Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Juan Luis Ignacio-de la Cruz and Juan Manuel Sánchez-Yáñez*

Received: January 16, 2024; Published: February 11, 2025

*Corresponding author: Juan Manuel Sánchez-Yáñez, Environmental Microbiology Laboratory, Institute of Chemical Biological Research, B-B3, University City, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolas de Hildalgo. Francisco J Mujica S/N, Col Felicitas del Rio ZP 58030, Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico, syanez@umich.mx

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2025.60.009466

In Phaseolus vulgaris production it is important to regulate the application of NH4NO3, by inoculation with Azotobacter vinelandii and Bacillus licheniformis plus multi-wall carbon nanotubes (MWCN), to decrease the release N2O from NH4NO3 a greenhouse gas, according to soil physical and chemical properties under P. vulgaris cultivation. The objective of this work was to analyze the response of P. vulgaris with A. vinelandii/B. licheniformis with NH4NO3 at 50% plus MWCN. For this, P. vulgaris seeds were treated with a mixture of A. vinelandii and B. licheniformis and 50% NH4NO3 plus 10 or 20 ppm of MWCN, by the response variables: germination percentage, phenology and seedling biomass, the experiment was carried out under a random block: P. vulgaris fed with 100% NH4NO3 uninoculated, non-MWCN or relative control; P. vulgaris non NH4NO3, uninoculated, irrigated only water or absolute control; the treatments: P. vulgaris with A. vinelandii and B. licheniformis 50% NH4NO3 plus 10 or 20 ppm of MWCN, individually and in mixture. The experimental data were analyzed by ANOVA Tukey (P<0.05). The results showed that P. vulgaris with A. vinelandii/B. licheniformis with 50% NH4NO3 plus MWCN, germinated better and faster, positive response of P. vulgaris was also observed on the phenology and biomass of P. vulgaris, compared to P. vulgaris plus 100% NH4NO3, uninoculated. The results support that the positive effect of A. vinelandii /B. licheniformis, inside the root system of P. vulgaris due to transforming organic compounds, from root metabolisms into phytohormones, to enhance 50% NH4NO3 uptake. This root activity of P. vulgaris was improved by combination of A. vinelandii /B. licheniformis by the MWCN, that accelerated and optimized 50% NH4NO3 uptake, consequently there was not NH4NO3 remaining, in that sense, to reduce greenhouse gas generation compared to 100% NH4NO3 uptake in uninoculated P. vulgaris, when non-uptake of NH4NO3 caused release of NO3- with subsequent generation of N2O, reason is why to decrease NH4NO3 with A. vinelandii /B. licheniformis plus MWCN are, important to mitigate the impact of greenhouse gases on P. vulgaris production, also to preserve soil fertility and prevent surface and groundwater pollution by overfertilization.

Keywords: Soil; Overfertilization; Loss of Fertility; Beneficial Plant Bacteria; Carbon Nanoparticles; NH4NO3 Optimization; Greenhouse Effect Mitigation

Currently, the generation of greenhouse gases in the production of Phaseolus vulgaris causes global warming, due to over nitrogen fertilization with NH4NO3,that caused N2O from NO3 under common environmental conditions during P. vulgaris cropping [1], reason is why strategies are proposals, that combine the reduction of the NH4NO3 dose, without risk of compromising healthy plant growth, as well as to inoculate P. vulgaris seed with Azotobacter vinelandii with B. licheniformis, genera of endophytic plant growth bacteria [2,3], that optimize nitrogen fertilizer to the maximum, through the synthesis of phytohormones, to induce maximum activity of the root system that uptakes NH4NO3 action [4,5], that can be improved by applying multi-wall carbon nanotubes or MWCN [6], non-toxic for plants, animals or human beings [7], that accelerate the action of bacterial phytohormones [8], so that NH4NO3 is consumed in such a way, that there is no remaining NH4NO3 [9], that generates N2O from NO3 greenhouse gas that causes global warming [1]. There is evidence that the combination of seed with genus of plant growth promoting bacteria genera, mixing with MWCN can prevent the loss of soil fertility, due to excess NH4NO3 non uptake by the root vegetal system [9-15]. Therefore, the objective of this work was to analyze the response of P. vulgaris with A. vinelandii and B. licheniformis, NH4NO3 at 50% plus MWCN to reduce N

