Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Juliana Teixeira Dutra1*, Fabrício Antônio Ferreira Martins2, Juliana Meireles da Silva2, Alexandre Rodrigues3 and Moisés Palaci1

Received: January 15, 2025; Published: January 27, 2025

*Corresponding author: Juliana Teixeira Dutra, Núcleo de Doenças Infecciosas, Centro de Ciências da Saúde (Health Sciences Center), Universidade do Espírito Santo. Av. Mal. Campos, 1468 - Santa Cecilia, Vitória - ES, CEP: 29047-100, Brazil

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2025.60.009442

In December 2019, pneumonia cases of unknown origin were identified in individuals working or residing near the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan, China. Sequencing of respiratory samples revealed a novel coronavirus, initially named 2019-nCoV, now known as SARS-CoV-2. The viral genome encodes key proteins including those involved in replication (Rep 1a and Rep 1b) and structural proteins (S, E, M, N). Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) emerged as the gold standard for COVID-19 diagnosis, amplifying specific regions of the virus’s genetic material to estimate viral load using cycle threshold (Ct) values. However, RT-PCR’s accuracy is influenced by factors such as sample collection, storage, and timing of testing. This process includes mRNA amplification via extraction of viral RNA from respiratory samples using commercial kits. RNA extraction, a crucial step, significantly impacts the accuracy of subsequent analyses, with growing demands for reliable and automated extraction kits. The quality of RNA is paramount, but accessibility remains a challenge in lower-resource settings. This study aims to optimize a simple RNA extraction and viral inactivation method, evaluating factors such as freezing, agitation, and protease treatment to enhance the sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in nasopharyngeal swabs. The findings propose a simplified alternative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA extraction and purification.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2; RT-PCR; RNA Extraction; Viral Inactivation; Diagnostics; Cycle Threshold; Nasopharyngeal Swabs; Viral Load; COVID-19; RNA Inactivation

In December 2019, several individuals who worked or lived at the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, developed pneumonia of unknown origin [1,2]. Sequencing analysis of respiratory samples identified a new coronavirus, initially named 2019 novel coronavirus (2019- nCoV) and now known as SARS-CoV-2 [3,4]. The viral genome encodes several essential proteins, including the Rep 1a and Rep 1b regions involved in viral replication, and the S, E, M, and N regions, which code for structural proteins [5,6]. Real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (real-time PCR or RT-PCR) has become the gold standard for diagnosing COVID-19 [7,8]. The RTPCR process amplifies well-defined regions of the virus’s genetic material, multiplying those thousands of times. This amplification generates sufficient material to be identified, resulting in cycle threshold (Ct) values [9,10]. Ct values in COVID-19 RT-PCR tests provide an estimate of the viral load in biological samples [11,12]. However, the RT-PCR method has certain limitations, and its accuracy depends on variables such as proper sample collection and storage, the timing of the test relative to the infection window, internal validation, and cases where the absence of genetic material amplification does not necessarily exclude infection [12-14]. For viruses like SARS-CoV-2, mRNA amplification is performed by collecting respiratory samples from the person being tested, followed by the extraction of genetic material using specific commercial kits [7,8].

The RT-PCR process involves several steps, including the extraction of viral RNA from the clinical samples collected [9,10]. The first step, RNA extraction, is critical for COVID-19 detection as it determines the quality of RNA used in subsequent analysis. Throughout the pandemic, there has been a growing demand for reliable commercial kits designed for automated SARS-CoV-2 RNA extraction [8,15]. The quality and quantity of RNA are key factors as they directly influence the accuracy of gene expression analysis and other downstream RNA- based applications [16,17]. High-quality RNA is essential for reliable results, but the COVID-19 emergency has highlighted the inaccessibility of many advanced kits and equipment in low-complexity laboratories and developing countries [18,19]. The goal of this study is to optimize a simple RNA extraction and viral inactivation method for use in SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics [20-23]. In this study, we evaluated the influence of various factors — such as freezing, agitation, and protease treatment — on the sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in clinical samples (nasopharyngeal swabs [NPS] from clinically suspected COVID-19 patients) and ultimately aimed to propose a simple alternative method for viral RNA extraction and purification [24-30].

