Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Thomas Andrea Nkhonjera1*, Lydia Kishindo Mafuta2, Victor Kasulo3, Hope Msolola4 David John Musendo5 and Chrispin Botha6

Received: May 17, 2025; Published: May 26, 2025

*Corresponding author: Thomas Andrea Nkhonjera, Department of Agri-Sciences, Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Mzuzu University, P/Bag, 201, Mzuzu, Malawi

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2025.62.009691

Global and national policy frameworks of early childhood development emphasise the importance role of family involvement in early childhood education. Nonetheless, there remains limited determining factors of parents and other family members on children’s transition from Community-Based Childcare Centres (CBCCs) to mainstream primary education within the Malawian context. This study sought to examine the familial determinants that influence the transition process of children from CBCCs to public primary schools, focusing on an urban setting in Mzuzu City. Using a quantitative research design, the study collected data from a representative sample of 408 households, selected through purposive sampling techniques. Data were collected using a structured household questionnaire and analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 29. Descriptive statistics and binary logistic regression models were employed to determine the strength and significance of associations. Findings indicate that 85% of caregivers perceived their children’s transition to primary education as successful, despite notable challenges related to social adaptation and academic adjustment. Parental involvement was found to be a significant factor of successful transition outcomes (odds ratio = 3.45, p < 0.01), whereas difficulties associated with adapting to new school environments were negatively correlated with successful transitions (odds ratio = 0.67, p < 0.05). These results underscore the critical role of active family engagement in facilitating children’s transition from CBCCs to primary education. The study recommends community outreach and parental guideline frameworks to raise awareness on timely school enrolment, alongside economic empowerment for low-income families. It urges primary schools to enhance parental involvement through workshops and communication. At the policy level, inclusive education frameworks and stronger school-community partnerships are needed to support smoother, equitable transitions for all children.

Keywords: Parent; Family; Caregiver Engagement; Child Transition; Early Childhood Development; Community Based Childcare Centres

Early childhood development (ECD) has gained global recognition for its foundational role in lifelong learning and well-being of every child. In Malawi, Community-Based Childcare Centres (CBCCs) provide essential preschool education, yet the transition from these centres to formal primary education remains a critical and often under- supported phase (Munthali, et al. [1]). This study examined parents and families’ experiences, challenges, and strategies surrounding children’s transition, with a particular focus on enhancing preparedness through effective parental family involvement. For the purposes of this study, the term ‘parent or family’ is defined as any primary caregiver or legal guardian who holds custodial responsibility for a child aged between 3 and 5 years, both within the household setting and at the CBCC level. Global literature affirms that parental engagement in early learning significantly improves school preparedness, academic performance, and retention (Lim, et al. [2]).

However, in low-resource contexts such as Malawi, this involvement is often constrained by socioeconomic challenges, competing responsibilities, and limited access to information (Bwezani, et al. [3]). It is also argued that systemic barriers, including inadequate infrastructure and weak communication with educators, further hinder meaningful parental participation (Munthali, et al. [1]). This study explored how family structures, and information asymmetries influence parental involvement, drawing on evidence that traditional parent- teacher hierarchies often limit collaborative partnerships (Clarke, et al. [4]). Therefore, by integrating global and local perspectives, this research contributes to the discourse on inclusive and sustainable parental involvement in early childhood development and education. It calls for contextually relevant strategies that can enhance communication between the family and school, build trust among caregivers, parents and teachers, and align with the cultural and socioeconomic realities of families in Malawi.

Background

Globally, different scholars argue that the transition from early childhood education to formal primary schooling is a critical phase in a child’s development, influencing future academic and social outcomes (Lim, et al. [2]). (Table 1) The Sustainable Development Goal 4.2 and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (Article 28) emphasise universal access to quality early learning and the role of families in supporting this transition (UNESCO (2015)). In agreement, studies show that children’s smooth transitions lead to improved academic, emotional, and social performance (Besi [5]). Among others, studies argues that key enablers of smooth children’s transition to primary school include parental participation, socioeconomic status, and access to learning materials (Lim, et al. [2]).

Scholars like Soni, et al. (2022) argue that in Sub-Saharan Africa, challenges of children’s smooth transitions are magnified by poverty, parental illiteracy, and disparities in educational quality. Similarly, research in Kenya, Uganda, and Ghana highlights the need for continuity between early childhood education and primary school, with family involvement and financial stability playing crucial roles (Akwara, et al. [6]). Consistent with this perspective, the 2024 UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report emphasizes the critical need to establish coherent linkages between community-based early childhood education programmes and formal education systems as a prerequisite for achieving equitable and positive educational outcomes for all children.In Malawi, Community-Based Childcare Centres (CBCCs) are essential for early education in low-income areas. Policies such as Malawi Vision 2063, National Education Sector Investment Plan (2020–2030), and the Early Childhood Development Policy (2017) emphasise integrated approaches and parental engagement in the education of children (Government of Malawi, 2017; Ministry of Education, 2020). However, research has focused more on infrastructure and resources than on family dynamics (Rouse, et al. [7]). This study addressed the gap by exploring how parental and family factors affect children’s transition from CBCCs to public primary schools in Mzuzu City.

Problem Statement

Despite increasing global recognition of the significance of early childhood education and international commitments to facilitate smooth children’s transition from early learning environments to formal schooling, limited scholarly attention has been directed toward understanding the determinants of parents and families in supporting this critical transition process. This gap presents a pressing challenge, particularly in low-resource contexts, particularly, Malawi where familial engagement is essential yet often overlooked in policy and practice frameworks. In Malawi, Community-Based Childcare Centres serve as foundational institutions for preschool learning, particularly in low-income urban and rural settings. However, Munthali, et al. [1] argue that the transition of children from CBCCs to formal primary education is often hindered by a lack of family preparedness, limited institutional support, and inadequate parental engagement. Although existing studies on early childhood education in Malawi have largely concentrated on infrastructural and resource availability, there is a notable limited of empirical research examining the role of parental and familial dynamics in shaping children’s transition outcomes from community-based childcare centres to formal primary education. This gap is particularly pronounced in urban settings such as Mzuzu City, where evolving social structures and economic pressures may uniquely influence the nature and effectiveness of family engagement during this critical educational phase. At the same time, this gap in research limits the ability of policymakers and educators to develop targeted interventions that facilitate equitable and effective transitions. Understanding the familial determinants of transition success is thus critical for informing inclusive education strategies, community engagement frameworks, and child-centered policy reforms.

