Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Alber Fares1*, Mohamad Baiz2, Sai Reddy2, Manraj Dhaliwal2 and George Fares3

Received: April 04, 2025; Published: April 14, 2025

*Corresponding author: Alber Fares, Assistant Professor of Biochemistry, Xavier University School of Medicine, Aruba

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2025.61.009594

This qualitative research examined the perspectives of students, faculty members, and administrators regarding innovative and engaging teaching methods at a medical school in the southern Caribbean, aiming to serve as a model for similar institutions in the region. Data on these perceptions were collected from school administrators, faculty members, and students to evaluate how medical education standards and quality relate to implementing innovative instructional practices. The study gathered insights into the presence and impact of groundbreaking scientific techniques. Although specific schools and levels were purposefully selected, the administrator, faculty, and student body participants were chosen randomly for the surveys and interviews. The findings highlighted a positive reception towards innovative teaching methods, with many participants expressing enthusiasm for their potential to enhance learning outcomes. Faculty members reported that incorporating interactive technologies and problem-based learning had significantly increased student engagement and understanding of complex medical concepts. Similarly, administrators pointed out that these methods fostered a more collaborative environment, encouraging students to participate actively in their education. Moreover, the research highlighted several challenges, including sufficient professional development for faculty to implement these new strategies successfully. Overall, the research underscored the importance of embracing change in medical education to prepare future healthcare professionals effectively. By sharing these insights and strategies, the study aims to inspire other regional institutions to explore and adopt similar practices, ultimately contributing to the advancement of medical education across the Caribbean.

Keywords: Caribbean; Offshore; Medical Schools; Quality; Education

Abbreviations: CAAM-HP: Caribbean Accreditation Authority for Education in Medicine and Other Health Professions; ACCM: Accreditation Commission on Colleges of Medicine; IMGs: International Medical Graduates; OCMS: Offshore Caribbean medical schools; US: United States; IMGs: International Medical Graduates; USMLE: United States Medical Licensing Exams; ECFMG: Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates; WFME: World Federation for Medical Education; SD: Strongly Disagree; D: Disagree; N: Neutral; A: Agree; SA: Strongly Agree; FDP: Faculty Development Program; PBL: Problem-Based Learning; QI: Quality Improvement; PS: Patient Safety

According to [1] there are a total of 82 medical schools located in the Caribbean, with 47 classified as offshore institutions. The World Bank (2004) defines offshore schools as primarily serving foreign students, particularly from North America, who plan to practice medicine in the U.S. and Canada. Among these 82 schools, 11 hold accreditation from the Caribbean Accreditation Authority for Education in Medicine and Other Health Professions (CAAM-HP) [2]; however, two are currently on probation. Additionally, CAAM-HP has revoked accreditation from four schools, while six others were denied accreditation, and four are awaiting review. Eight schools have received accreditation from the Accreditation Commission on Colleges of Medicine (ACCM) [3], with two schools accredited by both organizations. Notably, over 50% of graduates from Caribbean schools are engaged in primary care within the USA, and more than 75% of U.S.-born International Medical Graduates (IMGs) come from offshore Caribbean institutions [4]. According to [1] Offshore Caribbean medical schools (OCMS) began their establishment in the late 1970s, by 2013, over three-quarters of the United States (US) International Medical Graduates (IMGs) had graduated from these institutions [5]. Many OCMS also welcome students from Asia, particularly South Asia, with numerous graduates returning to their home countries to practice medicine [6]. Students from the Middle East and West Africa, especially Nigeria and Ghana, are also part of the student body [6].

