Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Biruk Kelbessa1, Teka Girma2 and Tadele Shiberu2*

Received: February 11, 2025; Published: February 21, 2025

*Corresponding author: Tadele Shiberu, Ambo University, Ethiopia

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2025.60.009483

Appropriate health care-seeking behaviour of mothers/caregivers for common childhood illnesses could prevent a significant number of child deaths due to childhood illnesses, currently, there are no studies in Ambo town, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Assessment of Health Care Seeking Behaviour for Common Childhood Illnesses and Associated Factors among Mothers’ Having Under 5 Children in Ambo Town. A total of 476 mothers with under-five children who experienced diseases within eight weeks before the survey were selected for this study. A community-based cross-sectional study design was employed from June to August 2020. All children who are under 5 years old in the town were included in the study. A sampling technique was used to interview the mother. Data were entered in Epi-data version 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 16.1. The completeness and consistency of the data were checked and cleaned. Logistic regression was applied to see the association between dependent and independent variables. A total of 476 mothers were enrolled in the study giving an overall response rate of 100%. A total surveyed mothers who had 234 sick children observed these children had a cough at any time in the last 8 weeks 119 (58.9%) when had an illness with a cough, did he/she breathe faster than usual with short, rapid breaths or had difficulty breathing 63 (33.7%) for less than two weeks 167 (89.3%). Awareness of common childhood illnesses, perceived illness severity, perception of early treatment, and child age between 12-24 months were positively associated with mothers’ or caregivers’ healthcare-seeking behaviour. Efforts should be made by government and non-governmental organizations to improve the mothers’ healthcare-seeking behaviour by providing information.

Keywords: Mothers; Health Care Seeking Behaviour; Childhood; Illness; Under Five Years Children; Ambo Town

Common childhood diseases are diseases that are responsible for considerable child mortality, morbidity, and disability in the world. Acute Respiratory Infections, diarrheal disease, malaria, and measles constitute diseases that exert a major impact on the health of under-five children [1]. Children are the most vulnerable age group in any community; hence, the under-five mortality rate (U5MR) is a widely used demographic measure and an important indicator of the level of welfare in countries [2]. In this regard, considerable progress has been made in decreasing the U5MR, which has declined nearly by 50% globally between 1990 and 2015 and by 60% in Ethiopia between 2000 and 2016 [3]. Globally, the total number of under-five deaths declined from 12.7 million in 1990 to 5.9 million in 2015 [4] Despite these achievements and the fact that most child deaths are preventable or treatable, many countries still have unacceptably high levels of under-five mortality [4]. Of the global under-five deaths, most deaths (98.7%) arise in developing countries (United Nations Children’s Fund, World Health Organization, World Bank, United Nations Population Division, 2015), and approximately half (49.6%) occur in sub-Saharan Africa alone in 2015 [5]. More than half of early childhood complications and deaths are due to ill health that can be prevented or treated with simple and affordable interventions. In sub-Saharan Africa, 1 in 12 children dies before celebrating their fifth birthday [6,7] and 1 in 11 Ethiopian children dies before their fifth birthday [8]. Infectious diseases turn out to be the most common causes of child morbidity and mortality in most developing countries; Ethiopia is at the forefront [8,9]. The top five leading causes of morbidity in Ethiopia for children under five years are infectious diseases; diarrhea (20%), pneumonia (19%), acute respiratory infections (ARI) (15%), and acute febrile illnesses (AFI) (7%) [10]. Furthermore, they are major causes of under-five mortality as well as inpatient admissions [11]. However, significant numbers of children continue to die without appropriate treatment and ever reaching health facilities or due to delays in seeking care in developing countries [12].

The highest rates of child mortality continue to be in Sub-Saharan Africa where, in 2009, one in every eight children (129 per 1000 live births) died before their fifth birthday a level nearly double the average in the developing region as a whole (66 per 1000) and around 20 times the average for developed regions (6 per 1000) [13,14]. Delays in seeking appropriate medical care is one of the major factors contributing to severe disease among children presenting to hospitals with severe forms of malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea [15]. In Ethiopia, 50% of children under-five mortality globally, with 194,000 deaths every year [13]. More than one third of the deaths are largely due to communicable diseases that could be easily prevented and treated using affordable and low-technology interventions [16], even though there are great achievements in decreasing infant and child mortality from year 2000 to 2011, still large proportions of Ethiopian children are suffering from diarrheal diseases, respiratory problems and malnutrition [17]. In response to the country’s health problem the government introduces Health Extension Program (HEP). HEP was designed based on the concepts and principles of Primary Health Care, to improve the health status of families, with their full participation, using local technologies and the community’s skills and wisdom [18].

