Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Francesco Maria Bulletti1, Maurizio Guido2, Antonio Palagiano3, Maria Elisabetta Coccia4 and Carlo Bulletti5*

Received: September 16, 2024; Published: September 26, 2024

*Corresponding author: Carlo Bulletti, Associate Professor Adjunct, Department Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Science, Yale University New Haven (Ct) USA, and Director of Help Me Doctor a Worldwide Platform for 1st and 2nd medical Opinions. Cattolica (Rn), Italy

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.58.009214

Endometriosis affects around 10% of reproductive-age women, causing severe pain, infertility, and various other symptoms. Traditional treatments, like hormonal therapies and surgeries, often provide temporary relief with significant side effects, The disease’s heterogeneity and varied responses to treatment necessitate a personalized approach. The leading hypothesis for endometriosis onset and recurrence is retrograde menstruation, influenced by factors like uterine position, tubal filtering function by its length and opening sizes, and specific uterine contractility profiles. This hypothesis suggests that only some women are predisposed due to these factors, leading to endometrial cell regurgitation into the pelvic cavity. Advances in biophysical and biochemical markers (proteomics and metabolomics) offer insights into disease activity and treatment response, enabling real-time monitoring and personalized care. Targeted therapies, including angiogenesis inhibitors and drugs/devices modulating hormonal and inflammatory pathways, and uterine content outflow through adequate cervical/ tubal openings and uterine contractions control, promise to enhance outcomes and quality of life.

Keywords: Endometriosis; Pathogenesis; Theory; Epidemiology

Background Information

Endometriosis is characterized by the growth of tissue resembling the lining of the uterus in areas outside the uterus, such as the ovaries, fallopian tubes, bladder, intestines, or peritoneum. It can less commonly affect areas outside the pelvis, like the diaphragm, pleura, abdominal wall, or nervous system [1,2]. This condition causes severe pelvic pain and can make it difficult to conceive. About 10% of women and girls of childbearing age worldwide, around 190 million people, are affected by endometriosis. The economic impact is significant, with costs exceeding 80 billion USD annually [1-4]. It manifests as a chronic ailment with symptoms that can be debilitating, such as severe menstrual pain, discomfort during sex, difficulties with bowel movements or urination, dysuria, ongoing pelvic pain, bloating, constipation, painful bowel movements, nausea, exhaustion, and in some cases, depression and anxiety [1,3,4]. Approximately 40-50% of women with infertility issues have endometriosis [3-5]. Although various mechanisms have been suggested to explain infertility linked to endometriosis, there is no conclusive evidence of its association with endometrial receptivity. A recent study found a slight decrease in live birth rates among women with a history of endometriosis, suggesting that minor impairments in uterine receptivity might contribute to infertility in these women [6].

On the other hand, the condition distorts pelvic anatomy, causes adhesions and fallopian tube scarring, and leads to local inflammation and hormonal regulation disruptions [3-5]. These symptoms can significantly affect a person’s quality of life, education, career, and relationships [1-5]. This article offers a comprehensive overview of the current understanding and recent advancements in the theories of endometriosis pathogenesis, with our opinion on the need for a few RCTs designed to confirm the pathogenesis. An extensive literature search was performed using databases such as PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, employing keywords including “endometriosis,” “pathogenesis,” “theory,” and “epidemiology.” The aim of synthesizing these findings is to provide a wide-ranging perspective on endometriosis pathogenesis, emphasizing potential areas for future research.

