Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Melese Tadesse Aredo1*, Abebe Ferede1, Gizachew Abdeta1, Addis Wordofa Tekle1, Abduselam Shemsedin2, Biniyam Zemedkun2, Haile Tamirat2, Hanna Feleke2, Kalkidan Korenti2 and Lidya Wondimu2

Received: August 29, 2024; Published: September 16,2024

*Corresponding author: Melese Tadesse, Arsi University College of Health Science, Department of Public Health Asella city, Ethiopia

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.58.009187

Introduction: Exclusive breastfeeding is a highly effective and cost-efficient intervention for preventing childhood morbidities and mortalities. It can prevent approximately 13% of childhood deaths, which equates to saving at least 1.2 million children worldwide each year. However, globally, only about 35% of infants are exclusively breastfed. In developing countries, the rate is 38% for infants under six months, while in Ethiopia, approximately 52% of infants in this age group are exclusively breastfed.

Objective: This study aims to assess the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding practices and identify the associated factors among mothers of infants under six months old who are attending the pediatric outpatient department (OPD) and immunization clinics (EPI) at ARTH.

Methodology: An institutional-based cross-sectional study design was employed. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire administered by six graduating Public Health students from Asella Health Science College, who received a two-day training. The collected data were coded, cleaned, and entered into Epi Info, then exported to SPSS version 26 for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to present the respondents’ characteristics through frequencies, percentages, summary measures, tables, and graphs. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to identify factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding, using odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. A significance level was set at a p-value < 0.05.

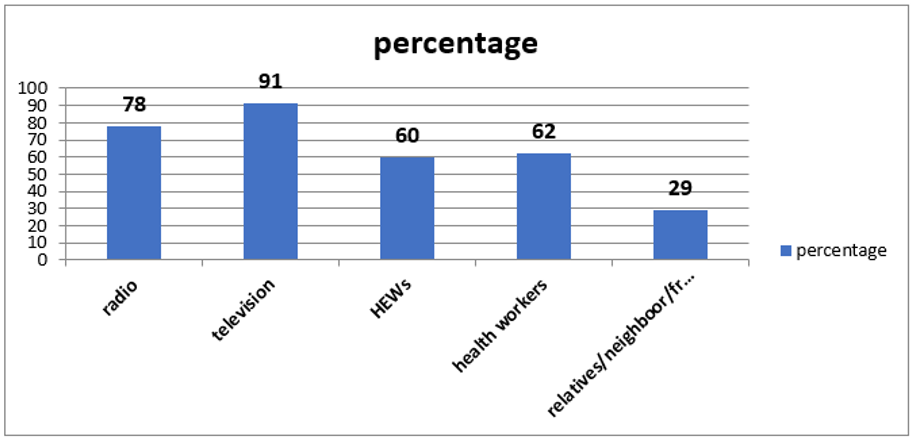

Result: Around (40.4%) of mothers Out of 384 eligible mothers, all 384 agreed to participate in the study, resulting in a response rate of 100%. Approximately one-third (36.2%) of the mothers were aged between 25 and 29 years. Regarding the reasons mothers cited for not breastfeeding, 36.5% reported that they believed breast milk was insufficient, 13% mentioned that the infant was thirsty, and 8% cited a lack of time. Among the various socio-demographic, health service, maternal, and infant-related factors assessed, several determinants were identified for higher chances of EBF practice. These Factors Include:

Age of The Infant: Younger infants (0-3 months) are more likely to be exclusively breastfed compared to older infants (4-5 months).

Maternal occupation: Unemployed mothers are more likely to practice EBF than employed mothers.

Household Income: Mothers with lower monthly incomes are more likely to practice EBF.

Conclusion and Recommendation: The study revealed a high participation rate of 100% among the 384 eligible mothers, with a significant portion (36.2%) aged between 25 and 29 years. Despite the positive response, barriers to breastfeeding were identified, with 36.5% of mothers believing that breast milk was insufficient, 13% indicating their infants were thirsty, and 8% citing time constraints as reasons for not breastfeeding. Several sociodemographic and health-related factors significantly influence the practice of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF). Younger infants (0-3 months) are more likely to be exclusively breastfed compared to those aged 4-5 months. Additionally, unemployed mothers and those with lower household incomes demonstrate higher rates of EBF practice.

