Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Hatadani Shunsuke1 and Yasuko Kawahata2*

Received: April 17, 2025; Published: August 13, 2025

*Corresponding author: Yasuko Kawahata, 3-34-1 Nishi-Ikebukuro, Toshima-ku, Tokyo, 171-8501, JAPAN

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2025.61.009640

Creating Informational Health through the Interaction of True and Socially Expressed Opinions

In contemporary society, understanding the processes of opinion formation and their interactions is extremely important for social consensus building, policy decisions, and the health of everyday communication. This paper focuses on Ishii et al.’s opinion dynamics model, which has made significant contributions to the mathematical understanding of opinion formation. By explicitly incorporating the dual structure of “true opinions” (honne) and “socially expressed opinions” (tatemae), which is particularly evident in Japanese society, we can construct a communication model that more closely reflects reality. In Japanese, “honne” refers to one’s true opinions and feelings that exist internally, while “tatemae” refers to opinions and attitudes expressed externally in con- sideration of social context and interpersonal relationships. This duality is not simply falsehood or deception but functions as cultural wisdom for balancing social harmony and individual autonomy. However, social consensus formed without adequate understanding of this dual structure may accumulate potential conflicts and dissatisfactions beneath a superficial harmony, risking social division and collapse of trust in the long term. In this paper, we propose an extension of Ishii et al.’s trust-distrust model in which each agent maintains two internal states: “true opinion” and “socially expressed opinion.” This extension enables more detailed analysis of opinion formation processes under the influence of social pressure, power structures, and group norms. Particularly noteworthy are the conversion mechanisms between “true” and “socially expressed” opinions and how they influence group-level consensus formation and conflict resolution.

Informational Health and Communication Integrity

The increasing complexity and diversification of information environments in modern society significantly influence individual opinion formation. In environments where vast amounts of information are shared instantaneously, the quality and reliability of information, as well as the recipient’s information processing ability, are being questioned, highlighting the importance of the concept of “Informational Health.” Informational health refers to the state in which individuals and groups can make rational judgments and decisions based on appropriate information, and it can be considered a basic element of modern well-being alongside physical and mental health.

An opinion dynamics model that explicitly considers the dual structure of true and socially expressed opinions provides important insights for achieving informational health. Appropriate balance between maintaining social harmony (tatemae) and expressing genuine individual opinions (honne) can promote informational health in the following ways:

• Substantiation of social consensus: Enabling consensus formation that properly considers diverse true opinions rather than merely superficial agreement.

• Visualization and resolution of potential conflicts: Recognizing the differences in true opinions hid- den behind socially expressed ones, creating opportunities for mutual understanding through dialogue.

• Improving communication transparency: Better understanding of the intentions and contexts of statements through explicit recognition of the relationship between true and socially expressed opinions.

• Diversification of information selection: Promoting learning from diverse information sources through recognition of people with different true opinions.

Grassroots Co-creation of Informational Health

Achieving informational health requires not only top-down information regulation and media literacy education but also grassroots efforts through interactions in daily communication between individuals. The opinion dynamics model proposed in this paper, which considers true and socially expressed opinions, provides clues to understand the mechanisms of such grassroots co-creation of informational health.

Specifically, the following mechanisms for grass- roots informational health creation can be considered:

• Creating Safe Spaces for Expressing True Opinions: It is important to form environments where people can express their true opinions and deepen mutual understanding with adequate psychological safety rather than complete anonymity. In simulations, such environments can be modeled by appropriate setting of the trust parameter dij .

• Promoting Contextual Understanding of Socially Expressed Opinions: Enhancing the ability to more accurately infer the true opinions and intentions behind socially expressed ones by deepening the understanding that expression through socially acceptable means is not simply falsehood but contains specific social contexts and considerations. This is expressed by adjusting the parameters α and β in the sigmoid function.

• Utilizing Meta-Communication: Promoting dialogue about the nature of communication itself (meta-communication) to provide opportunities for parties involved to adjust the appropriate balance between true and socially expressed opinions. This can be expressed as an extension of the function F (t, i, c, A, m) in the model.