Endometriosis can present a wide range of symptoms that significantly impact the quality of life and emotional well-being, including pain, fatigue, heavy menstrual bleeding, and mood swings. These symptoms can affect education, career, and intimate relationships [1- 8]. The condition can start with the first menstrual period and continue in varying patterns until menopause. Starting menstruation after age 14 is significantly correlated with a lower risk of developing endometriosis. Currently, there is no known way to prevent the disease, and while it cannot be cured, symptoms can be managed through medication or surgery [4,9,10]. Endometriosis manifests in three main forms: superficial peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriomas, and deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) [1,2,4,10-12]. DIE penetrates organs in the pelvic area and often requires surgical treatment. The disease can progress in 37% of cases, remain stable in 50%, and regress in 17% (10). Surgery for DIE carries a risk of major complications (3-4%) and minor complications (10-15%) [12]. Gaining a full grasp of the complex processes behind endometriosis is essential for advancing treatment options, which are presently inadequate [2,5,12]. A recent large-scale, web-based survey revealed that women with endometriosis endure a lengthy and challenging journey before receiving a diagnosis and effective treatment, highlighting the urgent need to reduce diagnostic delays. On average, seven years elapse between the onset of symptoms (at 23.8 ± 10.2 years) and diagnosis (31.0 ± 8.9 years). Women reported an average of 4.6 ± 2.3 symptoms, with 82% experiencing severe pain (pain scores between 7 and 10). After diagnosis, 66% of women received medical treatment, primarily hormonal (45%), which significantly reduced pain intensity (VAS scores after treatment = 4.9 ± 2.7, p < 0.001). Additionally, 62% had undergone surgery, with 22% undergoing laparotomies. The survey highlighted significant impacts on daily life, particularly in sexual, psychological, and physical areas, with an overall quality of life score averaging 4.3 ± 2.6 out of 1013.

Developing new interventions to prevent both the occurrence and recurrence of endometriosis is crucial. The exact cause of endometriosis is not definitively known, but several theories offer insights into its potential origins and guide research toward innovative treatments [2,3,8,9,12]. These theories include metastatic dissemination, surgical transplantation, genetic factors, coelomic metaplasia, immune dysregulation, embryonic cell origin, endometrial stem cell involvement, hormonal imbalance, bone marrow stem cells, and retrograde menstruation [1-10]. Recent research also suggests the possible role of microbiota in the development of endometriosis, indicating that the role of infection in disease etiology should be further investigated14. Despite these theories, questions remain about why certain women are affected, the varied progression of the disease, and its resistance to progesterone treatment [1-8].

While the Sampson theory on endometriosis is supported by numerous facts [1-4,8,9], it seems to leave some questions unanswered. However, a careful, deep analysis can provide answers to these questions:

Variability in Affected Women

Endometriosis affects certain women and not others due to differences in the amount and frequency of endometrial debris transported through the fallopian tubes and subsequently implanted in the pelvic cavity (Figure 1) [1-4].

Disease Progression

The progression of endometriosis in some women, while remaining stable in others, is influenced by individual combinations of chemical- physical factors. These factors determine the capacity for leakage and accumulation of endometrial debris (Figures 1A-1C) [1-4,8,9].

Beyond Oversimplified Views

Viewing endometriosis as merely a chronic, inflammatory, multifaceted disease that resists progesterone treatment is an oversimplification. The Sampson theory emphasizes that the chronic nature, inflammation, and complexity of the disease result from the continued presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus [1-4,8,9].

Mechanical Aspects

Understanding the mechanical aspects of how endometriosis begins and advances is crucial. Detailed explanations are needed to guide the creation of targeted and effective treatments rather than relying on general theories [1-4,8,9]. Physical and chemical factors such as the size of the cervical canal, the dimensions of the tubal ostia, the configuration of the tubal portion within the uterine wall, the length of the tubes, the functioning of the junction between the uterus and tubes, the volume of menstrual flow, the personal placement of the uterus, the size of its openings, and the frequency and intensity of myometrial contractions significantly contribute to the likelihood of developing endometriosis (Figures 1A-1C) [1-4,8,9]. These factors particularly affect individuals with obstructive Müllerian anomalies 25. The principles laid out by Bernoulli, Torricelli, and Laplace [8,13,14] underpin the variation in quantities from person to person (Figures 1A-1C).

The retrograde menstruation theory (Sampson)15,16suggests that during menstruation, some endometrial tissue may backflow through the fallopian tubes into the abdominal cavity, potentially leading to the formation of endometriotic lesions [12,15-18] (Figures 1A-1C). Recurrent endometrial accumulation infiltrates deeper structures or appears outside the peritoneal cavity, where lymphatic dissemination has been implicated 2-9. Risk factors such as short menstrual cycles, extended menstrual periods, and uterine obstructions are associated with the development of the disease in women with open fallopian tubes 1-4

A - Endometrial Shedding

Debris exits through the cervix and tubes, with the tubes acting as filters. Uterine contractions and anatomy affect this process. The cumulative regurgitation of endometrial debris through the tubal opening into the pelvic cavity is governed by Bernoulli, Torricelli, and Laplace Laws, which is responsible for the progression and regression of the disease (Figure 1A). The individual length and internal size of cervical and tubal openings filter the endometrial debris from the lumen content to the pelvic cavity.