PICO Strategy

The PICO strategy was employed to simplify the research question. This methodological tool is widely used to formulate research questions clearly and objectively, particularly in the fields of health and evidence-based medicine [31-33]. The acronym PICO stands for four main elements: P (Patient or Problem), I (Intervention), C (Comparison), and O (Outcome). In this study, the element (P) was defined as patients with clinical suspicion of COVID-19 at the Local Laboratory; (I) represented samples that underwent the SARS-CoV-2 inactivation process; (C) referred to samples that underwent the process of genetic material extraction for the SARS-CoV-2 virus; and (O) aimed to assess the impact of this inactivation on RT-PCR results. The research question established was: “Does the virus inactivation method positively influence the diagnosis of COVID-19 using the RT-PCR technique?” This question guided the methods used in this research. Five laboratory tests were conducted (Figure 1).

Pre-Laboratory Tests

Nasopharyngeal secretion collection is a medical procedure used to obtain samples from the upper part of the throat behind the nose (nasopharynx). It is commonly performed for diagnostic purposes, especially to detect respiratory infections such as SARS-CoV-2, influenza, and other pathogens [34-36]. Samples of nasopharyngeal secretions were collected using sterile rayon swabs to obtain secretions from both nostrils of patients with suspected signs for COVID-19. After collection, the swab was immediately placed into a 10 mL polypropylene conical tube containing 2 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride, following the established protocol for routine use at the Local Laboratory [37-40]. The swab samples were rinsed in approximately 2 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride, vortexed, and 200 μL aliquots of the samples were transferred into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes. Aliquots were prepared at all stages of the laboratory tests to ensure sufficient material was available for each step of the testing process [41-45].

Diagnostic Testing for COVID-19

Patients with suspected signs for COVID-19 are tested for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 using real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from nasopharyngeal secretion samples [8,28,45,46]. Swab samples collected must be promptly transported to designated laboratories, where RNA is properly extracted. Detection is performed using RT-PCR with primers and probes specific to the target sequences. In tests 01, 02, and 03, after arriving at the laboratory, the viral material was extracted using the local laboratory’s gold standard method, the “Pure Link Viral RNA/DNA Mini Kit (Cat. No. 12280050, Invitrogen, USA),” following the guidelines provided in the manufacturer’s manual [31,47].

Sample Conditions

Step 1 (Alternative Procedure for Storaging Samples): during routine practice at the local laboratory, nasopharyngeal swab samples were processed immediately upon arrival and kept at room temperature throughout all processing stages. These samples were stored in a refrigerator only during the RT-PCR amplification and analysis period and were reused only in cases of experimental failure. Based on the established knowledge that freezing at specific temperatures halts cellular metabolic pathways and preserves cells and tissues for extended periods, prior freezing was tested as an alternative storage method for these samples. Two aliquots of nasopharyngeal swab samples were collected from 30 patients confirmed positive for COVID-19. The first aliquots were processed upon arrival at the local laboratory (in accordance with routine procedures), while the remaining aliquots were subjected to prior freezing (~-18 °C) for 30 minutes.

Step 2 (Sample Shelf Life Evalutaion): Due to the high turnover of nasopharyngeal swab samples during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Local Laboratory lacked the physical infrastructure for prolonged storage. As a result, after the test results were released, the samples were discarded and incinerated. Based on the premise that other high-complexity laboratories routinely store samples for extended periods, we evaluated the shelf life of samples from 15 patients confirmed positive for COVID-19 over a period of seven days. Four aliquots were taken from each sample: the first aliquot was processed 30 minutes after prior freezing (~-18°C) for 30 minutes on day 0 (D0), the second aliquot was processed on day 3 (D3), the third on day 5 (D5), and the fourth on day 7 (D7).

Comparison Test

Step 3 (Virus inactivation procedure): At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the primary challenge to implementing largescale RT-PCR testing in laboratory routines was the difficulty in identifying an RNA extraction process that was efficient, low-cost, fast, and biosafety compliant. Based on this challenge, in experiment No. 3, the SARS-CoV-2 RNA extraction process was replaced with a virus inactivation protocol involving heating to 95 °C for 15 minutes in a Dry Water Bath NT 362 – Dry Blo. Two aliquots of nasopharyngeal swab samples were taken from 300 patients presenting clinical symptoms of COVID-19 but without a confirmed diagnosis. The first aliquot was frozen for 30 minutes upon arrival at the Local Laboratory. After freezing, 25 μL of “Proteinase K” (20 mg/mL, Invitrogen™) was added and vortexed. The aliquot was then heated to 95°C for 15 minutes in the dry water bath. The second aliquot was similarly frozen (~-18 °C) for 30 minutes upon arrival, but RNA extraction was conducted using the standard method routinely applied at the laboratory.