Research Objectives

1. To explore the challenges faced by families in facilitating

their children’s transition from Community-Based Childcare Centres

(CBCCs) to formal primary education in Mzuzu City.

2. To analyse parental and familial factors that contribute to

successful transitions from CBCCs to primary schools.

3. To examine the relationship between parental involvement

and children’s readiness for formal schooling.

Research Questions

1. What challenges do families in Mzuzu City encounter in supporting their children’s transition from Community-Based Childcare Centres (CBCCs) to formal primary education?

2. What parental and familial factors contribute to the successful transition of children from CBCCs to primary schools? 3. In what ways does the level of parental involvement influence children’s academic and social readiness for formal schooling?

Significance of the Study

Transition from early childhood education to primary school is globally recognised as important to a child’s future academic journey, yet this period remains poorly supported in many low-resource contexts. In Malawi, Community-Based Childcare Centres play a central role in early learning, but structural and systemic weaknesses often prevent children from making smooth transitions to formal schooling. While national policies such as Malawi Vision 2063 and National Education Sector Investment Plan (2020 –2030) underscore the importance of integrated early education and family engagement, there is a research gap regarding the lived realities of parents and families during this transitional phase. Therefore, this study is justified by its potential to fill this empirical gap, offering an understanding of how familial determinants such as parental attitudes, socioeconomic status, and household dynamics affect children’s transition in urban settings like Mzuzu City. It also aligns with international commitments such as Sustainable Development Goal 4.2 and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which call for early educational access and family-centered development strategies. The findings inform educators, policymakers, and child welfare stakeholders on how best to strengthen family-school linkages and ensure equitable early learning transitions for all children in Malawi.

Theoretical Framework: Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1979) suggests that child development is shaped by a dynamic interplay of environmental systems that are nested within each other. These systems extend from immediate settings with direct interactions to broader societal and cultural contexts, each contributing to a child’s developmental path in interconnected ways. The theory outlines five interrelated systems that collectively influence the child’s growth and learning experiences. At the most immediate level, the microsystem refers to environments where the child directly interacts with people and institutions, such as the family, Community-Based Childcare Centres (CBCCs), and schools. The mesosystem captures the interconnections among these microsystems, such as the quality of collaboration and communication between families and childcare providers.

The exosystem includes broader social structures that do not directly involve the child but still apply an indirect influence, such as parental workplace policies and local governance structures. The macrosystem encompasses the overarching cultural, economic, and policy environments that shape societal values and expectations regarding child-rearing and education. Lastly, the chronosystem introduces the dimension of time, considering life transitions and historical or socio-political events that influence development across different stages of life. In the context of the study on parental and familial determinants of successful transition from Community-Based Childcare to primary education in Malawi, Bronfenbrenner’s theory offered a comprehensive framework for analysing how various layers of environmental influence affect a child’s readiness and adaptation to formal schooling. The microsystem played a central role in evaluating how parental involvement, family practices, and the quality of CBCCs directly shaped children’s transition outcomes. Through the mesosystem, the study examined the strength of relationships between parents and CBCC caregivers, focusing on how such interactions facilitated or hindered the transition process.

The ecosystem provided insight into the indirect effects of external socio-economic factors, such as employment patterns of parents and the availability of community resources, which impacted children’s preparedness for school. At the macrosystem level, the study reflected on how national education policies, prevailing cultural beliefs about early childhood development, and structural poverty influenced parental expectations and the general approach to school transition. The chronosystem enabled the researcher to account for the influence of long-term societal changes and events, such as educational policy shifts or the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, on children’s transition experiences over time. By applying Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, the study was able to systematically investigate the complex and interdependent nature of parental and family influences on children’s transition from CBCCs to public primary schools in Mzuzu City, Malawi. This theoretical framework enhanced the analysis by placing individual family behaviors within their broader contextual environments, thus providing a holistic understanding of transition dynamics in a low-resource urban setting.

Parental involvement is recognised as a critical aspect of effective Community-Based Childcare Centre (CBCC) and school governance. Its significance stems from evidence suggesting that the approaches and policies adopted by CBCC and school leadership to engage parents play a more decisive role in shaping parental participation in education than do familial background factors such as socioeconomic status, ethnicity, race, or marital condition (Epstein [8]). However, it is hypothesized that the progression of children from CBCC to formal primary education in Malawi is profoundly influenced by parental and household-level determinants, particularly socioeconomic status, ethnicity, religious affiliation, and marital status. In agreement to the hypothesis, Munthali, et al. [1] argue that CBCCs play an important role in the early childhood development framework by providing foundational learning, psychosocial support, and nutrition to children aged 3 to 5. Similarly, Jolley, et al. [9] emphasises that the success of this transition relies not only on institutional efforts but also on supportive home environments.

Parental Participation in Education of their Children

In the early 19th century, education in many parts of the world including Africa was predominantly a domestic responsibility, with parents serving as the primary educators of their children (Garcia, et al. [10]). In the United States, for example, white families generally provided home-based instruction unless they were affluent enough to afford private schooling. During this period, the establishment of public schools marked the beginning of formalized, state-supported education across all grade levels. Community involvement was integral, as parents actively contributed to the construction of one-room schoolhouses and participated in selecting teachers through public voting mechanisms. These early school settings were resource-constrained, prompting a continued reliance on home instruction and parental support. Parents routinely assisted with learning at home, which not only supplemented school instruction but also alleviated financial burdens on local authorities.

