding time for chart review and documentation. This is reported by allied health on service contact forms. The only billable time included in the study was the time spent with patient.

Data Sources

Data linked to the electronic medical records [22] and ePPOC questionnaires entered on epiCentre software [23,24].

Data Extraction and Management

The principal investigator collected the data and entered it into REDCap, an electronic database. All patients enrolled in the study were assigned a project identification number and de-identified before analysis. All electronic data was stored on a password-protected network and a web-based repository with limited access to authorized personnel.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical data was presented as count and percentage. The chisquare test was used to examine differences in the pre- and post-intervention groups. Categorical variables in small numbers were assessed using Fisher’s exact test. Continuous data was screened for a normal distribution and the Kruskal-Wallis test was performed for all continuous variables that did not fit into a normal distribution. All statistical analysis was performed using the SAS v9.3 software. The baseline characteristics are depicted in Table 2 and followed through in Supplementary 2. Both groups were evenly matched in age (53.7 years versus 55.7 years, p value 0.175) and sex (males 25.4% versus 34.9%, p value 0.121). However, the pre-intervention group has a higher need for assistance in at least one category (17 versus 3, p value 0.0014). Barring this, other baseline characteristics such as median number of pain sites (9 versus 10, p value 0.132) and pain psychometrics such as Brief Pain Inventory and DASS 21 were evenly distributed in every domain (Table 2). Daily morphine equivalent dose was higher in the pre-intervention group than the post-intervention group (25.19mg versus 13.18mg, respectively), but not statistically significant (p-value 0.188).

Note:

1. Fisher’s exact test has been performed

2. Kruskal-Wallis test has been performed

3. Various components of DASS 21 were missing in different patients. The total DASS 21 score could not be calculated in 12 patients in the pregroup and 6 patients in the post group.

4. Health service utilisation in the last three months from the day the referral/baseline ePPOC questionnaire was completed by the patient.

