Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Ali NF1* and Abdel-Salam IS2

Received: January 16, 2025; Published: January 21, 2025

*Corresponding author: Ali NF, Dyeing and printing department, National Research Centre, 12421-Dokki, Cairo, Egypt

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2025.60.009429

Propolis is known to possess a variety of antibacterial actions and antifungal, including those that prevent cell division, collapse microbial cytoplasmic cell membranes and cell walls, limit bacterial motility, inactivate enzymes, cause bacteriolysis, and prevent protein synthesis. Pathogenic bacterial isolates, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, together with a pathogenic fungal isolate, Aspergillus Niger, were tested. The antimicrobial efficacy of wool fibers dyed with curcumin pretreated with propolis and natural dye were assesed. Wool fibers were dyed with a natural color that was derived from curcumin by microwave and ultrasonic. Wool fibers were treated with propolis prior to being dyed. The investigation focused on the dye concentration, pH variables, color strength, color data, and fastness properties of the dyed wool fibers. The outcomes showed that propolis-treated wood fibers performed better than untreated wool fibers. Propolis exhibits antibacterial activity against certain microorganisms. The outcomes showed that propolis therapy improved the antimicrobial activity, by using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the morphologies and structures of the wool fibers that were both pretreated and untreated were analyzed. The results obtained showed that the surface of the untreated wool fibers is rough. In comparison to the untreated wool fibers, the pretreated wool fibers were swollen.

Keywords: Propolis; Antimicrobial; Application; Textile

Pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria and fungi are typically found on human skin, in nasal cavities, and other locations like the genital area. Microorganisms can enter a textile material directly through clothing or through other textiles in the vicinity. It is among the most likely reasons why hospital infections occur. According to recent research, germs may enter the air through contaminated fabrics and then spread across the surrounding area. Textiles have been reported to harbor pathogenic bacteria such as Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus epidermidis [1] Furthermore, microorganisms have the ability to produce unpleasant odors, stains, and harm to the mechanical qualities of fibers, all of which can reduce the effectiveness of a textile industry product. It might encourage skin pollution, inflammation, and atopic dermatitis in susceptible individuals. When used in close proximity to patients or in the environment, antimicrobial textiles can greatly lower the risk of infection [2]. Natural or artificial substances that prevent the growth of microorganisms are known as antimicrobial agents. These are inhibitors of protein, lipid synthesis, or enzymes, all of which are necessary for cell life; alternatively, they can destroy the microorganisms by breaking down their cell walls. Biocides make up the majority of synthetic antibacterial agents used on textiles. Numerous products, including sportswear, outdoor clothing, undergarments, shoes, furniture, hospital linens, wound care wraps, towels, and wipes, can be made using antimicrobial textiles.

A variety of testing techniques have been created to evaluate the effectiveness of antimicrobial textiles. like the agar diffusion test (qualitative approach similar to the halo method) and the dynamic shake test (quantitative method like the serial dilution and plate count method) [3]. Bees use a variety of plant materials, including leaves, flowers, and bud exudates, to generate propolis, also known as bee glue. Propolis is transformed by bee secretions and wax [4,5]. Numerous research teams have shown that propolis of various kinds has antimicrobial qualities. found that poplar propolis possesses antibacterial properties against a variety of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including multidrug-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus that are resistant to the antibiotic methicillin (MRSA) [6]. The preparation of wool fibers with propolis to improve coloring and antibacterial activities is the goal of this work. Preventing cross-infection by harmful bacteria is crucial. These therapies manage the microbial invasion. Additionally, they stop bacteria’ metabolism to prevent odor from forming, staining, discoloration, and loss of quality in the fiber products [7-9]. On the other hand, the purpose of this study is to employ a natural dye made from curcumin. In order to save the environment and stop industrial pollution, natural dyes have been utilized to color fibers. Economical techniques including microwave heating and ultrasonic energy were used to carry out dyeing. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of wool fiber pretreated with Propolis before dyeing process with curcumin as natural dye.

Materials

• Wool Fibres (10/2) • Propolis and Curcumin

Devices:

• Ultrasonic: A 5.75-liter, 38.5-kHz-frequency, thermostatic CREST tabletop 575 HT ultrasonic cleaner with a maximum output of 500 Watts was utilized. There are 500 Watts to 100 Watts of output power available.

• Microwave: The Samsung M 245 microwave, which had a 1,550-watt output and operated at 2450 MHz, was the apparatus utilized in this experiment.

Propolis Extraction

Propolis was extracted using a variety of solvents, including ethanol, water, methanol, ethyl acetate, and others. For the majority of them, ethanol extracts have the highest activity. Maceration and Soxhlet extraction with ethanol are simple methods for obtaining propolis extraction.