Recommendations:

1. Education and Support: Implement educational programs aimed at addressing misconceptions about breast milk sufficiency and providing practical support for breastfeeding mothers, especially those returning to work.

2. Targeted Interventions: Focus on supporting employed mothers with resources and strategies to facilitate EBF, such as flexible work policies and access to breastfeeding-friendly environments.

3. Income-Based Initiatives: Develop targeted initiatives to support lower-income families in their breastfeeding efforts, ensuring access to necessary resources and information.

Keywords: Exclusive Breast Feeding; Hospital; Ethiopia

Abbreviations: EBF: Exclusive Breastfeeding; ARTH: Asella Referral and Teaching Hospital; OPD: Pediatric Outpatient Department; IHRERC: Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee; ANC: Antenatal Care; PNC: Postnatal Care

Exclusive breastfeeding refers to feeding an infant with breast milk from his or her mother or a wet nurse, or expressed breast milk without any additional solid or liquid foods, except for oral rehydration salt, syrups of vitamins, minerals and medicines [1]. Babies who are breastfed exclusively for 6 months experience less illnesses because breast milk contains nutrients and substances that protect the baby from several infections, some chronic disease and it leads to improved cognitive development [2]. Gastroenteritis, or the family of digestive diseases whose primary symptom is diarrhea, occurs less often among exclusively breastfed children and is less severe when it does occur [3]. One and half million infants’ death can be avoided each year by exclusive breastfeeding. Children who are exclusively breastfed have protection from several acute and chronic diseases such as, otitis media, respiratory tract infections, atopic dermatitis, gastroenteritis, type 2 diabetes, sudden infant death syndrome, obesity and asthma during childhood [4]. A large global disease burden is attributed to sub-optimal breastfeeding accounting for 77% and 85% of the under -five deaths and disability adjusted life years (DALYs), respectively. [5], Sub-optimal breastfeeding especially non-exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life, results in 1.4 million deaths and 10% of disease burden occurs in children younger than 5 years [6]. Most of the infant deaths in the first year of life are largely associated with inappropriate feeding practices.

It is estimated that over 7 million children under the age of five die each year in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia and the major contributor to most of the infant death is poor feeding practices. In Ghana, there is evidence that 40% of all deaths that occur in the country before age five are related to malnutrition (severe and moderate malnutrition) [7,8]. Only 35% of infants world-wide are exclusively breastfed during the first four months of life and complementary feeding begins either too early or too late with foods which are often nutritionally inadequate and unsafe [9]. Therefore Improving exclusive breastfeeding rates among the poorest may be particularly important in the reduction of global disparities in child survival and health [10]. Sub-Saharan Africa has the poorest child health record, accounting for over half of all deaths of children worldwide. The most common causes of mortality are pneumonia and diarrhea, together accounting for over 30% of child death, but these diseases may partially be prevented by exclusive breastfeeding. Exclusive Breastfeeding promotion has been identified as one of the interventions with the highest lifesaving potential globally, and if all children were optimally breastfed, this could potentially save 13% of child deaths worldwide [11]. In Ethiopia, malnutrition is the major cause of child mortality. Almost 70% of infants were reported to be sub-optimally breastfed and 24% of deaths among infants were attributed to poor and inappropriate breastfeeding practice.

According to 2011 EDHS, 59% of infants were exclusively breastfeed for the first six months after birth. 29% of newborns received pre-lacteal feed and 69.1% of them were put to breast within one hour [12]. Although breastfeeding is common in Ethiopia large number of mothers, do not practice appropriate breastfeeding and complementary feeding recommendations. These are largely due to lack of knowledge of how to feed properly and food insecurity. A recent report revealed that 27% of mother’s early offer water, butter and various types of food to nourish their children, thus reducing the percentage of exclusively breastfeed and increasing the percentage of receiving complementary food at very young age [13]. A community based Analytical cross-sectional study conducted in East Ethiopia showed that the rate of non-exclusive breast feeding in infants aged under six months was 28.3 %. [14]. To improve exclusive breastfeeding, factors influencing its practice have to be identified in order to target these in program implementation. In East Arsi the determinants of exclusive breastfeeding especially in resource poor settings have not been fully assessed. This study therefore will obtain information which would lead to a better understanding of the prevalence and factors influencing exclusive breastfeeding practice in this area based on data obtained from mothers of infants under six months attending pediatrics OPD and EPI in ARTH.