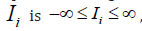

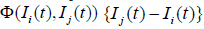

• Securing Diverse Opinion Expression Channels: Allowing different

expression forms (direct and indirect) in the same venue,

enabling flexible opinion expression according to situations and

contexts. This is expressed as a diversification of the conversion

function  between true and socially expressed

opinions. These efforts can potentially lead to a cyclical improvement

of informational health by interacting with each other. For

example, an increase in safe spaces for expressing true opinions

can promote contextual understanding of socially expressed

opinions, which in turn enhances the quality of meta-communication,

leading to more effective use of diverse opinion expression

channels.

between true and socially expressed

opinions. These efforts can potentially lead to a cyclical improvement

of informational health by interacting with each other. For

example, an increase in safe spaces for expressing true opinions

can promote contextual understanding of socially expressed

opinions, which in turn enhances the quality of meta-communication,

leading to more effective use of diverse opinion expression

channels.

This paper provides a detailed analysis of the consensus formation model developed by Ishii et al., examining its fundamental characteristics. Ishii et al.’s model is a kind of multi-state Ising model that can evaluate agreement and disagreement with infinite granularity [1,2]. However, comparisons of some parameters within the model are insufficient, and their functional meanings are not adequately explained. This paper aims to re-examine this model and provide a detailed analysis of its basic properties.

The consensus formation model developed by Ishii et al. is a type of multi-state Ising model that can evaluate agreement and disagreement with infinite granularity. Ishii et al.’s research demonstrates the basic characteristics of opinion consensus formation in dyads, tri- ads, and medium-sized groups1) [3]. However, com- parisons of some constant parameters are lacking, and their functional meanings are not addressed. This paper aims to review Ishii et al.’s consensus formation model and examine its basic characteristics in detail. Research on opinion dynamics has been approached previously using methods based on sociophysics and statistical physics [4,5]. A new approach to understanding sociological collective behavior based on the framework of critical phenomena in physics began when it was first proposed that constructing a simple mean-field approximation model to apply to the strike process in social factories would be the first step [6].

Ishii’s Opinion Dynamics Theory

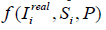

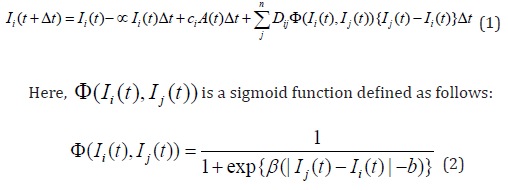

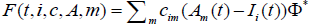

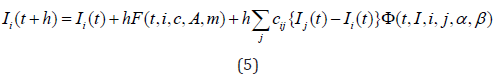

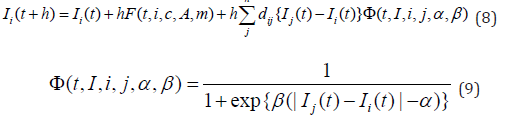

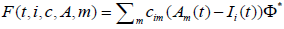

From the literature [1,3], the change in opinion is expressed by the following equation:

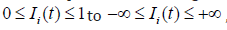

Equation (1) represents how opinions change due to the influence

of others. First, the range of  , with Ii being

positive for affirmative opinions, negative for negative opinions, and

Ii = 0de- fined as a neutral opinion. The second term on the right side

of equation (1) is a forgetting term, which discards part of one’s current

opinion to update it. The third term on the right side represents

influences received from sources other than dialogue, such as media

[7,8]. A(t) represents influence, and the coefficient i c is set individually

as susceptibility to influence (Figure 1).

, with Ii being

positive for affirmative opinions, negative for negative opinions, and

Ii = 0de- fined as a neutral opinion. The second term on the right side

of equation (1) is a forgetting term, which discards part of one’s current

opinion to update it. The third term on the right side represents

influences received from sources other than dialogue, such as media

[7,8]. A(t) represents influence, and the coefficient i c is set individually

as susceptibility to influence (Figure 1).

