Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Thomas Andrea Nkhonjera1*, Lydia Kishindo Mafuta2, Victor Kasulo3, David John Musendo4, Chrispin Botha1 and Atusaye Kyumba5

Received: February 14, 2025; Published: February 21, 2025

*Corresponding author: Thomas Andrea Nkhonjera, Department of Agri-Sciences, Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Mzuzu University, P/Bag, 201, Mzuzu, Malawi

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2025.60.009478

In Malawi, attending early learning in nursery school is not compulsory. However, the literature highly recommends the significance of early childhood education before they begin formal learning in primary schools, as it is believed that the school readiness process correlates with improved future academic performance in school. This study assessed factors influencing school readiness for children in Mzuzu City, from community-based childcare centres to primary schools. The study utilised a mixed-methods approach, gathering both qualitative and quantitative data. It specifically aimed to understand the perception and knowledge of teachers, parents, caregivers, and officials from governmental and NGOs regarding school readiness initiatives while exploring the challenges faced and evaluating the roles of various stakeholders in early childhood education. 100 participants were sampled, including teachers, caregivers, parents, governance committee members, and officials from government and NGOs involved with children’s transition process. Data were collected through in-depth interviews and self-administered questionnaires. Statistical and thematic analyses were conducted using SPSS version 29 and NVivo. Based on Amartya Sen’s capabilities theoretical framework, the study reveals that transitioning children from CBCCs to primary school helps them develop social competencies vital for adapting to the school environment. Challenges, including insufficient caregiver training, funding limitations, and poor communication hinder the school readiness process. The study emphasises addressing these issues to enhance children’s capabilities during this school preparedness and recommends transferring the Early Childhood Development Department to the Ministry of Education for better coordination.

Keywords: School Readiness; Transition; CBCCs; Governance Committees; Early Childhood Education; Caregivers; Parents; Teachers; Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach; NGOs

Literature on early education for children aged three to five acknowledges that kindergarten and primary school players must have the desire and positive attitude to eliminate the challenges and help every child have a smooth transition to school (Jolley, et al. [1]). However, limited research has been done to assess challenges linked to school readiness; neither knowledge nor perception of stakeholders is examined in detail.On the other hand, different studies highly recommend collaboration and networking among partners of community-based childcare centres and primary schools, including parents, caregivers, teachers, governance committee members, and government and non-governmental officials, who greatly influence smooth children’s transition to school (Bwezani, et al. [2]). However, the roles of these partners and policies in facilitating children’s readiness for school from community-based childcare centres have been given less attention. As such, the primary objective of this study was to evaluate the school readiness process for children’s education as they transition from community-based childcare centres to primary schools in Mzuzu, Malawi. To achieve this objective, the study focuses on three key areas. Firstly, it examined the knowledge and perceptions of parents, caregivers, governance committees, and teachers regarding school readiness initiatives that support children’s transition to primary school. This analysis provided insights into how different stakeholders understand and engage with early childhood education programs designed to prepare children for formal schooling. Secondly, the study explores the challenges associated with school readiness initiatives and their impact on children’s transition from community- based childcare centres to primary school. Lastly, the study evaluated the roles played by various stakeholders, including parents, teachers, caregivers, governance committees, government officials, and non-governmental organizations, in facilitating school readiness initiatives. It also considers the influence of early childhood education policies in enhancing or hindering these initiatives. To address these objectives, the study answered the following research questions: What are the knowledge and perceptions of parents, teachers, caregivers, and governance committees regarding school readiness initiatives? What challenges are associated with school readiness initiatives as children transition from community-based childcare centres to primary school? What roles do policies, parents, teachers, caregivers, governance committees, and both government and non-governmental officials play in facilitating effective school readiness initiatives?

In Malawi, sending a child to nursery school is not mandatory. However, the literature emphasises the importance of every child attending early learning before entering formal learning in primary schools, which is linked to better performance in school (Bhutta et al., 2019). Early education in Malawi begins at three years old and is completed at five in a nursery school, also called a community-based childcare centre (CBCC) (Bwezani, et al. [2]). At age five, a child transitions into formal learning in primary school. This transitioning process is also a school readiness initiative. The operation of the CBCC is regulated by the government of Malawi, with caregivers given the responsibility to nurture children and prepare them for primary education (De Witt, et al. [3]). At the same time, early-grade teachers are ready for the school readiness process to welcome children from nursery school. As such, school readiness initiatives are based on supporting schools and CBCCs to coordinate efforts to support children’s school transition. The key stakeholders in this coordinated effort are the parents, teachers, caregivers, governance committee members, and government and non-governmental officials (DeGrasse-Deslandes, et al. [4]). Although data on early childhood development in Malawi is not well gathered, it is believed that there are nearly 12,000 community-based childcare centres with a population of 1,123,468 children. The school readiness initiative hypothesises that children transitioning smoothly from community-based childcare centres to public primary schools tend to perform better in their education careers. Studies argue that early learning by children aged three to five contributes to good grades in their future academic journey (Greenwood, et al. [5]). Literature also highlights early childhood education partners, including parents, teachers, caregivers, policies, and government and non-governmental officials, who play significant roles in the readiness process for successful children’s transition to school (Jolley, et al. [1]). At the same time, scholars argue that whether a child attended lessons at kindergarten or directly entered primary school without prior lessons, both find the transition challenging (Liu, et al. [6]). As such, different studies suggest researching children’s transition process to understand the challenges, knowledge, and perception of partners and the roles played by these partners in advancing school readiness initiatives.