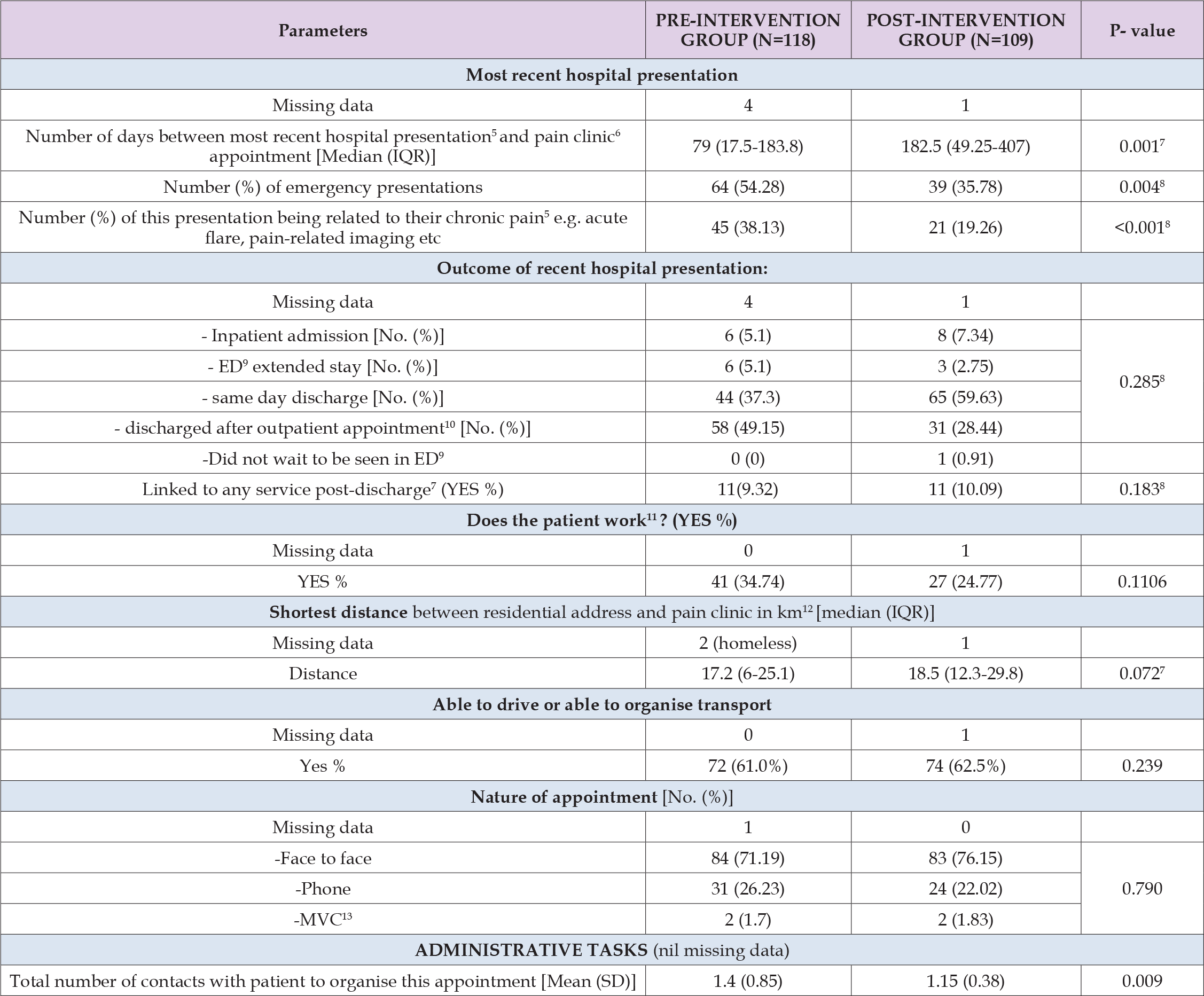

There was equal distribution of healthcare resource utilization in the last three months (Table 2) and incidence of medical conditions between both groups (Supplementary Table S1 & Supplementary 2). However, the incidence of mental health problems was higher in the pre-intervention group (Supplementary Table S1 & Supplementary 2). Likewise, the pre-intervention group had a shorter interval between most recent hospital presentation and their pain clinic appointment (mean: 79 days versus 182.5 days, p-value 0.001), had a higher percentage of emergency presentations (54.28% versus 35.78%, p-value 0.004) and were more likely to be pain-related (38.13% versus 19.26%, p-value<0.001), compared to the post-intervention group, as shown in Table 3. However, inpatient admission rates (5.1% versus 7.34%) and Emergency Department (ED) extended stay rates (5.1% versus 2.75%) were similar (Table 3). Besides, most of the patients were either discharged on the same day from outpatients (49.2% versus 28.4%) or from the ED (37.3% versus 59.6%), with linkage to additional services post-discharge not found to show any differences between groups (9.3% versus 10.1%, p-value 0.183). No significant difference was found between the pre- and post-intervention groups for work/care commitments (34.7% versus 24.8%, p-value 0.1106).

While the pre-intervention group had a slightly shorter distance between their residential address and the clinic (17.2km versus 18.5km, p-value 0.072), there was no difference in patients’ ability to get to the clinic either by themselves or with help (61.0% versus 62.5%, p-value 0.239). Face-to-face and telehealth appointments were equally distributed among both groups, with a combined p-value of 0.790 (Table 3). The administrative burden involved in booking these appointments (Table 3), measured in terms of the mean number of contacts with patients to organise the appointment, showed a statistically significant reduction from 1.4 to 1.15 contacts from preto post-intervention (p-value of 0.009). In addition to reduced administrative burden, the number of NO SHOWs (Table 4) was statistically significantly reduced from 27.12% in the pre-intervention group to 11.93% in the post-intervention group, with a p-value of 0.0041. Table 4 refers to the first allied health appointment in the study period of interest, not the patient’s initial clinical contact with the pain unit. The subsequent appointments were additional review appointments. A valid reason for non-attendance was found in 65.62% of NO SHOWs in the pre-intervention group compared to 46.2% in the post-intervention group, which is in keeping with higher rates of recent hospital presentation in the pre-intervention group. Fifteen patients in the pre-intervention group could not attend due to acute medical problems, as opposed to one in the post-intervention group.

Table 3: Factors affecting patients’ ability to attend the pain clinic appointment (Primary Sample for non-attendance rates).

Note:

5. Date of most recent hospital presentation before pain clinic AH appointment, excluding contact with pain clinic to facilitate this appointment, other

appointments with pain clinic not included in this study, or home visits by any other care provider.