Inactivation Improvement

Step 4 (Assessing the Optimal Amount of Proteinase K): After validating the inactivation process, in experiment No. 4, we determined the optimal volume of Proteinase K to add to the samples. This approach aims to minimize costs and prevent unnecessary enzyme waste. Four aliquots of nasopharyngeal swab samples were collected from 15 patients confirmed positive for COVID-19. All aliquots were frozen (~-18 °C) for 30 minutes upon arrival at the Local Laboratory. In the first aliquot, 25 μL of Proteinase K was added; in the second, 15 μL; in the third, 10 μL; and in the fourth, 5 μL. After enzyme addition, all aliquots were subjected to 95 °C for 15 minutes in a Dry Water Bath NT 362 – DryBlo.

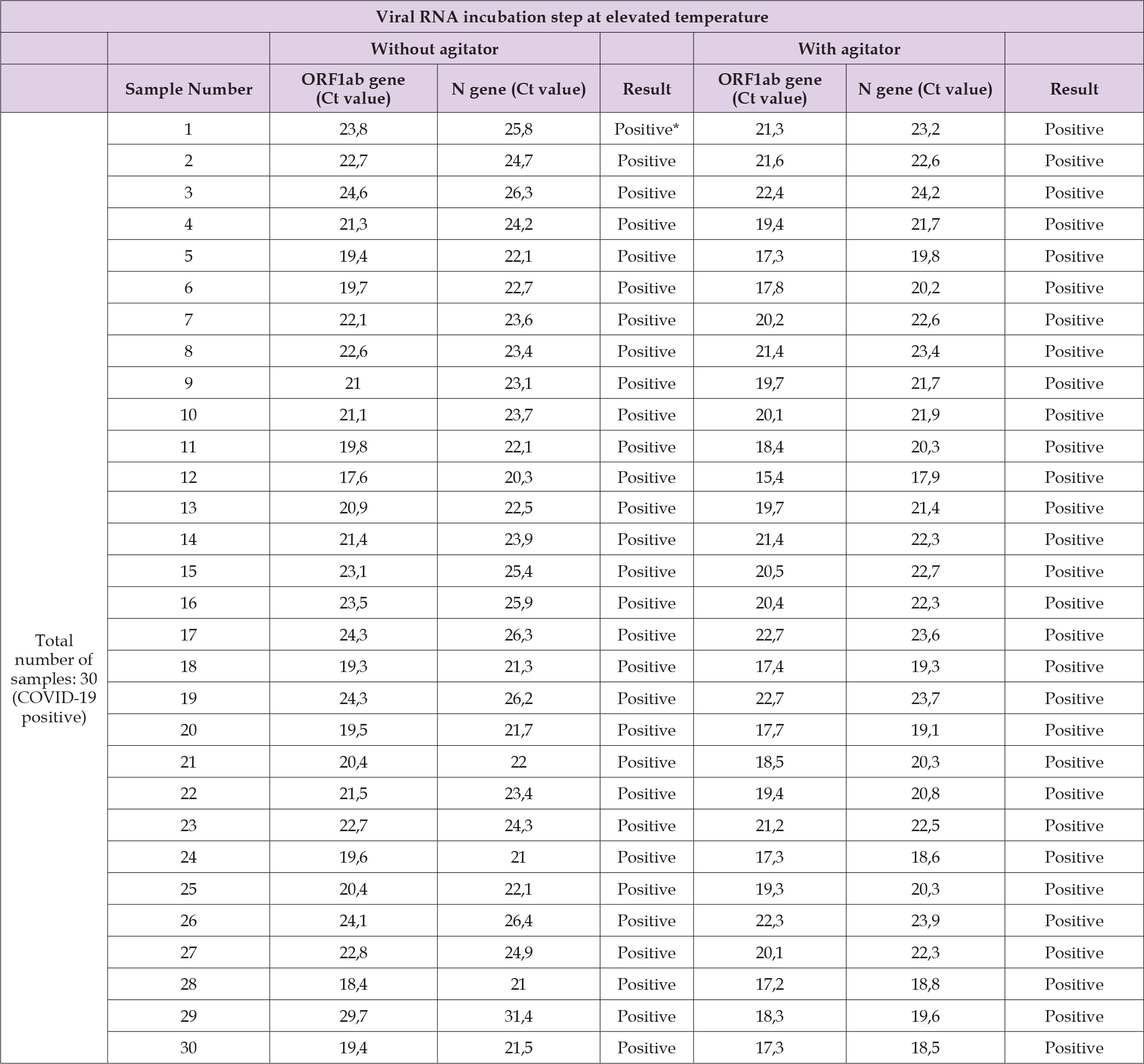

Step 5 (Evaluation of Samples Shaking Effects): In this final experiment, we chose to test the use of a thermoblock with a shaker (MTC-100 Thermo Shaker Incubator - Hangzhou Mil Instruments Co. Ltda) to determine whether shaking the samples during the 15 minutes at 95 °C helps achieve better homogenization of the samples in the inactivation process. Two aliquots of nasopharyngeal swabs were collected from 30 patients confirmed positive for COVID-19. These aliquots were frozen (~-18 °C) for 30 minutes upon arrival at the Local Laboratory, and 25 μL of Proteinase K was added. One aliquot was subjected to 95 °C for 15 minutes in a Dry Water Bath NT 362 – Dry Blo, while the other aliquot was subjected to 95 °C for 15 minutes in a thermoblock with shaker (MTC- 100 Thermo Shaker Incubator - Hangzhou Mil Instruments Co. Ltda).

Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 using Real-Time PCR

For the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2, all samples included in the study used the “VIASURE SARS-CoV-2 Real-Time PCR Detection Kit” with Ref. VS- NCO236 and VS-NCO272, following the guidelines in the manufacturer’s manual (CerTest Biotec). The ORF1ab region of SARSCoV- 2 plays a crucial role in COVID-19 diagnosis using the RT-qPCR technique, as it is one of the main target regions for virus detection. ORF1ab is a viral genome sequence that encodes non-structural proteins essential for viral replication and infection, such as RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and viral protease. These proteins are vital for viral replication, making the ORF1ab region a reliable target for detecting SARS-CoV-2 in the body. Thus, the cycle threshold (Ct) value of the ORF1ab gene was used to determine the detection result, with a Ct value greater than or equal to 30 defined as negative, and below 30 as positive. The Ct value of the N gene was analyzed following the initial analysis of the ORF1ab gene. The Qiagen/Corbett Rotor-Gene® instruments, along with accessories compatible with Real-Time PCR, were used. The analysis of Real-Time PCR data generated by the Rotor-Gene thermocycler was performed using the “Q-Rex” software, developed by QIAGEN.