This study was guided by a theoretical framework developed by Amartya Sen called the capability approach. The capabilities theory focuses on the belief that development must shift from individuals’ economic capacity to empowering people’s capabilities in transforming their needs and the lives they value (Frediani [7]). The model emphasises that individuals’ capabilities must be tailored to empower their freedom and abilities to meet what they value and strive for. The benchmark of the theory triggers what people can do, called “functionings”, and what they can do, called “capabilities” (Hart, et al. [8]). Therefore, assumptions are based on four elements: capabilities, functionings, freedom and agency (Naz [9]). Firstly, the theory defines the difference between capabilities and functionings. Sen [10] describes capabilities as opportunities accessed and valued by individuals that they can achieve once exposed to resources and freedom. For example, for a child to perform mathematical skills in the school readiness process from a childcare centre to a public primary school, the necessary resources and environment to learn must be inclusive to meet their needs. These resources should come from discharges of different roles by parents, teachers, governance committees, caregivers, government, non-governmental organisations, and peers. Secondly, according to Saito [11], functionings are things individuals enjoy doing. Walker [12] mentions examples of functionings, including health, decent jobs, and education, which are linked and significantly impact people’s living conditions and standards. For instance, for a child to have a smooth transition to school from a childcare centre, the priority of the family budget toward the child’s education and health factors of every child is paramount. Furthermore, the agency in the capabilities theory assumes that individuals can bring about the change they desire based on their values and ambitions (Dang [13]). Hart, et al. [8] agree with this line of thinking, referring to agency as people’s capability to make individual choices based on aspirations and freedom. For example, for caregivers or teachers to promote school readiness, continuous professional development training is essential to enhance the agency of the caregivers in valuing and supporting children’s early learning.

The last element of Sen’s capabilities theory is freedom. Sen [14] describes freedom as the ability of people to make meaningful choices about their lives. Similarly, according to Naz [9], freedom covers the ability of people to achieve many valuable functions by overcoming the challenges that can hinder the achievement of capabilities and functionings. For example, school and childcare governance committees must ensure that children have access to formal schooling without barriers, such as decent infrastructure, which enhances children’s freedom to achieve education outcomes in class successfully. Amartya Sen’s capabilities theory directly links school readiness for children aged three to five. The theory considers the economic and social contexts and emphasises how income and resources translate into real opportunities for children’s education (Walker [12]). The model links the role of supporting the children’s transition process from childcare centres to the capability expansion of individuals (Sen, 2002). For example, Malawi’s early childhood development and education sectors aim to equip individuals with skills and knowledge beyond academic achievements, including social, emotional, and physical skills in children, which are the central line of thinking in the model (Ministry of Education, n.d). Furthermore, as the theory focuses on functionings, the school readiness process ensures that children are capacitated emotionally, socially, physically, and spiritually as the prominent domains of early learning functions as they transition to primary schools (Saito [11]). This suggests that for functionings to happen, collaboration and coordination of parents, teachers, caregivers, and governance committees to foster confidence, resilience, and a sense of belonging are paramount in school readiness. The last application of the theory is freedom and choices, which focus on ensuring that every child has an equal opportunity to access education regardless of their status, disabilities, or cultural and religious affiliations. Sen [14] defines this as child-centred education, where academic freedom is a right of every individual. Therefore, applying Sen’s capabilities and theoretical framework to school readiness is vital for promoting smooth children’s transition from community-based childcare centres. In this case, the model helps address the disparities in the school readiness process.

Scholars believe that early childhood education for children ages three to five impacts their performance when transitioning to primary schools from childcare centres. Due to this philosophy, many countries promote school readiness initiatives through early childhood development interventions. At the same time, scholars agree that the school preparedness process faces challenges affecting children and their parents, teachers, caregivers, governance committees, government and stakeholders, impacting the learning process and academic career outcomes (Bhutta, et al. [15]). The literature further agrees that the school readiness process and its challenges change at three stages of children’s formal learning. The first stage, argued by McCoy, et al. [16], happens at the individual level. This is the first stage in which a child has self-awareness of being a learner in the primary school setting from an early-day childcare centre. The second level is interacting with new friends in primary school, which differs from those in the community-based childcare centre. The last stage is the new learning curriculum of education, which is formal with new subject matters rather than playing in the daycare centre. Scholars assert that these changes provide an atmosphere different from a childcare centre’s requirements to a primary school for children and their parents, teachers, governance committees, and government and non-governmental organisations in terms of expectations and roles to be done (Greenwood, et al. [5]). In agreement, Pewa, et al. [17] sum up that in a school readiness process, all children face changes in the subjects they learn, expectations in performance by their parents and teachers, finding different new teachers as they start formal schooling, and demanding capabilities to transition smoothly. As such, it is hypothesised that a smooth child’s transition from preschool to school significantly contributes to their future class performance and socialisation (Reed [18]). Based on this hypothesis, school readiness has become a developmental agenda in both the global north and south. However, in Malawi, like any other country in Africa, sending a child of three to five years to nursery school is not mandatory as they transition to primary school from community-based childcare centres (Munthali, et al. [19]). Although early childhood development interventions are incorporated into Malawi’s policies, development agendas and strategic plans, the school readiness process still faces many challenges (UNICEF [20]).

Additionally, the literature emphasises that school readiness for children aged three to five from early childcare centres facilitates smooth adherence and promotes educational uptake in primary school without challenges (Neuman, et al. [21]). However, scholars and stakeholders in early education have different views of what constitutes school readiness. Brookfield [22] believes that school preparedness is a change where a child undergoes different environments of growth in their education career. Similarly, Moir, et al. [23] understand school readiness as a process where children move from the familiar, informal learning environment to an unfamiliar one where subjects, roles and expectations differ. However, this philosophy of school readiness does not critically clarify what the familiar and unfamiliar environment entails in the educational process, making it challenging to facilitate the smoothness of the transitioning process. Furthermore, research indicates that children face difficulties in school readiness based on their social status, family influence, disabilities and the learning environment with peers (Xu, et al. [24]). Likewise, Silo, et al. [25] argue that children face limited support by systems when transitioning to primary school. In agreement, Cunningham [26] recommends systematic collaboration, networking and dialogue among early learning stakeholders, including teachers, parents and caregivers, and governance committees, government and non-government organisations.