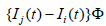

The  in the fourth term on the right side is a sigmoid

function expressed by equation (2), which becomes smaller as

the difference in opinions between two agents becomes larger. The

value of

in the fourth term on the right side is a sigmoid

function expressed by equation (2), which becomes smaller as

the difference in opinions between two agents becomes larger. The

value of  becomes small when opinions

are too close (small difference in opinions) and also when opinions

are too far apart (large difference in opinions). The coefficient Dij

is defined as “trust toward the other party,” with a larger value indicating

more trust in the target and a smaller value indicating distrust

[9,10]. Overall, equation (1) expresses the idea that “one’s opinion

changes under the influence of people whose opinions are moderately

different from one’s own, as well as media, etc.”

becomes small when opinions

are too close (small difference in opinions) and also when opinions

are too far apart (large difference in opinions). The coefficient Dij

is defined as “trust toward the other party,” with a larger value indicating

more trust in the target and a smaller value indicating distrust

[9,10]. Overall, equation (1) expresses the idea that “one’s opinion

changes under the influence of people whose opinions are moderately

different from one’s own, as well as media, etc.”

Questions on Ishii’s Opinion Dynamics Theory

Having explained the equation for opinion change, there are several

questions about these equations. First, regarding the validity of

the second and third terms on the right side of equation (1). Considering

the second term, in the case where there is no influence from

sources other than conversation, that is, when  , and

when all participants in the dialogue agree and each person’s opinion

value is approximately the same, equation (1) becomes monotonically

decreasing and converges to 0. While this seems natural just

looking at the equation, it is unlikely that opinions naturally become

neutral simply due to not being exposed to a topic/agenda for a sufficient

amount of time (although there is room to consider changes in

opinion due to sudden mutations or changes in values, this is beyond

the scope of this paper) (Figure 2). Also, while there is no explanation

in the literature [1], it can be inferred from the graph that α = 0 ,

implicitly indicating that “opinions do not naturally become neutral.”

Thus, it is considered that the second term

, and

when all participants in the dialogue agree and each person’s opinion

value is approximately the same, equation (1) becomes monotonically

decreasing and converges to 0. While this seems natural just

looking at the equation, it is unlikely that opinions naturally become

neutral simply due to not being exposed to a topic/agenda for a sufficient

amount of time (although there is room to consider changes in

opinion due to sudden mutations or changes in values, this is beyond

the scope of this paper) (Figure 2). Also, while there is no explanation

in the literature [1], it can be inferred from the graph that α = 0 ,

implicitly indicating that “opinions do not naturally become neutral.”

Thus, it is considered that the second term  in equation (1)

should not exist.

in equation (1)

should not exist.

Next, consider the third term of equation (1) [11]. Similarly to

the previous discussion, when all participants in the dialogue agree

and each person’s opinion value is approximately the same, taking

the previous argument into account, equation (1) becomes a function

dependent on  . This means that opinions change only by the

amount of external influence, and if

. This means that opinions change only by the

amount of external influence, and if  diverges to infinity,

and if

diverges to infinity,

and if  diverges to negative infinity. Such patterns

might occur when considering unique patterns like extremists [12].

However, generally speaking, it is natural to think that even external

forces like media have certain opinions [13], and that in cases where

one is only influenced by and follows them, opinion values converge

to a certain value rather than diverging infinitely, aligning with that

external force (Table 1).

diverges to negative infinity. Such patterns

might occur when considering unique patterns like extremists [12].

However, generally speaking, it is natural to think that even external

forces like media have certain opinions [13], and that in cases where

one is only influenced by and follows them, opinion values converge

to a certain value rather than diverging infinitely, aligning with that

external force (Table 1).

Second, the issue is that constants set in equations (1) and (2) have not been given meanings. Specifically, these are α in equation (1) and β, b in equation (2) [3]. For α, based on the previous discussion, decay coefficient or forgetting coefficient would be appropriate, but this remains speculative without explicit docu- mentation. As for β, b in equation (2), the method for setting each value is not specified, making them determined by the researcher’s discretion. While this is not necessarily bad in itself, I question the appropriateness of settling for researcher discretion when investigating basic properties (Figure 3).

