Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Babatope IO1*, Esumeh FI2, Okodua MA3, Iyevhobu KO3, Uadia MO1, Eromosele VO1, Idehai FA1, Ogbomo JO1, Moses OR1, Enabor CE1, Egbe EA1, Nosakhare IS1, Eze G1 and Arianele NE1

Received: November 04, 2024; Published: November 15, 2024

*Corresponding author: Babatope IO, Department of Haematology and Blood Transfusion Science Faculty of Medical Laboratory Science, Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.59.009310

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and/or the Hepatitis C virus (HCV) are public health problems, which are highly endemic in the sub-Saharan Africa countries where Nigeria is located. This study was carried out to determine the seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C viruses among the students of a state-owned university in South South Nigeria. A total of two thousand (2000) apparently healthy students of Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State, aged 16 to 35 years and of both sexes were recruited for this study. HBV and HCV serostatus were determined using a qualitative, lateral flow immunoassay test kit devices for the detection of both HBSAg and HCV in plasma (Diaspot Diagnostic Inc., U.S.A.). Data generated were presented in simple proportion and were analyzed for statistical relevance using Pearson’s Chi-square. Of the 2000 subjects screened, 1.2% and 0.55% were seropositive for HBV and HCV respectively. The sex related HBV prevalence rates of 0.8% and 0.4% were recorded for the male and female subjects respectively. Similarly, the seroprevalence rate of HCV with respect to sex revealed 0.2% and 0.35% for male and female subjects respectively. Age distribution of HBV prevalence showed that subjects belonging to the age group of 21-25 years had the highest prevalence rate of 0.65%, followed by 26-30 years (0.45%) and 16-20 years (0.1%) while age group 31-35 years recorded a zero pre valence rate. Furthermore, the HCV age related prevalence for the age groups of 16-20 years, 21-25 years, 26- 30 years and 31-35 years were 0.1%, 0.3%, 0.15% and 0% respectively. In conclusion, the results of this study showed a low prevalence for both HBV and HCV among the subjects studied. We hereby recommend screening for early detection and initiation of treatment in other to prevent further transmission of these viruses.

Keywords: Hepatitis B Virus; Hepatitis C Virus; Seroprevalence; Ekpoma

Viral hepatitis is one of the major public health concerns around the world [1]. Both hepatitis B and hepatitis C can lead to lifelong infections [2]. Every year viral hepatitis – related cirrhosis and liver cancer occur with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) causing 90% of the fatalities and the remaining 10% caused by other hepatitis viruses [3-5]. The World Health Organization [2] estimated that during 2019, 296 million people worldwide are living with hepatitis B and 58 million people worldwide are living with hepatitis C. It has also been estimated that 1.5 million people were newly infected with chronic hepatitis B and 1.5 million people were newly infected with hepatitis C. Furthermore, it has been estimated 1.1 million deaths occurred due to the infections and the effects caused by chronic viral hepatitis [2]. HBV is an enveloped virus which belongs to hepadnaviridae: with circular partially double stranded DNA representing highly compact organization. The HBV is the smallest known DNA virus, having spherical shape with a diameter of about 42 nm and genomic length of approximately 3.2 kb [6,7]. The infectious viral particle in responsible for causing infection in approximately five percent of world’s population with 2 billion people infected with the virus and 350 million as carriers of chronic infection [8]. The virus is responsible for 600,000 deaths each year [9-11]. On the other hand, HCV has been classified into the genus hepacivirus of the family Flaviviridae [12]. This virus is responsible for causing infection in three percent of world’s population with approximately 170 million persons at risks of developing chronic hepatitis [13]. The HCV is a small spherical enveloped virion with icosahedral capsid. The structure consists of an icosahedral lipid membrane with 2 glycoproteins (termed E1 and E2) that form heterodimers. An icosahedral nucleocapsid is thought to be present inside the viral membrane [14]. In Nigeria, about 20 million people are infected, this figure makes Nigeria to be classified among the group of countries ranging from 2.2% - 65.9% [15]. Also, in Nigeria, screening of tertiary institutions students for HBV as well as HCV is not a routine practice. Furthermore, routine vaccination of students with HBV vaccines is not widely available especially in low resource countries as Nigeria [16]. With respect to risk factors, poor social-cultural practices, unprotected sex and poor hygiene are most of the factors predisposing Nigerians in contracting the disease [17]. These youths are known to be a group that is highly at risk because of their high sexual activity in addition to the fact that they form the bulk of the group that is usually required when there is need for blood donation [18]. Recent estimates indicate that majority of the chronically infected population remains undiagnosed [19-21]. With respect to Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C virus, different seroprevalence studies have been reported by different authors among tertiary institutions students in some parts of Nigeria such as Zaria, Kaduna State [16], Minna, Niger State [22], Anyigba, Kogi State [23], Owo, Ondo State [24], Ilorin, Kwara State [25], Bayelsa State [26], Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria [27], Ilishan-Remo, Ogun State [28], Oye-Ekiti, Ekiti State [29] and Abakaliki, Ebonyi State [30].