This suggests that all stakeholders must clearly define school readiness to facilitate collaboration and networking. As such, the researcher defines school readiness as a coordination process amongst early learning stakeholders, institutions and policies to promote the smooth running of childcare centres and primary schools. The hypothesis of school readiness for children ages three to five from preschool to formal education requires the participation of different early learning stakeholders. According to Tobin, et al. [27], these stakeholders include parents, caregivers, teachers, governance committees, schools, childcare centres, policymakers, governments, and non-governmental actors, who have different roles to play in facilitating smooth children’s transition. It is also believed that every stakeholder has a role in making the school readiness process successful and smooth for every child.

Scholars like Störbeck [28] argue that children’s parents are above all the stakeholders in the school readiness process because they make primary decisions concerning their children’s education. This is in line with a study on parent’s roles in children’s education, where it was found that parental engagement in the school readiness of their children processes positively impacts the learning outcome and attendance of children in school (De Witt, et al. [29]). Similarly, parental involvement was found to be a primary source of children’s academic achievement and self-esteem for social competence with peers in a study done by Fridani [30]. The daycare centre teachers, known as caregivers, are also stakeholders in early learning, successfully educating children to get into primary schools (Ye, et al. [31]). Munthali, et al. [19] argue that a caregiver is vital in caring for and preparing children for formal primary education. However, studies reveal many challenges caregivers face in discharging their duties (Munthali, et al. [19]). The study further indicated that apathy, lack of skills in handling learners, and lack of support from government and stakeholders are contributing factors to the challenges faced by caregivers. However, studies are limited to understanding caregivers’ perceptions and knowledge towards the school readiness process. Furthermore, the governance committees of schools and childcare centres are other critical stakeholders in promoting school readiness initiatives. Researchers agree that the quality of childcare centres impacts the school readiness process.

For example, Granone, et al. [32] conducted a study that found that children who attended good-quality childcare centres with good infrastructure and organised activities were more ready for formal learning in primary school than those who went to lower-quality centres. Additionally, primary schools and their teachers are major stakeholders in the school readiness process. DeGrasse-Deslandes [4] argues that the quality of primary school and its environment affect children’s capability to realign themselves to a new learning environment. This argument is also found in a study by Cunningham [26], who found that where teachers and their learners have a sound relationship, it positively influences their motivation, level of engagement, and academic attainment. Policymakers and agents of change in early learning education are key stakeholders who are critical in supporting children’s transition to school from childcare centres (Neuman, et al. [21]). Bipath, et al. [33] believe that policies supporting high-quality preschools, including adequate funding and regulations, help every child’s school preparedness. For example, a study in Malawi found that government-funded community-based childcare centres positively impact children’s transition to primary school (Bwezani, et al. [2]).

A study by McLinden, et al. [34] concluded that when the coordination between the school and a childcare centre is poor, the school readiness process is negatively affected, leading to anxiety, avoidance of school, stress, poor relationships among peers, slow adaptation to the school environment, poor academic performance and low self-esteem. Similarly, Macagno, et al. [35] highlight the critical challenges, including poor coordination between caregivers and teachers, change in curriculum and class set-up, limited parental involvement, and unskilled teachers and caregivers as significant school causes unpreparedness for all children. Therefore, this suggests the importance of involving various stakeholders and institutions in supporting a successful transition process for every child to excel in form learning. Globally, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) mandate the education policy framework in all United Nations territories. SDG number 4 gives autonomy to all nations to consider providing inclusive education to early children by 2030. This mandate advocates never leaving any child behind, regardless of gender, religious affiliation, disability, or race (United Nations [20]).

In both global north and south, school readiness has drawn the interest of different scholars and development agents in supporting its implementation in addressing the challenges children face in transitioning to school. Studies conducted in South Carolina comparing the formal and informal learning of children’s phonological and literacy concepts found that children who went through the formal childcare centres before transitioning to primary school performed better than those who did not attend (Reed [18]). An example of better performance was observed in writing their names, alphabet orders, and sound awareness. Similarly, Yim [36], in a study of children’s preparedness for school, observed that children who attended childcare centre interventions were more prepared to transition to formal learning than those who did not participate. Therefore, these findings suggest the importance of childcare centres in preparing all children for formal education to maximise improved performance. At the American College of Education in Northwest Atlanta, Georgia, a study focused on teachers’ views on blended learning and its consequences on learners’ performance. The findings revealed that blended learning positively impacts student achievement, including providing professional development skills to caregivers in childcare centres as a best practice in supporting school readiness for all children (Lloyd [37]). Similarly, a study by Lanahan at Marymount University in Arlington, Virginia, on caregivers’ skills to identify children with special needs found that they required professional development skills to support students with learning difficulties better (Lanahan [38]). Therefore, the findings suggest that the critical role of caregivers as major stakeholders in child education must be considered, along with the capacity to provide appropriate support to all children, as the school readiness process is deemed necessary.

Furthermore, a study in Africa at the Wits Centre for Deaf Studies revealed disparities in school preparedness initiatives, particularly for learners with disabilities. The disparities were highlighted in caregivers’ and teachers’ lack of skills to handle children aged three to five, lack of parental engagement, and poor communication between the informal and formal learning institutions (Störbeck [28]). A global study by different institutions from Africa, Asia, Europe and America recommended that world leaders prioritise inclusive early childhood development to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 4.2 (Olusanya, et al. [39]). This study observed several difficulties linked to access to education for children with disabilities, mainly in developing countries. The study further observed challenges of resource allocation schools towards readiness initiatives with shortfalls of existing policies supporting early education. The same disparities were observed by Clark, et al. [40] in South Africa and Kenya, where a policy- implementation gap with ideological misconceptions and a lack of resources were significant contributing factors to the challenges of poor school readiness among children. Furthermore, the University of West Georgia studied teachers’ perceptions of parental involvement. The study revealed that most parents lacked motivation to participate in their child’s education due to work schedules and limited access to technology. These were observed as significant hindrances affecting effective collaboration between the home and school (Cochran [41]). In line with this, Cunningham [26] provided recommendations such as regular updates between the school and home, conducting parent- teacher meetings, and utilising digital communication tools to address parental involvement challenges.