Pre-Treatment of Wool Fibers with Propolis

Wool fibres were pad-dried-cured. The wool fibres were treated with liquid propolis (2–10%), padded to 100% wet pick up, dried for 5 minutes at 80 ºC, and then cured for 3 minutes at 120 ºC.10 SEM, or scanning electron microscopy: Investigating the surface morphology of both treated and untreated wool fibres was done using a JSMT-20 scanning electron microscope (JEOL-Japan). Prior to inspection, the surface of the wool fibres was prepared on a suitable disc and sprayed randomly with gold. SEM work was done at Egypt’s National Research Centre.

Dyeing Procedures

Microwave Dyeing of Wool Fibres: Wool fibres were microwave- -heated at varying pH values (3-9) for varying periods (1-5 minutes) in a dye bath with varying quantities of dye and a liquor ratio of 30:1. Following a 30-minute soak in a 60:1 liquor ratio and 3 g/L non-ionic detergent (Hosta pal CV, Clariant), the dyed samples were rinsed with cold water, dried at room temperature and then rinsed again. Dyeing, Wool Fibres Using an Ultrasonic Technique: Wool fibres were coloured at pH 5 and L.R. 1:50 using 2g of curcumin rushing ultrasonic dye. The samples were immersed in a bath containing 5g/l non-ionic detergent and dyed for 30 minutes at 500C using an ultrasonic power of 500watts. After the dyeing process, the samples were rinsed with cold water. dried at room temperature.

Measurements of Colorimetric Data

All colored fabrics’ color coordinates and color strength (K/S) were specified using the CIELAB color space system (commonly represented as L*, a*, and b* coordinates). Using a Hunter Lab Ultra Scan PRO spectrophotometer (USA) with an illuminant D65, 10 standard observers, the following parameters were also measured: b* indicates yellowness if positive or blueness if negative; c* specifies chroma; h indicates hue angle; and L* indicates lightness or darkness of the sample (a higher lightness value represents a lower color yield). It was calculated to find the total color difference values (ΔE).

Assessments of the Antimicrobial

Utilising conventional techniques (serial dilution and plate count method), the antimicrobial properties of wool fibres pre-treated with propolis and coloured with natural curcumin colours were assessed. The blanks for the serial dilution were made in bottles with 99 millilitres of distilled water, labelled in a sequential manner from 10−1 to 10−5, and then autoclave sterilised. Each fibre sample was added in 1.0 gm increments to a solution of 99 ml, millilitres of distilled water, labelled in a sequential manner from 10−1 to 10−5, and then autoclave sterilised. Each fibre sample was added in 1.0 gm increments to a solution of 99 ml, or a 10−1 dilution. Using a new, sterile pipette, 1 ml of this was then transferred to 9 ml of the test tube labelled 10−2, or the 10−2 dilution; this process was repeated for each subsequent level until 10−5. Peptides that are nutrients Bacterial strains were counted using agar media.

ResultsImpact of Various Propolis Concentrations

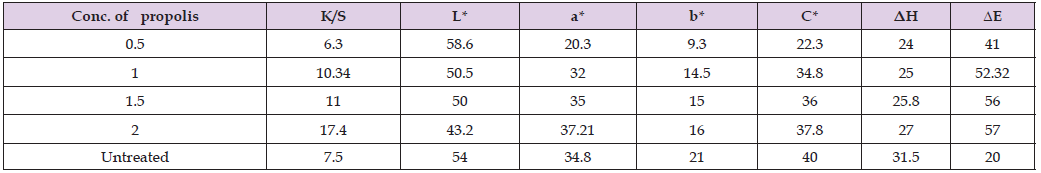

We assessed the effects of various propolis concentrations (0.5,1,1.5, 2 and 2.5ppm) on wool fibers that had been pretreated with propolis and dyed with curcumin natural dye. The outcomes demonstrated that, when wool fibres were dyed with curcumin dyes and pretreated with propolis, the 2-ppm concentration of propolis produced the highest value of K/S. This was assessed using the ultrasonic method, as presented in Table 1.

Colour Data of Wool Fibres Pre-treated with Propolis at Varying Concentrations and Dyed with Curcumin

The colorimetric data (L*, a*, and b*, C*, ΔH, ΔE) of several fibres dyed with varying microwave-extracted dye concentrations are displayed in Table 1. We may infer from the data in the table that when the extracted dye concentration increased, L* values decreased as well, making the samples’ colour darker. The values of a* and b* grew positively as the dye concentration rose. The colour of the dyed wool fibres darkened and became more reddish yellow as the dye concentration increased from 0.5 to 2 ppm. The identical outcomes of the ultrasonic technique, as displayed in Table 2.

Table 2: Color data of dyed wool fibers with curcumin /propolis at various concentrations. with ultrasonic method.

Effect of Ph on Dyed Wool Fibers that have been Pretreated with Propolis on the Intensity of Color

The dye bath pH had an impact on the color strength of wool fibers colored with the natural dye under investigation. According to Figure 1, the dye used to dye the wool fibers produced the highest color strength (K/S) value at pH 5 for the ultrasonic method and pH 4 for the microwave technique.