Mothers in Ethiopia, however, often do not have sufficient knowledge of signs that their child’s health is in danger, or of appropriate treatments, or access to appropriate health services. Poor mothers are also more likely to live in remote areas, which can lead to delays in seeking care, and to fatalities. A mother’s care-seeking behavior is therefore particularly important in resource-poor countries like Ethiopia [19]. Health care seeking behavior is poor and only a small proportion of children receive appropriate treatment [20]. The top five leading causes of morbidity in Ethiopia for children under five years are infectious diseases: diarrhea (20%), pneumonia (19%), acute respiratory infections (ARI) (15%), and acute febrile illnesses (AFI) (7%) [21]. Furthermore, they are major causes of under-five mortality as well as inpatient admissions [22]. Despite some studies in some parts of Ethiopia about health care-seeking behavior for common childhood illnesses, still there is an information gap in Ambo town for it is not investigated. Hence, assessing health care seeking behaviour for common childhood illnesses and associated factors is useful to design appropriate interventions for the improvement of child health in the study area.

Description of the Study Area

The study was conducted at Ambo Town which is found in the Ambo district, western Shoa zone of Oromia regional state which is located at 110 km from Addis Ababa to western Ethiopia. The geographical coordinates of 858’59.988”N latitude and 3751’0.000”E longitude with an altitude of 2076 meters above sea level.

Study Design, Source of Population, and Sample Size Determination

A community-based cross sectional study design had employed. All childhood who have infant age of 28 days to 5 years in the town were included in the study. Study subjects were mothers who had under-five year children experienced disease within the two months before the survey and were selected for interview from selected kebeles. The study population was under-five year children who experienced disease within the two months before the survey. All [N=3000] the sources of the population was taken children five and under-five years living in Ambo Town during the study period.

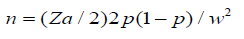

The sample size was determined using the single population proportion formula.

Where:

P=proportion of childhood who sought medical care

W=margin error of 5%,

Zα/2=critical value for normal distribution at 95% confidence

level.

If the total population is less than 10,000 we use the correction

formula

Where:

Nf = minimum final sample size

n = a minimum sample size

N=a total number of children under five years

(where n: the required sample size, p=0.563 since there was previous research conducted in the study area.)

n = (1.96)2 (0.563)*(1-0.563) /(0.05)2

n = (1.96)2 (0.563)*(1-0.563) /0.000625 = (3.8416*0.25*0.25 / 0.000625 = 216.3

Therefore, the population size was 216 children under five years.

Then design effect 2 is used because multistage sampling to minimize sampling error

= (216.3 x 2) = 433

By assuming non-response rate 10%, the total sample size will be:

Sample size = (433 x10%) + 433=476

Therefore, the population size was 476 children and under five years.

Sampling Procedure

Ambo town have sex kebeles, all of the kebeles were selected purposively by considering estimated number of the households and from the total town kebeles. The eligible mothers were selected from all kebeles by searching every other household. When the selected house hold not eligible, the subsequent households were asked until eligible mothers found. In the cases of more than one index mother of under-five children per household, one mother was selected by lottery method. When there was more than one sick child per mother, mothers were asked about the morbidity experiences of the recently sick child within the eight weeks before the survey to examine their health care seeking behaviour for common childhood illnesses (Figure 1).

Data Collection Tool and Methods

Structured interviewer administered questionnaire were designed by researcher after reviewing literatures which were previously been done on this topic [4]. The questionnaire was prepared in English language and then translated to Afan Oromo (local language) and re-translated back to English to check for any inconsistencies. Training was given for data collectors before the pre-test and the beginning of the actual interviews. Since the pre-test investigator targeted multiple sites for participant selection and data collection, a three-member team of extension works were recruited from the Ambo town health centre, trained and dispatched to collect data from the study sites. This team of research assistants was assisted in the data collection process by trained local volunteers resident in the communities in which the data collection took place. Working with the support of trained local volunteers, the team of extension workers used a door-to-door approach to recruit participants for the study from the pre-identified sites. A maximum of one participant was recruited from each household to reduce unnecessary duplication of responses. The investigator checked data completeness. Double entry of data was carried out to prevent data entry errors.

