Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Wubshet listeria*

Received: November 18, 2024; Published: November 29, 2024

*Corresponding author: Wubshet listeria, Wollo zone animal resource development office, Dessie, Ethiopia

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.59.009339

Background: Listeria monocytogenes is a bacterium of veterinary and public health importance, worldwide. The

pathogen is among the major causes of abortion in dairy cattle. Listeriosis in humans is the main food-borne zoonotic

illness resulted from consuming dairy and other food products contaminated with mainly Listeria monocytogenes.

A cross-sectional study was conducted from November 2020 to May 2021 to isolate Listeria monocytogenes

from raw bovine milk samples, to determine the Antibiogram of isolates and to understand its public

health implication in smallholder dairy farms. Listeria species isolation was performed, according to standard

bacteriological procedures, using Buffered Listeria Enrichment broth (BLEB) and Polymyxin Acriflavine Lithium-

chloride Ceftazidime Aesculin Mannitol (PALCAM) agar and for confirmation and species identification:

carbohydrates utilization tests using xylose, mannitol and rhamnose sugars, hemolysis test using blood agar,

Christie Atkins Munch Peterson (CAMP) test and Listeriolysin 0 latex agglutination test was carried out. The

antimicrobial susceptibility test using 9 commonly used antimicrobial drugs against 15 Listeria monocytogenes

isolates, and a questionnaire survey were also conducted.

Results: From the total of 384 samples the overall prevalence of Listeria species was 12.8% (49/384) and specifically

for Listeria monocytogenes was 4% (15/384). In this study, listeriosis is significantly associated with

farm management systems and herd size (p-value< 0.05). Based on the antimicrobial susceptibility test, it was

found that Listeria monocytogenes was sensitive to most drugs except Sulfamethoxazole and nalidixic acid which

in both showed 100% resistance. 13.3% of L. monocytogenes isolates were also resistant to oxytetracycline,

tetracycline, procaine penicillin G and cloxacillin.

Conclusion: This presence of Listeria monocytogenes in raw milk and its multi-drug resistance pattern is an indication

of a serious public health risk. Therefore, creating awareness to the farmers, and dairy product consumers,

implementation of milk safety hygienic practices, implementation of countrywide surveillance and further

research to estimate its prevalence both in animals and humans is strongly recommended.

Keywords: Antibiotic Susceptibility; Dairy; Listeria Monocytogenes; South Wollo

Abbreviations: BLEB: Buffered Listeria Enrichment Broth; PALCAM: Polymyxin Acriflavine Lithium-Chloride Ceftazidime Aesculin Mannitol; CAMP: Christie Atkins Munch Peterson; DOA: District Office of Agriculture

Listeria species are ubiquitous and they have unique characteristics that permit growth at a freezing temperature which is usually not possible for most food-borne microorganisms (Rocourt, et al. [1]). Listeria can also resist a pH between 4 and 9.6 [1]. Among the species, L. monocytogene is an important cause of human and animal listeriosis. Listeriosis is the main food-borne zoonotic illness because 99% of human infections are resulted from eating food products contaminated with mainly L. monocytogenes [2]. It is a Gram-positive, rodshaped, motile, and non-spore-forming bacterium [3] and is primarily known as a veterinary pathogen, which causes basilar meningitis (circling disease) and abortion in sheep and cattle [4]. Outbreak and sporadic cases of human listeriosis have been associated with contamination of food items like milk, meat, and their products [5] Listeria could ingest with poorly fermented silage which is not acidic enough to kill the bacteria. It also has been ingested through the soil on the grass and placenta from the infected cow. This organism can also vertically transmit from mother to fetus via the placenta and through the infected birth canal [6,7]. In the USA L. monocytogenes infections are associated with a 94% infection rate and a 15.9% mortality rate [8] The mortality rate ranges from 30% to 75% mainly in high-risk groups such as pregnant women, unborn or newly born infants, elderly people, persons with disease conditions like HIV AIDS, and immunocompromised persons were recorded [6,7] Listeriosis is one of the important emerging bacterial zoonotic diseases worldwide [9].

