Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Gaziza Hassan Marouf1, Hisham Arif Getta2, Ahmed Farhan Shallal3 and Aveen M Raouf Abdulqader4*

Received: November 01, 2024; Published: November 12, 2024

*Corresponding author: Aveen M Raouf Abdulqader, Medical Microbiology Department, College of Health Science, Cihan University Sulaymaniyah, KRI, Iraq

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.59.009301

Background: Iron deficiency is frequent in female athletes due to greater turnover of red blood cells during

exercise. Negative iron balance associated with inadequate dietary iron intake, menstruation, and other factors

such as hemolysis, sweating, and exercise-induced acute inflammation are also contributing factors. Therefore,

female athletes are considered to be at a greater risk of iron disturbance, which may lead to iron deficiency anemia

or latent iron deficiency.

Objective: This study was aimed to determine the frequency of iron deficiency in female athletes in Sulaymaniyah

city

Methods: A total of 140 healthy habitual female athletes were screened for eligibility. One hundred and twenty

were eligible and participated in the current study. Sampling was collected based on a stratified sampling method.

Blood samples were taken from the participants in 23 Sports centers based on socioeconomic distribution.

The parameters included complete blood counts (CBC), serum ferritin, serum iron, total iron-binding capacity

(TIBC), and unsaturated iron binding capacity (UIBC).

Results: Based on ferritin level, 25 (20.8%) of the participants were having low ferritin (<10 ng/ml), and they

were classified as being iron deficient. While 95 (79.2%) of the participant were having normal ferritin level

(10-291 ng/ml). Only 16 (13.3%) of the participants practiced exercise for a long duration (6-12 years). Around

half of them were found to have iron deficiency anemia. A highly significant difference was observed between

the three-duration scale of exercise [(1-6), (6-12), (12-18)] years; (p-value <0.05) regarding iron deficiency. The

relation between menstrual pattern with iron deficiency has been investigated. The result showed that there was

no significant relationship (p-value >0.05) between menstrual pattern and iron deficiency with or without anemia.

Additionally, a non-significant difference between the stated categories of BMI and iron deficiency states of

the female athletes (p-value =0.487) was found. In spite of a remarkable number of the athletes who were taking

supplements 48 athletes (40%), about a quarter 12 (25%) were iron depleted. Meanwhile, less iron-deficient

athletes 11 (15%) were seen in the groups who were not taking any dietary supplements.

Conclusions: The frequency of iron deficiency with or without anemia among female athletes is remarkable

which necessitates establishing a screening program to reduce its detrimental impact on health and physical

performance.

Keywords: Total Iron-Binding Capacity; Blood Elements; Ferritin, Anemia; Supplement

Abbreviations: CBC: Complete Blood Count; SI: Serum Iron; SF: Serum Ferritin; TIBC: Total Iron Binding Capacity; UIBC: Unsaturated Iron Binding Capacity; SPSS: Statistical Package For Social Sciences

Anemia is defined as low hemoglobin concentration with decrease in oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange between blood and tissue [1]. The World Health Organization has defined anemia in women as hemoglobin concentrations less than 12.0 g/dL and <13 g/ dL in men [2]. There are three stages in iron deficiency progression, iron depletion, iron deficiency and finally iron deficiency anemia. [3]. Iron depletion start when serum ferritin is reduced but hemoglobin and red cell indices are normal. Iron depletion maybe three times as common as iron deficiency anemia which has a prevalence of 2-5% of adult men and postmenopausal women in the developed world. Iron depletion is more common in the developing world especially amongst women because of menstruation [4]. Iron concentration in body tissues is tightly regulated because excessive iron leads to tissue damage. Disorders of iron metabolism are among the most common diseases of humans and present in a broad spectrum of diseases with diverse clinical manifestations, ranging from anemia to iron overload [5]. Iron has several vital functions in the body. It serves as a carrier of oxygen to the tissues from the lungs by red blood cell hemoglobin, as a transport medium for electrons within cells, and as an integrated part of important enzyme systems in various tissues [6]. Iron is required for numerous vital functions, including oxygen transport, cellular respiration, immune function, nitric oxide metabolism, and DNA synthesis. Iron is also vital in neurochemical circuits and emotional behavior and it acts as a promoter against the production of harmful free-radical [7,8].

Iron deficiency is frequent in female athletes; this is because of a greater turnover of red blood cells during exercising, negative iron balance associated with inadequate dietary iron intake, menstruation also seem to be play in important role due to the blood loss and other factors like hemolysis, sweating, gastrointestinal bleeding and exercise- induced acute inflammation [9]. Therefore, female athletes are considered to be at a greater risk of iron status disturbance, which may lead to iron deficiency anemia or iron deficiency without anemia. The prevalence of iron deficiency is higher in physically active individuals and athletes, in comparison to the sedentary population [10,11]. Higher deficiencies in iron storage have been reported in adolescents [12]. Especially in female athletes, the prevalence of iron disorders is up to five to seven times higher than their male homologs [13, 14].