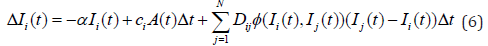

Improved Opinion Dynamics Theory

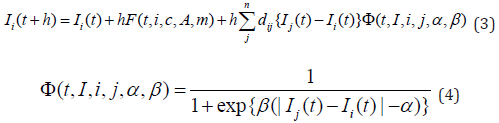

Based on the contents up to the previous section, equations (1) and (2) are improved as follows [14]:

i, j each represent agents, which are elements of the analyzed set n

[15]. Also, n is a subset of the entire society N, and i, j ∈ n ⊂ N. The forgetting

term  in equation (1) has been deleted, and the influence

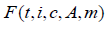

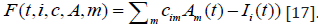

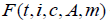

from sources other than dialogue has been set as F(t,i,c, A,m)

[16]. Regarding the function F, m represents the source such as TV

or social media, A represents the opinion value of the source, and c

represents the influence agent I receive from source m. If we were

to model this after equation (1), function F could be expressed as

in equation (1) has been deleted, and the influence

from sources other than dialogue has been set as F(t,i,c, A,m)

[16]. Regarding the function F, m represents the source such as TV

or social media, A represents the opinion value of the source, and c

represents the influence agent I receive from source m. If we were

to model this after equation (1), function F could be expressed as

. Also, considering the

condition mentioned earlier that “when only influenced by and following

external forces, values con- verge to a certain value, and when

not following, they converge after maintaining a certain distance,” F

could be expressed as

. Also, considering the

condition mentioned earlier that “when only influenced by and following

external forces, values con- verge to a certain value, and when

not following, they converge after maintaining a certain distance,” F

could be expressed as  [18]. Note that Φ∗ is a sigmoid function that operates between external

force m (such as social media) and agent i . The sigmoid function

defined in equation (2) has been changed to equation (4) for improved

readability. Also, to prevent confusion with β, b in equation (2)

has been changed to α [19].

[18]. Note that Φ∗ is a sigmoid function that operates between external

force m (such as social media) and agent i . The sigmoid function

defined in equation (2) has been changed to equation (4) for improved

readability. Also, to prevent confusion with β, b in equation (2)

has been changed to α [19].

In the previous section, α, β were given as arbitrary constants,

but I am skeptical of this approach [20]. It is obvious that even with

the same  , Φ takes different values if α, β are different. While

this might not be problematic if treated simply as a function, since Φ

is a function with the meaning that “one is less influenced by another’s

opinion the more distant it is from one’s own,” α, β should not be

constants without specific meanings [21]. In equations (1) and (3),

the influence from another’s opinion is given as

, Φ takes different values if α, β are different. While

this might not be problematic if treated simply as a function, since Φ

is a function with the meaning that “one is less influenced by another’s

opinion the more distant it is from one’s own,” α, β should not be

constants without specific meanings [21]. In equations (1) and (3),

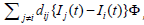

the influence from another’s opinion is given as  ,

and

,

and  represents “the strength and direction of influence

given according to the difference in opinion with the other” [22]. The

“direction of influence” is given according to the relationship with the

other’s opinion value, and the direction of agent i’s approach to or

repulsion from agent j for 0 ij d > is shown in Table 2.

represents “the strength and direction of influence

given according to the difference in opinion with the other” [22]. The

“direction of influence” is given according to the relationship with the

other’s opinion value, and the direction of agent i’s approach to or

repulsion from agent j for 0 ij d > is shown in Table 2.

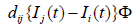

Now,  represents ”trust in the other (agent j)”

from agent i’s perspective and ”the strength and direction of influence

given according to the difference in opinion with the other (agent j),”

but when considering dialogue with only socially ex- pressed opinions,

it is more natural to think of ij d not as “trust that agent i has

for agent j itself” but as ”the degree of consensus between agent j’s

opinion and social norms as seen by agent i” [23]. Therefore, I define

“the degree of consensus between agent j’s opinion and social norms

as seen by agent i” as cij , and the following equation reflects this in

equation (3) [24]:

represents ”trust in the other (agent j)”

from agent i’s perspective and ”the strength and direction of influence

given according to the difference in opinion with the other (agent j),”

but when considering dialogue with only socially ex- pressed opinions,

it is more natural to think of ij d not as “trust that agent i has

for agent j itself” but as ”the degree of consensus between agent j’s

opinion and social norms as seen by agent i” [23]. Therefore, I define

“the degree of consensus between agent j’s opinion and social norms

as seen by agent i” as cij , and the following equation reflects this in

equation (3) [24]:

This is simply replacing d in equation (3) with c, but its meaning

differs from equation (3) [25]. Specific meanings should also be given

to the parameters α, β in the sigmoid function?). Let’s first consider

parameter α. Since  in equation (4) is “(difference in

opinion values) - α,” α needs to be a parameter related to opinion values.