The results were categorized and presented according to the respective tests.

Step 1

A sample from 30 patients known to be positive for COVID-19 was processed immediately upon arrival at the Local Laboratory at room temperature. All these samples showed a delay in the amplification of the ORF1ab and N genes compared to the amplification results of the same genes from samples that had been previously frozen (~-18 ºC) for 30 minutes (Figure 2) (Supplementary Table 1). For the ORF1ab gene, the average Ct values were 25.0 and 23.0, with standard deviations (SD) of 2.51 and 2.41 cycles, respectively (p-value = 0.0008917). For the N gene, the average Ct values were 26.4 and 24.8, with SD values of 2.17 and 2.49 cycles, respectively (p-value = 0.002944) (Table 1).

Table 1: Comparative reverse transcription real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) results were obtained by comparing two preconditioning temperatures (“room temperature” and “frozen”) for a total of 30 nasopharyngeal swab samples from COVID-19-positive patients. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of cycle threshold (Ct) values for the ORF1ab and N genes of SARS-CoV-2, along with the p-value comparing the average results obtained.

Supplementary Table 1: Cycle threshold (Ct) results for the amplification of the ORF1ab and N genes of the SARS-CoV-2 virus from all 30 (thirty) nasopharyngeal secretion samples of COVID-19 positive patients, comparing the results of two previous conditions of these samples (at room temperature and frozen) – Continued.

Note: “Positive*” = positive for COVID-19.

Step 2

Four aliquots were taken from 15 patients known to be positive for COVID-19. Each aliquot was previously frozen (~-18 ºC) and processed at different time points (1st day, 3rd day, 5th day, and 7th day). An increase in the delay in amplification of the ORF1ab and N genes was observed as the days progressed (Figure 3) (Supplementary Table 2). For the ORF1ab gene, the average Ct values were 21.00, 23.66, 31.49, and Not Detected, with SD values of 2.74, 2.87, 0.95, and invalid cycles, respectively. When comparing the 1st and 3rd days, the result was statistically significant with a p-value of 0.0003615, and when comparing the 3rd and 5th days, the p-value was 0.03052. For the N gene, the average Ct values were 22.73, 24.99, 33.23, and Not Detected, with SD values of 2.63, 2.56, 1.23, and invalid cycles, respectively. When comparing the 1st and 3rd days, the result was statistically significant with a p-value of 0.0003606, and when comparing the 3rd and 5th days, the p-value was 0.03052 (Table 2).