Subjects and Design

This was a prospective observational study that was carried out between November 2018 and March 2019 at the sport centers in Sulaymaniyah District. There were 82 sports centers (23 for females and 59 for males) in Sulaymaniyah. Written informed consent was taken from all the participants entailing the purpose of the investigation and ensuring the confidentiality of the results. All-female athletes provided a written formal consent to participate in this study. Centers were formally assigned by the General Directorate of Sport in Sulaymaniyah. Sampling was collected based on a stratified sampling method 23 female sports centers were officially available in the city, all centers were permitted to participate in the current study except one of them not given consent. The geographical distribution of the centers was as follows: 11 of them from the high socioeconomic area, 8 were from medium while 4 from the low socioeconomic area. Demographic data and basic characteristics of the participants were taken by using a structured assisted questionnaire including age, body weight, and height for measuring body mass index, duration of exercise according to three patterns 2, 2.5, and 3 hours of exercise per day regularly (minimum 3 days per week), history of period (menses) classified into three categories heavy (more than 60ml per cycle ) the menstrual lasts more than 5 days, Normal menstrual cycles (defined as 9-12 menstrual cycles per year with cycles occurring at regular intervals < or =to 30ml ) [14,15].

Materials

All the chemicals; the diagnostic kits for hematological and biochemical analysis are shown the Table 1.

Methods

Laboratory tests (variables) include complete blood count (CBC), serum iron (SI), serum ferritin (SF), total iron binding capacity (TIBC), unsaturated iron binding capacity (UIBC), Percent of transferrin saturation was calculated by: serum iron x100/TIBC also UIBC = TIBC – serum iron. MYTHIC 18 Fully automated hematology analyzer was used to test hematological parameters while, the serological parameters measured by Cobas e 411 Roche- HITACHI Analyzer.

Statistical Analysis

The collected data was reviewed and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social sciences (SPSS version 22). Descriptive statistics such as frequency and percentage were calculated. Measures of central tendency and dispersion around the mean were used to describe continuous variables. P value was obtained for the continuous variable using chi square and was considered significant if it was less than 0.05.