The genera of plant growth-promoting endophytic bacteria: A. vinelandii and B. licheniformis are part of the bacterial collection of the Environmental Microbiology Laboratory of the Research Institute, and were isolated from the interior of roots of Zea mays var mexicana (teocintle); A. vinelandii was grown in Burk broth while B. licheniformis was grown in nutrient broth to inoculate a dose of 1.0 x 106 CFU/ml/0.5 g of P. vulgaris seeds individually and in a mixture of 0.5 ml of each to have the dose 1.0 x 106/ml/0.5 g of P. vulgaris seed [15]. The seeds of P. vulgaris var canario were obtained from the Secretariat of Livestock and Hydraulic Resources and Environment, Mexican government delegation, Michoacán, México. The MWCN were acquired from Sigma-Adrich; were suspended in saline solution (0.85% NaCl and 0.01% commercial detergent, sterile by autoclave), applied to the P. vulgaris seed at doses of 10 and 20 ppm [16]. The response variables used to evaluate the response of P. vulgaris with 50% NH4NO3 with A. vinelandii and/or B. licheniformis, plus carbon nanotubes were: germination percentage, seedling phenology: plant height (PH), root length (RL), fresh and dry aerial and root weight (AFW/RFW/ADW/RDW). The experiment was carried out under a random block design with P. vulgaris fed with 100% NH4NO3 uninoculated or relative control, P. vulgaris non NH4NO3 irrigated only with uninoculated water or absolute control and the treatments: P. vulgaris with A. vinelandii and B. licheniformis 50% NH4NO3 with 10 and 20 ppm of MWCN, individually and in mixture with and without MWCN, P. vulgaris with 50% NH4NO3 uninoculated with 10 ppm of MWCN. The experimental data were analyzed by ANOVA Tukey [17]. On Figure1 show scheme of the experimental design to evaluate the response of P. vulgaris with 50% NH4NO3 with A. vinelandii and/or B. licheniformis plus MWCN.