Supplementary Table 2: The cycle threshold (Ct) results for the amplification of the ORF1ab and N genes of the SARS-CoV-2 virus were analyzed in a total of 15 (fifteen) nasopharyngeal secretion samples from COVID-19 positive patients, comparing the shelf life (“D0,” “D3,” “D5,” and “D7”) of these samples.

Note: “Positive*” = positive for COVID-19; “Negative**” = negative for COVID-19; “Not detected***” = viral material not detected and “No result****” = no defined result.

Table 2: Comparative reverse transcription real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) results were obtained by comparing the shelf life (“D0”, “D3”, “D5”, and “D7”) of a total of 15 nasopharyngeal swab samples from patients known to be positive for COVID-19. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of cycle threshold (Ct) values for the ORF1ab and N genes of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), along with the p-value for the comparison of the average results obtained.

Step 3

Both aliquots from 300 patients with clinical suspicion of COVID-19 but without a definitive diagnosis were previously frozen (~-18 ºC) for 30 minutes. The RNA extraction process for the SARSCoV- 2 virus was performed on one aliquot, while the virus inactivation process was conducted on the other (Figure 4) (Supplementary Table 3). Of these samples, 2 (nos. 46 and 127) were excluded due to discrepancies in the results, requiring retesting for comfirmation (Supplementary Table 04). Of the remaining 298 samples, 210 tested positives for COVID-19, while 88 tested negatives. In all samples where RNA was extracted from the SARS-CoV-2 virus using the gold standard method, a delay in the amplification of the ORF1ab and N genes was observed compared to inactivation. ORF1ab gene: The average Ct values were 21.79 and 19.98, with standard deviations (SD) of 3.28 and 3.24 cycles, respectively (p-value = 2.2e-16). N gene: The average Ct values were 23.75 and 22.11, with SDs of 3.18 and 3.19 cycles, respectively (p-value = 2.2e-16) (Table 3).

Table 3: Comparative reverse transcription real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) results were obtained by comparing two processes for releasing the genetic material of the COVID-19 virus (“Viral extraction” and “Viral inactivation”) from a total of 300 nasopharyngeal swab samples from patients without a definitive COVID-19 diagnosis. The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of cycle threshold (Ct) values for the ORF1ab and N genes of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), along with the p-value for the comparison of the average results obtained.

Supplementary Table 3: The cycle threshold (Ct) results for the amplification of the ORF1ab and N genes of the SARS-CoV-2 virus were analyzed in a total of 300 (three hundred) nasopharyngeal swab samples from patients without a definitive COVID-19 diagnosis, comparing two processes for releasing the genetic material of the COVID-19 virus (“Viral extraction” and “Viral inactivation”) – Continued.

Note: “Positive*” = positive for COVID-19; “Negative**” = negative for COVID-19 and “Not detected***” = viral material not detected.

Supplementary Table 4: The cycle threshold (Ct) results for the amplification of the ORF1ab and N genes of the SARS-CoV-2 virus from the re-test of 02 (two) nasopharyngeal swab samples (number 46 and 127) from patients with discrepancies in results when comparing the two processes for releasing the genetic material of the COVID-19 virus (“Viral extraction” and “Viral inactivation”). The re-test was conducted using the QIAGEN kit (“QIA amp Viral RNA Mini Kit”).

Note: Legend: “Positive*” = positive for COVID-19.

Step 4

Four aliquots were taken from 15 patients known to be positive for COVID-19, with each aliquot being previously frozen (~-18 ºC) before undergoing the SARS-CoV-2 virus inactivation process. The difference between these aliquots was the volume of “Proteinase K” added: 25 μL to the 1st aliquot, 15 μL to the 2nd, 10 μL to the 3rd, and 5 μL to the 4th (Figure 5) (Supplementary Table 5). An increase in the amplification delay of the ORF1ab and N genes was observed as the enzyme volume decreased. For the ORF1ab gene, the average Ct values were 19.91, 26.80, 33.79, and Not Detected, with standard deviation (SD) values of 1.93, 2.30, 2.13, and invalid cycles, respectively. Comparing the addition of 25 μL to 15 μL yielded a statistically significant p-value of 0.0007, while comparing 15 μL to 10 μL resulted in a p-value of 3.052e-05. For the N gene, the average Ct values were 21.47, 34.14, 37.21, and Not Detected, with SD values of 1.88, 2.09, 2.97, and invalid cycles, respectively. Comparing the addition of 25 μL to 15 μL yielded a p-value of 3.052e-05, and comparing 15 μL to 10 μL resulted in a p-value of 0.004181 (Table 4).