But information on the seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C virus infections in the study area appears scarce in literature. Therefore, the study was aimed at determining the seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C viruses among the students of a Stateowned university in South-South Nigeria.

Study Area

This study was carried out in Ekpoma. Ekpoma is the headquarters of Esan West Local Government Area of Edo State which falls within the rain forest/Savannah transitional zone of South Western Nigeria. The area lies between latitudes 60 431 and 60 451 North of the Equator and longitudes 60 51 and 60 81 East of the Greenwich Meridian. Ekpoma has a land area of 923 square kilometers with a population of 170,123 people as at the 2006 census [31]. The town has an official post office and it is the home of Ambrose Alli University.

Study Population

A total of two thousand (2000) apparently healthy students (of Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma) aged 16-35 years and of both sexes were recruited for this study.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee of Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma (NHREC registration number: NHREC 12/06/2013). Informed consent was sought from each participant before sample collection.

Inclusion Criteria

Apparently healthy students without jaundice, with no history of blood transfusion or past HBV or HCV infection were included in this study.

Exclusion Criteria

Individuals that have been confirmed HBsAg and HCV positive and on antiviral medication, had previous history of blood transfusion, had or has jaundice or have any apparent ill-health were excluded from the study.

Sample Collection

Two millilitres (2ml) of venous blood was collected from each subject via venipuncture into an EDTA container under aseptic conditions. Each blood sample was spun with a centrifuge at 2,000 rpm for 5 minutes at room temperature. All the samples were treated within 2 hours of blood collection. Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C screening were carried on each of the serum samples.

HBV and HCV Screening

The samples were screened for HBsAg and HCV using Diaspot one step hepatitis B surface Antigen test strips and Diaspot one step hepatitis C test strips respectively (Diaspot Diagnostics Inc., U.S.A.). These are qualitative lateral flow immunoassay test kit devices for the detection of both HBsAg and HCV in plasma with a relative sensitivity of 99.0% and relative specificity of 98.6%. The tests were done according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Positive and negative controls were included in each batch of the tests to confirm test procedure and also to verify proper test performance.

Data Analysis

The prevalence of HBV and HCV was determined from the proportion of seropositive subjects in the total population under study and expressed as percentage. Pearson’s Chi square was used to test for the independence of each frequency distribution and observed to be significant at p ≤ 0.05.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study Population

The socio-demographic characteristics of the study population is shown in Table 1. The subjects were categorized into four age groups namely 16-20 years; 21-25 years; 26-30 years and 31-35 years. According to age, 62.5% of the subjects were within the age range of 21 - 25 years, followed by 26-30 years (17.95%), 16-20 years (17.1%) and the least being 31-35 years (2.45%). The age (mean ± SD) of the subjects was 25.41±3.02. With respect to gender, 57.75% were females while the remainder (42.25%) of the subjects were males. Based on religion, 96.5% were Christians and 3.5% were Muslims. According to marital status, 98.0% of the subjects were single and married subjects accounted for 2.0%. Furthermore, 85.0% of the subjects do not consume alcohol while 15.0% consume alcohol.

Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and C Viruses in the Study Population

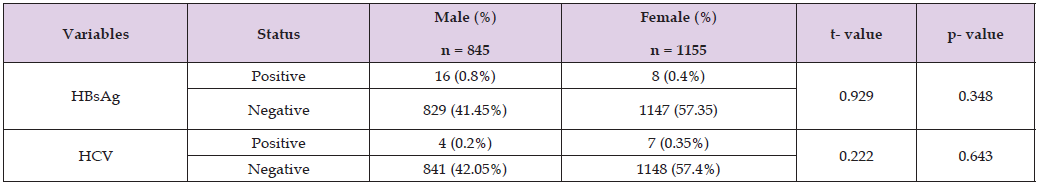

Table 2 revealed the Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and C viruses in the study population. With respect to HBsAg, the seroprevalence rate was 1.2%. On the other hand, the seropositivity of HCV was 0.55%. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and C viruses in the study population with respect to gender Table 3 showed the seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and C viruses in the study population in relation to gender. With respect to HBsAg, the male and female subjects noted seropositivity rates of 0.8% and 0.4% respectively. Statistical comparison did not reveal any statistical significant difference (p>0.05) between both sexes. In the same vein, the seroprevalence of HCV for the male and female subjects were 0.2% and 0.35% respectively. Statistical comparison did not reveal any significant (p>0.05) between the male and female subjects with respect to HCV infection.