The study was conducted at Asella Referral and Teaching Hospital (ARTH), located in Asella Town, East Arsi Zone, Oromia Region. Asella is situated 149 km southeast of Addis Ababa and 75 km north of Adama, at an elevation of 2,430 meters above sea level. According to the 2007 national census, Asella Town has a total population of 67,269, with 33,443 of these being women. In terms of healthcare infrastructure, the town is equipped with two governmental health centers, one referral teaching hospital, 14 private health institutions, and 2 non-governmental health institutions. Asella Referral and Teaching Hospital, established in 1964 through an Ethio-Italian collaboration, currently serves as a referral facility for approximately 3.5 million people in the Arsi Zone. The hospital employs 139 medical doctors, 39 laboratory technicians, 43 midwives, 199 nurses, and 32 pharmacy staff members. The study was carried out from January 14 to January 21.

Institutional based cross-sectional study design was used.

Source Population: The source population for this study comprises all mothers of infants aged under six months who reside in the catchment area of Asella Referral and Teaching Hospital (ARTH).

Study Population: The study population includes all mothers of infants aged under six months who are attending the pediatric outpatient department (OPD) and immunization clinics (EPI) at Asella Referral and Teaching Hospital (ARTH).

Sample Population: The study population consists of all selected mothers of infants aged under six months who attended Asella Referral and Teaching Hospital (ARTH) during the study period.

Inclusion Criteria

• Mothers with infants aged under six months

• Mothers who attended the pediatric outpatient department (OPD) and immunization clinics (EPI) at Asella Referral and Teaching Hospital (ARTH) during the study period.

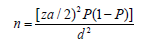

Sample Size Determination: The sample size (n) required for the study was calculated using the formula to estimate a single population proportion.

Where n= required sample size

Za/2= standard normal distribution taken as 1.96 at 95% confident level.

P= 49.4% (from study done in southern Ethiopia, Hadiya on non-exclusive breast feeding in).

d= margin of error 5%

10% non- response rate will be considered.

Sampling Technique: Non-probability convenience method was used.

Dependent Variable:

• Non-Exclusive breastfeeding practice.

Independent Variables:

The independent variables include

1. Parental socio economic and demographic characteristics:

• Age of the mother

• Marital status of the mother

• Education level of the mother

• Occupation of the mother

• Educational status of father

• Husband occupation

• Husband support

• Cultural support

• Religious support

• Average household monthly income

2. Maternal Health and Health Care Service Utilization

• Maternal morbidity status,

• Maternal knowledge on exclusive breastfeeding practices,

• Maternal attitude on EBF practice

• ANC follow up status

• PNC follow up status

• Place of delivery,

3. Infant characteristic:

• Infant age in completed months,

• Infant sex.

• Infant morbidity status

• Colostrums feeding status

• Pre- lacteal feeding status

• Birth interval

• Birth order

Non-Exclusive Breastfeeding: This means when study subjects in the age range of 0-5 fed other foods or fluids other than medicine, oral rehydration, drops or syrups (vitamins and syrups) in addition to breast milk 24 hours prior to the Survey (WHO,2008).

Maternal Knowledge About EBF: Mothers is said to be knowledgeable if she answers more than 50% questions about knowledge on exclusive breastfeeding.

Maternal Attitude About EBF: Mothers have a positive attitude if she answers more than 50% questions about attitude on exclusive breastfeeding.

The study was conducted over a period of one week. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire, originally prepared in English and subsequently translated into the local languages (Amharic and Afaan-Oromo). Six graduating public health students participated in data collection. These data collectors received a two-day training session, which covered questionnaire administration, interviewing techniques, and standardizing the method of asking questions in the local languages.