The educational histories of many African countries, including Malawi, trace similar trajectories. The formalization of parental engagement in education gained prominence in the latter half of the 19th century (Munthali, et al. [1]). This shift reflected a transition from an instructional model where parents contributed directly to learning at home, to one in which professional teachers assumed central responsibility for curriculum delivery (Anfara [11]). As the teaching profession became more institutionalized, parental involvement gradually became more confined to structured school activities. Consequently, parental voices were increasingly marginalized, particularly during the 20th century, as involvement became bureaucratically regulated. The emergence of childcare facilities, especially to accommodate working and college-going mothers redefined the parental role in education. Parents who had previously stayed at home were now enlisted to support teachers in these early childcare settings (Tekin [12]). Throughout this era, socioeconomic stratification began to shape patterns of parental participation, with involvement often reflecting class distinctions (Tekin [12]).

A growing divide between home and school placed increasing control over parental involvement in the hands of teachers. According to (Anfara [11]), this shift positioned educators as the primary authorities on children’s education, limiting parents to peripheral roles, often restricted to supporting extracurricular activities under teacher supervision. The motivation for meaningful parental engagement began to diminish as professional educators defined classroom priorities and educational standards. Jolley, et al. [9] argue that toward the end of the 19th century, schools increasingly distanced themselves from families, reinforcing the perception of teachers as exclusive custodians of educational expertise.In Malawi, the Education Act of 2013 introduced a modern framework that formally acknowledged parental involvement as essential to student achievement in the 20th century (Munthali, et al. [1]). The Education for All (2004) initiative was the first major policy in Malawi to explicitly promote parental engagement in the schooling process (Anfara [11]). This initiative emphasized inclusivity by urging schools to connect with parents across diverse cultural, linguistic, and national backgrounds. In response, schools began to diversify their staff and develop multilingual communication materials to facilitate broader parental participation. Subsequently, the Education for All framework evolved into additional policies and strategic actions aimed at institutionalizing parental involvement within the Malawian education system (Greenwood, et al. [13]). On the global stage, parental engagement has received increasing emphasis in both international and domestic education policies (Gladstone, et al. [14]). While often regarded as an end, many parents view their involvement in school governance primarily to improve their children’s academic outcomes (EFA, 2008). However, the assumption that devolving decision-making power to parents, schools, and communities automatically results in pro-poor benefits remains insufficiently substantiated. Pryor [15], in a study on parental and community involvement in rural education improvement in Ghana, argued that while community participation is a valuable objective, its true significance lies in enhancing school development, which in turn fosters a sense of communal ownership around educational institutions (Figure 4).

Dynamics of Parental Involvement in Education of Children

Epstein [8] conceptualizes parental involvement as comprising two primary dimensions including school-based and home-based engagement. School-based involvement encompasses activities such as participation in parent-teacher meetings, decision-making forums like Parent-Teacher Associations (PTAs), volunteering within the school environment, and occasionally undertaking delegated responsibilities, including infrastructure support. Similarly, Clarke, et al. [4] describes parental engagement in education as a multidimensional and collective process. For instance, in the Malawian context, CBCC or school construction is frequently undertaken as a collective community initiative, wherein families under the leadership of traditional authorities contribute resources such as housing for teachers or classroom blocks (Lynch, et al. [16]).

Additionally, parental involvement has been defined as a set of interactions between parents and their children, and between parents and school personnel, that contribute to children’s academic development and learning outcomes (Abdullah, et al. [17]). In agreement, Sunny, et al. [18] conceptualize parental engagement in education through three interrelated domains including home-based involvement, such as parenting practices, educational support at home, and supervision of schoolwork; episodic school involvement, such as participation in school meetings and specific events; as well as sustained school engagement, involving volunteering, regular collaboration with educators, and consistent school-family communication.

Musendo, et al. [19] characterizes parental involvement as a process through which parents actively participate in a variety of educational engagements that support their children’s learning. Likewise, Nye, et al. [20] describe it as deliberate interaction between parents and their children beyond school hours, aimed at enhancing academic achievement. Similarly, Walker, et al. [21] focus on the cognitive and psychological dimensions of parental participation while Sunny, et al. [18] expand this view by suggesting that parental involvement is shaped by internal beliefs, values, and perceptions about education of their children. Furthermore, literature argue that a positive school climate and welcoming school staff are crucial for fostering parental motivation to participate. According to Rouse, et al. [7], parental involvement may also manifest through support with homework and monitoring academic progress. As such, it can be concluded that for learners to fully benefit from both CBCC and formal education, the engagement and support of parents are essential. Therefore, efforts to improve parental participation in education must be central to the agendas of policymakers, school administrators, educators, and parent organizations. This is backed up by Kraft [22] who identify three key elements that promote parental engagement including strong teacher-student relationships, expanded parental involvement, and enhanced student motivation. Therefore, effective parental participation can be considered equally vital as teacher instruction in promoting student success because literature argues that children with more involved parents tend to perform better academically (Machen [23]).

The Benefits and Challenges Associated with Parental Involvement in Education

Literature indicates that fostering strong communication and collaboration between schools and families benefits not only students but also parents and educators (Loudová, Havigerová & Haviger, 2015). According to (Ng, et al. [24]), when parents are engaged with teachers, children’s self-esteem and self-concept are more likely to improve. To support and institutionalize effective parental involvement, Okeke [25] proposes eight strategic interventions: enacting a national parental involvement policy; integrating parents in curriculum discussions; organizing parents’ evenings; conducting home visits; establishing childcare policies within schools; arranging parent- teacher social activities; hosting school debates and speech days; and strengthening parent-teacher associations (PTAs). However, challenges remain. Bwezani, et al. [3] findings indicate that many parents are unclear about their roles in educational settings. Similarly, Clarke, et al. [4] observed that some parents feel inadequately prepared to engage due to their limited educational backgrounds. Furthermore in most developing country like Malawi contexts, the learning environment within CBCC and schools have been shown to have a more pronounced impact on student outcomes than parental involvement primarily due to widespread parental illiteracy or low educational attainment, cultural and socioeconomic contexts, financial burdens to secure their children’s education, driven by aspirations that their children surpass their own educational accomplishments (Murphy, et al. [26]).