When

in equation (4) is “(difference in

opinion values) - α,” α needs to be a parameter related to opinion values.

When  , the sigmoid function takes 0.5, which is

an inflection point, so it would be reasonable to consider α as a kind

of threshold?) (Figure 4).

, the sigmoid function takes 0.5, which is

an inflection point, so it would be reasonable to consider α as a kind

of threshold?) (Figure 4).

Proposal of the Trust-Distrust Model

To reflect more realistic social situations, Ishii et al. extended the conventional bounded confidence model and proposed the “Trust-Distrust Model” [1,2]. The characteristics of this model are as follows:

• Expansion of opinion value range: Extended from the conventional

, allowing positive values to

represent affirmative opinions and negative values to represent

negative opinions.

, allowing positive values to

represent affirmative opinions and negative values to represent

negative opinions.

• Introduction of trust coefficient signs: Redefined coefficient ij D as a trust coefficient, with Dij > 0 representing a trust relationship and Dij < 0 representing a distrust relationship.

• Introduction of sigmoid function: Introduced sigmoid function

to limit the influence when the difference in opinions

is very large or small.

to limit the influence when the difference in opinions

is very large or small.

• Consideration of mass media influence: Introduced the term

to represent influence from external information (such as

mass media).

to represent influence from external information (such as

mass media).

• Consideration of interest decay: Introduced the term  to

represent the decline in interest over time.

The basic equation of the Trust-Distrust model incorporating

these features is expressed as follows:

to

represent the decline in interest over time.

The basic equation of the Trust-Distrust model incorporating

these features is expressed as follows:

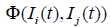

This sigmoid function changes smoothly around  and

rapidly approaches 0 when the difference in opinions between two

people exceeds the threshold b, enabling the expression of the realistic

situation where “one is hardly influenced by people whose opinions

are too different” [14]. Also, the term

and

rapidly approaches 0 when the difference in opinions between two

people exceeds the threshold b, enabling the expression of the realistic

situation where “one is hardly influenced by people whose opinions

are too different” [14]. Also, the term  expresses the

property that one is not influenced by people with the same opinion

as oneself (Figure 5).

expresses the

property that one is not influenced by people with the same opinion

as oneself (Figure 5).

Questions and Improvements on Ishii’s Opinion Dynamics Theory

While Ishii et al.’s model has excellent features, there are also several questions [14]. This paper focuses particularly on the following points:

• Validity of the forgetting term: The term  in equation

(6) means that opinions naturally converge to neutral (0) in the

absence of external influence, which may not align with realistic

human opinion formation processes.

in equation

(6) means that opinions naturally converge to neutral (0) in the

absence of external influence, which may not align with realistic

human opinion formation processes.

• Validity of the external influence term: The term  alone in

equation (6) allows opinions to potentially diverge to infinity if

external influence continues, which is unrealistic.

alone in

equation (6) allows opinions to potentially diverge to infinity if

external influence continues, which is unrealistic.

• Ambiguity in parameter settings: The meanings and setting methods for parameters such as α, β, and b are not clearly defined. To address these questions, this paper has improved the model as follows:

The main improvements are as follows:

• Deletion of the forgetting term: Deleted  from equation

(6) to create a more realistic model.

from equation

(6) to create a more realistic model.

• Redefinition of external influence: Generalized external influence

as function  to solve the divergence problem. In

particular, forms such as

to solve the divergence problem. In

particular, forms such as  can be considered, resulting in a model where opinions converge

to a certain value.

can be considered, resulting in a model where opinions converge

to a certain value.