Caribbean schools offer a range of educational programs [7]. Student performance on the United States Medical Licensing Exams (USMLE) and the certification rates from the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) vary between schools and across different Caribbean countries. Some countries in the Caribbean have established regulations or national accrediting bodies, whereas others do not mandate accreditation [8]. The quality of medical schools can vary greatly, as highlighted in [9]. While some well-established and well-funded institutions meet international standards, others face challenges such as poorly qualified faculty, limited research opportunities, inadequate student support, and fragmented curricula [4]. Beginning in 2023, to qualify for the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) certification, physicians must graduate from a properly accredited medical school that aligns with criteria comparable to global standards, such as those established by the World Federation for Medical Education (WFME) [9]. Students from North America generally enroll in older, well-established schools that often provide educational programs meeting North American standards, thereby enhancing their chances of securing residency placements [6]. In contrast, students from the developing ‘South’ primarily attend newer and emerging institutions [6]. These newer offshore Caribbean medical schools (OCMS) tend to be smaller, typically housing between 10 to 20 faculty members in basic sciences. A recent study highlighted the challenges facing undergraduate education in OCMS [10]. Competition among online colleges and medical schools (OCMS) in attracting students is intense [6]. According to [9] Many newcomers are disrupting the market by offering significantly lower tuition fees. Reported tuition rates vary dramatically, ranging from under USD 50,000 to USD 250,000 [6], with some new institutions providing the entire program for approximately USD 40,000. The most cost-effective teaching model primarily relies on traditional lectures conducted in large classrooms, effectively delivering information to many students. Numerous OCMS utilize ‘agents’ to recruit students. While published data is limited, insights gained from experience and discussions with fellow educators suggest that most agents earn a commission of approximately USD 3,000 for each student they help admit.

Additionally, some agents may receive incentive payments as students advance to higher semesters [6]. In recruiting Asian and African students, OCMS faces competition from medical schools in China and Eastern Europe, which can offer lower tuition, larger teaching hospitals, and more aggressive marketing strategies. The student intake at most new OCMS is typically low, often fewer than 40 students, resulting in resource constraints. A lack of capital is frequently available for implementing innovative small group learning methods and modern educational technologies [6]. According to [9], many students plan to return to their home countries outside of North America to practice after graduation. This trend could pose challenges for OCMS. The CAAM-HP standards are primarily based on those established by the General Medical Council in the United Kingdom and the US Liaison Committee on Medical Education. First-time pass rates, particularly for the USMLE Step 1, are used to evaluate the quality of the basic sciences program and are heavily promoted by medical schools in their marketing materials [6]. However, taking the USMLE is costly and demands extensive preparation, which may deter students who do not intend to practice in North America from pursuing it [6]. [11] Quality medical education is a guiding light, illuminating the right path for humanity to advance. Its aim goes beyond mere literacy; it fosters rational thinking, knowledge, and self-sufficiency. Critical thinking is essential for ensuring safe, competent, and skilled practice. Innovation creatively combines knowledge, skills, and attitudes to generate new, original, and rational ideas [12]. There is a continual need for innovation in medical education to adapt to and work in evolving settings [12].

The healthcare field has long valued innovation in practice and education. Over time, healthcare professionals have faced challenges such as shortages of students and educators, technological advancements, changes in healthcare delivery models, a more diverse patient population, and a shift toward patient-centered care [12]. Most educators strive to convey knowledge as they perceive it; therefore, any communication method that achieves this goal without undermining its purpose can be deemed an innovative teaching method [12]. [11] Numerous medical schools have initiated curricular modifications emphasizing core primary care clinical clerkships. Incorporate learning objectives and competencies deemed essential for future healthcare delivery, including faculty development and internal evaluation elements [13]. Many schools that have adopted these curricular changes now require students to engage directly with managed care organizations and participate in specific demonstration projects to equip them with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for effective care management [13]. Health education is critical in improving patients’ quality of life and is essential in healthcare. The significance of medical education is that discussing treatment options and promoting holistic health skills can foster patient engagement [14]. Efforts in medical education to translate science into practical clinical applications necessitate a framework of interdisciplinary collaboration [15]. This framework should integrate working platforms that promote exchanging knowledge, expertise, and tools [15]. Central to this translational process is the concept of creativity, which is described as a combination of skills essential for generating original and valuable ideas [8]. While creativity is widely regarded as a critical skill to develop, it remains challenging to define and, even more so, to measure [16].