Additionally, despite the acknowledged importance of early childhood development in national policy, the quality of CBCCs in Malawi remains low. Kholowa [27] attribute this to the prevalence of untrained caregivers, minimal parental participation, and the absence of structured transition pathways. Neuman, et al. [28] highlighted similar limitations, noting inadequate learning resources, reliance on volunteer staff, food insecurity, and weak family engagement. While caregiver training can improve professional practices, Jolley, et al. [9] found such improvements did not yield statistically significant outcomes unless coupled with community and parental engagement.

Broader socioeconomic conditions further influence child development as Greenwood, et al. [13] revealed that poverty and nutrition deficits hinder caregivers’ capacity to support early learning at home. Additionally, Dizon-Ross (2016) found that many Malawian parents misjudge their children’s academic ability, particularly in low-literacy households, affecting educational investment.

Furthermore, parental engagement is believed to be influenced by socioeconomic status, time constraints, and cultural norms. Sapungan [29] identify poor communication, low literacy, and negative parental attitudes as barriers, a view echoed by David, et al (2024) in the Malawian context. According to McLinden, et al. [30], cultural expectations, such as children’s domestic participation, may conflict with formal education routines complicating transitions. Additionally, family structure matters as Banda, et al. [31] report that children with active parental not extended family engagement showed better motivation and confidence. These findings emphases the need for integrated support systems linking livelihoods and early education to the participation of parents. In connection, legal frameworks also shape parental roles as Mkandawire, et al. [32] critiques Malawi’s Child Care, Protection and Justice Act for prioritizing parental control over child agency.

In conclusion, parental involvement in school management across several African countries faces numerous challenges rooted in socioeconomic, institutional, and cultural factors. Majamanda, et al. [33] highlighted that parents with limited education often withdraw from school activities due to feelings of inadequacy, illiteracy, and a lack of confidence in their capacity to contribute. These barriers are compounded by an unwelcoming institutional environment, limited awareness of parental rights, and insufficient communication between schools and families. In Malawi, parental contributions have historically focused on construction and fundraising rather than active participation in school governance (Chilemba [34]). Munthali, et al. (2008) argues that the implementation of Universal Primary Education created confusion about community roles, weakening parental engagement. Similarly, scholars like Itimu [35] observed that although parent-teacher associations and school committees are mandated take participate in the education of all children, many remain inactive, and efforts to promote parental involvement remain fragmented and poorly coordinated.

Description of the Study area

This study was conducted in Mzuzu City, situated in northern part of Malawi, at roughly 11.47° S latitude and 34.02° E longitude. Mzuzu has a robust educational infrastructure, which includes 107 community- based daycare centers staffed by more than 3,000 caregivers and servicing 15,232 children (NSO [36]). This shows the city’s considerable role in early childhood development, which is likely to grow further because of continuous expenditures. Mzuzu was chosen for this study because its socio-cultural and educational setting reflects Malawi’s larger backdrop, making it a suitable place to observe children’s transition to primary school.

Research Design

This study used a quantitative method to examine parental and family determinants on children’s transition from community-based childcare centers to public primary school in Mzuzu City, Malawi. A quantitative approach was adopted to get statistical insight into the responsibilities of parents and families during the transition process, allowing for objective measurement of critical elements such as parental participation, support mechanisms, and educational outcomes.

Sampling Framework

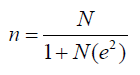

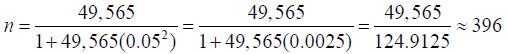

The sample size for this study was determined using Yamane formula, which is acceptable when working with a predetermined population size (Yamane, 1967):

Where:

n = sample size

N = total population (49,565 households in Mzuzu City, according

to NSO, 2018)

e = margin of error (set at 5% for this study)

By applying these values

Thus, the first sample size was determined to be 396 households. To account for anticipated non-responses, the sample size was adjusted to 408 households. A purposive sample approach was used, with Mzuzu City divided into wards. The sample size for each ward was proportional to its population size, ensuring that every household had an equal chance of participating in the study.

Data collection

A standardized household survey questionnaire was used to collect data from parents, guardians, caregivers, and families. The questionnaire included respondent profiles, demographic information, and parents’ involvement in assisting children’s transition from community-based daycare to mainstream public primary schools. It included questions about family involvement, transitional challenges, and parental perceptions of the process.

Data Analysis

The data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) Version 29. Frequencies and percentages were determined and presented as graphs and tables. The influence of numerous factors on children’s transition to primary school was investigated using binary logistic regression with a 95% confidence interval. Variables with extreme confidence intervals and odds ratios (Exp [B]) were removed from the regression model. The results were evaluated using both crude and adjusted odds ratios to provide light on the role of parental and family factors in the transition process.

Ethical Considerations

All ethical protocols were followed in this investigation. Prior to data collection, the Mzuzu University Research and Ethics Committee (MZUNIREC) provided ethical clearance (Ref No: MZUNIREC/ DOR/24/17). Entry into communities from relevant government and local authorities was sought. All participants provided informed consent, ensuring their voluntary involvement. Pseudonyms were employed to hide participant identities, and unique identifying numbers in reports ensured data confidentiality.

Employment Status of Parents as a Determinant Factor in Children’s Transition Process to School

The figure below illustrates the employment status of parents with children aged 3 to 5 years in Mzuzu who are transitioning from Community-Based Childcare Centres (CBCCs) to primary school. It shows that 47.06% of the caregivers (n = 192) were self-employed, 26.72% (n = 109) were unemployed, 25.25% (n = 103) were employed, and only 0.74% (n = 3) were retired. The study observed that parental employment status significantly influences children’s transition from CBCCs to public primary schools in Malawi, as the process is shaped not only by educational factors but also by socio-economic conditions affecting readiness, participation, and continuity in early childhood education. Self-employment, accounting for 47.06% of parents, significantly supported children’s transition to public primary schools due to the flexibility it offered. This flexibility allowed parents to manage their time effectively, accompany children to school, attend parent-teacher meetings, and participate in school readiness activities. These findings align with a study by Munthali, et al. [1] in Malawi, which reported that parents or caregivers engaged in flexible or home-based employment were more likely to participate in CBCC activities. Such involvement enhances children’s readiness for primary school by fostering consistent learning, emotional stability, and stronger communication between caregivers and educators.