A study in China also revealed that when children transition to formal education, parents get stressed in many ways in supporting their children (Liu, et al. [6]). The study identified that parents’ level of education, the family’s socioeconomic status, and the handling of homework offered at home at school contributed to stress among parents. The study recommended the collaboration between the childcare centres and primary schools, providing educational guidance for parents and increasing community support through cultural and educational activities to advance smoothly in school. In Malawi, the study on community-based childcare centres indicated that the centres play an essential role in providing support for early learning, health services, nutrition, and safeguarding children (Munthali, et al. [19]). This study further identified challenges of inadequate caregiver training, dilapidated infrastructures and lack of financial support from the government, non-government and the community. Based on these findings, Jolly, et al. [1] suggested increasing caregiver training, building decent infrastructures, advancing community participation, and collaborations between government, non-governmental organisations, and communities to support a smooth transition of the children to school. In response to the mandate of Sustainable Development Goal number 4, which focuses on the provision of universal education to every child without discrimination, the Malawian government established the school readiness programme to promote smooth children’s transition from community-based childcare centres to public primary schools (Bwezani, et al. [2]). The programme is executed by the Ministry of Gender, Community Development and Social Welfare under the Department of Early Childhood Development. To implement the programme successfully, the country formulated national guidelines and legal frameworks to facilitate early childhood learning services.

These policies and frameworks include the early childhood development policy, early childhood strategic plan, advocacy and communications strategy, early learning standards and curriculum (Neuman, et al. [21]). Other development agencies, including UNICEF, Action- Aid and the Rodger Federer Foundation, also support the ministry in establishing community-based childcare centres. In addition, these early learning stakeholders train caregivers responsible for childcare centres and provide cooking utensils and playing materials (Munthali, et al. [19]). Furthermore, the childcare centres have a management committee providing governance and leadership to these centres. Even though this is the case, Sony, et al. [42] argue that there is no evidence on how these guidelines and community structures are effectively and efficiently operationalised to ensure maximum achievement of school readiness goals and objectives.

Malawi is one of the countries whose education system includes early childhood development and learning regulations are guided by the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) number 4. As mandated by United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 4, the Malawi government commits itself to providing inclusive education where all children, including those with disabilities, have equal access to education through the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (Lynch, et al. [43]). The Malawi government is committed to supporting school readiness initiatives by establishing national guidelines and legal frameworks to facilitate early learning standards. Soni, et al. [42] argue that these early childhood development regulations aim to foster inclusive services and quality assurance for every child in Malawi. However, the role played by individuals, including the policies, legal frameworks, and institutions in implementing these regulations to promote school readiness for every child from the daycare centres, has been given less attention in different studies. Evidence of the Malawian government’s political will to support education for all is the establishment of the Malawi Vision 2063 (MW2063). In the strategy, among the seven enablers, human capital development is achieved through all children’s mandatory participation in early childhood education. Jolly, et al. [1] argue that although this is the case, there are many disparities in implementing these policies. For example, the community-based childcare services at the centre are optional as the education policy mandates that the age of six be eligible for formal education in Malawi. Individual experience in early childhood education has shown that this affects even community-based childcare centre structures where the teachers are volunteers called caregivers, unlike in primary schools where the teachers are recognised as certified as professionals and paid civil servants by the government. Even though the government is moving towards certifying the caregivers as professionals and considering them on the payroll of civil servants, the implementation has many challenges that further disadvantage the school readiness process. Additionally, the set-up of early education for children aged three to five is under the Early Childhood Development Department in the Ministry of Gender, Community Development and Social Welfare, which has no mandate to provide education to Malawian citizens. The provision of education is mandated by the Ministry of Education and is guided by SDG 4 of the United Nations. These dynamics suggest an indication of challenges to the effort of the school readiness process. Secondly, Malawi has developed many strategies, including the Growth and Development Strategy (MGDS) III, which highlights several issues related to childhood education, such as expanding the improvement of infrastructures in childcare centres and primary schools. However, the MGDS does not provide an implementation plan and steps for achieving the strategy. At this level, it is the expectation of development agents and beneficiaries for the MGDS to make clear statements providing direction for supporting early learning as an indication of a serious commitment to developing human capital for future generations (World Bank [44]).

Furthermore, the national education policy recognises the importance of school readiness initiatives for formal education for all children in Malawi with key priorities. Mulungu [45] highlights the priorities of establishing new community-based childcare centres, recruiting new caregivers, and building the capacity of community members and stakeholders. The education policy is also believed to draw a leaf from other policies, such as gender, early childhood development, and the Constitution of Malawi, to support school readiness initiatives (Bwezani, et al. [19]). However, there is no empirical evidence of the same linkage at the implementation level of community- based childcare centres and primary schools. This gap indicates significant problems in institutional coordination in the school readiness process in Malawi. At the same time, Malawi’s early childhood development policy was developed in 2006 and is under review to incorporate emerging issues like children with disabilities and community participation and revised targets to be achieved (ActionAid, n.d). Therefore, this justifies the need for further studies to guide the government’s revision process.