Note: Keys: HBsAg = Hepatitis B surface Antigen

HCV = Hepatitis C Virus

Table 3: Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and C viruses in the study population with respect to gender.

Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and C viruses in the study population based on age

Table 4 shows the seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and C viruses in the study population based on age. The HBsAg seropositivity of 0.1%, 0.65%, 0.45% and 0% in the respective age brackets of 16-20 years, 21-25 years, 26-30years and 31-35 years. Statistical comparison revealed that there was no significant difference (p>0.05) between HBsAg positivity and age. On the other hand, HCV seropositivity of 0.1%, 0.3%, 0.15% and 0% were recorded in the age groups of 16-20 years, 21-25 years, 26-30 years and 31-35 years respectively. Statistical comparison between HCV and age did not reveal any significance (p>0.05).

Note: Keys: HBsAg = Hepatitis B surface Antigen

HCV = Hepatitis C Virus.

Screening asymptomatic people for underlying diseases is an important approach in disease detection, prompt prevention and intervention especially when silent killer disease agents like HBV and HCV infections are involved or suspected [32]. Furthermore, an understanding of the global and regional epidemiology and burden of hepatitis B and C infection with respect to the main routes of transmission, most affected populations and naturally history and time course of serological markers is critical to inform strategies on both who to test and how to test [33]. In this study, the seroprevalence of HBV was 1.2%. The overall HBV seroprevalence rate observed in our study correlates with that of Enitan et al. [28] who reported HBsAg positivity rate of 1.5% among students of a private tertiary institution in Ogun state, South Western Nigeria. The reason for the low prevalence we noted in our study is not clear but we are inclined to infer that most of our subjects belong to the low-risk group and appear to have a good knowledge of HBV transmission. Other reasons might not be unconnected with the geographical location of the study population and their socio-cultural practices among others. In contrast, our result was at variance with the previous report of Ojerinde et al. [29] who found a prevalence of 2.23% among students of a tertiary institution in Ekiti State, Southwest Nigeria. Correspondingly, other authors such as Adabara et al. [22], Bello et al. [25], Isa et al. [16] and Nwodo et al. [26] have reported respective HBV seroprevalence rates of 4.3%, 5.5%, 9.2% and 10.1% in various studies they carried out among students of different tertiary institutions in Nigeria.

The reasons for the variations observed across the various universities’ reports may be due to factors such as illicit intravenous drug, blood transfusion and unprotected sexual intercourse that have been documented as risk factors for HBV infection [34]. In addition, poor adherence to vaccination schedule, relatively low vaccination coverage and sharing of drinking cups may have also favoured HBV transmission in the aforementioned areas [35]. The seroprevalence rate of 0.55% was reported for HCV in the study area. Our finding correlates with that of Bello et al. [36] who reported a 0.6% HCV seroprevalence rate among participants in the Kwara State Polytechnic, Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria. Similarly, Olabowale and Adebayo [37] reported a seroprevalence rate of 0.7% for HCV antibody among the teenage students of a private university in Ogun state, Nigeria. However, our result disagrees with the earlier reports of Oluboyo et al. [27] and Muhibi et al. [24] who both found a zero percent HCV seroprevalence rate among the tertiary institution students they studied in Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State and Owo, Ondo state, Nigeria respectively. In a similar fashion, Bello et al. [36] also reported a zero percent HCV prevalence rate among participants in the College of Education, Oro, Kwara State, Nigeria. The reason for the low HCV seroprevalence rate observed in our study is not clear but the differences might not be unconnected with the fact that the majority of the subjects we studied belonged to low-risk group. As earlier stated, the geopolitical location of the study population and their socio-cultural practices might be some of reasons responsible for this.

On the other hand, slightly higher prevalence rates of 1.4% was reported in an earlier study done by Ogefere et al. [38] among students of a public university in Benin, Edo State, Nigeria. Moderate seroprevalence HCV rates of 4.0% and 5.2% have been reported by Dawurung et al. [32] and Usanga et al. [30] in separate studies carried out in the University of Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria and Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Ebonyi State, Nigeria respectively. Higher HCV prevalence of 15% was reported by Mbah et al. [39] among the students of University of Calabar, Cross Rivers State, Nigeria. The higher HCV seroprevalence rates reported by these authors compared to ours can be attributed to differences in sample size, the sensitivity and reliability of viral assay reagents, the category of people studied, geographical location of the study population and socio-cultural practices might be some of the contributory factors. On the basis of gender, the seroprevalence rate of HBsAg was higher (0.8%) in male subjects compared to their female counterparts (0.4%). Previous authors have reported a similar pattern although higher rates of infection. For example, Dawurung et al. [32] found the gender-related prevalence of HBsAg among the university of Maiduguri students to be 5.7% for males and 2.6% for their female counterparts. Similarly, Enitan et al. [28] reported respective prevalence of rates of 2.1% against 1% for male and female subjects in Babcock University Ilishan-Remo, Nigeria. No concrete explanation can be given for a higher vulnerability of males to the infection than females.