B - Uterine Position

Normoverted, Anteverted, and Retroverted. Different uterine positions influence the flow of endometrial debris through the cervix and tubes. This may explain the varying occurrences of endometriosis (Figure 1B).

C - Uterine Contractions

Contraction patterns influence the displacement of uterine content, with estrogen increasing and progesterone decreasing contraction frequency. This introduces three different patterns and related directions of displacement through the cervical os, tubal openings, or both (Figure 1C).

Endometriosis as a Systemic Disease?

Endometriosis is considered a systemic disease, evidenced by the presence of extra-pelvic endometriosis, including thoracic endometriosis. Retrograde menstruation is a potential mechanism but does not fully explain the disease’s pathophysiology [19]. There may be a genetically predisposed condition [20-23] that, when combined with retrograde menstruation, leads to endometriosis. Although most cases (>98%) are not hereditary, understanding disease risk according to subphenotypes could be promising. Retrograde menstruation is an intrinsic part of the overall predisposition, potentially influenced by abnormal myometrial contractions [4,10,24-26]. Adolescents with obstructive Müllerian anomalies are more prone to developing endometriosis and hematosalpinx [27]. Both endogenous and exogenous stem cells may also play a role, with bone marrow-derived stem cells potentially colonizing the endometrium [28,29]. Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory disease, and while chronic inflammation has long-term consequences, the pathogenesis may still be rooted in retrograde menstruation.

This condition allows blood and endometrial cells to pass through the fallopian tubes, causing persistent inflammation. Endometriosis has been linked to diseases such as atherosclerosis, migraines, and Raynaud’s syndrome, as well as a tendency towards a hypercoagulable state [30]. The inflammatory response affects cytokine cascade metabolites, increasing uterine contractions [13]. It remains unclear whether vascular endothelial damage [17] is a cause or consequence of the inflammation, and whether this is specific to endometriosis or common to general inflammation. Given these complexities, the question remains: how do we stop the disease? Should we slow down estrogen pressure or engage in radical surgeries, or can we engage in prevention? The inflammatory cells release cytokines and chemokines, causing further inflammation. Interestingly, progesterone acts not only as an antiproliferative agent but also as an immune modulator [31]. Chronic inflammation in endometriosis suggests it may also be an autoimmune disease. Traditional treatments often yield partial results. Interventions aimed at reversing key causal phenomena, such as retrograde menstruation, should be prioritized, alongside early diagnostic tools [32,33]. Preventing the retrograde transit of endometrial debris could reduce the disease’s incidence and complications. Sub-classifications of endometriosis that predict prognosis and enhance treatment prioritization are essential [32,33]. Recent studies identifying genetic alterations, such as APOBEC3B deletion, might help in better diagnosing and treating endometriosis [20].

Theoretical Framework

Retrograde menstruation can cause endometrial tissue to exit through the fallopian tubes [17,18,34] under specific conditions (Figures 1A-1C). Ovarian hormones and chronic inflammation promote the adhesion and growth of endometrial tissue in the pelvic cavity [1- 4,7], where undifferentiated mesenchymal cells in the peritoneum act as progenitors of endometrial stromal cells.

Supporting Evidence

Recurrent menstrual cycles exacerbate inflammation and tissue damage, progressing endometriosis [1-4,8,9]. Genetic, hormonal, lifestyle [35], and environmental factors contribute to the disease. Endometrial ablation and levonorgestrel IUDs can reduce recurrence and alleviate pain [8,9]. Postpartum cervical changes in parous women decrease endometriosis risk by promoting cervical outflow [14]. Reduced periods of amenorrhea, due to fewer pregnancies and less frequent breastfeeding in modern times, may increase the risk of endometriosis and adenomyosis among young women.