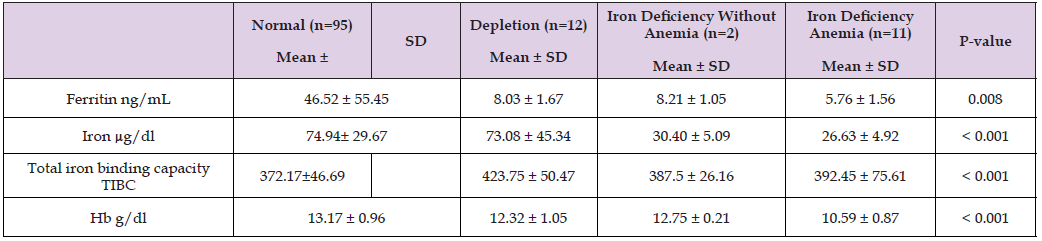

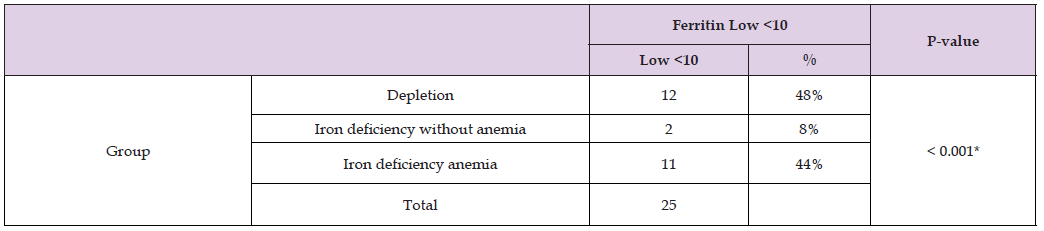

The personal sociodemographic characteristics of the female athletes are given in Table 2. Table 3 clarifies the adoption of serum ferritin as an indicator of iron stores and its comparison with other indicators of iron deficiency anemia to describe the stages of iron deficiency in athletes registered among all participants while Table 4 showed that among female athletes with low serum ferritin n=25; 12 (48%) of them were iron-depleted and classified as the first stage of iron deficiency and 2 (8%) of them were having iron deficiency without anemia classified as the second stage of iron deficiency and 11 (44%) of them were having iron deficiency anemia. Table 5 illustrates the distribution of normal and iron deficiency including those with iron-depleted, iron deficient without anemia, and iron deficient with anemia versus three duration ranges of practicing exercise (1-6), (6- 12), (12-18) years. Table 6 shows that there was no significant relationship (p-value >0.05) between a history of the period (menstrual pattern) and iron deficiency with or without anemia. As shown in Table 7 the result reveals that there was a non-significant difference between the stated categories of BMI and iron deficiency states of the female athletes (p-value =0.487). As illustrated in Table 7 number of the athletes who were taking the supplements 48 (40%), about a quarter 12(25%) were iron deficient including 7 had iron depletion, 2 had iron deficiency without anemia, and 5 had iron deficiency with anemia. Meanwhile less iron- deficient athletes 11(15%) were seen in the groups who were not taking any dietary supplements Table 8.

Table 3: Laboratory investigations of Iron Deficiency Parameters in Female Athletes in Sport Centers in Sulaymaniyah City n=120.

Table 4: Distribution of Iron Deficiency with or without anemia among participant with low ferritin level n=25.

Iron deficiency has become a growing concern of health sectors in the world, premenopausal women are mostly suffered from an iron deficiency with anemia and without anemia, although the prevalence and frequency of iron deficiency without anemia are more prominent in sedentary premenopausal women [16]. Serum ferritin levels are strongly correlated with iron stores in the bone marrow [17,18] therefore, low levels of serum ferritin indicate latent iron deficiency. In the present study, the frequency of iron deficiency among female athletes has remarkably noted (20.8%) as defined by serum ferritin less than 12-20 ng/ml, [19] as well as non-overt anemia has been recorded for the profound number of the female athletes in the surveyed centers. The current results are comparable to the findings stated by other researchers in various studies including the randomized controlled trials who have highlighted the high prevalence and variety reasons of iron deficiency inactive women and they recommended that female athletes are most at risk of iron deficiency [20]. Chronic exercise or long-duration exercise plays a significant role in the alteration of several hematological variables in strength-trained athletes [21]. The principal finding of the present study reveals that athletes with more duration of exercise (6-12 years) show higher percentages (75%) of iron deficiency in comparison with the numbers recruited with less duration of exercise (11%).

Menstruating women lose approximately 1 mg per day of iron when bleeding. This may be higher in heavy menstrual bleeding, where blood loss is estimated to be 5- 6 times greater [22]. The present study described the female athlete’s menstruation types with three different patterns (heavy, regular-medium, irregular- light) using the structured questionnaire and assessment of menstrual blood loss by pictograms with blood loss equivalent a non- significant relationship (p-value >0.05) between menstrual pattern and iron deficiency with or without anemia was observed. This result was inconsistent with the recent finding whose state that heavy menstrual bleeding is prevalent in athletes at all levels [23]. In the present study, a non-significant association was found between weight status reflected by BMI and iron deficiency states of the female athletes (p-value =0.487) using ferritin as an index of iron deficiency among the participants. This finding was non-comparable with an early study, which stated that there is an inverse association between BMI and serum ferritin. Consequently, overweight adolescents in this study were demonstrated an increased prevalence of iron deficiency anemia. Meanwhile, a recent study reported that plasma ferritin level is positively associated with BMI in the obese but not in the individuals with normal weight [24]. Ferritin level in obese adolescents seems not to reflect body iron storage [25]. The suggested mechanism for the positive relationship of obesity with ferritin is verified through a growing document that supports the idea of the obesity-related inflammatory process can increase ferritin levels [26]. Even with depleted iron stores [27,28].

The result of the present study revealed that approximately onethird of the participants (40%) were athletes-consuming dietary supplements and almost all of the dietary supplements consumed by the female athletes were not containing iron elements. Consequently, non-significant differences (p-value =0.129) were found between the athletes taking a dietary supplement and those who were not taking them concerning iron deficiency. This finding is inconsistent with the earlier data of female athletes showing that more than 50% consume iron-containing dietary supplements [29]. This study found that the frequency of iron deficiency with or without anemia among female athletes is remarkable which necessitates establishing a screening program to reduce its detrimental impact on health and physical performance. Non-overt anemia has been recorded for the profound number of female athletes in the surveyed sports centers. The principal finding of the present study reveals that athletes with more duration of exercise show higher percentages of iron deficiency in comparison with the numbers recruited with less duration of exercise. Type of sports activity, menstruation pattern, and body mass index imposed non-significant association with iron level and frequency of iron deficiency, although further study recommended for determining their role in iron status and anemia in female athletes. Almost all dietary supplements consumed by the participants were a non-iron containing formula that needs regular follow-up to identify athletes who require iron-containing supplement with the one not containing iron moiety to avoid the risk of iron deficiency anemia or iron overload.