6. Pain clinic appointment in the study period meeting inclusion criterion

7. Kruskal-Wallis test has been performed

8. Fisher’s Exact test has been performed

9. Emergency department

10. Includes discharge after outpatient COVID testing and COVID related phone consults

11. Including part-time, full-time, casual work or caring for family or friend

12. As per Google maps

13. My Virtual Care

Note:

14. In the study period only, and not in their overall clinical encounter with the pain clinic

15. Based on review of electronic medical records and voicemails left by patients, as well as what the clinician knew about the patient, such as upcoming

surgery or travel, etc

16. Based on activity-based funding

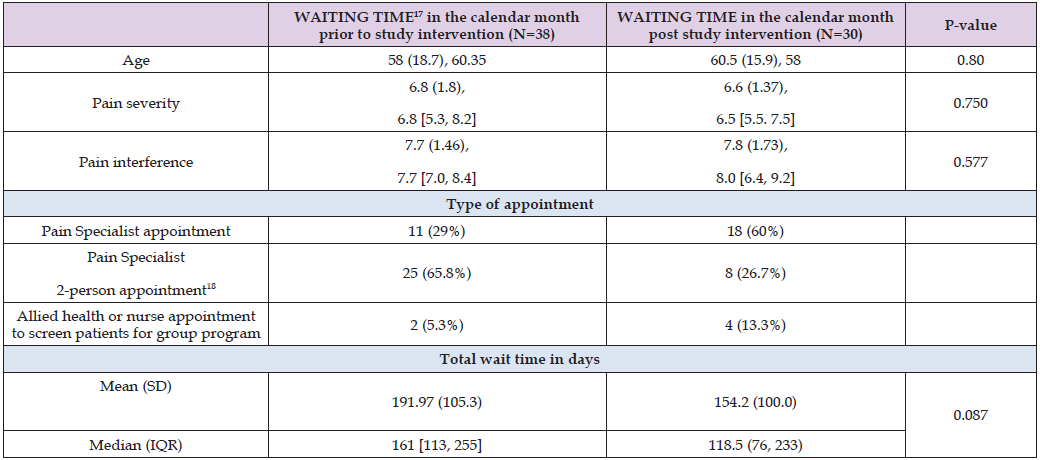

However, non-attendances ascribed to lack of motivation by the treating clinician, reduced from thirteen in the pre-intervention group to eight in the post-intervention group (Table 4). The billable clinical time spent by allied health professionals with patients, as noted in Table 4, had a statistically significant increase from a mean of 39.3 minutes to 52.4 minutes in the pre- and post-intervention group (p-value 0.0009). A reduction in unfulfilled appointments in the post-intervention group would lead to improved throughput of patients in the pain clinic. The patients who had their initial appointment in the calendar month immediately preceding the pre-intervention period waited for an average of 191.97 days compared to 154.2 days for those seen initially in the calendar month immediately following the post-intervention period. However, this trend towards reduced waiting time failed to reach statistical significance with a p-value of 0.087 (Table 5).

Table 5: Impact of “NO SHOW” reduction on waiting time from referral to initial clinical contact (secondary sample for wait times).

Note:

17. From referral to initial clinical contact

18. 2-person appointment in patients with known behavioural issues, active mental health or substance abuse problems, or known to be resistant to

change

Australians living with chronic pain are projected to increase from 3.24 million in 2018 to 5.23 million by 2050, with associated healthcare, informal care, and productivity loss-related costs expected to rise from $139.3 billion in 2018 to $215.6 billion in 2050 [4]. About 56% of these people have activities [25] concerning daily life, social roles, vocational obligations, and recreational commitments, limited by their pain [4]. An extension of best healthcare practice for these patients through multidisciplinary teams [5,6] consisting of pain specialists, psychologists or psychiatrists, physiotherapists, and other allied health professionals, who provide a combination of medical, physical, and psychological approaches, could lead to better health outcomes and substantial healthcare and productivity savings [4]. Predetermined evaluation of multidisciplinary care through public pain units by ePPOC (electronic Persistent Pain Outcomes Collaboration) consistently reports improvements in patients’ health and wellbeing outcomes [7]. Hence, despite access to multidisciplinary pain clinics in the public health system, unfulfilled appointments continue to undermine the gains established by these units [8]. Reduction of unfulfilled appointments and the associated administrative burden, accompanied by a simultaneous decrease in waiting times and an increase in billable clinical activity, has remained aspirational. This is the first study that has successfully managed to show a statistically significant reduction in pain clinic non-attendance rates, increase in billable clinical time, reduction in associated administrative burden as well as a trend towards reduction in waiting time for initial clinical contact after introduction of a new booking system where non-attendance is coupled with a consequence.