Researchers investigated which instructional methods enhance student learning outcomes [17]. Strong evidence suggests that active- learning or student-centered strategies yield superior learning results compared to passive- learning or instructor-centered methods, whether in-person or online [18-20]. Active learning techniques involve student engagement through activities or discussions during class, while passive learning methods focus on lengthy explanations from the instructor [18]. The researcher’s proposal was submitted to a medical school in the southern Caribbean, where it received approval from the school’s research committee and the Institutional Review Board (IRB). The IRB mandates that the researcher assesses any potential risks to participants, which may encompass physical, psychological, social, economic, or legal harm. Following the IRB’s approval, the school granted permission to conduct surveys and interviews with students, faculty, and administrators [21]. In qualitative research, the researcher is a key instrument for data collection [22]. In this study, the researcher functioned as the data collection manager and refrained from actively participating. As is common in qualitative research, it can be challenging to distinguish findings without the influence of the researcher’s background [23].

In this study, trustworthiness was established through consistent data collection methods. Surveys were conducted using an online Google Form, which was emailed to participants after they signed the research consent form [24]. Before data collection, survey items for students, faculty members, and administrators were field-tested. The researcher utilized member checking to ensure the accuracy of the survey and interview transcripts. The survey and interview findings were compared and triangulated to highlight differences in perceptions among students, faculty members, and administrators [24].

Additionally, an external auditor was engaged to confirm that the data analysis was reliable and free from any personal bias from the researcher. Participants in the interviews had the option to choose how their responses were recorded: in person, through Google Form, by phone, or via video conference, under the US safety regulations [24]. Surveys and interviews were the primary tools for collecting data in this study. To enhance the reliability of the research instruments, the survey and interview questions were piloted with a small group of educators prior to the study, ensuring that they effectively addressed the research objectives [24]. This study took place in the Fall 2024 semester. The researcher participated significantly in the study, which involved 35 students, 20 faculty members, and 8 school administrators. Notably, all faculty members and administrators from this school participated fully in the research survey. This high level of engagement ensured that the findings were comprehensive and reflective of the diverse perspectives within the institution. The data collected provided valuable insights into the academic environment, highlighting areas of strength and potential improvement. By including a broad range of participants, the study captured quantitative metrics and qualitative experiences, enriching the overall analysis. As a result, the research is positioned to inform future policy changes and drive institutional development, ultimately enhancing the educational experience for everyone involved. Unfortunately, we did not receive significant number of interviews due to the busy day for both students and school staff.

Presentation of Findings

Research explored which teaching methods improve student learning outcomes [17]. The school serves approximately 120 students across various programs, including premedical, medical, pre-veterinary, veterinary, and nursing, along with 20 faculty members and 8 administrators. Each survey conducted for students, faculty members, and school administrators included 20 multiple-choice questions, and this research highlights specific questions from those surveys.