Unlike infection with other common foodborne microorganisms, it is associated with the highest case of fatality rate [10]. However, for reasons related to lack of awareness of its incidence and lack of detection facilities and inadequate resources together with giving more priorities to other epidemics than listeriosis, its public health significance is not well understood in developing countries including Ethiopia [11]. Raw milk and milk product consumption are very common in Ethiopia, exposing the public to zoonotic infections including Listeria [12,13]. Few researchers had isolated L. monocytogene from raw milk and dairy products from the central highlands of Ethiopia [14,15] and regarding human listeriosis, only one study done in Tigray reported 8.5% of L. monocytogenes Prevalence (12/141) among pregnant women [16]. The majority of the studies in Ethiopia were conducted with microbiological culture assays by taking samples from retail shops in peri-urban and urban areas, therefore being represented only a small fraction of approximately 2% of milk produced in the country [17]. However, with the prevailing informal milk markets, poor hygiene practices and underdeveloped veterinary services, high infection and illness are expected to be prevalent in Ethiopia. The present study is therefore conducted to produce evidence for a better understanding of the epidemiology and public health risk of L. monocytogenes pertinent to smallholder dairy farms in the Kombolcha town and Kutaber district of South Wollo zone. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to isolate L. monocytogenes from raw bovine milk samples, to estimate the prevalence of L. monocytogenes in small-holder dairy farms, to investigate the susceptibility of isolates to commonly used antimicrobials and to determine public health implications of L. monocytogenes in dairy farmers and the surrounding community who consumes raw milk and other dairy products.

Study Area and Study Period

The study was conducted from November 2020 to May 2021 at Kombolcha town and Kutaber District of South Wollo zone, Amhara regional state of Ethiopia. Kombolcha town and Kutaber district are the major milk-producing areas in the South Wollo Zone. Kombolcha is located 380 km northeast of Addis Ababa. The town has 12 Kebeles with a total population of 143,637, of whom 71,103 were men and 72,534 women. Kombolcha is found at the latitude of 11.083° N and a longitude of 39.733°E with an elevation ranging from 1,842 and 1,915 meters above sea level. It has an annual rainfall ranging from 500 - 900 ml of which 84% is in the long rainy season (June to September) and the dry season extends from October to February. The annual temperature is ranging from 21°C to 36°C. According to the District Office of Agriculture (DOA) report, the district has a total area of 78.6 km2. About 33.6% of the area is under crop production, and 1.47% is serving as grazing land [18]. Based on the South Wollo zone animal resource development office data, the total cow population in Kombolcha is 9968, and the number of dairy farms that are holding from 3 up to 15 cows is 521.

According to the zone’s report, moderate and large-scale dairy farms in the Kombolcha town are reached 165 [19]. Kutaber is also located in the South Wollo zone. The district is found at 39.031o12” -39.034o12” E longitude and 11.012o36” -11.018o36” N latitude and poses highland and lowland areas. The average rainfall ranges from 500 to 955ml in the short and long rainy seasons. The area’s annual temperature is 22 °C on average [20]. The main job of the population of the wereda is mixed crop-livestock agriculture. The main livestock reared in the area are cattle, sheep, goats, and equine [21]. The district has one of the main milk suppliers for Dessie city. Similarly, according to the zone’s report, the district has a livestock population of 74,910 and a cow population of 29674, and the number of large-scale dairy farms is reported as 5 [19].

Study Design and Sampling

A cross-sectional study design was used to collect raw bovine milk samples from randomly selected smallholder dairy farms in Kombolcha town and Kutaber district and to undertake laboratory work from November 2020 to May 2021 with objectives of determining the prevalence of L. monocytogenes, antimicrobial susceptibility test of isolates and to understand its public health implications. Dairy farms holding from 3-15 cows were selected for this study. All twelve kebeles from Kombolcha town were included. On the other hand, eight kebeles out of twenty-two kebeles of the Kutaber district were selected based on the accessibility of roads and the number of dairy farms. Since there was no previous study in the area, according to Thrusfield [22], by taking 50% expected prevalence with 95% confidence interval and 5% absolute precision. The sample size was calculated as a total of 384 samples. According to Jorgensen 30 ml of raw milk [23] was collected aseptically from milk collection containers of dairy producers and labeled with essential information such as the date of sampling, sample code, and sample source. Finally, all samples then immediately transported using an icebox filled with ice to the AAU CVMA microbiology laboratory and enriched with previously prepared BLEB immediately upon arrival.