• Clarification of parameters: Clearly defined parameter α in the sigmoid function as a threshold for opinion difference, and defined β as a function that varies according to trust in the other party.

• Redefinition of trust degree: Changed the interpretation of dij from “trust in the agent itself” to “the degree of consensus between the agent’s opinion and social norms,” modeling more realistic human relationship dynamics.

One’s “True Opinion,” Others’ “Socially Ex- pressed Opinions,” Superficial Trust Relation- ships, and Social Pressure: Discussion in the Model

Here, Freal is the opinion update function at the “true opinion” level, which is updated mainly based on others’ “true opinions” and true trust relationships. On the other hand, Fformal is the opinion update function at the ”socially expressed opinion” level, which is updated based on one’s own ”true opinion,” others’ ”socially expressed opinions,” superficial trust relationships, and social pressure P. Equations (10) and (11) are the core equations of the model proposed in this paper, which explicitly considers the dual structure of ”true” and ”socially expressed” opinions (Figure 6).

Informational Health and Consensus Formation Model Considering the Dual Structure of True and Socially Expressed Opinions: Here, we analyze simulation results of a consensus formation model that explicitly incorporates the dual structure of “true and socially expressed opinions” that is particularly evident in Japanese society, extending Ishii et al.’s Trust-Distrust model. From the results of simulations using five different parameter sets, we consider the relationship between informational health and opinion formation processes, as well as the influence of social factors.

Creation of Informational Health through the Interaction of True and Socially Expressed Opinions: The dual structure of true and socially expressed opinions has functioned as cultural wisdom for balancing social harmony and individual autonomy, rather than mere falsehood or deception. The simulation results mathematically express how the dynamics of this dual structure affect informational health.

From the simulation results, particularly important findings include:

• In Simulation 4, the divergence between true and socially expressed opinions is minimal (0.007), while informational health maintains a high level (0.732). This simulation is characterized by a relatively high influence from socially expressed to true opinions (0.178) and a low true opinion update rate (0.107). This result shows that not only do socially expressed opinions approach true ones, but true opinions are also pulled toward socially expressed ones, resulting in increased consistency between the two (Figure 7).

• In Simulation 5, the divergence between true and socially expressed opinions is maximal (0.145), while the average informational health is also lowest (0.311). This result mathematically supports that divergence between true and socially expressed opinions negatively affects informational health.

• In Simulation 2, the average informational health is the highest (0.813), with moderate social pressure (0.475). This suggests that neither excessive social pressure nor excessive individualism promotes informational health (Figure 8).

Relationship Between Social Pressure and Informational Health

Way to Informational Symbiosis: The simulation results provide important insights into the relationship between social pressure (P) and informational health. As shown in Table 3, in Simulation 1 with the highest social pressure (0.735), informational health is moderate (0.753), whereas in Simulation 2 with moderate social pressure (0.475), informational health is highest (0.813). In contrast, in Simulation 3 with relatively low social pressure (0.192), informational health maintains a good level (0.739).

These results suggest the following non-linear relationship between social pressure and informational health:

• Excessively high social pressure may decrease informational health by promoting excessive conformity to socially expressed opinions, widening the gap from true opinions.

• Moderate social pressure may promote balanced opinion formation by encouraging a certain consideration for socially expressed opinions while also allowing expression of true opinions, thereby enhancing informational health.

• Even when social pressure is relatively low, a certain convergence of opinions may occur through interactions between agents, potentially maintaining informational health.

• Particularly noteworthy are the results of Simulation

• In this simulation, despite moderate social pressure (0.429), the influence from true to socially expressed opinions is lowest (0.107), creating a large divergence between true and socially expressed opinions and significantly reducing informational health. This indicates that not only the absolute magnitude of social pressure but also the pattern of interaction between true and socially expressed opinions has a significant impact on informational health (Table 4).

Path to Informational Symbiosis: When integrating the simulation results, the possibility of a new social practice that could be called “Informational Symbiosis” emerges, based on informational health. This refers to a state where individual informational health and healthy group consensus formation mutually support and strengthen each other (Figure 9).