Students Survey

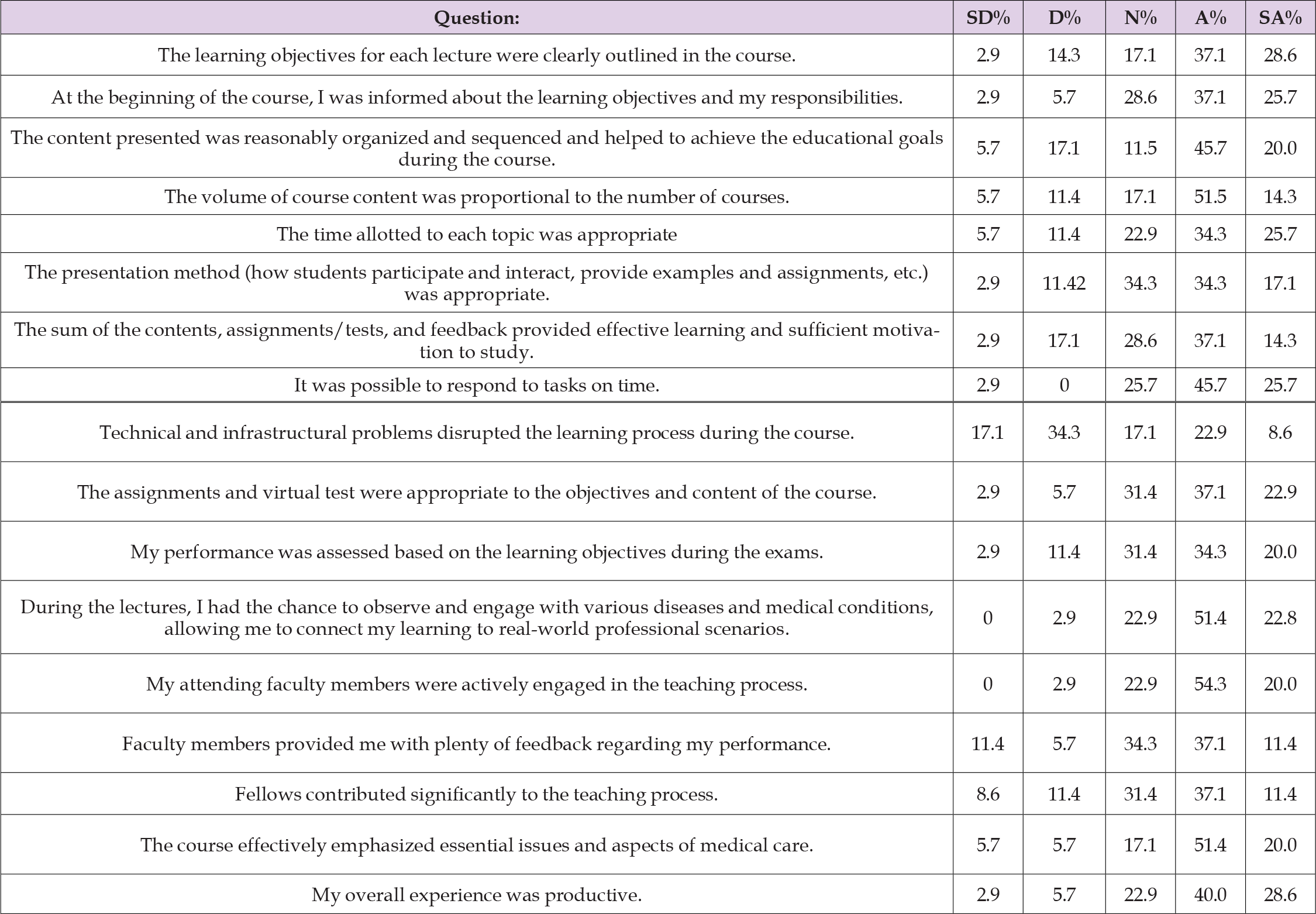

Student ratings of instruction, often referred to as “course evaluations,” are the primary method for students to give feedback on faculty teaching, course design, and delivery. This feedback is relevant across all disciplines, programs, degrees, and types of institutions [25]. One key reason for conducting student ratings of instruction is to facilitate ongoing quality improvement in courses and teaching methods. Collecting student feedback on teaching and course delivery is vital, as students experience the instruction firsthand and can provide valuable insights into the learning and assessment processes and suggestions for enhancing teaching effectiveness [26]. [27] Additionally, institutions implement student evaluations to comply with particular or implied regional and/or professional accreditation standards. [28-32] This research gathered responses from 35 student surveys. A survey was carried out after each student signed the research consent form; the surveys were then emailed out individually using Google Forms. These students value convenience, flexibility, and the opportunity to work while pursuing their studies, and they tend to be older than the typical college-age demographic [33, 34]. The survey aimed to gather insights into the students’ experiences and perspectives on the research topic. Each student was given ample time to complete the study, ensuring that their responses could be thoughtful and comprehensive. The data collected would be instrumental in shaping the research direction, highlighting trends, preferences, and areas needing further exploration. As the responses began to trickle in, it became clear that the students offered valuable feedback, which promised to enrich the study’s outcomes and provide a deeper understanding of the subject matter. Figure 1 shows that the students participating in the survey come from diverse nationalities: 45.7% are American, 22.9% are Canadian, 20% are Aruban Dutch, and 11.4% hail from India, Suriname, and Brazil. Figure 2 shows that the students participating in this survey were 51.4% males and 48.6% females. Figure 3 shows that the students involved in this survey represent a range of ages: 77.1% are under 25 years old, 11.4% are between 25-30, 5.7% fall into the 30-39 age group, and another 5.7% chose not to disclose their ages. Figure 4 shows that the students participating in this survey are registered in a range of programs: 40% are studying medicine, 22.9% are in veterinary studies, 20% are pursuing premedical courses, while 8.6% are enrolled in pre-veterinary programs, and another 8.6% are in nursing programs. A range of multiple-choice questions was presented to the students in the survey, offering response options of Strongly Disagree (SD), Disagree (D), Neutral (N), Agree (A), and Strongly Agree (SA). The students’ responses were categorized in the following manner in Table 1.

Table 1: A range of multiple-choice questions was presented to the students in the survey, offering response options of Strongly Disagree (SD), Disagree (D), Neutral (N), Agree (A), and Strongly Agree (SA).

Faculties Survey