Isolation and Identification of Listeria Species

According to a suggestion by U.S. Food and drug administration [24], 25 ml of raw milk samples were added to a plastic bag containing 225 ml of Buffered Listeria Enrichment Broth (BLEB) (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England). The mixture was then mixed using a laboratory stomacher at maximum speed for 2 minutes. After 4 hours of incubation at 30 oC, Listeria selective enrichment supplement SR0141 (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) was aseptically added and the incubation step continued for up to 48 hours at 30oC. Loopful of inoculum from turbidly grew colonies in buffered Listeria enrichment broth was taken and streaked into pre-dried sterile plates of PALCAM agar (HIMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd. Mumbai-400086, India) prepared after aseptically adding sterile Listeria Selective Supplement FD061 (HIMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd. Mumbai-400086, India) and incubated at 37 oC for 24-48 hours. Typical colonies of grey-green with a black sunken center and a black halo were isolated as typical for Listeria. Selected colonies were further confirmed by Latex agglutination and biochemical tests to confirm as Listeria species, Listeria suspected colonies from PALCAM agar were taken and identified using latex agglutination test with Oxoid Listeria test kit (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England). The kit contained; Listeria latex reagent, Listeria positive control antigen 0.5ml, 0.85% isotonic saline, preserved with 0.09% sodium azide, and Disposable reaction cards. LLOLAT was done on clear reaction cards. A drop of saline within one circle on the reaction card was added, a loopful of the suspected bacterial colony was mixed with saline on the reaction card using a sterile mixing stick and then one drop of Listeria latex reagent was added, mixed gently using a clean sterilized stick. Finally, agglutination was examined within a maximum of 2 minutes for a positive reaction. Positive colonies were characterized by using Gram’s staining, hemolysis, motility, carbohydrate utilization, and CAMP (Christie Atkins Munch Peterson) tests to confirm as Listeria different species (ISO, [25]).

Antibiogram of L. Monocytogenes

An antibiotic susceptibility test was performed for Listeria isolates by using Muller Hinton Agar (Sisco Research Laboratories Pvt. Ltd. India). The method that was applied for antimicrobial testing is the agar plate antibiotic disk diffusion method, using the Kirby-Bauer technique by 0.5 McFarland Standard [25]. Pure colonies of the isolates were taken from nutrient agar and suspended in Muller Hinton Broth dipped using a sterile cotton swab into it and smears uniformly on the prepared Muller Hinton agar, according to the standard procedure, and then the antibiotic discs (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) were firmly placed on it, and the plates incubated at 37 oC for 24 hrs. Antibiotics discs of commonly used antibiotics such as sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, oxytetracycline, procaine penicillin G, streptomycin, clindamycin, nalidixic acid, cloxacillin, and erythromycin were used for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Finally, the zone of inhibition around the disc was measured using a caliper meter and interpretation is based on criteria of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [26].