Supplementary Table 5: The cycle threshold (Ct) results for the amplification of the ORF1ab and N genes of the SARS-CoV-2 virus were analyzed in a total of 15 (fifteen) nasopharyngeal swab samples from patients known to be positive for COVID-19, comparing the amounts of proteinase K added to the reaction—25 μL, 15 μL, 10 μL, and 5 μL.

Note: “Positive*” = positive for COVID-19; “Negative**” = negative for COVID-19; “Not detected***” = viral material not detected and “No result****” = no defined result.

Table 4: Comparative reverse transcription real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) results were analyzed to compare the amounts of proteinase K added to the reaction in μL (“25 μL,” “15 μL,” “10 μL,” and “5 μL”) across a total of 15 nasopharyngeal swab samples from patients known to be positive for COVID-19. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of cycle threshold (Ct) values for the ORF1ab and N genes of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), along with the p-values comparing the average results obtained.

Step 5

Two aliquots were taken from 30 patients known to be positive for COVID-19, with each aliquot previously frozen (~-18 ºC) before undergoing the SARS-CoV-2 virus inactivation process. The difference between these aliquots was in the equipment used: the first aliquot was processed using the Dry Water Bath NT 362 – DryBlo, while the second was processed with the thermoblock equipped with an agitator (MTC- 100 Thermo Shaker Incubator - Hangzhou Mil Instruments Co. Ltda) (Figure 6) (Supplementary Table 5). An earlier amplification of the ORF1ab and N genes was observed in the second aliquot. ORF1ab gene: The average Ct values were 21.70 and 19.61, with standard deviations (SD) of 2.43 and 1.93 cycles, respectively (p-value = 1.342e-06). N gene: The average Ct values were 23.77 and 21.32, with SD values of 2.32 and 1.82 cycles, respectively (p-value = 1.329e-06) (Table 5) (Supplementary Table 6).

Table 5: Comparative reverse transcription real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) results comparing viral RNA incubation steps at elevated temperatures (“Without agitator” and “With agitator”) from a total of 30 nasopharyngeal swab samples of patients known to be positive for COVID-19. The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of cycle threshold (Ct) values for the ORF1ab and N genes of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), along with the p-value from the comparison of the average results.

Supplementary Table 6: The cycle threshold (Ct) results for the amplification of the ORF1ab and N genes of the SARS-CoV-2 virus were analyzed in a total of 30 (thirty) nasopharyngeal swab samples from patients known to be positive for COVID-19, comparing the viral RNA incubation step at elevated temperature (“Without agitator” and “With agitator”).

Note: “Positive*” = positive for COVID-19.

Statistical Analyses

The Ct values obtained in real-time RT-PCR reactions performed in all tests were compared by tests and p values < 0.05 were considered significant differences [48-53].

COVID-19

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an increased demand for RT-PCR testing, making it crucial to develop rapid and effective methods for the extraction and inactivation of SARS-CoV- 2 genetic material. These advancements aimed to facilitate analysis and reduce processing time. This surge presented significant challenges, particularly regarding response times for results and the extraction of viral genetic material [54]. As the pandemic intensified, many laboratories found themselves overwhelmed by the volume of testing requests. This situation was exacerbated by shortages in resources, personnel, and expertise, which hindered the efficient processing of samples. Although RT-PCR tests are highly accurate, they are time-consuming due to the complexity of extraction and amplification processes. Additionally, the lack of standardized procedures for sample handling and test execution contributed to variability in result quality and processing speed [55-58]. A critical issue was the RNA extraction from patient samples, a prerequisite for RT-PCR testing [54]. RNA extraction is a complex process requiring specialized equipment and trained personnel. Many laboratories faced difficulties due to the limited supply of commercial RNA extraction kits, which were in high global demand. Some research groups developed alternative protocols, while others turned to automated systems to alleviate this pressure, although these systems also required significant training and adaptation [59]. Among these research groups, we developed an alternative protocol for SARS-CoV-2 RNA extraction based on scientific evidence. This protocol demonstrated significant benefits by utilizing the prior freezing of nasopharyngeal samples containing SARS-CoV-2, combined with the use of proteinase K, elevated temperature, and agitation. This approach has been proven efficient and validated to facilitate viral RNA extraction and optimize virus detection by RT-PCR [60,61].