This research was conducted in both nursery schools called community- based childcare centres and mainstream primary schools of Mzuzu city, where the CCAP Synod of Livingstonia Early Childhood Development Department, alongside the Malawi government with funding from the Rodger Federer Foundation, is implementing a school readiness program. The initiative started in 2020 and will end in 2029 with three phases of two years for each implementation phase.Mzuzu City is under the M’mbwelwa council of the Mzimba district. The city is in the northern part of Malawi and is an urban hub with a population of 221,272 people, comprising mainly the Tumbuka, Chewa, and Tonga ethnic groups (NSO [46]). It has 508 community-based and 313 private childcare centres. The city was in the pilot phase of the school readiness program before phase one implementation, which provided a benchmark for the study to assess school readiness. The district was among the first three districts piloted for the school readiness initiative under the early childhood development programmes in 1989 (Munthali, et al. [19]). This indicates the city’s experience executing early learning interventions linked to school readiness initiatives. Additionally, since 2020, the city, alongside its counterpart, the CCAP Synod of Livingstonia Early Childhood Development Department, have gained funding from the Roger Federer Foundation, including support of 3000 ECD kiosk kits, which are solar panels and batteries, as a pilot programme to promote successful transition process of children from childcare centres to primary school (ActionAid, n.d). An ECD kiosk has different technological tools with clear guidelines and curricula that facilitate participative learning in a child-centred approach through an element of the Know-How and Child Steps apps in an Android tablet phone (Roger Federer Foundation [47]). This system of promoting children’s transition in learning provided a benchmark for choosing Mzuzu City for the study to assess the school readiness philosophy in Malawi (Figure 1).

Scholars assert that research methods are categorised into interpretivism and positivism paradigms (Bryam, et al. [48]). This study adopted a mixed methods approach of interpretivism paradigm, which is qualitative and positivism, which is quantitative. The qualitative approach was chosen to listen to the voices and opinions of parents, caregivers, teachers, governance committees, and government and non-government officials. On the other hand, the quantitative approach validated the statistical information on the pattern of school readiness initiative challenges, perception, knowledge, and roles of the stakeholders in the early learning process.

This study has adopted a descriptive design. Cooper and Schindler [49] define descriptive design as a type of study which investigates individual opinions using an interview guide for data collection. Similarly, Trochim [50] agrees that descriptive design has systematic steps to be followed, from the collection of data to the analysis before a study conclusion can be drawn.

The population of the study is referred to by Creswell [51] as a group of people and objects or items that can be sampled for measurement to drive a conclusion. In this study, parents with a child at CBCC, teachers, caregivers, governance committee members, and government and non-governmental officials who play a role in facilitating children’s preparedness for school were the population of the research. Particularly, this study population was drawn from staff members of government and NGOs based in Mzuzu, including Mzuzu City Council Early Childhood Development Department, ActionAid Malawi, World Vision Malawi, CCAP Synod of Livingstonia Early Childhood Development Department and Rodger Federer Foundation as well as CBCCs and primary schools.

The researcher adopted a purposeful sampling framework. According to Saunder, et al. [52], this is a technique researchers consider when choosing participants from a population familiar with the phenomenon under study. Therefore, this technique fitted the research, as the objective was to assess individuals who have participated in the school readiness process and their knowledge, perceptions, roles, and challenges associated with preparing children for formal education.

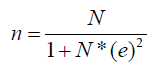

The researcher sampled 100 participants, both males and females, ages between 20 and 68, from Mzuzu city. This is based on the argument of Saunder, et al. [52] that sample size in business research varies depending on the statistical tests applied and recommends at least 100 responses for correlation studies. It is further argued that even 5 to 25 participants for qualitative research depend on the depth of the study (Creswell, et al. [53]). The recruitment process of the study participants was primarily based on engagement at both community-based childcare centres and primary schools within the school readiness program implemented by the CCAP Synod of Livingstonia Early Childhood Development Department. The 100 participants comprised 20 parents, 20 teachers, 20 caregivers, 10 NGO staff and 10 governmental officers with not less than a year of handling children aged 3 to 5 in their transitioning process to primary school or have experienced the transitioning initiatives. This sample size was determined using Slovin’s formula for a known population (Braun, et al.2020):

Where:

n is the sample size, N is the population size, and e is the level of

precision, with a 95 % confidence level and 5% precision.

The study involved collecting both qualitative and quantitative data using an interview guide with parents, teachers, caregivers, governance committee members, and government and non-governmental organisation officials. Bryman [54] refers to an interview guide that outlines semi-structured questions researchers use to collect data from research participants with a flexible approach to the themes. This research used face-to-face interviews with individuals for qualitative data, while self-administered questionnaires were used for quantitative information. The in-depth interviews were the only way of data collection because CBCCs and primary schools were close to the households of study participants, and bringing a group of parents, caregivers, or teachers to the centre for group discussions brought mobility and logistical challenges.

The descriptive analysis was conducted through the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 29 for quantitative data collected through a self-administered questionnaire. At the same time, the qualitative data collected through in-depth interviews was thematically analysed through NVivo to uncover reoccurring themes and patterns. All the collected data was stored in a safe and protected computer with a password known only to the researcher. At the same time, anonymisation of the analysed data from individuals used codes to replace the names of individuals.

Creswell and Creswell (2018) advocate for pilot testing of the research instruments. As such, pilot testing was done with a sample of teachers, caregivers, parents, governance committees, and government and NGO staff to ensure the tools were interpreted as intended and adequate before being administered to the sampled participants.

All ethical protocols were followed in this investigation. Before data collection, the Mzuzu University Research and Ethics Committee (MZUNIREC) provided ethical clearance (Ref No: MZUNIREC/ DOR/24/17). All participants provided informed consent, ensuring their voluntary involvement and the chance to withdraw at any moment. Pseudonyms were employed to hide participant identities, and unique identifying numbers in reports ensured data confidentiality. My positionality in this research was based on my open mindset to gather data as an academic researcher, regardless of my six years of work experience in early education for children aged three to five in different African countries, including Malawi.

This research focused on children aged three to five transitioning from a childcare centre to primary school. Therefore, the results of the study may not be suitable for applying to senior learners in primary and secondary schools or college-level education because the school readiness process is defined in the study as a coordination, networking and collaboration of parents, teachers, caregivers, governance committee members, government and NGOs officials in advancing successful transition of all learners from daycare centres to primary school. Additionally, the recommendations may not address factors affecting learners in upper classes or colleges but instead focus solely on improving the school readiness process for children aged three to five.