Although self-employment may be informal and economically unstable, its time flexibility offers a critical advantage by enabling active parental participation in early childhood development, an essential determinant factor for a successful transition to formal education. However, while employment and self-employment generally support smoother transitions by providing financial and time resources, unemployment presents significant challenges, particularly in low-resource settings such as Malawi. For example, the study observed that unemployed parents often struggle to afford school-related expenses such as uniforms, learning materials, and transportation. This is consistent with UNESCO (2015), which highlights that parental employment significantly influences early childhood education participation and transition outcomes as children from unemployed and underemployed households frequently face barriers such as inadequate school supplies, poor nutrition, and low attendance, all of which hinder school readiness.

Lastly, the findings relate to Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory. In this study, the microsystem encompasses the child’s immediate context, family and CBCCs where parental employment directly affects participation in school readiness activities. The mesosystem, linking home and school, is shaped by self-employed parents’ ability to engage in meetings and support transitions. Likewise, the exosystem includes parents’ employment status, which indirectly impacts the child through economic stability and time availability. Furthermore, the macrosystem reflects broader socio-economic conditions in Malawi, where high unemployment restricts access to educational resources. Finally, the chronosystem captures changes over time, such as the transition from CBCCs to primary school. Thus, parental employment status influences school readiness and transition across all levels of the ecological system.

Parental Education Levels of Children Undergoing the Transition Process

Parental educational attainment significantly influences children’s transition from Community-Based Childcare Centres (CBCCs) to public primary schools. As shown in Figure 2, 52.94% (n = 216) of parents completed secondary education, 31.37% (n = 128) attained tertiary education, 14.22% (n = 58) had primary education only, and 1.23% (n = 5) had no formal education. The high proportion of parents with secondary and tertiary education indicated stronger support for early childhood education compared to those with primary or no formal education. This suggests that parents with higher education levels are more likely to value formal education, understand developmental milestones, and engage in practices that facilitate smooth transitions, including cognitive and socio-emotional development. This aligns with Akwara, et al. [6], who identified maternal education as a key determinant of child well-being and school participation. Similarly, Abuya et al. [37] found that educated caregivers/parents are more involved in school activities, provide educational materials at home, and support consistent school attendance, all critical factors for a successful transition from CBCCs to primary school.

In the Malawian context, Munthali et al. (2008) found that parents with formal education engage more confidently with CBCC caregivers and primary school teachers, promoting continuity in learning. Their literacy skills enable them to respond to school communications and support homework, thereby enhancing school readiness. Additionally, higher educational attainment among caregivers is linked to greater awareness of the benefits of early childhood education and improved ability to navigate the educational system effectively (Efa et al. [38]). However, a key finding from the study revealed that parents with only primary education or no formal education face significant challenges in supporting early learning. They often lack the knowledge, skills, and confidence required to engage effectively with educational institutions and promote school readiness. Murphy, et al. [26] similarly found that low parental education levels limit involvement in school activities, reduce understanding of children’s developmental needs, and hinder support for the transition process. In Malawi, parents/caregivers with limited education face additional challenges in communicating with teachers and understanding the importance of early learning assessments and routines, which negatively impacts children’s preparedness for primary school (Rouse, et al. [7]).

Therefore, the Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory provides a useful lens for understanding how parental education levels influence children’s transition from CBCCs to primary school. In the microsystem, educated parents are more likely to engage directly with their children’s learning, support school readiness, and interact with teachers. Likewise, the mesosystem, which connects home and school, is strengthened when educated parents participate in school activities and maintain communication with educators. The exosystem reflects how parental education, though not directly involving the child affects their developmental context through informed decision- making and provision of learning resources. At the macrosystem level, societal values around education and literacy influence parents’ capacity to support early learning and the chronosystem highlights how parental education shapes long-term attitudes toward schooling, affecting the child’s developmental trajectory. Thus, higher parental education enhances engagement across these systems, facilitating smoother transitions and stronger school readiness.

Income Distribution of Parents of Children Transitioning to Primary School

The income distribution reveals a high prevalence of low-income households, which has significant implications for children’s transition from Community-Based Childcare Centres (CBCCs) to public primary schools. As shown in Figure 3, 54.17% (n = 221) of parents earn less than 90,000 Malawian Kwacha (MWK) per month. Additionally, 24.75% (n = 101) earn between 90,000 MWK and 179,000 MWK, 12.5% (n = 51) between 180,000 MWK and 269,000 MWK, 4.66% (n = 19) between 270,000 MWK and 359,000 MWK, and only 1.72% (n = 7) earn 360,000 MWK or more. The study found that low household income is closely linked to barriers in early childhood education participation and smooth transitions to primary school. Families earning below 90,000 MWK per month often struggled to meet both direct and indirect schooling costs, such as uniforms, learning materials, transportation, and school feeding programs. This aligns with findings by Munthali, et al. [1], who observed that such economic challenges in Malawi frequently lead to delayed school entry or irregular attendance during the transition period. Similarly, Garcia, et al. [10] highlight that poverty limits parents’ capacity to invest in quality early learning, thereby affecting children’s school readiness.

From a positive perspective, households earning above 180,000 MWK per month, though a smaller group (18.88%, n = 77), were better positioned to support their children’s early learning. These parents could afford essential school requirements and actively participated in activities such as pre-primary orientation sessions and parental training provided through CBCCs. This finding aligns with Abuya, et al. [37], who reported that economically stable households in Kenya accessed higher-quality early childhood services and sustained educational support in the early grades. Similarly, Efa et al. [38] found in Ethiopia that higher family income positively correlated with school readiness, attendance, and parental engagement with teachers. Based on these results, it can be concluded, therefore, that Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how household income influences children’s transition from CBCCs to primary school. Within the microsystem, limited income constrains access to essential resources such as learning materials, nutrition, and regular school attendance. The mesosystem, which connects the home and school, is weakened when financial hardship limits parental participation in school-related activities Vise vasa. At the exosystem level, parents’ employment and income indirectly affect the child through reduced economic capacity and time for involvement. The macrosystem reflects Malawi’s broader socio-economic context, where poverty limits investment in early education. Lastly, the chronosystem captures the cumulative impact of income disparities over time, influencing children’s developmental paths and educational outcomes. Overall, income shapes school readiness and transition through these interconnected ecological systems.