Questioner Survey

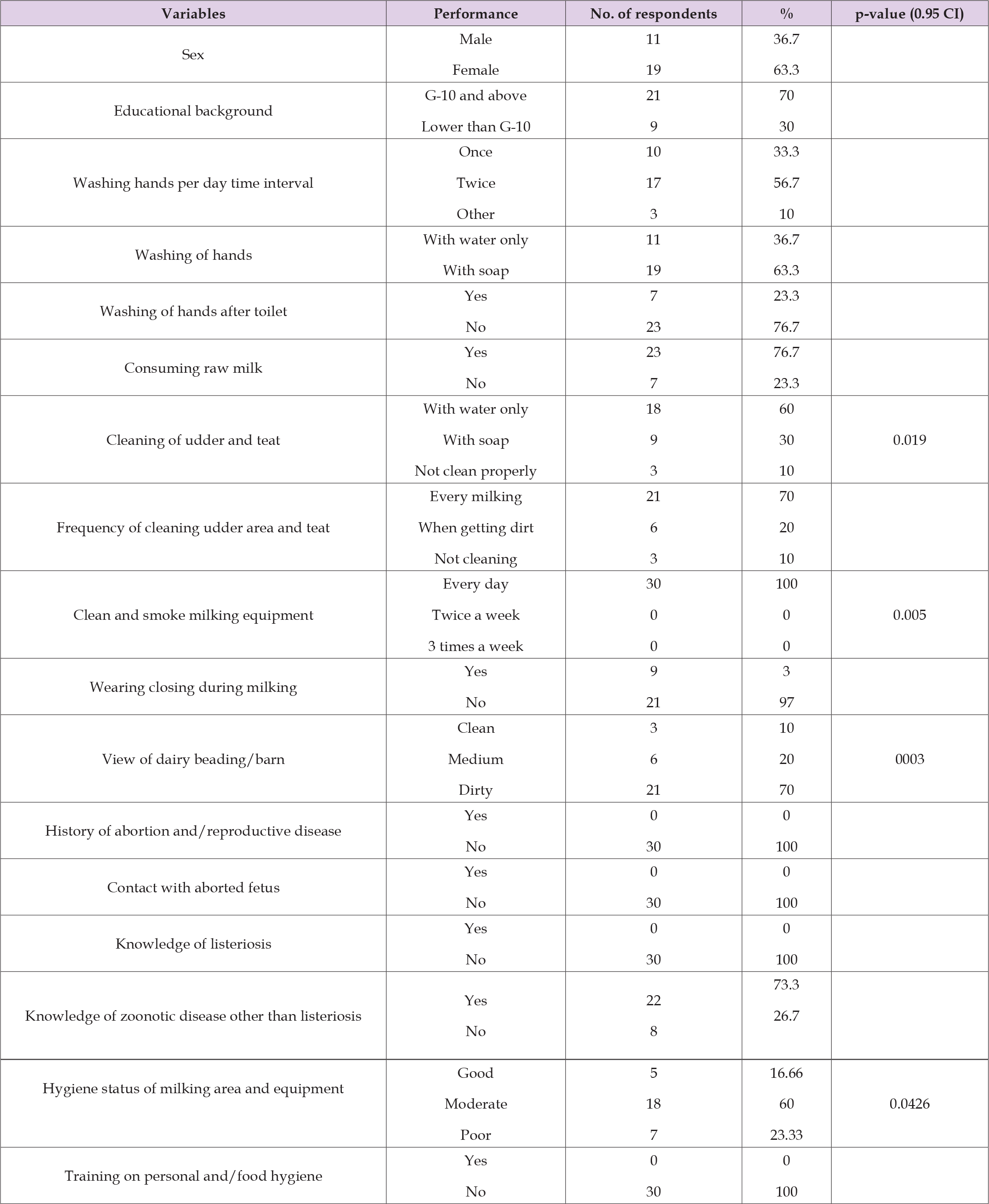

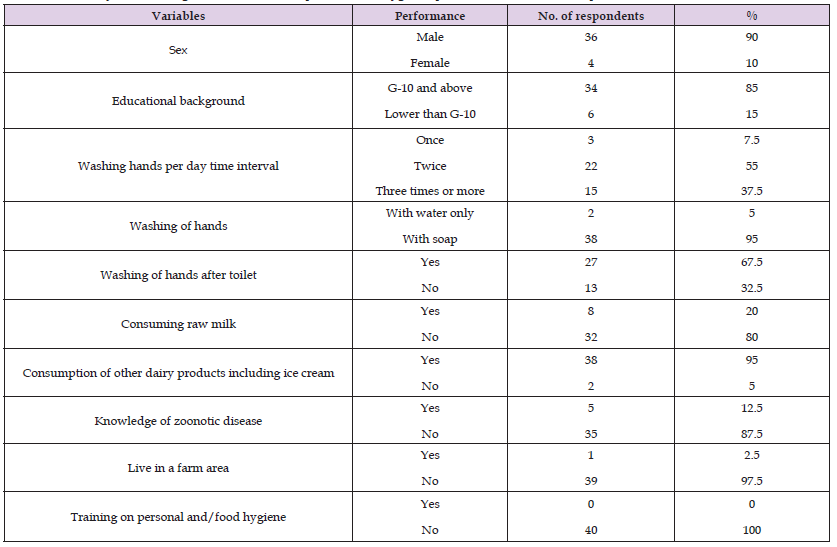

As a part of the research work, a structured questionnaire was used to assess the farm management and practices relevant to infection and transmission of Listeria species in animal and human hosts. Information related to sex, address, educational background, raw milk drinking practice and hygiene practice were collected on a format developed. Using a structured questioner, dairy producers and randomly selected volunteer participants were interviewed. Accordingly, 30 dairy farmers and 40 persons from the community were interviewed. Observational assessments of the farm and milking practice were recorded.

Data Management and Analysis

Microsoft Excel was used for data entry and storage and analysis was done by using RStudio Software (Version 1.4.1106 – © 2009- 2021 RStudio, PBC). Descriptive statistics were used to describe and process the data. Chi-square statistics also used to compare prevalence between groups and to analyze questioner results. The significance level was established at a 95 % confidence interval.

Ethical Declaration

The study was conducted after ethically approved by the AAU CVMA ethical review committee (Date 21/02/2021GC, Ref. No. VM/ ERC/19/5/13/2021) and all study work was conducted according to animal research ethics

From the total of 384 milk samples, the overall prevalence of Listeria species was 49 (12.8%). Which comprised 4% (15/384) for L. monocytogenes, 4.2% (16/384) for L. innocua, 2.1% (8/384) for L. grayi sub spp. Grayi, 1.04% (4/384) for L. grayi sub spp. Murray, 0.8% (3/384) for L. seeligeri, 0.3% (1/384) for L. welshimeri and 0.52% (2/384) for unknown Listeria species. Considering the overall prevalence of Listeria, the high prevalence was found in Kombolcha 13.5% (27/200) and for Kutaber district the prevalence was 12% (22/184). In this case, the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.5). When taking L. monocytogenes, the results were also similar with samples from Kombolcha had the highest prevalence of 4% (8/200) and samples from Kutaber were a prevalence of 3.8% (7/184) (Table 1). Considering the overall prevalence of Listeria