Effect of Time of Microwave-Dyed Fibers, Both Treated and Untreated

Figure 2 illustrates the impact of dyeing time on propolis-treated wool fibers that were then microwave-dyed with curcumin. The color strength reached its maximum values after five minutes, according to the data.

Antimicrobial Activity

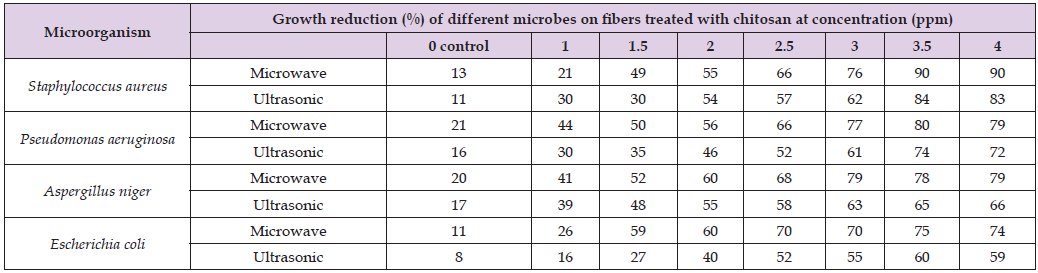

Pathogenic bacterial isolates, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, together with one pathogenic fungal isolate, Aspergillus niger, were utilized to assess the antibacterial efficacy of wool fibers dyed with curcumin and pretreated with propolis [10]. It is evident from the results in the tables that the concentration of propolis affects the antibacterial activity of wool fibers. The antimicrobial activity of different strains of bacteria and fungi varies, and as the concentration of propolis increases, so does the rate of bacterial decrease. The type of bacteria and fungi determines how much these increase [11,12]. Numerous researchers have documented the antibacterial action of certain natural colors when combined with propolis treatment against pathogenic bacteria and fungus. The prepared sample fabrics exhibit higher antibacterial activity against Gram-positive (S aureus) bacteria than against Gram-negative (E coli) bacteria. The outcomes demonstrate that treated fibers have more antibacterial activity than untreated fibers. The antibacterial activity of wool colored using the microwave and ultrasonic methods differs slightly [13]. The antimicrobial properties of wool fibers treated with natural dye and propolis were found to be more efficient against pathogenic fungus like Aspergillus niger and Staphylococcus aureus G+ than Escherichia coli G- [14-21] (Table 3 & Figure 3).

Table 3: Antimicrobial activity of dyed wool fibers pre-treated with different concentrations of propolis and dyed by microwave and ultrasonic methods.

Note: Control: untreated wool.

Surface Morphology

By using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the morphologies and structures of the wool fibers that were both pretreated and untreated were analyzed. Using a scanning electron microscope (SEM), Figure 4 shows the SEM images of the untreated wool fibers and Figure 5 shows the treated fibers. This shows the effect of treating wool fibers with 4g/Lconic. propolis. As can be seen in (Figures 4 & 5), the untreated samples have a rough surface. In contrast, the treated samples have smooth and even surfaces, increased fiber diameter, and were swollen in comparison to the untreated fibers. The modifications in the surface morphology brought about by the treatment’s active substances

Ionic conduction, a form of resistive heating, is the method by which the microwave heating operates. The dye molecules collide with the fiber molecules as a result of the ions’ acceleration through the dye solution.

In an acidic media, the dye has a strong affinity for the fibers. Through electrostatic attraction, actionized amino groups can adsorb anionic dye molecules in acidic media. Propolis has been shown to possess a variety of antibacterial properties, such as the ability to hinder cell division, collapse microbial cytoplasm cell membranes and cell walls, inhibit bacterial motility, inactivate enzymes, cause bacteriolysis, and inhibit protein synthesis [6,7]. Propolis’ polyphenols can interact with a variety of microbial proteins to generate ionic and hydrogen interactions, which can change a protein’s three-dimensional (3D) structure and, consequently, its activity [8,9]. This difference in antibacterial activity is likely attributed to the fact that Gram-positive bacteria have single-layered cell walls, while Gram-negative bacteria have multilayered cell walls enclosed by an outer membrane [13,22- 27].

Wool fibers are pretreated with propolis before being dyed with curcumin. It causes a significant absorption of dye. Because of the treatment, color strength (K/S) values showed high values. Measurements were made of the antimicrobial activity against specific species of bacteria and fungi, and the results show a significant reduction in percentage for the treated compared to the untreated fibers. The wool fibers’ color strength (K/S) and dye extraction showed that microwave heating is superior than ultrasonic heating. Using microwave is an effective way to save time and energy. In addition, it produces a higher dye uptake than ultrasonic procedures and is more environmentally friendly. Natural dyes require little equipment and small-scale processes, but they are non-polluting. It gave good natural dyeing qualities; it appears to be a good substitute agent for less harmful production processes in the textile industry.

The authors have no conflict of interest.