Figure 5 [35] Concluded the six essential aims of quality in healthcare: safety, timeliness, efficiency, effectiveness, equity, and patient- centeredness. These core concepts should be integrated by all physicians throughout their learning journey, from the start of undergraduate education to the culmination of their medical careers. For this integration to happen, Quality Improvement (QI) and Patient Safety (PS) must be recognized as vital elements of the scientific basis of medicine. Learners must encounter the terminology of quality improvement early in their training, enabling them to adopt the behaviors, values, and norms that foster a culture of quality and safety. Faculty development should encompass three key elements: a shared academic and clinical vision, the capacity of medical school teaching hospitals, and the development and assessment of learning across the continuum [35]. Faculty surveys are essential for gathering insights and feedback from educators, helping institutions improve their programs, policies, and overall environment. These surveys allow faculty members to voice their opinions on various aspects of their work life, such as curriculum design, administrative support, resources, workload, and professional development opportunities. By analyzing the data collected, universities and colleges can make informed decisions to enhance faculty satisfaction, foster a positive and productive work atmosphere, and ultimately contribute to the institution’s success. Engaging faculty in this process empowers them and strengthens the collaborative efforts between administration and staff, ensuring that educational goals are met with efficiency and innovation. Figure 6 shows that the faculty members participating in this survey were 75% males and 25% females. Figure 7 shows the faculty members participating in this survey encompass a variety of age groups: 35% are aged between 50 and 60 years, 20% fall within the 40 to 49 age range, 15% are between 30 and 39, 10% prefer not to respond, and another 20% are 60 years old or older. Figure 8 shows that the faculty members participating in this survey hold the following degrees: 65% possess doctoral degrees, 30% have master’s degrees, and 10% hold bachelor’s degrees. Figure 9 shows that the faculty members participating in this survey possess a diverse range of teaching experience: 65% have 20 or more years of experience, 35% have between 16 to 20 years, 15% fall within the 11 to 15-year range, 25% have 6 to 10 years, and 5% have 1 to 5 years of teaching experience. Figure 10 illustrates the insights gathered from faculty members who participated in this survey regarding professional development (PD): 40% believed that PD sessions significantly improved their teaching, 30% indicated they had not attended any PD sessions in the last five years, 25% maintained a neutral perspective on PD and 5% felt that it was entirely unhelpful. The survey presented a range of multiple-choice questions to the faculty, offering response options. The faculty responses were categorized in the following manner: Figure 11 poses the question: Which strategies do you consider most effective for your students? Problem-based learning was the most selected option, followed by active learning strategies and traditional science instruction. Figure 12 asks How you keep your curriculum relevant and in tune with industry trends and advancements. The responses indicate that the faculties have offered substantial evidence to maintain the curriculum’s alignment with current industry developments. Key components include industry collaboration, continuous professional development, curriculum review committees, integration of emerging technologies, feedback mechanisms, and research and development. Figure 13 asks, “Can you provide examples of how you integrate experiential learning opportunities into your courses?” The responses include internship integration, research projects, service-learning, capstone projects, simulations, and role-playing.