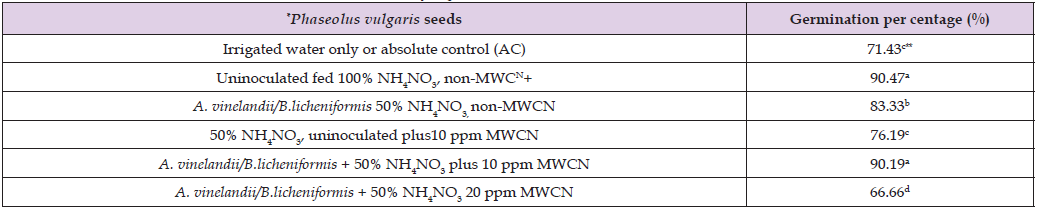

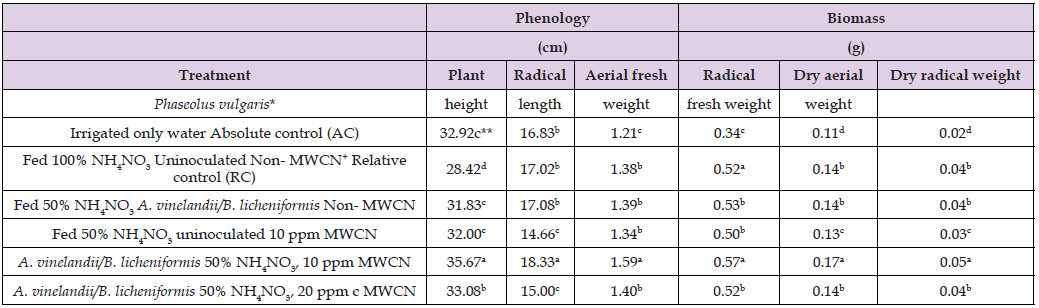

Table 1 shows the effect of A. vinelandii and B. licheniformis on the germination of P. vulgaris seeds, with 50% NH4NO3 and 10 or 20 ppm of MWCN. A germination percentage of 71.43% was registered in P. vulgaris, irrigated with water or AC alone, a statistically different numerical value compared to 90.47% of P. vulgaris with 100% NH4NO3, non- MWCN, in contrast to the value of 83.33% germination in P. vulgaris with A. vinelandii, 50% NH4NO3 plus 10 ppm of MWCN: numerical value with statistical difference compared to 76.19% in P. vulgaris with 50% NH4NO3, uninoculated plus 10 ppm of MWCN; by germination percentage, that was also statistically different compared to the 90.19 % in P. vulgaris, with A. vinelandii / B. licheniformis and NH4NO3 at 50% plus 10 ppm of MWCN, in evident contrast with the germination percentage registered for P. vulgaris and A. vinelandii/B. licheniformis at 50% NH4NO3, plus 20 ppm of MWCN, with a value of 66.66%. According to this results, 3 fundamental facts can be inferred. First, that the germination of P. vulgaris with NH4NO3 at 50% alone, was equal to germination of P: vulgaris at 100% NH4NO3, with the combination of A. vinelandii / B. licheniformis, plus 10 ppm of MWCN [18]. Second to increase germination that P. vulgaris was only possible with A. vinelandii and B. licheniformis plus 50% NH4NO3 [19]; because individually neither of the two bacterial genera reached a higher percentage of germination, including at seedling stage (data not shown). Third that although MWCN increase and accelerate the production of phytohormones associated with germination [20], only if the concentration is not greater or less than 10 ppm, because as it was not registered when 20 ppm was applied germination was reduced, due to negative effect both on the seed of P. vuglaris and on the beneficial phytohormonal activity of A. vinelandii / B. licheniformis [21,22]. Table 2 shows the effect of A. vinelandii and B. licheniformis on P. vulgaris with 50% NH4NO3 plus 20 ppm MWCN, on the phenology and biomass of P. vulgaris at the seedling level, where a plant height (PH) of 33.08 cm was registered, a statistically different value compared to 28.42 cm HP of P. vulgaris uninoculated, with 100% NH4NO3 or RC, a numerical value with statistical difference compared, to 35.67 cm HP of P. vulgaris with A. vinelandii/B. licheniformis at 50% NH4NO3, plus 10 ppm MWCN. This value was statistically different compared to 31.83 cm PH of P. vulgaris at 50% NH4NO3, A. vinelandii/B. licheniformis non MWCN, compared to the PH of P. vulgaris used as relative control (RC), also with the 32.92 cm of uninoculated P. vulgaris, non NH4NO3 or neither MWCN. While the root length (RL) of P. vulgaris was: 18.33 cm with A. vinelandii and B. licheniformis plus 10 ppm of MWCN, a statistically different value compared to the 15 cm RL of P. vulgaris with A. vinelandii / B. licheniformis 50% NH4NO3, with 20 ppm of MWCN and the 14. 66 cm RL of P. vulgaris with A. vinelandii / B. licheniformis, 50% NH4NO3 non- MWCN, a statistically different value compared to the 16.92 cm RL o0f P. vulgaris non NH4NO3, uninoculated, or neither MWCN, used as absolute control (AC).

Table 1: Effect of A. vinelandii/B.licheniformis at 50% NH4NO3 plus MWCN+ on the germination of Phaseolus vulgaris var Canario.

Note: *n= 50 **Values with different letters had statistical difference (P<0.05) according to ANOVA-Tukey. +MWCN= multi-wall carbon nanotubes.

Table 2: Effect of Azotobacter vinelandii and Bacillus licheniformis on growth of Phaseolus vulgaris at seedling stage at 50% NH4NO3 plus multi-wall carbon nanotubes (MWCN)+.