Data Quality Control

The data collectors were fluent in the local language/Afan Oromo and knew the culture of that community. Intensive training was given to the data collectors on how to complete the questionnaire. To avoid ambiguity and ensure the reliability of data, the questionnaires were pre-tested among mothers with similar socio-demographic backgrounds who were not part of the study. After pre-testing, the necessary modifications/standardization was made in the questionnaire. The completeness of the questionnaire was checked and the pre-coded data was entered into a computer, cleaned, and validated using SPSS version 18.1 software.

Data Analysis

Data were entered in Epi-data version 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 20.0. The completeness and consistency of the data were checked and cleaned. A descriptive analysis was made and measures of central tendency were also determined. Independent variables with p-value<0.05 in multiple logistic regression models were considered significant predictors of health-seeking behaviour of common childhood illnesses. The results were presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

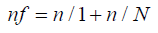

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study: A total of 476 mothers were involved in this study giving an overall response of the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents in the study area. All the respondents were selected from the target area of Ambo town, West Shewa, Oromia Regional State of Ethiopia. Majority 294 (61.8%) were aged between 25-50 years, followed by 179 (37.6) who were aged between18-24 years while the rest 3 (0.6%) who were young respondents age above 51 years of age. The ages of respondents were relevant to the study since views from people of diverse age categories were obtained. A total of 476 respondents 468 (98.3.9%) of the mothers were currently married/cohabiting with their husbands and 8 (1.6%) of the mothers were currently not married (never married, divorced and widowed) during the study period. Most of the respondents, 348 (73.1%) were Protestant in religion followed by Orthodox 115(24.2%), Muslim 10 (2.1) and Wakefata 3 (0.6%). On the other hand, almost all respondents, 452 (95.0%) were from Oromo ethnic group and followed by Amahara 22 (4.6%). Regarding the occupation of respondents, the study findings showed that majority of the respondents 277 (58.2%) were housewife while 140 (29.4%) were farmers respondents while government employee 22 (4.6), housemaid 18 (3.8, respectively. The rest 17 (3.6%) were none of the above occupations. The marital status of respondents was relevant as it helped in examining the relationship between respondents’ status and home mother management. Regarding their educational status, the majority of the mothers were in grade 9-12 education 155 (32.6%), followed by above grade 12 education 153 (32.1%) and elementary education 143 (30.1) while 29 (5.2%) were illiterate. Of the total study subjects interviewed, 352 (73.9%) reported the overall family size of their households was less than five persons while only 124 (26.1%) of them. Regarding the average monthly income of the household, 136 (28.6%) of the respondents had monthly income between 2001-3000 Eth. Birr, followed by 119 (25%) between 1001-2000, 98 (3001-5000), 55 (11.6%) less than 1000 and 68 (14.3%) Eth. Birr monthly income, respectively. The family size in households showed 352 (73.9%) and 124(26.1%), < 5 and ≥ 5 members per household, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of mothers/caretakers (n=476) in Ambo Town, West Shewa Zone, Oromia Regional State, August 2020.