Administrators’ Survey

According to [36], education is an essential element of society, with the quality of educational leadership significantly influencing students’ learning experiences. Educational leaders, including administrators and instructional leaders, have the critical task of guiding and motivating faculties and students towards academic excellence and personal development. Effective educational leadership significantly affects the learning environment and student outcomes. By offering strategic guidance, promoting a positive school culture, and applying best instructional practices, educational leaders cultivate an atmosphere that fosters learning, encourages student success, and improves overall educational quality [36]. As educational environments keep changing, gathering insights from dedicated school leaders is crucial. This survey seeks to capture administrators’ perspectives, experiences, and aspirations as they address the challenges and opportunities present in today’s educational landscape. Their responses will enhance our understanding of how school leaders influence education’s future. Figure 14 illustrates the various roles of the school administrators who participated in this survey. Figure 15 asks: Can you describe the level of support offered to students regarding academic advice and mentorship? There are mixed responses, including personalized academic advising, peer mentorship programs, faculty mentorship, workshops and seminars, online resources, and career and internship advising. Figure 16 raises an important question: How does the institution gather feedback from students, faculty, and healthcare professionals to enhance their educational experience? Responses vary, including regular surveys and feedback forms to identify recurring themes, focus groups, and discussions to find in-depth solutions. These advisory committees review feedback and supervise changes, workshops on continuous professional development, and transparent communication to build trust and value input. Figure 17 poses a significant question: How does the institution foster diversity and inclusion within its medical education program? The responses differ and include actively recruiting diverse students and faculty, offering scholarships for underrepresented groups, implementing a curriculum that emphasizes cultural competencies, conducting workshops on implicit bias and equity, establishing mentorship programs with diverse role models, providing support for diversity and inclusion groups, and forming partnerships with community organizations. Figure 18 raises an important question: How does the school assess the success of its graduates in their careers? The answers vary and include monitoring employment rates and job placements in preferred fields, tracking board certification rates to indicate competence and preparedness, gathering employer feedback regarding graduates’ performance and professionalism, and conducting alumni surveys to gain insights into career satisfaction and accomplishments.

Students Survey

The student surveys reveal that learners come from various cultures, countries, genders, and ages, showcasing how this rich diversity creates an engaging and dynamic learning environment. This setting encourages students to explore different perspectives, share their traditions, and learn from each other. Such an inclusive atmosphere enhances educational experience and equips students to succeed in a globalized world, fostering respect, empathy, and collaboration among the future healthcare professionals of tomorrow. As the world becomes more interconnected, ‘diversity’ and ‘super diversity’ increasingly become the standard within school populations [37]. When collecting student feedback, the institute employs various strategies to support them, including regular surveys and feedback forms to identify key themes. They communicate this data to their students through feedback to guide and support their continuous development [38]. The diverse range of programs provided by the school distributions showcases the student body’s various interests and career goals. Each program presents distinct opportunities and challenges to meet its students’ unique needs and aspirations. With a notable emphasis on the medical and veterinary sectors, the survey indicates a strong interest in healthcare professions. This trend may reflect the rising demand for skilled professionals in these areas, fueled by advancements in medical science and a heightened focus on animal welfare.