Interpretation of Facts

Normally, inflammation from menstruation is temporary and non-damaging. However, repeated menstrual cycles may lead to ongoing inflammation [1,5] increased production of utero-contracted prostaglandins, sequential increases in tubal debris outflow [17,18,27,28] and scarring, potentially contributing to conditions like adenomyosis.

Comparison with Existing Literature

Recurrent menstrual cycles cause repeated stress on the uterine lining and may result in basal endometrium fragments being dislodged into the pelvic area [1-8] and myometrium. This could lead to damage from excess iron and resistance to cell death40, promoting lesion progression and fibrosis.

Despite the acceptance of this pathophysiological hypothesis, specific randomized studies are lacking and therefore it remains the hypothesis with the highest presumption of correspondence to the real pathophysiology of its genesis but not yet included in the evidence.

Over a century since the initial pathogenetic hypothesis of endometriosis, the disease remains a significant challenge, affecting millions of women without a definitive cure. Despite numerous treatment strategies, the scientific community is at an impasse, partly due to the hesitation to invest in and validate the most credible theories. This hesitation has hindered progress in developing effective treatments.

Symptom Variability and Impact

Endometriosis significantly impairs quality of life, causing symptoms such as pain, fatigue, heavy bleeding, and emotional distress. These symptoms can start from the first menstrual period and continue until menopause, impacting education, career, and personal relationships. Women who begin menstruating after age 14 have a lower risk of developing endometriosis.

Types and Progression

There are three main types of endometriosis: superficial peritoneal, ovarian endometriomas, and deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE). DIE often invades pelvic organs and typically requires surgical intervention. Endometriosis can progress in 37% of cases, remain stable in 50%, and regress in 17%. Surgery for DIE carries a 3-4% risk of major complications.

Diagnostic Challenges

Women with endometriosis often face long delays in diagnosis and treatment, averaging seven years from symptom onset to diagnosis. Common symptoms include severe pain, with 82% of women reporting pain scores between 7 and 10. Post-diagnosis, 66% receive hormonal treatment, significantly reducing pain, and 62% undergo surgery.

Need for New Interventions

New interventions are urgently needed to prevent the occurrence and recurrence of endometriosis.

Theories of Origin

The exact cause of endometriosis remains unknown. Theories include metastatic dissemination, genetic factors, coelomic metaplasia, immune dysregulation, embryonic cell origin, involvement of endometrial stem cells, hormonal imbalance, and retrograde menstruation. Recent research suggests a potential role for microbiota in disease development.

Sampson Theory and Unanswered Questions

While the Sampson theory of retrograde menstruation explains some aspects of endometriosis, it leaves several questions unanswered, such as why some women develop the disease and others do not, and why the disease progresses in some cases but not others. This variability may be due to differences in the amount and frequency of endometrial debris transported through the fallopian tubes and individual biochemical and biophysical factors [36-38].

Mechanical and Chemical Influences

Factors such as the size of the cervical canal, the dimensions of the tubal ostia, the configuration of the tubal portion within the uterine wall, menstrual flow volume, uterine placement, and myometrial contractions significantly influence the development of endometriosis. These factors affect the volume of blood and endometrial cells regurgitate each cycle, contributing to the likelihood of developing the disease.

Genetic and Mechanical Contributions

Genetic predisposition and physical dynamics (such as principles of Bernoulli, Torricelli, and Laplace) explain variations in disease prevalence among individuals, especially those with obstructive Müllerian anomalies. While retrograde menstruation is common, not all women develop endometriosis or adenomyosis, suggesting protective mechanisms are at play. Variations in the amount of endometrial debris, its passage through the cervix or fallopian tubes, uterine contractions, and the filtering ability of the tubes could explain discrepancies in disease development (Figures 1A-1C).

Future Directions

New strategies for prevention and relapse should include hormonal changes, biochemical agents affecting uterine muscle movements, introducing uterine pacemakers [31,39] and altering retrograde menstruation to flow through the cervical opening, potentially by enlarging its internal uterine opening [17]. Retrograde menstruation, stem cells, embryologic remnants, and/or metastases could occur in all women, yet endometriosis does not develop universally. Therefore, we need precise mechanistic explanations rather than simplistic “just-so” stories to understand why and how the disease begins and progresses, to identify effective therapeutic interventions. To achieve this goal, we must step out of our “comfort zone” and avoid complacency [36-38,40]. We require fundamental changes in our interpretation of clinical, imaging, surgical, and pathological data. In our opinion, if we do not alter our conceptualization of the disease, accumulating more data, regardless of how it is obtained, will contribute little to our understanding. We must embark on a path of treatment experimentation based on the most credible pathogenetic theory after 100 years. This is essential to prevent the onset, progression, and recurrence of the disease. This path is now obligatory [41,42] (Table 1).