species, the high prevalence was found in poorly managed farms (25.5%) and the low prevalence was found in well-managed farms (4.3%). In this case, the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05). The prevalence of listeriosis in differently managed farms showed in the table below (Table 2). Considering the overall prevalence of Listeria species, the highest prevalence was found in farms with 10-15 dairy cows (29%) and the lowest prevalence found in dairy farms with 3-5 cows (5.24%). The difference, in this case, was also found statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Tables 3 & 4).

Note: N = Number of isolates %= Percentage X2 = chi-square CI = confidence interval

Note: No= Number of samples examined Key: Categorizing the herd based on sizes into A. <5, B. 5-10 and C. >10

Note: Km= Kombolcha, Kt= Kutaber, No= Number of samples examined, UK= Unknown species, X2 = Chi-square, V.s= Very small, *= significant

Out of the total of 15 L. monocytogenes species subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility test, 2(13.3%) were equally resistant to oxytetracycline, tetracycline, procaine penicillin G and cloxacillin, and all of the isolates (100%) were resistant to sulfamethoxazole and nalidixic acid. Interestingly all L. monocytogenes isolates 15 (100%) were sensitive to erythromycin and clindamycin. The detailed patterns of susceptibility presented in Table 5. The study showed the multi-drug resistance pattern of isolates. For questioner survey, a total of 70 respondents were used. Out of which 53 were male and 17 of them were female respondents and 77.5% of them were completed Grade 10. From both groups, 56 % and 20.4% of participants washed their hands twice and once daily respectively. And 79 % of them were using soap. Near to half of the respondents (46%) wash their hands after the toilet. Based on findings, 76.7% and 20% of dairy farmers and public respondents consume raw milk respectively and 95 % of respondents from the community consume other dairy products including ice cream. 60 percent of the dairy farmer respondents clean the udder and teat with water only and 30 percent of farmers clean with soap and water and the others not clean properly.