After analysing data from 100 respondents, the study results are discussed in thematic areas. The key themes include the roles, knowledge, and perceptions of parents, teachers, caregivers, governance committees, NGOs, and government staff in promoting school readiness. Furthermore, the challenges associated with the children’s transition process with alignment to Amartya Sen’s Capability approach are another theme in the discussion. Throughout the chapter, literature related to early learning initiatives in both the global north and south, including Malawi, is engaged.

Demographic Characteristics of School Readiness Process in Mzuzu City

Figures 2 & 3 below show that many parents (53.19%) were between 25 and 34 years old, and most (77.21%) were married, suggesting that children in two-parent households may have more stability in their transition to primary school. However, a noteworthy portion (14.95%) were single parents, which might indicate potential barriers to providing sufficient support for early children’s education (Figures 2 & 3). Figures 4 & 5 display the employment and education levels of parents. Nearly half (47.06%) were self-employed, while 26.72% were unemployed, reflecting possible financial instability, which is further supported by Figure 6 showing that 54.17% of parents earned less than 90,000 MWK per month. Despite these economic challenges, educational attainment among parents was relatively high, with over 84% having completed at least secondary education, which could positively influence children’s learning environments.

Knowledge of School Readiness among Early Child Education Stakeholders

The study observed that the definition of school readiness for children aged three to five years is generally based on a child’s developmental growth and academic graduation impacting children’s future school career attainment. This was observed by both Reeds [18,36] in their studies done in South Carolina and other parts of the global north, which showed the linkage between better academic results for children who attended childcare centres compared to those who did not. Similarly, Amartya Sen’s capabilities theory is of the same view that educational and developmental capabilities provide skills and knowledge to individuals, allowing them to function better in achieving their desired goals. Regarding teachers, the study findings show that school readiness is a movement of children from CBCCs to a primary school where formal education exists rather than playing and singing songs. They highlighted the need for parents, teachers, committees, government, and NGOs to meet the needs of children to love school jointly. “This is a movement whereby a child moves to a public primary school, where he or she no longer just plays but can read, write, and socialise as a sign of maturity.” (Teacher #, 05). This definition of the school readiness process aligns with parents’ views. Parents perceived school readiness as moving from a community-based childcare centre to formal learning taught by teachers, not caregivers. “School readiness is a process of helping children from CBCC entering primary school.” (Parent #, 04).“School readiness is about changing the place and type of learning in daycare to a place where a child mixes up with different age groups at primary school level” (Parent #, 12).Similarly, the governance committees of CBCCs and caregivers understand school readiness regarding children’s progression to school. They emphasised that this is observed in children’s ability to overcome challenges when entering standard one of their primary school.“We observe the academic uptake of a child. If they can interact with friends, memorise, and recite things, we are convinced the child is ready for grade one. This process is what we call school readiness.” (Governance committee member #, 06).“In my opinion, helping a child at CBCC to understand the nature of primary school before getting there is what I call school readiness. This makes life easier for every child in primary school to interact with friends.” (Caregiver #, 01). Government officials on early childhood development added that school preparedness is a continuous process that demands systematic planning and collaboration with different stakeholders to meet children’s needs and ensure their successful transition to school. “I can define school readiness as strengthening coordination and collaboration among stakeholders to support a child enter primary school without challenges.” (Government Officer #, 03). Although the knowledge of school readiness among early child education stakeholders is based on the developmental growth and educational performance of a child, this understanding undermines the need for a strategic, coordinated effort as per the ECD guidelines and policies for parents, teachers, caregivers, government and NGOs to address the challenges linked with school preparedness initiatives. This observation may support the hypothesis by Cunningham [26] that school readiness initiatives should not only be understood as developmental and educational growth but collaboratively and effectively strategically by all partners involved in promoting a smooth transition for every child.

The Perception of School Readiness Initiatives

The study’s results generally showed a positive perception of stakeholders towards early learning initiatives. According to the data, almost all the 100 interviewed study participants believed that children gain confidence and skills for primary school once they have undergone a childcare centre intervention. “I found the school readiness initiatives very beneficial to every child. Any child who participates in the early learning interventions copes well with new lessons in primary school.” (Teacher #, 12).“School readiness initiatives prepare a child to associate easily with others in primary school by removing fear and shyness.” (Teacher #, 07).“I have observed that any child from a daycare centre is more active in class activities and enjoys learning than those who did not attend early learning interventions (Teacher #, 05).These findings align well with Amartya Sen’s Capabilities model, which is based on creating the capabilities of individuals to choose the kind of life they desire with value (Sen [14]). Similarly, these results affirm Williams, et al. [55] observations that children who participated in childcare centre services faced fewer difficulties in primary school than counterparts who did not. Additionally, the parents had similar perceptions as teachers. They emphasised the benefits of CBCCs in nurturing children before getting into formal education. They believed that children who participated in the CBCC lessons had already acquired the learning skills needed most when starting grade one of primary education.“I am a living testimony to the beauty of CBCCs. I have witnessed how my child has performed in standard one because of his attendance at CBCC.” (Parent #, 20). “My child is performing well because I enrolled him at the CBCC before entering primary school. He is always among the top 5 in class.” (Parent #, 13). Opposite to other studies, one in Malawi observed that every child, regardless of whether they attended CBCC interventions or not, was found to have difficulties with school preparedness (Lyn, et al. [43]). The 20 caregivers and 20 governance committee members in this study had similar views of the teachers and parents that children who participated in nursery school activities had fewer struggles in their academic attainment.“The CBCC allows every child to visit the school even before starting standard one, helping them to socialise quickly with the school environment when they turn to grade one. Furthermore, they are taught to write and read certain words, including A E I O U, and when they enter standard one, they do not find this new.” (Caregiver #, 19).These study findings affirm the hypothesis that the school preparedness process is of great value in supporting smooth children’s transition that accelerates better performance, confidence, and socialisation among learners as they reach primary school (Soni, et al. [42]). Also, these results agree with a study by Munthali, et al. [19] in Malawi, where community-based childcare centres were paramount to every child’s success before starting their primary education.