This study found a significant reduction in NO SHOWs from 27.12% to 11.93% (p-value 0.0041) between intervention groups. Concomitantly, billable clinical time spent by allied health clinicians with patients increased from 39.3 minutes to 52.4 minutes (p-value 0.0009). Additionally, the mean number of administrative contacts required to book these appointments reduced from 1.4 contacts to 1.15 (p-value 0.009) between groups. The wait times for initial clinical contact showed a trend towards a reduction from 191.97 days to 152.4 days (p-value 0.087). If a patient misses their initial appointment, they should ring and reschedule within thirty calendar days in the new booking system instead of twenty working days in the now rescinded NSW Outpatient Service Framework. Likewise, they should ring and reschedule for a missed review appointment within fifteen calendar days instead of ten working days in the latter. The new booking system liberally matched the grace period to ring and reschedule their missed appointment. Patients who fail to call during the stipulated time risk being placed at the bottom of the waitlist. When booking, the pain unit administrative officers conveyed information about the consequences of non-attendance to patients. No one was ever placed at the bottom of the wait list, as the intention was solely non-attendance deterrence without being punitive. Hence, the new booking system generated no complaints after its implementation. Additionally, rescheduled appointments were automatically offered to vulnerable patients, as this new booking system allows clinicians the discretion to do so.

Apart from complaint avoidance, this new booking system continued to cater to the needs of vulnerable individuals, as suggested in the systematic review by Mclean, et al. [8] titled “TURNUP” [8], where sequential intensive reminders were found to be beneficial, especially in vulnerable individuals. Gurol-Urganci, et al. [9] published an updated Cochrane review in 2013, in which they supported mobile phone text message reminders as a low-cost and effective intervention to increase attendance at healthcare appointments. However, in the old booking system, despite a high administrative burden in re-booking unattended appointments and reconfirming them by phone or text message, the non-attendance rates remained high. The now rescinded NSW Outpatient Services Framework [20] suggested that if a patient fails to attend two booked initial outpatient appointments or one review appointment and doesn’t respond to requests to contact outpatient clinic for a rescheduled appointment within 20 working days for an initial appointment and within 10 working days for a review appointment, they can be discharged. Additionally, in the old system if the patients were discharged on account of non-attendance, a discharge letter was sent to the referring General Practitioner who would promptly re-refer the patient, but in the absence of willingness to change the cycle of non-attendance, followed by discharge, was repeated.

As shown in Table 4, after acute medical conditions, the next highest contributor to NO SHOWs was the patient’s lack of motivation or no reason. It is well known that patients who are not ready for change don’t comply with multidisciplinary care [14-16]. A Behaviour Insights Team-led SMS reminder system [10-12], highlighting the specific cost of a missed appointment, was unlikely to incentivise chronic pain patients who are not yet ready to change. Consequently, there was a compelling need for a different approach. The 75th percentile for waiting times for initial clinical contact was 255 days versus 233 days in the two groups being compared (Table 5). Hence, the suggestion of being at the bottom of a wait list, should they not ring and reschedule within the stipulated time, appeared to be an effective deterrent for non-attendance. The new booking process was effective in reducing non-attendance rates in these complex patients, with extremely severe baseline mean DASS 21 scores of 56.41 in the pre-intervention group and 43.36 in the post-intervention group, a high incidence of mental health conditions (Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary S2), and clinically significant catastrophisation as evidenced by mean baseline Pain Catastrophising Scale of 30.25 in the pre-intervention group and 21.73 in the post-intervention group (Supplementary Tables S1-S3).

Note: aMore than one condition in a patient.

Note: bTotal PCS missing data represents patients who did not enter any data in any of the 3 domains of PCS in their baseline ePPOC questionnaire. Those with some parts missing but still meeting ePPOC threshold for calculation, were incorporated in mean (SD) Calculations. ePPOC threshold for calculating a valid PCS score: At least 12 of the 13 items must be completed by the patient to calculate a valid total PCS score. If more than one number has been circled for a question, use the highest score.