Parental Perceptions and Challenges in the Transition of Children to School

Most respondents (85%, n = 347) reported that their children’s transition from CBCCs to primary school was successful, while 15% (n = 61) did not. This high success rate indicates a generally positive perception of the transition process and suggests that CBCCs in Malawi are playing a key role in preparing children for formal education. However, the data also reveal persistent challenges affecting some children’s readiness and adaptation. The most reported issue was difficulty adapting to a new environment (34.31%, n = 140), followed by social challenges with classmates (31.86%, n = 130), academic difficulties (19.61%, n = 80), communication issues with teachers (11.03%, n = 45), and other unspecified challenges (3.19%, n = 13). These findings point to a disconnect between the learning environments of CBCCs and primary schools, particularly in terms of emotional and social adjustment. Similar challenges have been documented in Malawi and other sub-Saharan African contexts, where differences in language of instruction, classroom size, and teaching approaches often hinder smooth transitions (Bwezani, et al. [5]).

Furthermore, parents’ perceptions of the transition process varied, with 59.8% (n = 224) rating it as preparing their children “very well,” 24.02% (n = 98) as “well,” 13.97% (n = 57) as “adequate,” and 1.96% (n = 8) as “poor.” These findings indicate that while most CBCCs effectively equip children with foundational skills for primary education, a notable portion remain only partially successful. This aligns with Greenwood, et al. [13], who found that CBCCs with welltrained staff and strong connections to primary schools better facilitate smooth transitions. Comparative studies in Kenya, Ethiopia, and Uganda indicate that children from pre-primary programs emphasizing play-based learning and school readiness adapt more effectively to primary school’s academic demands (Abuya, et al. [37,38]). These findings underscore the critical role of parental involvement, relevant curricula, and teacher training in facilitating successful transitions. This, therefore, suggests that to improve the transition process, policy and programmatic interventions should prioritize enhancing CBCC service quality, aligning curricula with early primary grades, and implementing structured transition activities such as school visits and orientation sessions. Furthermore, fostering strong partnerships among CBCCs, parents/caregivers, and primary school teachers can support continuity and child adjustment during the initial weeks of schooling.

Parental Roles and Involvement in Facilitating Children’s Transition to Primary School

The findings highlight the significant impact of parental engagement on the effectiveness of early childhood educational transitions, underscoring the essential role parents play in promoting children’s school readiness. A large proportion of parents, 35.29% (n = 144) identified themselves as facilitators of learning and development, while 34.07% (n = 139) regarded themselves as supportive guides and mentors. These self-perceptions indicate a proactive parental approach to early learning and a strong psychological investment in their children’s education. These results align with Abuya, et al. [37], who argue that when parents perceive themselves as integral to their children’s educational journey, they are more likely to adopt practices that foster academic and socio-emotional preparedness, such as language development, positive discipline, and goal setting.

Further evidence of active parental involvement is reflected in the 39.22% (n = 160) of respondents who identified regular communication with teachers as a primary responsibility. This was followed by participation in school events (28.19%, n = 115) and assisting with homework (22.06%, n = 90). These findings are consistent with Clarke, et al. [4], who emphasize that strong parent-teacher partnerships significantly facilitate smoother transitions by harmonizing home and school expectations, particularly in settings where early childhood and primary education curricula are not formally aligned. Regarding the competencies parents deem essential, effective communication skills (36.76%, n = 150) and time management (29.41%, n = 120) emerged as top priorities. This reflects a self-awareness among parents about the importance of managing both time and communication to effectively support their children’s learning. These findings align with UNICEF Malawi (2018), which reported that caregivers equipped with basic parenting skills and knowledge are more likely to engage in consistent and structured transition practices, including school visits, participation in CBCC activities, and the promotion of early literacy.

The high involvement rate, 72.06% (n = 294) of parents reporting being “highly involved” in transition-related activities suggests a strong foundation for developing community-based support systems for early childhood development (ECD) in Malawi. This finding aligns with Lynch, et al. [16], who emphasize that successful transitions are more likely in communities where parents are not only well-informed but also actively participate in decision-making processes related to ECD programs. Despite the overall positive levels of engagement, a minority of parents identified themselves as passive observers (14.95%, n = 61), with a very small proportion (0.49%, n = 2) reporting minimal involvement. This suggests gaps in outreach and empowerment efforts. The presence of such parents may reflect barriers related to limited access to information, socio-economic constraints, or cultural norms that discourage active participation in education. As Garcia, et al. [10] observe, such disparities are common in sub-Saharan Africa, where parents, particularly those with lower educational attainment or language barriers often lack confidence or do not feel welcomed in school settings.

Moreover, only 10.54% (n = 43) of parents identified “encouraging social interactions with classmates” as a key responsibility, indicating a limited awareness of the role peer relationships play in supporting children’s emotional and social adjustment to primary school. Efa, et al. [38] emphasize that while academic readiness is important, the ability to form secure social bonds is equally critical for a successful school experience. Lastly, 3.92% (n = 16) of parents reported neutrality indicating a need for enhanced parent training, sensitization efforts, and inclusive transition programs for awareness regarding their involvement. As UNESCO (2015) advocates, effective transition models should engage parents not merely as observers but as active collaborators in planning and implementing early education pathways. These findings, therefore, highlight the importance of policy and programmatic strategies that strengthen parental awareness, build parenting competencies, and promote inclusive partnerships among families, CBCCs, and primary schools.

Parental and Family Influences on Children’s Transition to Primary School

The data provide important insights into the influence of family dynamics, contextual factors, and parental involvement on children’s transitions from Community-Based Childcare Centres (CBCCs) to public primary schools in Malawi. A majority of respondents (61.52%) described their family environment as “supportive and cohesive,” with an additional 21.57% reporting it as “somewhat supportive.” This suggests that over 83% of families offer an emotionally and relationally stable home environment, an important determinant factor in facilitating smooth educational transitions. Therefore, it can be argued that supportive family settings contribute to children’s emotional security, consistent routines, and encouragement for learning, which are essential for fostering resilience and confidence as they adapt to the demands of formal schooling. This finding aligns with Sunny, et al. [18], who emphasize the family’s role as the primary agent in promoting early childhood development and successful transitions to primary education in Malawi. They argue that families providing a nurturing environment are more likely to offer emotional and practical support, thereby facilitating children’s smoother adaptation to the social and cognitive demands of school.