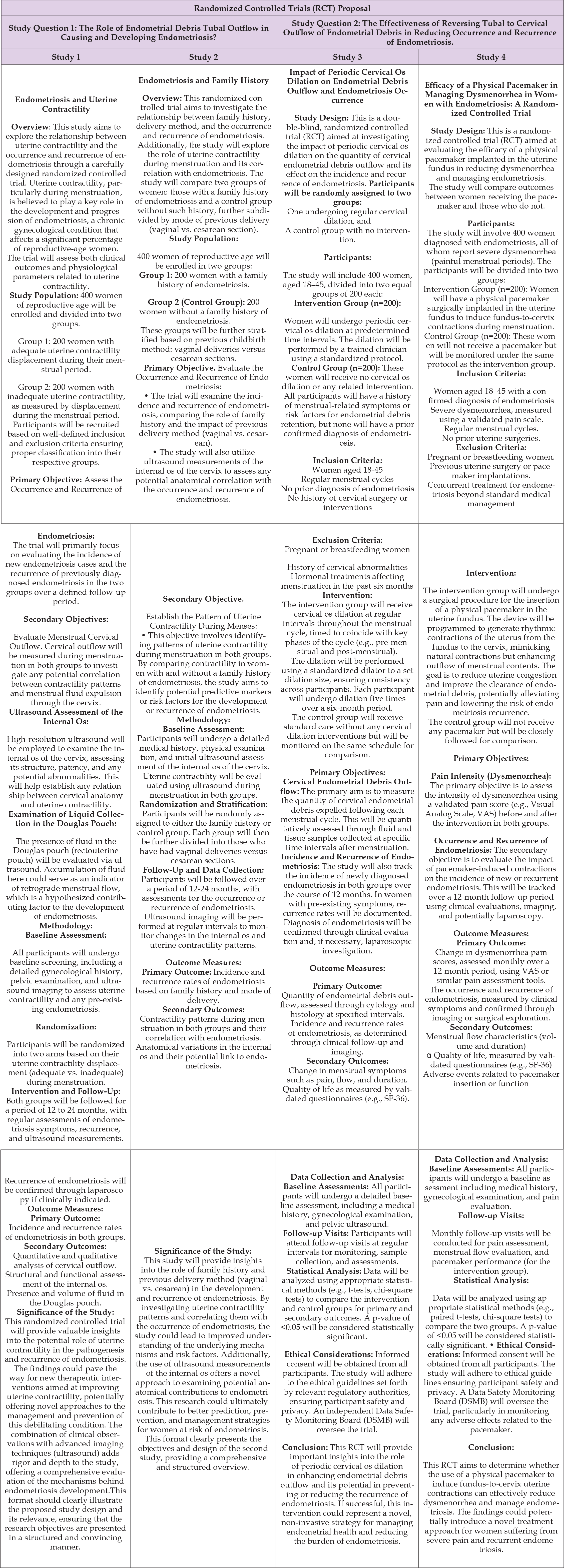

Table 1: The table reports the proposal of 4 RCTs aimed at strengthening the pathogenic hypothesis of endometriosis with more robust evidence that lays the foundation for treatments consistent with this physiopathology. Two of the four studies establish two potential intervention tools that are the result of this hypothesis.

• Francesco Maria Bulletti and Carlo Bulletti contributed

equally to this article in terms of conceptualization and the

first draft of the manuscript. Francesco Maria Bulletti wrote

the last version of the manuscript

• Antonio Palagiano and Maurizio Guido provided to search

and first selection of the studies required and remarked the

more realistic pathogenetic concept reported

• Maria Elisabetta Coccia revised the second and third draft

• Ethical Considerations are not applicable.