Dynamics of Challenges Associated with School Readiness Initiative

Although the study observed many benefits of school readiness initiatives to children’s education, the results have also revealed many other challenges affecting the transition process. The major difficulties identified included limited allocation of resources to preschools, lack of skills and abilities by caregivers to execute their roles, and limited coordination among stakeholders to support smooth school preparedness for every child. These challenges affirm Amartya Sen’s Capabilities model, where external challenges are believed to impact individuals’ capabilities, limiting their freedom to achieve their desired goals. Firstly, teachers mentioned challenges with children’s poor performance because of new pedagogies and subjects in primary school compared to playing and singing at the CBCC. In connection, this challenge is further believed to be initiated by a lack of adequate teaching and learning materials with a dilapidated infrastructure of childcare centres. “During the rainy season, we fail to conduct sessions because the building we use is not fit to keep children when it is raining. We are afraid it may fall on them.” (Caregiver #, 01). A study by Liu, et al. [6] in China observed similar challenges where parents even faced anxiety and stress during their children’s transition to formal schooling. In agreement, parents’ concerns were based on the absence of school feeding programs in some schools other than the CBCC, where children were given porridge. The long distances to school, which some children cover from home, is another critical challenge mentioned. These challenges are believed to fall in the roles of parents’ capabilities on their socio-economic limitations. “Our children find it hard to adapt in primary schools mainly due to the absence of feeding program which is available in almost every CBCC.” (Parent #, 18).”Most children cover long distances to primary school compared to the nearby CBCC. This is one of the critical challenges most children face.” (Parents #, 15). The caregivers and governance committee members agreed to the challenges teachers highlighted affecting school readiness initiatives. School governance committee members believed that alignment with new teachers and new teaching methods in school compared to playing in CBCC is challenging for most children. In agreement, parents further believed the demand for uniforms, learning materials such as books, pens, and school development funds, and the lack of school feeding programs are major hiccups affecting school readiness initiatives. These results suggest that socioeconomic limitations affect family capabilities to meet the demands of school preparedness. “Most teachers in primary schools do not have early learning skills to support the incoming ones to feel welcome.” (Governance Committee member #, 12). “The challenge is that the school demands uniforms that most parents cannot provide. At the same time, there is a shortage of teaching and learning materials in most schools where children go to.” (Governance Committee Member #, 04). These results correlate with a study done in Malawi by Jolly, et al. [1], in which participants recommended systematic collaboration and partnerships to address the challenges of CBCCs and primary schools by considering the socioeconomic needs of parents.

Factors Accelerating Challenges of School Readiness Initiative

The study findings have revealed different factors contributing to the challenges of the school readiness process. Caregivers of CBCCs and teachers at primary schools acknowledged their lack of skills in handling early childhood education and lack of support from parents as significant factors affecting children’s preparedness for school. This research outcome relates to Amartya Sen’s capabilities model on institutional capabilities for providing support to individuals to acquire their abilities to meet their desired goals. While parents acknowledged their role in providing basic needs for children, including learning materials and moral support as they transition to school, they also blamed the government, schools, and NGOs for failing to support their children’s transition process. Poor classrooms in both CBCCs and primary schools highlighted their frustrations. “As parents, we make sure our children are prepared for both CBCC or school with the provision of food, uniforms and development funds, but the government does not consider building proper classrooms for our children, nor do NGOs focus their work on building decent classrooms.” (Parent #, 02). Similarly, governance committee members pinpointed the shortfalls of the government’s failure to provide adequate resources, which affected the efforts of parents, caregivers, and community leaders. “The government is the major contributor to the challenges. It fails to provide resources to ensure that all schools have a feeding program and built modern classrooms for children within reasonable walking distance.” (Governance committee member #, 09). The blame game between the community governance structures and government suggests the need for joint strategies and efforts to address these challenges. This aligns with the recommendation made in a study by Olusanya, et al. [39], where the stakeholders in early learning are encouraged to coordinate in advancing successful children’s transition to school.

Roles of Stakeholders in Supporting School Readiness Initiatives

Almost all 100 study participants highlighted in their responses that it is everyone’s responsibility to collaborate to support school readiness initiatives. “We have learnt that good collaboration, starting with parents, caregivers, teachers, governance committees, government and NGOs, is the best to achieve school readiness initiatives. So far, we have initiated a school readiness initiative network where all NGOs and government departments working on early education are members of this network.” (NGO Officer #, 08).“I feel our roles are different, but as parents, caregivers and committees, including government and NGOs, we all have a role to play. Therefore, we should prepare before school opens to buy all resources needed for our child and pay the school development fund in time to avoid disturbing our children’s education.” (Parent #, 01). The data reveals multiple roles and responsibilities each party, including parents, teachers, caregivers, committee members, NGO, and government, must play in supporting early learning. This includes preparing children for school, providing teaching and learning materials, and teaching them to attain skills and knowledge in their academic performance. However, this contradicts an earlier study by Munthali, et al. [19], where only caregivers were deemed the paramount role of supporting the transitioning process of children from childcare centres to primary schools. This suggests that most stakeholders, including parents, teachers, government and NGO officials, had little knowledge of their roles and responsibilities in school preparedness for all children. Therefore, the study findings by the researcher indicate progress and the landscape of collaborative effort that has been put in place to advance early learning for children aged three to five in Malawi. This is what Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach advocates for: an institutional framework with abilities that help expand an individual’s abilities to make informed decisions without cohesion. For teachers, academics and helping children master skills, including reading, writing and socialisation, were perceived as their initial roles and responsibilities. This is supported by Sustainable Development Goal number 4, as teachers are expected to support a smooth transition for all children in their early childhood and formal primary school education (United Nations [20]). Although this is the case, the study revealed various hindrances to the roles of teachers in promoting the transition process, including a lack of skills and limited resources for teaching children.“As we teachers, we do not have teaching and learning materials to help learners perform better. The government, which is supposed to make our work easy, is the worst as it stopped providing teaching and learning materials long ago.” (Teacher #, 02). Almost half of the parents who participated in the study, including #1, #2; #3, #4; #5, # 6; #10, #18; #19 and #20, considered bathing their children and feeding them before going to school, and delivering them at school as their prominent roles. They further highlighted giving them learning materials such as school uniforms and payment of school improvement grants. However, these results cast some doubts based on the challenges teachers and caregivers claimed associated with the lack of parental participation in their children’s education, such as being unable to prepare and coordinate with CBCCs and schools for their children’s successful transition.