Note: R= Resistant S= Sensitive I= Intermidate

All of (100%) dairy farmer respondents clean and smoke their milking equipment every day. Only about 3% of the respondents wear protective clothing during milking. About 73.3 % and 12.5 % of farmer and public respondents respectively knew about zoonotic disease other than listeriosis. Based on the observational assessment, 70 % of dairy bedding is dirty and 60 % of milking area and milking equipment were in moderate hygienic status. During the survey, no cow showed any reproductive disease signs and no history of abortion was recorded. Detailed questioner findings are presented in the tables below (Tables 6 & 7).

Table 6: Summary of knowledge, attitude and practices of dairy farmers regarding hygiene and listeriosis and observational assessment of the farm.

Table 7: Summary of knowledge and attitude of respondents on Hygienic practice, raw milk consumption and zoonotic disease.

The prevalence of Listeria species in this study is slightly lower than that of the studies reported with a 20.3% prevalence of raw bovine milk from dairy producers in Debre-Berhan town [27] and in central highlands of Ethiopia with a 28.4% prevalence from 443 milk and milk product samples [28]. This could be due to an increase in hygienic practices as raw milk was considered a source of contamination by dairy farmers, processers and consumers, and sample size differences. In the current study, the prevalence of L. monocytogenes was 4.2%. This is in agreement with [29] who noted a prevalence of 4.1%, and Mansouri-Najand, et al. [30] who noted a prevalence of 5%. However, the prevalence of L. monocytogenes is reported higher in other countries like in the USA with 26% [31] and Australia with 40% prevalence [32]. The sensitivity of microbial detection methods and sample size differences could partially explain these differences. In Ghana, the low prevalence of 8.8% [33] was reported. The reason for this is due to different hygienic and sanitary activities in milk supply chains, environmental conditions, and different sample sizes. In Ethiopia, very few studies were done on listeriosis. A report by [34] indicted a prevalence of 5% L. monocytogenes in raw milk and milk product samples from Bishoftu and Dukem towns. Abera, et al. [35] also noted 4.1% of L. monocytogenes from food samples in Addis Ababa. This is also similar to the present study. During this study, isolates of L. innocua and L. monocytogenes were found to be higher as compared with other Listeria species.

This is in agreement with the studies by [36-39]. In Ethiopia, a relatively low prevalence of L. monocytogenes from 873 meat swab samples was reported in Addis Ababa at a 4.1% prevalence [40]. This could be due to hygienic conditions, and sample origins. In this study from both districts, the prevalence of L. monocytogenes was found higher in Kombolcha town. This could be due to a difference in sampling size. In this finding, the prevalence of Listeria species was high in poorly managed and large herd size dairy farms. This might be due to poor hygienic conditions and external contamination via feed, milking equipment, and personnel since the pathogen can multiply and survive up to 7 weeks in dairy manure [41] A study which was done by [42] also reported a high prevalence of L. monocytogenes in reduced ventilation environments as compared to ventilated ones. The reason for the milk samples chosen was Listeria is most prevalent in milk and dairy products [43] Many researchers have been reported the prevalence of Listeria species in raw milk worldwide, in Iran from the total of 240 milk samples 54(22.5%) were positive for Listeria [44]. In Algeria, researchers isolated L. monocytogenes from farm raw milk samples with a prevalence of 2.61% [45] In this study, all 15 L. monocytogenes isolates were analyzed for antimicrobial susceptibility profile. The result showed that all of the isolates (100%) were resistant to sulfamethoxazole and nalidixic acid and about 13.3% of isolates were resistant to oxytetracycline, tetracycline, procaine penicillin G, and cloxacillin.