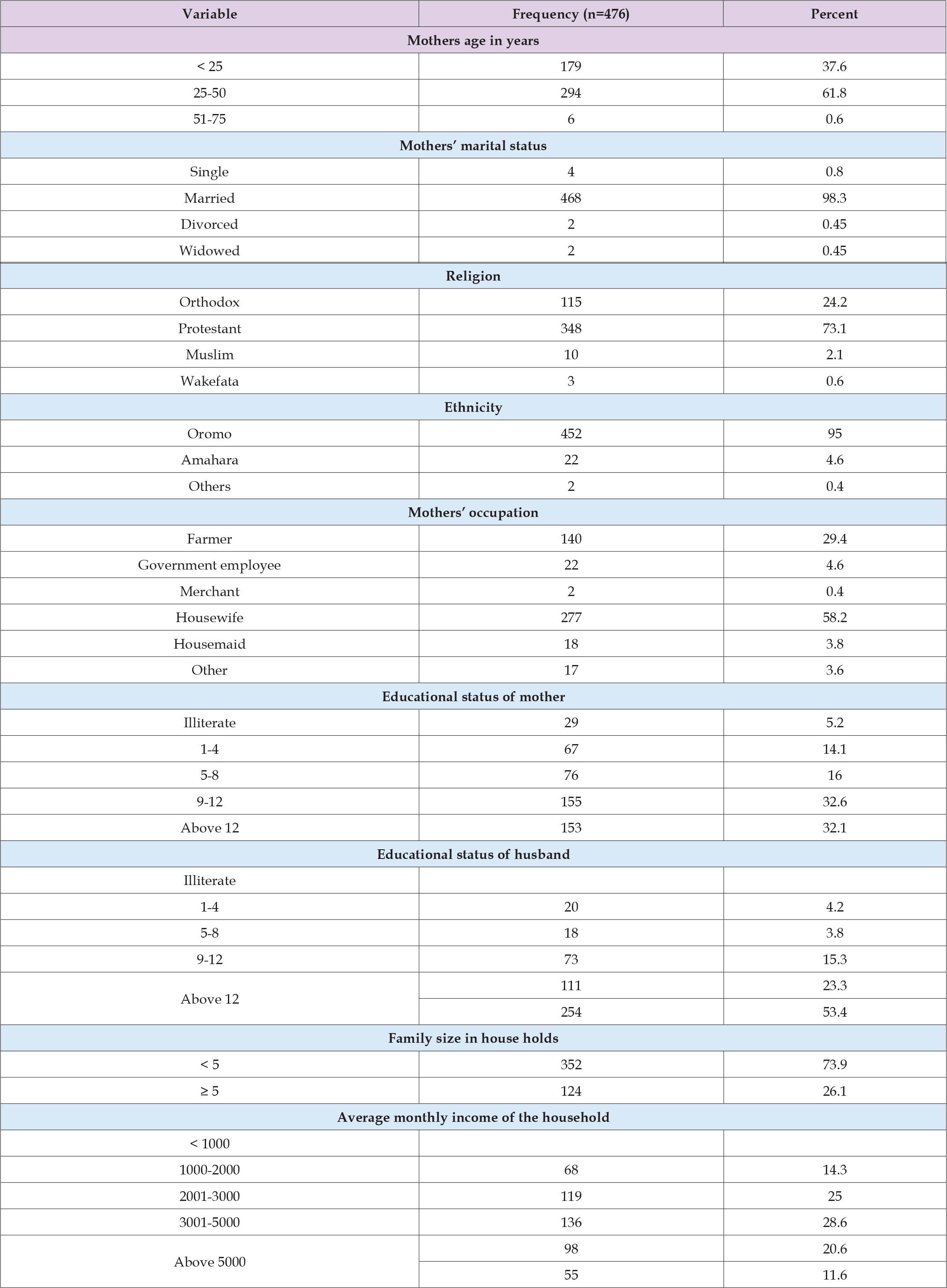

Child Health-Related Information: The result of the survey indicated in Table 2, of 476 respondents 234 sick children were reported, below six months 10 (2.1%), 6-11 months 27 (5.67%), maximum number of sick children were recorded in one year 88 (18.49%), followed by two year 56 (11.76%) and then decline to 29 (6.09%) in three years, 21 (4.41%) in 4 years and 5 years 3 (0.63%) in of those females were dominant in gender 122 (52.14%). The study findings in Table 1 showed the number of symptoms he/she has had at any time in the last 8 weeks majority of symptoms were 143 (61.11%) two and above times while 91 (38.89) once within the last 8 weeks. The children have had surveyed out of 476 who had 234 were sick children observed these children had had a cough at any time in the last 8 weeks showed 119 (58.9%) and then had an illness with a cough, did he/she breathe faster than usual with short, rapid breaths or have difficulty breathing 63 (33.7%) for less than two weeks 167 (89.3%) (Table 2) (Figures 2 & 3).

Table 2: Age categories and sex of the sick children in Ambo town, West Shoa Zone,Oromia Regional State, August 2020.