Note: cGroups of medications include opioids, paracetamol, NSAIDS, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines and medicinal cannabinoids.

Studies conducted by Giummarra, et al. [26] and Odonkor, et al. [27] examined factors affecting patients’ ability to attend clinic appointments, such as recent illness, distance from the pain clinic, work/ care commitments, and ability to get to the appointment, and suggested incorporating the same while planning patient flow through the pain unit. In our study, the most recent hospital presentation was observed in the lead-up to the pain clinic appointment during the study period. While the pre-intervention group had more pain-related ED presentations closer to their pain clinic appointment than the post-intervention group, there was no difference in rates of their inpatient admission, ED extended stay, discharge on the same day from ED or outpatients, and linkage to additional services post-discharge (Table 3). Both groups were also comparable regarding work/care commitments (34.7% versus 24.8%, p-value 0.1106). Of the two groups, the pre-intervention group lived closer to the pain clinic (17.2km versus 18.5km, p-value 0.072), but this didn’t seem to affect the ability of patients in the post-intervention group to get to the appointment either by themselves or with some help (61.0% versus 62.5%, p-value 0.239). The pre-intervention period was in late Australian spring and early summer, while the post-intervention period was in late Australian winter and early spring; thus, neither study period included peak winters or summers [28]. Additionally, face-to-face and telehealth appointments (Table 3) were equally distributed in both groups (combined p-value 0.790).

There was an equal distribution of factors that affected pain clinic non-attendance in both groups. Yet, there was a statistically significant reduction in non-attendance rates in the intervention group, which also had a reduced administrative burden. Time limits around pre-emptive cancelling of booked appointments were not placed, as imposing anything more stringent than what is already laid out in the new booking system might be perceived as punitive. This led to last-minute cancellations, which could not be re-booked. Hence, the gains from the reduction in non-attendance and administrative burden were only partially realised. Additionally, due to unexpected resignations and unplanned leave, the pain unit remained identically short-staffed during pre- and post-intervention study periods. This stymied the throughput by limiting the maximum number of consultations possible. Hence, the trend towards reduced waiting time didn’t assume statistical significance. Chronic pain patients who are not ready to change often refuse to engage with health care [14]. The intricate problem of facilitating healthcare engagement by this disenchanted group has been acknowledged time and again [16]. However, solutions often revolved around sending more frequent reminders and introducing the positive or negative financial implications of their attendance or its lack thereof in these text message reminders [8-12]. Before the study, non-attendance at allied health clinics remained challenging despite repetitive reminders and a high administrative burden.

The study intervention, linking a consequence to non-attendance, helped set the much-needed behavioural boundaries in a taxpayer- funded free universal healthcare system [1-3]. Additionally, the study intervention maintained a delicate balance between deterrent and overly punitive action. The intervention is still in use in the author’s pain unit, and the new booking system also includes appointments with pain specialists. Since the introduction of opioid reforms in 2020 [13], mandatory support for opioids by pain specialists has promoted compliance with pain specialist appointments. However, with the reduction in the use of opioids in Australia [29] and the concomitant unregulated escalation in use of erratic doses of medicinal marijuana [30-32], relevance of a non-attendance deterrent policy in a taxpayer-funded universal healthcare system is now more evident than ever.

The new booking system was smoothly implemented without generating a single complaint. Highly vulnerable individuals were duly re-appointed without any penalty.

As the patients often cancelled remarkably close to the time of the booked appointments, they could not be re-booked. Hence, despite an effective non-attendance deterring policy, re-booking of unfulfilled appointments remained sub-optimal. Only a small fraction of patients in both pre- and post-intervention groups had repeat appointments during the three-month study period, so it was underpowered to detect non-attendance rates in repeat appointments.

The new booking system effectively reduces non-attendance rates in chronic pain patients, with a concomitant reduction in administrative burden and improved billings from allied health clinics due to increased activity

Further research should be directed at strategies that facilitate the timely re-booking of last-minute cancellations.

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors thank Mrs Angela Lunney, the pain unit administrative officer, for her help in implementing the new booking process.