Although most respondents reported supportive family environments, a small proportion indicated “somewhat challenging” (1.47%) or “challenging” (0.98%) family dynamics. Despite their low prevalence, these conditions can significantly impede children’s school readiness, particularly when conflict, instability, or emotional neglect are present. Garcia, et al. [10] note that children from unstable family backgrounds often exhibit diminished cognitive and socio-emotional preparedness for formal education. Similarly, Majamanda, et al. [33] found that in Malawi, children from families facing economic hardship or parental absence frequently miss essential early learning opportunities, increasing their risk of poor school adaptation. Furthermore, respondents identified family structure and composition (36.76%), sibling dynamics (31.86%), and parental work schedules (15.93%) as key family-related determinants influencing transitions, with financial considerations also noted (15.44%). These findings indicate that broader contextual factors significantly shape children’s transition experiences. For instance, extended family structures common in Malawi can serve as both support and strain. Sibling care responsibilities may limit the time older children or parents can dedicate to early education activities, while irregular or inflexible work schedules may hinder consistent parental engagement. These dynamics are consistent with Kholowa [27], who found that socio-economic conditions and family structures in Malawi restrict parental involvement in early education, particularly among low-income and rural households.

Lastly, the most notable finding is that 74.51% of respondents reported being “actively involved in all aspects including attending school meetings, paying school funds, learning materials, visit the teaching process among other” of their child’s primary education, while 21.81% were involved in “specific areas of interest such as payment of school development fees and learning materials.” This indicates a high level of parental commitment, which is strongly linked to improved school readiness, smoother transitions, and better learning outcomes. This aligns with UNICEF (2018) and Neuman et al (2014) emphasis that comprehensive parental engagement significantly enhances children’s confidence, emotional preparedness, and learning consistency. In Malawi, Mphweya, et al. [39] found that children with regularly involved parents adapted more effectively to formal education and faced a lower risk of early dropout. Conversely, the small minority of parents who reported being “minimally involved” (2.7%) or “not involved” (0.49%) raise concerns. Although numerically limited, such disengagement can disproportionately hinder children’s adaptation, especially in homes lacking compensatory educational support. Therefore, addressing these gaps requires a multifaceted approach, including policy frameworks that enhance parental education, promote workplace flexibility, and strengthen community support mechanisms to improve transition outcomes.

Parental Participation and Communication in Supporting Children’s Transition to Primary School

The high levels of parental participation and communication observed in the data align with existing literature, underscoring their crucial role in supporting children’s readiness and adjustment during early formal schooling. Notably, 87.25% of parents reported attending parent-teacher meetings, reflecting strong engagement with the school environment. Additionally, 54.17% volunteered at school events, while smaller proportions participated in parent committees (21.57%) and school workshops (20.1%). These findings indicate that many parents actively contribute to the school community, albeit often in relatively passive roles. Epstein’s (1995) Framework of Parental Involvement highlights that such participation, especially volunteering and governance bridges the home-school gap, fosters shared responsibility for learning, and enhances continuity between pre-primary and primary education. Research from the Malawian context corroborates these findings. McLinden, et al. [30] observed that parental involvement in school governance and activities significantly enhanced student attendance and school readiness, particularly during the transition to primary school. Similarly, Lynch [16] emphasized that parental presence at school-related events predicted successful transitions, especially in rural areas where CBCCs are foundational. Comparable evidence from Uganda by Mfum [40] demonstrated that parental participation in school events and decision- making fostered a collective sense of ownership and accountability, thereby improving the quality of early learning transitions.

However, the relatively low engagement in school governance activities, such as participation in parent committees and workshops, indicates a potential limitation in current parental involvement models. This restricted participation may reflect parents’ lack of empowerment, confidence, or opportunity, particularly in under-resourced communities. Consequently, many parents remain confined to observational roles, limiting their potential as co-educators and decision- makers in their children’s education. Additionally, the findings indicate a predominantly positive pattern of intra-family communication, with 80.39% of respondents reporting open and frequent discussions about their children’s education. This is consistent with Mphweya, et al. [39] who found that children from Malawian households engaging in regular educational conversations exhibited greater confidence and preparedness for school routines. Similarly, Ngwaru (2014) documented comparable effects across East and Southern Africa, where strong home communication practices were linked to improved school attendance and early grade engagement. UNESCO (2015) further emphasizes the significance of family-school dialogue in aligning home and school cultures, thereby fostering a more cohesive educational environment for young learners. Despite this positive trend, a minority of families, approximately 17.16% reported communicating only as needed, while 1.47% indicated limited communication. These gaps are associated with lower parental literacy, economic constraints, and social barriers that hinder consistent engagement. Consequently, children in such households may lack the emotional and cognitive support necessary to successfully navigate the challenges of transitioning to formal education, particularly in contexts of existing vulnerability and marginalization. Crucially, a significant majority (91.67%) of respondents affirmed that effective communication positively influenced their child’s transition to primary school, while only 2.21% reported no perceived benefit.

This consensus underscores a broad recognition among parents that communication, both within the family and between home and school enhances children’s capacity to adapt to new learning environments, respond constructively to feedback, and establish trusting relationships with teachers. Evidence from African contexts supports these findings. In other study, Musendo, et al. [19] found that children whose parents engaged in regular communication with teachers adjusted more readily to school routines and expectations. Similarly, Pewa [41] reported that collaborative communication practices in South Africa contributed to reduced dropout rates and absenteeism in the early grades. Therefore, addressing communication gaps in the minority of households remains critical to ensuring that no child is disadvantaged by preventable barriers. Policymakers and educators should promote inclusive, accessible engagement strategies, including the use of local languages and community-based training. Initiatives such as UNICEF Malawi’s “Let’s Chat ECD” offer promising models for scaling communication and strengthening parenting capacity.