Place of Healthcare-Seeking Behaviour: The study revealed that out of 476 mothers enrolled in this study, 427(89.7%) reported their preference sources of health care seeking for childhood illnesses was health facilities whereas religious area was the second preferred next to health facilities 34(7.14%). Similarly, holy water 11(2.31%) and traditional healer 4(0.84%) were the least preferred sources of seeking by mothers/caretakers for their sick child, respectively (Table 3). Total of the 476 children, 234 (49.13%) who had been ill in the six weeks before the survey, any care was sought for 169 (72.22%) and 16 (6.84%) of ill children didn’t get any kind of help/care at home, traditional healer 10 (4.27%), holy water place 6 (2.56%), religious area 12 (5.14%) and Pharmacies 21(8.97%). Health centre, 169 (72.22%) were the most common sources where care was sought for the sick children. Furthermore, the main reason for visiting health facilities were condition worsened 152 (64.96%) followed by severity of disease 82 (35.04%) on the other hand the main reason for not visit health facilities were perception that the illness was not serious 34 (14.53%) followed by lack of money 7 (2.99%).Regarding time of health seeking after onset of the illness, among 234 mothers who sought care from health facilities, 135 (57.69) sought health facilities within first weeks after recognition of the illnesses, while 14 (5.99%) sought health facilities after two weeks. Of those, only 85 (36.32%) sought care within the first day after recognition of the illnesses, while for most sick children. This study also showed that on average time does it take to reach the nearest health facilities from mothers house, less than 30 minutes 349 (73.32%), 30-60 minutes on foot 123(25.84%) and greater than an hour on foot 4 (0.84), respectively (Tables 3 & 4).