Note: *n = 6 **Values with different letters had statistical difference (P<0.05) according to ANOVA-Tukey.

In relation to biomass such as fresh and dry aerial and radical weight (AFW/RFW/ADW/RDW), the highest was registered in; P. vulgaris with A. vinelandii /B. licheniformis and NH4NO3 at 50% plus 10 ppm of MWCN, were registered 1.59 g of AFW 0.57 g of RFW, 0.17 g of ADW and 0.05 g of RDW values with statistical difference compared to the values of P. vulgaris with NH4NO3 at 100% uninoculated or neither MWCN with: 1.38 g of FAW, 0.52 g of RFW, 0.14 g of ADW and 0.04 g of RDW; these values were statistically different from those registered in P. vulgaris with A. vinelandii / B. licheniformis with NH4NO3 at 50% non- MWCN with: 1.39 g of AFW, 0.53 g of RFW, with 0.14 of ADW and 0.04 of RDW, these values were also statistically different to P. vulgaris uninoculated at 50% NH4NO3 plus 10 ppm MWCN, 1.34 g AFW, 0.50 g RFW with 0.13 g ADW and 0.03 g RDW. It was evident that all these numerical values were different from those registered in P. vulgaris uninoculated, neither NH4NO3, non- MWCN irrigated only with water with 1.21 g AFW, 0.34 g RFW as well as 0.11 ADW and 0.02 RDW.

These results support several obvious facts. First is that the uptake capacity of NH4NO3 by P. vulgaris roots for the 100% dose is limited, or excessive, because even 50% of NH4NO3 is required for the beneficial phytohormonal activity, in P. vulgaris roots of A. vinelandii in synergic action with B. licheniformis to be optimized (4,5:10,11), and avoid the release of NO3 with the possibility of generating N2O (1,2:12,13). Second is that MWCN have a positive effect, on the water and mineral uptake mechanism that initiates germination and favors the uptake of NH4NO3 at 50%[14,16,23], according to the concentration of the MWCN a positive effect better with 10 ppm than with 20 ppm MWCN [23-25], that is associated with the possible toxicity in the metabolism of seeds and roots of P. vulgaris [21,22]. Third is that if the seeds are inoculated with A. vinelandii and B. licheniformis it is induced, the growth promotion effect on the germination of P. vuglaris, is accelerated and improved, allowing the optimization of the 50% NH4NO3 dose [26-28], to prevent the release of NO3 into the soil to avoid the generation of N2O, as well as the loss of organic matter, as well as the contamination of surface water and groundwater [1,2,10].The results registered on the germination and growth of P. vulgaris with 50% NH4NO3, support the potential of MWCN, to solve problems associated with the dynamics of NH4NO3 in plant roots [29,30], as well as the real possibility that MWCN, can be used as part of an integral strategy for sustainable agriculture with plant growth promoting bacteria [26,27].

It is concluded that the combination of A. vinelandii and B. licheniformis, at dose of 50% NH4NO3 in P. vulgaris, can be improved with MWCN, under the premise of finding the minimum concentration sufficient, to optimize the uptake of NH4NO3, without risk compromising the healthy growth of the legume, or the environment by preventing the loss of soil fertility, the contamination of surface water and groundwater, as well as the release of N2O to mitigate global warming due to cultivation of P. vulgaris.

To the Coordinación de Investigación Científica de la UMSNH “Aislamiento y selección de microorganismos endófitos promotores de crecimiento vegetal para la agricultura y biorecuperacion de suelos” from the Research Project 2.7 (2025), Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolas de Hidalgo, Morelia, Michoacán, México.

“Field Test of a Living Biofertilizer for Crop Growth in México” from Harvard University, Cambridge, Ma, USA (2021-2024) with support of Rockefeller fund, and to Phytonutrimentos de México and BIONUTRA S, A de CV, Maravatío, Michoacán, México for the P. vulgaris seeds and verification of greenhouse tests. To Jeaneth Caicedo Rengifo for her help in the development of this research project.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.