Nonetheless, as prior mentioned, the variation might be caused due to differences in the geographical location of the study population and socio-cultural practices among others. In contrast, the previous report of Oluboyo et al. [27] observed that according to gender, the seroprevalence of HBV was higher (28.9%) in females compared to males (17.4%). Similarly, Adabara et al. [22] revealed a gender distribution of HBV infection to be 5.5% and 3.0% for female and male subjects respectively. Socio-economic, cultural, biological factors might be responsible for the female gender’s vulnerability to HBV. Royce et al. [40] reported that during unprotected vaginal intercourse, a woman risk of becoming infected with HBV may go up to 4 times higher than the risk of man. Furthermore, the seroprevalence of HCV based on sex is 0.35% and 0.2% for the female and male subjects respectively. Our finding is in accord with earlier studies of Usanga et al. [30] who reported that 5.9% of female subjects were seropositive for anti-HCV antibody in comparison to male subjects (4.5%). In another study, Mbah et al. [39] reported that the prevalence of anti-HCV antibody was significantly higher in females (18.8% than males (13.2%). As earlier mentioned, socio-economic, cultural, biological factors might be responsible for the female gender vulnerability to HCV. Furthermore, Royce et al. [40] reported that during unprotected vaginal intercourse, woman’s risk of becoming infected with HCV may go up to 4 times higher than risk of man.

On the other hand, Dawurung et al. [32] reported the gender-related prevalence of HCV to be 4.9% in males and 2.6% in females. No apparent reason can be given for this, but the variation might be caused as prior mentioned due to differences in geopolitical location of the study population and socio-cultural practices. Subjects in the age range of 21-25 years recorded the highest HBV seroprevalence of 0.65% followed by individuals belonging to the age groups 26-30 years who had 0.45% while seroprevalence rates of 0.1% and 0% were obtained for the respective age groups of 16-20 years and 31- 35 years. Our result concurs with the earlier reports of Adabara et al. [22] who reported the highest HBV seroprevalence of 8.1% among subjects in the age group of 21-24 years compared to the other age groups they studied. Nwodo et al. [26] also reported that the highest prevalence of HBsAg infections was observed in participants aged 26- 35 years, demonstrating statistical significance. Furthermore, Agbana et al. [23] observed that about one quarter (15.2%) of those in the age group 26-30 years were positive for HBsAg compared with less than one tenth (3.1%) of the respondents. Considering the age group most affected in this study, one can infer that it correlates with the age of greatest sexual activity thus lending credence to the role of sexual transmission [41]. Tattooing, nose and multiple ear piercing are some of the common practices this age group indulge in because of reduced parental control and the increased freedom they enjoy in the university environment.

In contrast, Enitan et al. [28] reported that the age group of 16-20 years had a seroprevalence of 2.7% for HBV while the other age groups recorded zero percent. Oluboyo et al. [27] also reported that a higher prevalence of HBV was recorded among students between the ages of 16 to 20 years in relation to students in ages 21-25 years with the difference being statistically significant. According to Dawurung et al. [32], prevalence for HBsAg was higher (5.4%) in subjects in the age group of 18-25years compared to 26-45 years (3.4%). In the present study, subjects with highest HCV seroprevalence rate of 0.3% belonged to the age group of 21-25 years followed by 26-30 years (0.15%) compared to other age groups studied. Our result corresponds with the earlier studies of Dawurung et al. [32] who found age related prevalence of HCV to be 5.7% and 2.7% among those aged 26-46 years and 18 - 25 years respectively. Our result is also aligning with the reports of Usanga et al. [30] who found that participants within the ages of 21-25 years had the highest seroprevalence (6.0%), followed by those in the age group 26-30 years and those within the ages of 31-35 years (5.8%) while age group 16-20 years had the least seroprevalence of 3.1%. Furthermore, Ogefere et al. [38] observed that students aged 21-24 years and 17-20 years had the highest rate of HCV infection of 1.7% and 2.1% respectively.

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that the seroprevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections to be of low prevalence among the subjects studied. Regardless of the low prevalence rates obtained in this study, we recommend screening for early detection and initiation of treatment in other to prevent further transmission of these viruses.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and the writing of the paper.

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The entire study procedure was conducted with the involvement of all writers.