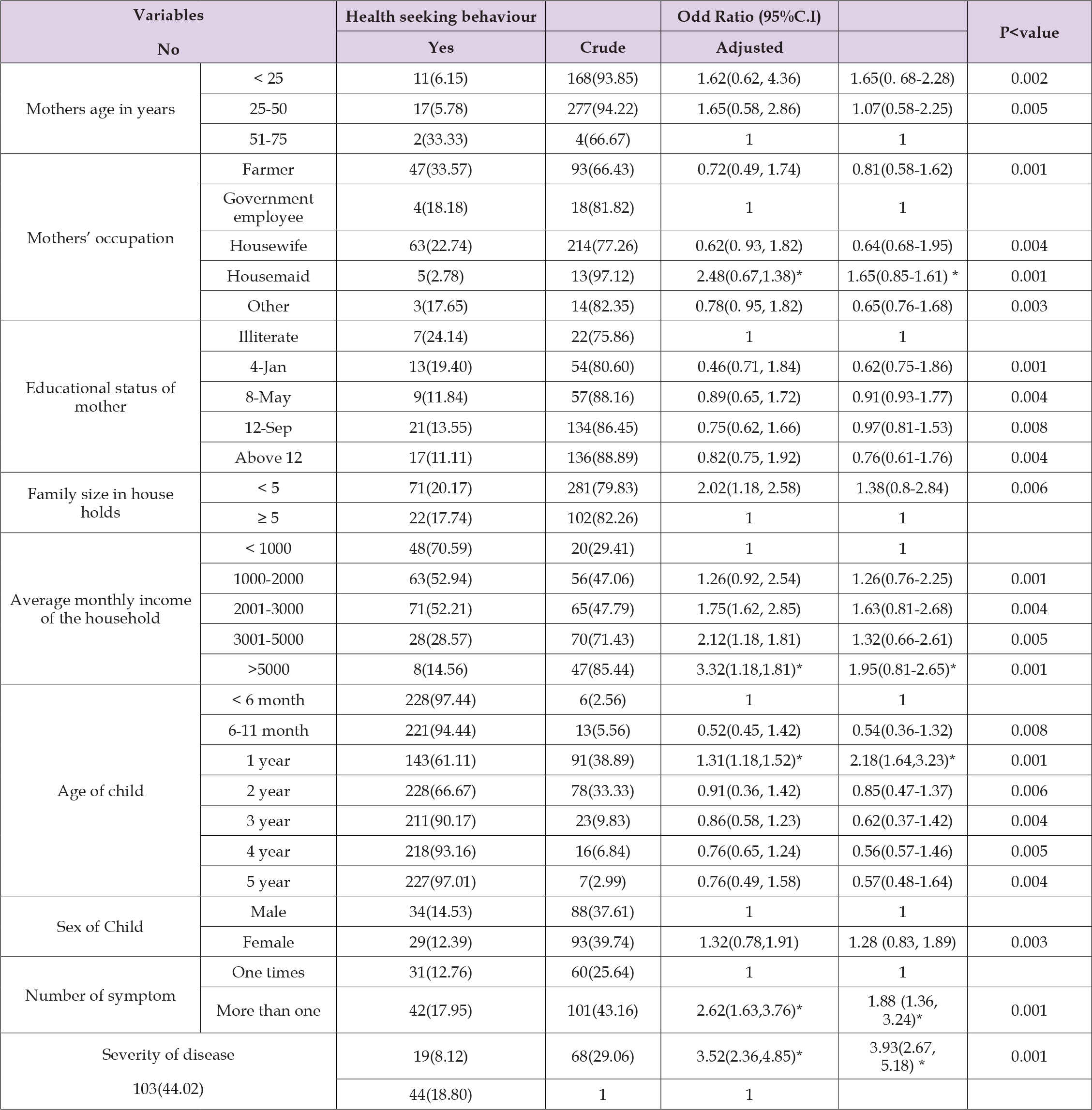

Bivariate and Multivariate Analysis: Bivariate and Multivariate logistic regression analysis were done to identify factors influencing modern health care seeking behavior for childhood illnesses in Ambo town. The results from the adjusted logistic regression analysis of factors associated with health care-seeking behaviour for under-five childhood illness after controlling for other factors, four factors had significant importance when it comes to appropriate healthcare- seeking practices in the Ambo town. The results showed that the adjusted logistic regression analysis of factors associated with health care-seeking practices for under-five childhood illness. The odds of seeking healthcare for childhood illness more likely higher when the child age is 1-2 years than age of the children more than 2 years and less than 1 years [OR 1.31; (95% C.I 1.18, 1.52)], [OR 2.18; (95% C.I 1.64, 3.23)], respectively. The study showed that, regarding to mothers age, those who were between 25-50 years more likely seek health care than 51-75 years [1.65(0.58, 2.86); 1.07(0.58-2.25)]. Concerning to educational status, the results showed no significantly difference among educational status of mothers (Table 5). Regarding to the occupation of the mother Housemaid were more likely seek health care than house wife [OR: 2.48 (95% C.I (1.65(0.85-1.61)]. Mothers who were earn more than 5000 birr per month more likely seek health care compared to who earn less than 5000 birr per month. [OR 3.32 (95% C.I (1.95(0.81-2.65)]. Age of mother and family size in the households had no significant association, but age of children had significant association among the factors.The result of multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that, severity of disease [OR= 1.88; 95%CI:(1.36, 3.24)] number of symptoms experienced by the child (OR=1.88; 95%CI: (1.36, 3.24)] were significantly associated with modern health care seeking for childhood illnesses. However, being sex of Child [OR=1.32; 95%CI: (0.78,1.91)] had no significant association after adjusted to the other variables (Table 5).

Table 5: Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with healthcare-seeking behaviour for childhood illness.

Note: *Statistically significant

The study revealed a response rate of 100% since out of 476 questionnaires that were given response. This result indicated that all the respondents were willing to respond to such questionnaires. Keeter [23] states that any survey with a response rate of above 70% gives out more reliable and accurate information as it manifests significant feedback. The objective of this study was to explore the healthcare-seeking practices of mothers of under-five children with childhood illness and to find out the socio-demographic factors and mother’s perception of causes of childhood illness, signs and symptoms of illness, severities of illness and treatment of illness associated with healthcare-seeking behaviour of the mothers, in Ambo town. From this study, 476 mothers were asked about the health status of the selected under-five children in the 8 weeks proceeding to this study. The overall 8 weeks prevalence of childhood illness that had one symptom of the disease was 91 (38.1%) and more than one symptom of disease was 143 (61.11%) when it compared with the study done at Bahir Dar and Ensero district [24]. The difference is due to the short recall time for childhood illness by the Bahir Dar study. In this study, 89.7% of mothers sought modern health care when their child got ill. This finding is similar to a study done in the Oromiya region of Ethiopia 87% [25] of mothers sought modern care. However, it is higher in a study done in Dangila town, north West Ethiopia 82.1% [26], and in North West Ethiopia 84.4% of mothers sought modern care [27], This difference may be due to differences in socio-demographic characteristics like: educational status, culture, economical status. In this study from a total of 234 sick children, the mothers reported different kinds of symptoms in the preceding 8 weeks. Among these, cough and fever 159 (67.80%), followed by cough, diarrhea and fever 137 (58.55%), fever only 135 (57.69%), cough and diarrhea 132 (56.41%), diarrhea and fever 130 (55.56%), diarrhea 129 (55.30%), with diarrhea and without diarrhea 55 (25.9%), and others 33 (14.10%) when this study compared with study done at Mekelle the most prevalent symptom were cough, diarrhea, fever, eye problems, skin infection and tonsillitis. Cough was the most common reported symptoms by 106 (18.9%) mothers [28].