Prior Freezing of Nasopharyngeal Samples

The prior freezing of nasopharyngeal samples has proven to be a widely adopted practice for preserving RNA integrity and improving its extraction efficiency, particularly in RT-PCR tests for detecting SARS-CoV-2. This approach is crucial to ensuring the quality of molecular analyses, especially in scenarios where samples need to be transported or stored before processing. Studies indicate that freezing at low temperatures, such as -18 °C, -80 °C, or even lower, helps preserve the integrity of viral RNA by protecting it from enzymatic degradation, such as the action of RNases. Gao, et al. (2020) observed that prior freezing significantly contributes to the recovery of high-quality RNA, resulting in more efficient amplification during RT-PCR, even after prolonged storage periods [60]. Tariq, et al. (2020) supported these findings, demonstrating that freezing nasopharyngeal samples before RNA extraction reduces genetic material degradation and improves the quantity of RNA recovered [61]. This occurs because freezing facilitates cell rupture and the release of viral RNA without compromising the integrity of its genomic sequence. Additionally, freezing offers logistical advantages, allowing for the preservation of samples over extended periods and ensuring their stability during transportation to laboratories. Scheller, et al. (2020) highlighted that frozen samples exhibit greater stability for RNA extraction compared to fresh samples, which are more susceptible to enzymatic degradation [62,63].

Similarly, Dimeski (2020) reported that freezing is particularly advantageous for samples collected in remote locations, facilitating transport without compromising RNA quality [64,65]. The practice of freezing not only ensures the integrity of viral RNA but also improves the reliability and consistency of laboratory results. Moreover, it is essential in high-demand situations or adverse conditions, such as prolonged transportation needs, where the risk of degradation is elevated. Thus, this technique is recommended as an additional step to optimize the quality of molecular analyses and ensure the accuracy of diagnostic tests.

Elevation of the Temperature of Nasopharyngeal Samples

Raising the temperature has proven to be a crucial strategy for optimizing viral RNA extraction by facilitating the disruption of cell membranes and denaturing proteins that might interfere with the process. Studies show that heating samples, particularly to temperatures of 95 °C, effectively induces cell lysis and releases viral RNA, thereby improving the sensitivity and efficiency of diagnostic methods such as RT-PCR [25,66]. Duan, et al. (2020) demonstrated that applying heat during extraction significantly enhanced the efficiency of viral RNA release while also reducing the time required for sample preparation, resulting in greater sensitivity in molecular tests [67]. Additionally, the elevation of temperature, when combined with physical methods such as agitation, plays an essential role in breaking cell membranes, making viral RNA more accessible for subsequent analyses. This process is fundamental to the effectiveness of molecular diagnostics, especially in nasopharyngeal samples, which have a complex matrix of cells, mucosal components, and proteins. The combination of heating with the use of lytic agents, such as detergents or proteinase K, further enhances the release of viral RNA. Kozak, et al. (2020) highlighted that increasing the temperature during extraction promotes more efficient viral RNA release by breaking down cellular and viral protein structures, particularly in nasopharyngeal samples. This approach is widely supported by studies emphasizing the importance of efficient lysis for detecting viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 [68].

Addition of Proteinase K

Proteinase K played a fundamental role in enhancing laboratory protocols during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 and the extraction of viral RNA. This proteolytic enzyme, renowned for its robustness and efficiency under high-temperature conditions, has proven to be an indispensable tool for preserving RNA integrity in molecular analyses such as RT-PCR, which is essential for rapid and reliable virus diagnosis. Studies highlight that proteinase K maintains its activity at elevated temperatures, ranging from 56 °C to 95 °C, enabling efficient degradation of viral proteins and inactivation of the virus. This ensures the safety of professionals and the quality of the extracted RNA. Wu, et al. (2020) demonstrated that this approach results in high-quality viral RNA that is compatible with subsequent analyses, increasing efficiency in high- demand scenarios [69,70]. Haugen, et al. (2007) emphasized the stability of this enzyme at high temperatures, facilitating the efficient degradation of proteins and the release of viral RNA in clinical samples [71].

Additionally, Liu, et al. (2019) confirmed that applying proteinase K at 95 °C eliminates contaminating proteins, such as RNases, thereby improving the quality of the extracted RNA without compromising its integrity [72]. The versatility of proteinase K also extends to its application across various types of clinical samples. Verstrepen, et al. (2020) demonstrated that its use in saliva samples ensured safe virus inactivation and efficient RNA extraction [73]. Meanwhile, Zong, et al. (2020) reinforced its efficacy in nasopharyngeal samples, even under high-demand conditions such as pandemic peaks [74,75]. Moreover, combining proteinase K with heating and agitation has proven advantageous in accelerating RNA extraction and reducing the time required for molecular testing. Martins, et al. (2021) reported that this combination of heating and enzyme increased the amount of RNA extracted, while Gao, et al. (2020) highlighted that heating samples accelerates cell lysis and minimizes the impact of interfering proteins [76,77].