Characteristics of informational symbiosis include:

• Appropriate Balance Between True and Socially Expressed Opinions: As in Simulations 2 and 4, a state where there is appropriate interaction between true and socially expressed opinions without extreme divergence (Table 5).

• Dynamic Balance Between Diversity and Convergence: A process where initial diversity of opinions is respected, yet a certain convergence occurs over time.

• Mutual Creation of Informational Health: A virtuous cycle where individual informational health improves through interaction with others, which in turn improves the information environment for the entire group.

• Natural Suppression of Aggressive Communication: A state where the motivation for aggressive expression is reduced, and healthy dialogue is promoted by maintaining an appropriate balance between true and socially expressed opinions.

Simulation 4 is considered closest to the ideal state of informational symbiosis. In this simulation, the di- vergence between true and socially expressed opinions is minimal, and informational health maintains a high level. Additionally, the process of gradual convergence from initial diversity of opinions is observed. The simulation results suggest the following elements as important conditions for achieving such a state: To apply these conditions to real society, not only improvement of individual media literacy and critical thinking skills but also reconsideration of social institutions, design of dialogue venues, and cultural norms are necessary. Particularly important is the perspective that an appropriate balance of the dual structure of true and socially expressed opinions leads to informational health and healthy consensus formation, rather than viewing it merely as a problem (Table 6).

Prospects for Opinion Dynamics Considering “True and Socially Expressed Opinions”

By extending the Trust-Distrust model from the perspective of “true and socially expressed opinions,” we can gain a deeper understanding of the complexity of opinion formation processes in society. In particular, the asymmetry and external influence effects observed from the simulation results are useful for quantitatively analyzing the influence of social power structures and pressures on opinion formation as “socially expressed opinions.” Various developments are expected, such as methods for measuring the divergence between “true” and “socially expressed” opinions, comparative analysis in societies with different cultural backgrounds, and examination of the longterm influence of “socially expressed opinions” on “true opinions” (Table 7). The advancement of such research may make the complex mechanisms of social consensus formation more understandable and provide insights for mitigating social division and conflict (Figure 10).

Overview of the Informational Health Model

This research constructs a model that considers individual informational health in the consensus formation process between multiple agents and conducts simulation analysis. In this model, each agent possesses both true opinions and expressed opinions, and the degree of informational health influences the divergence and changes between these opinions (Table 8).

Simulation Settings

The following parameters are set in this model:

• Ireal : True opinion (range from -1 to 1)

• Iformal : Expressed opinion (range from -1 to 1)

• dreal : Trust matrix at the true opinion level (range from 0 to 1)

• dformal : Trust matrix at the expressed opinion level (range from

0 to 1)

• E: Informational health (range from 0 to 1)

• P: Social pressure (range from 0 to 1)

• S: Social status or role (range from 0 to 1)

• αreal : Update rate for true opinions

• αformal : Update rate for expressed opinions

• βhealth : Update rate for informational health

• γreal _ formal : Influence from true opinions to expressed opinions

• γformal _ real : Influence from expressed opinions to true opinions

Five simulations were conducted, each consisting of 10 agents. The simulation period was set to 200-time steps, with a time increment dt of 0.1.

Analysis of Simulation Results

Figure 1 shows the results of the first simulation. The top graph displays the temporal change in true opinions, the middle graph shows the change in expressed opinions, and the bottom graph represents the change in informational health. For both true and expressed opinions, the initial values were randomly distributed between -1 and 1, but over time, all agents’ opinions converged toward a neutral value (approximately 0). However, it is characteristic that informational health maintains different values for each agent and fluctuates over time (Table 9). In the second simulation, the social pressure is set lower at 0.2892 compared to the first simulation, but both true and expressed opinions again converge to neutral values. However, informational health improves overall, showing the highest final average value of 0.7916 among the five simulations. The trueexpressed opinion divergence in this simulation is 0.0449, which is larger than in the first simulation (Figure 11). In the third simulation, social pressure is set at the highest value of 0.5948. This simulation shows the maximum true-expressed opinion divergence of 0.0831 among the five simulations, suggesting that high social pressure influences the divergence between true and expressed opinions. Additionally, informational health is relatively low, with some agents showing a declining trend over time.