This is contrary to a report by Garedew, et al. [12] who noted 0% of isolates were resistant to sulfamethoxazole. However, this study showed similar findings to Girma and Abebe [16] who noted 30.5% and 25% of isolates were resistant to nalidixic acid and tetracycline respectively. Another study by Welekidan (2019) stated 66.7% of L. monocytogenes isolated from pregnant women were resistant to procaine penicillin G. This study showed 13.3% of isolates were resistant to oxytetracycline and procaine penicillin G antimicrobial drugs which are commonly prescribed in study areas for the treatment of most bacterial infections. This could be mentioned as one of the reasons for some non-effective treatments with these drugs. The resistance for nalidixic acid and tetracycline was also similar to studies carried in different countries (Pintado, et al. [42,43]). Antimicrobial- resistant L. monocytogenes in raw food products have significant public health implications, particularly in developing countries where antibiotic use is prevalent and uncontrolled (Sharma, et al. [43]). All L. monocytogenes isolates were sensitive to clindamycin and erythromycin. This reveled in agreement with studies by Welekidan [17] and Abera [35]. Both reported 100% of isolates were sensitive to erythromycin. In this study, 87%, 73%, and 60% of isolates were sensitive to procaine penicillin G, oxytetracycline, cloxacillin, and streptomycin respectively. Procaine penicillin G and tetracycline sensitivity were higher than a report by [44].

The sensitivity of L. monocytogenes to streptomycin, procaine penicillin G, tetracycline, and oxytetracycline observed in this study were similar to studies by [16,29,35,37]. Farmers and personnel can contaminate food products with L. monocytogenes if they are not followed proper farm management systems. Poor hygienic practices such as; not wearing personal protective clothing, improper hand washing, not cleaning equipment and working areas properly can result in contamination of foods with L. monocytogenes [45]. The results of this study showed that most of the respondents (79%) wash their hands daily with soap and 46 % of respondents wash their hands after the toilet. This is in agreement with a previous study which revealed that 80% of respondents use detergent for washing their hands [29]. However, a report by Mulu [29] showed 94% of respondents wash their hands after using a toilet. Concerning dairy farmers, 60% of the respondents clean the udder area and teat with water only, 30% were using soap to clean and 10 % were not clean properly. This could be a reason for Listeria species prevalence in raw bovine milk. Concerning personal and/food hygiene training, this report showed that all respondents were not taking the training yet. This is contrary to previous studies [29,44].

This study revealed that consumption of raw milk is higher in dairy farmers which showed a high risk of getting an infection with L. monocytogenes. Interestingly, since consumption of raw meat, milk and milk products is very common and large amounts of high-risk population are found the problem can be higher in Ethiopia. In this finding prevalence of Listeria was found higher in farms not practicing cleaning of udder and milk equipment. This might be due to the easy transmission and survival of the pathogen from the environment to dairy cows since the origin of L. monocytogenes contamination in milk is mainly of faeces [46]. About 73.3 % of dairy farmer respondents knew about zoonotic disease other than listeriosis. This could be due to they learn about those diseases when they got service in veterinary clinics.

The microbiological laboratory examination of these samples in this study revealed that the significant presence of L. monocytogenes comparing with other Listeria species. This existence of L. monocytogenes in raw milk and its multi-drug resistance pattern is an indication of a serious public health hazard for raw milk and milk product consumers especially to high-risk groups such as; pregnant women, immunocompromised individuals, young and elderly. Due to the increase of multi-drug resistance showed by L. monocytogenes isolates, continuous surveillance of drug resistance is important for effective treatment. The questioner findings in this report showed that most dairy farmers and some public respondents consume raw milk. Associated with the probable risk of getting infected with Listeria is higher with increased consumption of raw milk and milk products, this emphasizes the impact of listeriosis in public health and the need for strong control and prevention strategy.

We would like to thank Addis Ababa University for funding and laboratory facility support for smooth accomplishment of this research. In addition, we want to acknowledge to all dairy farmers, zonal and wereda animal production experts who participated in this study. Without the cooperation and interest shown by them, the study would not have been possible.

No competing of interest.