Recognizing sever signs of childhood illnesses is an important factor that motivates mothers to take medical help. This study showed that mothers who did not perceive severe illness were less likely to seek health care than those mothers who perceived the illness as severe, in line with a systematic review in developing countries [29] as well as studies done in western Nepal [30] and Ethiopia [31,32]. The study showed that 427 (89.7%) mothers sought medical care from health institutions 14 (7.14%) from religious areas, 11 (2.31%) from Holey Water place, and 4 (0.84%) from Traditional healers, similar findings from a study done at Mekelle showed that 88% of the mothers who reported that they were sought modern medical care in the incidence of their children sickness reported [28].

Mothers who had children aged less than 2 years were more likely to seek appropriate health care compared to those with less than 1 year and older children. This is similar to studies in Bangladesh [33], rural Nigeria [34], rural Tanzania [35], Sub-Saharan Africa [36], and Ethiopia [32]. This might have been due to mothers’ understanding that children’s illnesses were more severe in younger compared to older children (> 1 year) [37,38]. In this study, income was not significantly associated with mother’s healthcare-seeking behaviour. This is inconsistence with studies conducted in a Nigerian Teaching Hospital [39], and a Tribal Community of Gujarat, India [40]. This might be due to the fact that, in the present study, income was not a barrier to seeking health care as services are provided free of charge for children under the age of five years. This study revealed that only nearly half 234 (49.13%) of participants sought health care for their children during common childhood illnesses. This is consistent with a prior study conducted in Northwest Ethiopia (48.8%) [41], but lower than a survey conducted in Nairobi (65%) [42]. The possible reason for the observed differences might be due to socio-demographic differences. This finding was also lower than the finding of a survey conducted in Bahir Dar (82.7%) [24]. Mothers who were aware of common childhood illnesses were more likely to seek health care than those mothers who were not. This is similar to the results of a systematic review conducted in developing countries [41].

In this study, distance from health institutions was not associated with seeking appropriate health care. This is in contrast to studies in rural Ensaro District, North Shoa Zone [24] in southwest Ethiopia [43]. The finding from the logistic regression analysis showed that mothers’ educational level had no significant difference among educational factors. This result was inconsistency with the study done in Ensaro District, North Shoa Zone, who reported that mothers who had educational level read and write, secondary education, and diploma and above were more likely to seek appropriate health care seeking behavior for childhood illnesses to health facilities than mothers who were illiterate [24]. In this study, family size was not significantly associated with health-seeking practices. The study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia was in agreement with this finding, and reported that family members having less than or equal to five members were four times more likely to seek healthcare for the sick child when compared to those having greater than five members [44]. Unlike wise, results in Tanzania showed that children from households having two to three under-five children were more likely to receive medical care late than those from households which had only one under-five child [45]. The study showed that healthcare seeking was related to particular illness symptoms and their perceived severity according to this finding. Mothers sought care from health facilities more frequently for diarrhea symptoms than cough and fever even more so when the diarrhea was accompanied by cough and fever. A similar finding was reported from Jaldu district, West Shewa zone, and rural Nigeria. This might be attributable to the perceived severity close to the illnesses.

This study concludes that a number of factors affecting health-seeking behaviour were identified. The critical predictors of healthcare-seeking identified using bivariate and multivariate analysis are mothers’ occupation, monthly income of the household, age of the child, number of symptoms, and severity of the disease. Awareness of common childhood illnesses perceived illness severity, perception of early treatment, and child age between 12-24 months were positively associated with mothers’ or caregivers’ healthcare-seeking behaviour. These findings suggest a need for interventions aimed at improving mother/caregiver awareness and perception of common childhood illnesses. Further, the findings implicate the Ambo town health office, healthcare professionals, and health extension workers as key stakeholders. The health office of Ambo town needs to pay attention to a number of factors affecting health health-seeking behaviour of the children that live in Ambo town. Efforts should be made by government and non-governmental organizations to improve the mothers’ health care-seeking behaviour by providing information.