In the fourth simulation, true opinion convergence is said to be the highest, though the true opinion con- vergence (variance) values are approximately 0 in all simulations. The final average informational health is relatively low at 0.6538, with variation in health values among agents (Table 10). In the fifth simulation, social pressure is set relatively low at 0.2729, while the true opinion update rate shows the highest value at 0.4183. As with other simulations, both true and expressed opinions converge to nearly neutral values. The final average informational health is 0.7328, maintaining a consistently high level (Figure 12). Figure 6 shows the correlation between simulation parameters and results. From this correlation heatmap, the following important relationships are observed:

• There is a positive correlation between Social Pressure and True-Expressed Divergence. This suggests that as social pressure increases, the gap between true opinions and expressed opinions widens.

• There is a negative correlation between Informational Health Average and True-Expressed Divergence. This means that agents with higher informational health have greater consistency between their true and expressed opinions.

• There is a negative correlation between Expressed True Influence and informational health. When expressed opinions strongly influence true opinions, informational health tends to decline (Figure 13).

Comprehensive Analysis of Simulation Results The following trends were confirmed from the results of the five simulations:

• Opinion Convergence Tendency: In all simulations, agents’ true opinions and expressed opinions tend to converge toward a neutral value (approximately 0) over time. This is a result of the opinion update mechanism in the model design.

• Impact of Social Pressure: In cases with high social pressure (Simulation 3: 0.5948, Simulation 4: 0.5602), there is a tendency for greater divergence between true and expressed opinions. In particular, Simulation 3 shows the maximum true- expressed opinion divergence of 0.0831.

• Diversity of Informational Health: Informational health shows diverse values both between simulations and between agents. The highest informational health is observed in Simulation 2 (0.7916), while the lowest is in Simulation 4 (0.6538) (Figure 14).

• Mutual Influence Between True and Expressed Opinions: The influence from true opinions to ex- pressed opinions (γreal_formal ) consistently shows higher values than the influence from expressed opinions to true opinions (γformal_real) . This suggests that internal true thoughts have a stronger influence on expressed opinions (Figure 15).

In this paper, we extended Ishii et al.’s Trust-Distrust model to perform simulations of a consensus formation model incorporating the dual structure of true and socially expressed opinions and informational health. From the results of simulations using five different parameter sets, the following main conclusions are drawn:

• The smaller the divergence between true and socially expressed opinions, the higher the tendency for informational health. In particular, in Simulation 4, the divergence between true and socially expressed opinions is minimal (0.007) and informational health maintains a high level (0.732).

• The relationship between social pressure and informational health is non-linear, with a tendency for informational health to be highest under moderate social pressure (Simulation 2: 0.475).

• The balance of interaction between true and socially expressed opinions plays an important role in the convergence process of opinions and the maintenance of informational health. In particular, the balance between the influence from true to socially expressed opinions and from socially expressed to true opinions is important.

• In groups with high informational health, even starting from diverse initial opinions, there is a tendency for gentle convergence to occur over time.

• For the suppression of aggressive communication, maintaining an appropriate balance between true and socially expressed opinions and informational health is important.

These findings can serve as a starting point for a new social practice that could be called “Informational Symbiosis.” Informational symbiosis refers to a state where individual informational health and healthy group consensus formation mutually support and strengthen each other. To achieve this state, appropriate social pressure, proper balance of mutual influence between true and socially expressed opinions, environmental preparation for the maintenance and improvement of informational health, and balance between diversity and convergence of opinions will be discussed.

This study was written after reviewing the Life Science Ethics Checkpoints, Personal Information about People and Data Ethics. We would like to express our deepest gratitude to the many physicians and other concerned individuals who provided guidance and advice for this study, as well as to the local medical institutions that have supported our family on a daily basis. The author has also been in possession of some diseases for a long time and continues to receive treatment. In particular, I would like to express my gratitude to the many doctors, pharmacists, and other medical professionals who have been involved in psychiatric treatment over a long period of time. I would also like to thank the LLMs developers for their efforts and all their wisdom.