As these students progress in their academic pursuits, they are well-positioned to make significant contributions to their fields, helping to shape the future of healthcare and veterinary services. The student surveys indicate that a significant percentage of students agree with all statements in Table 1 that concern the course’s clearly defined learning objectives and responsibilities. Learning objectives (LOs) communicate the purpose of instruction to students, other instructors, and the academic field [39,40]. The content was structured effectively and aligned with educational objectives, providing ample time for each subject. The presentation methods encouraged student interaction, while the assignments successfully inspired learning. In contrast to traditional lectures, practical teaching and learning strategies enhance student engagement, knowledge retention, self-directed learning, communication skills, teamwork capabilities, and peer discussions. [41-45]. Although there were some technical difficulties, the tasks remained manageable and aligned with the course objectives. Assessments accurately reflected the learning goals, and engagement with various medical conditions strengthened real-world connections. It is stated that an essential factor in the general achievement of learners studying in higher education is learners’ engagement [46,47]. Faculty members engaged in students’ lives, providing valuable insights, while fellows made essential contributions. Overall, the experience was fruitful and highlighted critical issues in medical care. Higher education institutions are being called upon to lead transformative changes in health care education. This begins with assessing the curricula and educational outcomes across different health disciplines, especially in areas where Interprofessional Collaboration (IPC) can seamlessly integrate [48].

Faculties Survey

The survey aimed to gather insights into the diverse perspectives and experiences of the faculty, reflecting a cross- section of the academic community. In addition to age and gender, the survey explored various aspects such as teaching methodologies, research interests, and professional development needs. This diversity in representation ensures a comprehensive understanding of the faculty’s contributions and challenges. Promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion among students and faculty is a key priority for educational institutions, as it plays a vital role in cultivating inclusive and fair societies [49]. Diversity refers to the range and demographic composition of groups and organizations, while inclusion emphasizes the importance of integrating and empowering diversity within organizational systems and processes [50]. Equity highlights the need to allocate organizational resources based on the specific requirements of the workforce [51]. The faculty members’ impressive array of qualifications and experience highlights a strong foundation of knowledge and expertise within the institution. Such diversity not only enriches the learning environment but also ensures that students receive guidance from individuals who are well-versed in both the theoretical and practical aspects of their fields [52,53].

Faculty involved in these surveys bring a wealth of experience, equipping educators to adapt to diverse educational needs and foster an engaging, supportive environment for academic growth. Additionally, the combination of fresh insights from newcomers to the profession and the seasoned perspectives of veteran educators creates a dynamic and innovative approach to teaching and curriculum development. This balanced team composition is a foundation for building an educational environment that honors tradition and progressive strategies, ultimately benefiting students and the larger academic community. In recent years, various studies and policy decisions in the USA have been shaped by the notion that a teacher’s experience has little impact on their effectiveness after the initial two to three years of their career [54-57]. For example, a policy brief published in 2010 emphasized the benefits of teaching experience in US schools, stating that “teachers show the greatest productivity gains during their first few years on the job, after which their performance tends to level off” [56]. Participants also provided feedback on institutional support and opportunities for collaboration. These insights are invaluable for shaping future policies and initiatives that foster an inclusive and supportive environment for all faculty members. By addressing its faculty’s unique needs and aspirations, the institution can enhance its academic excellence and community engagement.

To thrive and maintain performance in the competitive educational landscape, universities must focus on developing the necessary competencies of their faculty and implementing essential institutional support strategies. These strategies should enhance the effectiveness of modern knowledge- sharing practices, boost quality research productivity, and streamline administrative processes, among other factors, for their employees. Consequently, the effectiveness of faculty job performance is crucial in achieving the university’s central mission [58]. The participation feedback gathered from faculty members who participated in this survey on professional development (PD) indicates the following: 40% believed that PD sessions significantly improved their teaching, 30% stated they had not attended any PD sessions in the last five years, 25% expressed a neutral stance on PD, and 5% viewed it as entirely unhelpful. This suggests that faculty may lack adequate opportunities for professional development or that the school does not offer sufficient PD sessions, relying instead on their personal experiences. A faculty development program (FDP) is regarded as a coherent sum of activities targeted at strengthening and extending teachers’ knowledge, skills, and conceptions in a way that will change their thinking and actual educational behavior [59]. FDP is also considered an effective instrument for facilitating university change4 and improving students’ performance. Therefore, FDP can be summarized as a structured activity encompassing an extensive range of events steered by the faculty and the organization [60]. The most favored learning strategy among the participating faculty was problem-based learning, while team-based learning was the least preferred option. Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is an educational strategy that transitions the teacher’s role to focus on the student, promoting self-directed learning.