Use of a Shaker

Mechanical agitation during viral RNA extraction has proven to be an efficient technique for homogenizing samples and physically disrupting cells, promoting more effective RNA release. This step is essential for enhancing the sensitivity and accuracy of RT-PCR tests, ensuring reliable and consistent results. Martins et al. (2021) demonstrated that using mechanical shakers during viral RNA extraction significantly improved cell disruption, enabling more efficient sample homogenization and more precise amplification in RT-PCR [78]. Agitation accelerates RNA release by increasing the interaction between the lysis reagent and the cells or viruses present, particularly in samples with high viscosity or protein content. Zhao, et al. (2020) supported these findings, showing that the use of shakers in nasopharyngeal samples resulted in a more uniform extracted solution, which enhanced the sensitivity and accuracy of the detection process [79]. Additionally, Chen, et al. (2018) observed that mechanical agitation during extraction improved both the quantity and quality of RNA extracted from clinical samples, contributing to more precise diagnoses [80]. The efficiency of this method is also reflected in the reproducibility of results. Jiang et al. (2021) indicated that the use of shakers reduces variability among samples, ensuring consistent RNA concentrations, even when analyzing large volumes of heterogeneous samples [81]. Moreover, the proper exposure of viral RNA following cell membrane disruption, facilitated by agitation, is crucial for the sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2. Liu et al. (2020) observed that efficient RNA exposure in nasopharyngeal samples improved amplification during RT-PCR, increasing the test’s sensitivity [82].

The combination of prior freezing of nasopharyngeal samples, the use of proteinase K, elevated temperatures, and mechanical agitation constitutes a highly efficient and validated approach to optimizing viral RNA extraction and SARS-CoV-2 detection via RT-PCR. Freezing preserves RNA integrity by minimizing enzymatic degradation and ensures sample stability during transport and storage. Proteinase K provides a practical and reliable solution by accelerating cell lysis and protein degradation, particularly at elevated temperatures, such as 95 °C, owing to its thermostable robustness. Heating and agitation further enhance cell membrane disruption, maximizing viral RNA release and improving the sensitivity and accuracy of molecular diagnostics. These practices not only ensure high- quality RNA extraction but also reduce processing time, a critical factor in high-demand scenarios like the COVID-19 pandemic. This integrated approach delivers safe, rapid, and scalable analysis, effectively meeting the demands of processing large sample volumes efficiently and cost-effectively. Backed by robust scientific evidence, this strategy is indispensable for ensuring timely and reliable diagnoses, significantly contributing to the effective management of public health emergencies. Incorporating agitators into RNA extraction protocols ensures uniform and effective extraction while enhancing the sensitivity and precision of molecular diagnostics, establishing itself as an essential practice in laboratories.

Similarly, the use of elevated temperatures, either alone or combined with lytic agents, is widely recommended to optimize viral RNA extraction, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of molecular diagnostic results. Thus, this combination of methods represents a practical, efficient, and validated solution for large-scale molecular diagnostic demands, reaffirming its crucial role in high-pressure laboratory contexts during public health emergencies.

The authors would like to thank Cremasco Medicina Diagnóstica for the assistance provided and for making the facility available for the development and execution of the project. This study benefited from valuable contributions from all team members at this laboratory, as well as assistance from the Pró-reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação at the UFES.

This study was supported by the company Nova Biotecnologia, which provided essential supplies (kits, reagents, and other materials) for the laboratory tests, as well as by Cremasco Medicina Diagnóstica and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Espírito Santo - FAPES

The Research Ethics Committee of the Health Sciences Center at UFES approved this study (Study Protocol: 39187320.4.0000.5060). No human subjects were included in this study. The SARS-CoV-2 genetic material was isolated from nasopharyngeal samples of patients with suspected COVID-19 and was not linked to the donors.

M. Palaci formulated and planned the study, facilitated the provision of facilities and necessary supplies, and provided guidance on modifications to the experiments. F.A.F. Martins and J.M. da Silva assisted with the experimental procedures, helping with the practical aspects and bench development. A. Rodrigues handled all the statistical aspects of the project, facilitating and enabling the development of the conclusion and discussion of the results. The final manuscript was reviewed and approved by all authors.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.