Determinants of Family Decision-Making During Educational Transitions of Children

A large majority of respondents (88.48%) reported that external influences or advice informed their decision-making during their child’s transition to primary school. This finding indicates that many families operate within social networks including teachers, other parents, and community leaders that significantly shape educational choices. These results are consistent with Munthali, et al. [1], who observed that such networks in rural Malawi, particularly those involving CBCC facilitators, positively influenced parental perceptions of schooling. Similarly, Banda, et al. [31] found that teacher recommendations and community guidance played a crucial role in helping rural parents navigate enrollment processes and mitigate anxieties related to formal education. Additionally, parental strategies to support their children’s transition reflect a complex form of engagement. The most reported actions were effective communication with teachers (36.76%) and active involvement in school-related activities (28.19%). Assisting with academic challenges (20.83%) and providing emotional support (13.97%) were cited less frequently but remain significant. These patterns align with findings by Mphweya, et al. [39], who observed that open communication and consistent parental presence enhanced school readiness and emotional adjustment among Malawian children. Similarly, research by Komba and Mwandanji [42] in Tanzania demonstrated that parental involvement in classroom activities and teacher interactions facilitated smoother transitions, particularly for children in resource-constrained settings. However, the comparatively lower levels of reported emotional support and academic assistance may reflect gaps in parental capacity or confidence, especially within low-literacy or economically marginalized households. This challenge is prevalent in Malawi, where disparities in parental educational attainment and limited access to parenting resources persist (Banda, et al. [31]).

These findings underscore the need for targeted interventions that strengthen parents’ ability to support both academic development and children’s emotional preparedness for school. Furthermore, in terms of decision-making influences, 49.02% of respondents identified teacher recommendations, while 31.86% cited advice from other parents. In contrast, the educational philosophy of the school (12.25%) and financial considerations (6.86%) played a comparatively minor role. These findings suggest a strong reliance on interpersonal rather than institutional or financial factors, potentially reflecting limited access to formal information or structured guidance on school selection. This pattern aligns with findings from Mfum [40] in Uganda, who noted that parental decisions around school transitions were often shaped by trusted local networks rather than formal education policies or curricular frameworks. Similarly, Chimombo, et al. [43] observed that rural families in Malawi typically selected schools based on proximity and community advice rather than pedagogical quality or academic philosophy.

Overall, external guidance, particularly from teachers and peers continues to play a significant role in shaping family decisions regarding school transitions. While many parents engage actively, especially through communication with educators, more intensive forms of involvement such as providing academic support and participating in school governance remain limited. To bridge these gaps, policymakers and development practitioners should prioritize the expansion of family engagement initiatives. These may include community radio programs, parenting workshops, and localized peer-learning networks. Additionally, strengthening teacher-parent communication, delivering parental education in local languages, and establishing inclusive forums for parental participation in school governance can promote more comprehensive and equitable transition experiences for all children. Therefore, Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory provides a comprehensive framework for interpreting parental perceptions and challenges in children’s transition from CBCCs to primary school. At the microsystem level, direct interactions between children, parents, and teachers shape the transition experience.

Additionally, high parental involvement such as attending meetings and maintaining communication strengthens this immediate environment, fostering successful adaptation. However, challenges like difficulty adapting or social issues highlight tensions within this system. The mesosystem emphasizes the connections between home and school, which are evident in parents’ active roles as facilitators, mentors, and participants in school activities. Whereas strong mesosystem linkages improve continuity and support during the transition. The exosystem includes broader factors such as parental work schedules and external advice that indirectly influence children’s experiences by affecting parental availability and decision-making. At the macrosystem level, cultural values, economic conditions, and educational policies impact parental roles and the quality of CBCCs and primary education, framing the environment in which transitions occur. Finally, the chronosystem captures changes over time, such as evolving family dynamics and parental skills, which influence the child’s developmental trajectory and school adjustment. Thus, Bronfenbrenner’s theory highlights the complex, multi-layered influences on children’s transition, underscoring the importance of integrated support across systems to enhance educational outcome.

This study, grounded in Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, explored the influence of family, educational, and socioeconomic determinant factors on children’s transitions from Community-Based Childcare Centres (CBCCs) to formal primary schooling in Malawi. The microsystem comprising parental education, income, and employment was found to directly affect children’s readiness for school. The mesosystem, characterized by parental interactions with teachers and participation in school-related activities, also played a supportive role in facilitating smoother transitions. However, the absence of a statistically significant relationship between parental participation and successful transitions challenges traditional models that emphasize parental agency and household structure as primary predictors of educational success. Instead, the findings support an interactionist perspective, suggesting that transitions are shaped collaboratively by families, educators, and community networks. Additionally, external influences, particularly teacher recommendations and advice from other parents, emerged as critical in guiding family decision-making during the transition period. This highlights the importance of contextual and relational factors beyond the immediate household, indicating that community dynamics and institutional support mechanisms are more influential than previously assumed. At the same time, while supportive family relationships remain important, they are not sufficient on their own to ensure a successful transition to primary school. Therefore, to address these challenges, it is essential to strengthen community engagement to raise awareness about the importance of timely school enrolment and early education [44-55].

Furthermore, economic empowerment interventions such as vocational training and access to microfinance may help alleviate financial barriers that hinder school readiness as schools adopt proactive strategies to involve parents, including structured workshops and regular communication, to foster stronger home-school relationships and support children’s adjustment to the formal school environment. Likewise, education policies must embrace a holistic approach that integrates transition programs, school readiness initiatives, and inclusive community engagement tailored to families from diverse backgrounds meaning that schools should recognize that different forms of parental involvement yield varying impacts and provide targeted guidance to caregivers. Hence, ensuring communication through clear, culturally sensitive channels can further encourage meaningful participation. Finally, as teachers play a vital role in shaping parental decisions, they should be equipped to offer continuous support during the transition process to strengthening collaboration among schools, families, and community actors through mentorship programs and peer-support initiatives to improve education transition outcomes in Malawi.