While PBL has been implemented in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education, its effectiveness remains debatable. The author aimed to evaluate the existing international evidence regarding the efficacy and applicability of the PBL methodology in undergraduate medical teaching programs [61]. Regarding the school curriculum’s connection to the medical industry, faculty responses indicate that they have gathered substantial evidence to align the curriculum with contemporary industry developments. The most essential component was research projects, followed by simulation and role-playing as the second element. Conversely, project-based learning was the least selected component. In medical education, the curriculum serves as the foundation for cultivating skilled, ethical, and adaptable healthcare professionals capable of addressing the needs of both patients and society. It outlines the structure, content, and methods for training and evaluating future physicians and how students engage in their learning journey [62]. The significance of the curriculum is multifaceted: it informs stakeholders, including students, educators, patients, and the broader public about what to expect from the educational program; it also establishes benchmarks for program evaluation and accreditation [62]. Educators play a vital role in the design and implementation of the curriculum. It can be argued that this responsibility is among the most crucial and demanding aspects of a teacher’s role [62]. When it came to learning opportunities, the preferred choices were research projects, simulations, and role- playing activities. One of the key steps in developing a curriculum is incorporating simulation-based medical education. Simulation is a broad term that denotes an artificial representation of real-world processes aimed at achieving educational objectives through experiential learning [63].

Administrators’ Survey

The school administrator offers various forms of academic support for students, including personalized academic advising, peer mentorship programs, faculty mentorship, workshops and seminars, online resources, and career and internship devising. [64] It high lighted the importance of assessing the quality of school life along with students’ interests, expectations, reactions to their teachers, and commitments. The behaviors and traits that society anticipates from individuals, particularly primary school students, can only be cultivated through effective management and a healthy organizational structure. To ensure that students possess the academic, social, physical, mental, and developmental qualities essential for their growth and success, the primary responsibility for planning and conducting research in this area lies with the school administrator [64].

Furthermore, the administrators in this survey promote diversity within the medical education program through various strategies. These include actively recruiting a diverse student body and faculty and a curriculum emphasizing cultural competencies. The growing cultural diversity in classrooms mirrors more significant societal shifts influenced by migration, globalization, and changing demographic trends. As students from diverse cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic backgrounds join the education system, educators encounter the vital challenge of addressing their varied needs. Cultural competence, the ability to engage effectively with individuals from different cultures, has emerged as a crucial skill for teachers [65]. Finally, the school evaluates the success of its graduates in their professional journeys through a range of strategies. The administrator in this survey noted that one of the main methods used is conducting alumni surveys to gather insights into their career satisfaction and achievements.

The findings indicated a favorable response to innovative teaching methods at the Caribbean medical school involved in this study, with many participants expressing enthusiasm about their potential to enhance learning outcomes. Faculty members observed that using interactive technologies and problem-based learning significantly increased student engagement and understanding of complex medical concepts. Similarly, administrators pointed out that these methods fostered a more collaborative environment, encouraging students to engage in their education actively. However, the study highlighted specific challenges, such as adequate training and resources to implement these new strategies effectively. Most faculty members stressed that ongoing professional development and institutional backing were crucial for successfully adopting innovative practices, although some felt that professional development was not beneficial. The research underscored the importance of embracing change in medical education to prepare future healthcare professionals. By sharing these findings and strategies, the study aims to motivate other regional institutions to explore and implement similar practices, ultimately advancing the evolution of medical education across the Caribbean.