As argued by Störbeck [28], parents are the primary duty bearer in supporting children’s preparedness for school; the study results challenge this notion by focusing on the collaborative effort of every party member involved in the process. Both caregivers and teachers proclaimed that they also play a primary role in early childhood education as they nurture and educate foundational skills in children. They claim that their roles are even deemed the most critical in fostering children’s self-esteem and social and academic skills, which are influential in successfully transitioning every child to school. However, both parents and governance committee members refuted the claim by caregivers, emphasising that all parties involved in the school readiness process have failed a child, highlighting many challenges associated with their capabilities to execute individual roles, including low qualifications, lack of skills to handle children and limited motivation as most of them work as volunteers. The governmental officials defined their role in the school readiness process as coordinating early learning activities, policy implementation, and lobbying for other partners to participate in creating an environment safe for every child to learn. Although this is a designed role in the guidelines of ECD in Malawi, the study observed challenges in implementing the policies, including a lack of funding and a disjointed effort by development agencies. “It is always difficult for us to monitor activities in CBCCs and primary schools because of limited resources, yet our development counterparts in the NGO sector are always in the schools. Yes, we have a good working relationship. However, the coordination part is somehow a challenge. At the same time, we have few partners interested in supporting the ECD activities in the district.” (Government Official #, 03). These findings, therefore, provide hope for a collaborative approach to supporting school readiness initiatives if only a systemic plan can be instituted by the governing body under the district council’s leadership.

Possible Solutions to Challenges of School Readiness Initiatives

The study findings proposed solutions to the challenges of school readiness initiatives. Firstly, teachers advocated for collaborative approaches and initiating activities that motivate learners to remain in school, such as school feeding programs, income-generating activities, and joint meetings between the school and CBCC. These solutions align with Amartya Sen’s capabilities model of empowering individuals to take charge of their development (Sen, 2002). For parents, community engagement in the form of village banking and period meetings with teachers and caregivers were deemed the best strategies to address the challenges of their children’s school readiness. “We have already started an income-generating activity through village banking for all parents at our CBCC, which helps with financial challenges. If this can be scaled up to other CBCCs and schools, I believe some challenges can be addressed without heavily relying on external support” (Parent #, 02). Caregivers and governance committee members insisted on continuous professional development training to improve their skills in handling children, systematic resource allocation by the government and donor support, and the establishment of other CBCCs, particularly in rural locations. “Most of our caregivers need to be trained if we are to help our children successfully prepare for school. These training sessions are fundamental, as the primary school syllabus keeps changing. Therefore, they must continue learning to sharpen their knowledge on the new subject content to prepare the children well for school.” (Governance committee member #, 08). These proposed solutions align well with the Malawi Development Growth agenda, notably on early childhood development and education, as community participation, resource provision, and professional development are significant strategies for successfully transitioning children to school (Soni, et al. [42]).

The study’s mixed-methods approach of qualitative and quantitative methods revealed a positive attitude of early education stakeholders towards school readiness initiatives, with defined roles expected by key players in children’s transition to school. Almost all 100 participants in the study agreed on the significance of collaboration among all stakeholders in advancing smooth children’s transition to primary school from the childcare centre. Although all 100 study participants agreed that attendance at nursery school services is important for every child’s better school performance, numerous challenges existed, including a shortage of funding, unqualified caregivers, poor coordination, and low parental involvement in school readiness initiatives. However, the study observed that both the school and CBCC players believed in collaboration efforts to solve the challenges for the betterment of children’s school preparedness. Furthermore, the study participants suggested training caregivers, continuous professional development to teachers, allocation of funds to CBCC and school, and having a solid school readiness coalition among all the parties involved as key recommendations in addressing the challenges affecting children’s transition. Therefore, as assumed by Amartya Sen’s Capabilities model, this strategic coalition means of addressing the school readiness challenges can enhance children’s abilities, freedom and opportunity to transition to primary schools and attain future educational achievements successfully [56-70].

Based on study results, it is essential to transfer the Early Childhood Development Department from the Ministry of Gender, Community Development and Welfare to the Ministry of Education in Malawi to enhance caregiver training and improve resource allocation. This shift would foster coordinated educational interventions, recognising CBCC services’ critical role before primary school enrolment. Additionally, integrating the ECD Department with the Ministry of Education could also address caregiver training challenges through Teacher Training Colleges the ministry has nationwide. This can be done by introducing an ECD curriculum, which can enhance support from the government and NGOs, ensuring caregivers receive formal training alongside primary school teachers. This could motivate caregivers to transition from voluntary to professional positions in childcare centres. Furthermore, as the ECD policy is under review, it is recommended that Malawi’s review incorporate strategies for enhanced stakeholder engagement and communication. This will address gaps and support a smoother transition for children between community- based childcare centres and primary schools. Lastly, almost all the 100 study participants suggested the need for continuous professional development for caregivers and teachers, urging further research to establish its impact on facilitating school readiness initiatives.