The questionnaire was translated into the local languages (Amharic and Afaan-Oromo) for data collection and retranslated back into English to ensure consistency. Data collectors were trained on the use of the questionnaire and the data collection procedures, and they were closely supervised by the principal investigator. To ensure the validity of the instrument, the questionnaire pretested 5% of the total sample size outside the study area. Confidentiality of the respondents was assured throughout the study. The completeness of the questionnaires was checked daily by the principal investigator, and data entry was performed by two data clerks. Finally, multivariate analysis was conducted to control confounding factors.

The collected data was coded, cleaned, and entered Epi Info, then exported to SPSS version 26 for analysis. Descriptive statistics were analyzed and presented using frequencies, percentages, summary measures, tables, and graphs. Bivariate analysis was performed to assess associations between independent and dependent variables by computing crude odds ratios. Subsequently, multivariate analysis was conducted to identify factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding by calculating adjusted odds ratios. Statistical significance was determined at a p-value < 0.05.

This research received approval from the Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee (IHRERC). An official letter requesting cooperation was issued by the School of Health Sciences to Asella Referral and Teaching Hospital (ARTH). Permission to collect data was obtained from the Administrator of ARTH, the Head of the Health Office, and the Kebele leader (the lowest administrative level). Informed consent, either written or via thumbprint, was required from respondents selected to participate in the study. Data collectors informed respondents about the purpose of the study and assured them that their information would be kept confidential and used solely for research purposes. Additionally, verbal consent was obtained from each respondent.

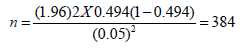

Out of 384 eligible mothers, 384 agreed to participate in this study, which made a responserate of 100%. Around one third (36.2%) of mothers were between 25-29 years. Around (40.4%) of mothers Out of 384 eligible mothers, all 384 agreed to participate in the study, resulting in a response rate of 100%. Approximately one-third (36.2%) of the mothers were aged between 25 and 29 years. Around 40.4% of the mothers identified as Orthodox Christians. In terms of educational status, 144 mothers (37.5%) had attended primary education. The majority (81.3%) of the study participants were unemployed. were Orthodox Christian. Regarding educational status, 144(37.5%) mothers attended primary education. The majority (81.3%) of study participants were unemployed mothers (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of mothers (respondents) who have infants less than sixmonths old, attending pediatrics OPD and EPI in ARTH, Asella, East Arsi, Ethiopia, 2022.

Note: Others* 1Catholic and Wakefeta.*others 2 Gurage and Siltte.

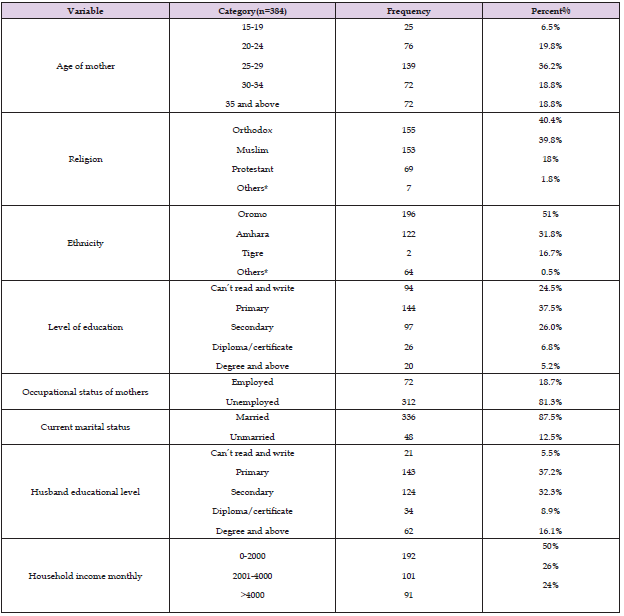

Almost half (52.8%) of the mothers had 2 to 3 children. Among the infants, 222 (57.8%) were between 4 and 5 months old, and 110 infants (28.4%) were second in birth order. Most mothers (85.4%) received antenatal care (ANC). Regarding the place of delivery, most mothers (86.2%) delivered in a health institution. Additionally, approximately 80.2% of mothers received postnatal care, and 154 mothers (63.1%) were informed about the importance of exclusive breastfeeding for up to six months (Table 2).

Table 2: Maternity and Infant/maternal health service utilization characteristics of study participants who have infants less than six months old, attending pediatrics OPD and EPI in ARTH, Asella, East Arsi zone, Ethiopia, 2022.

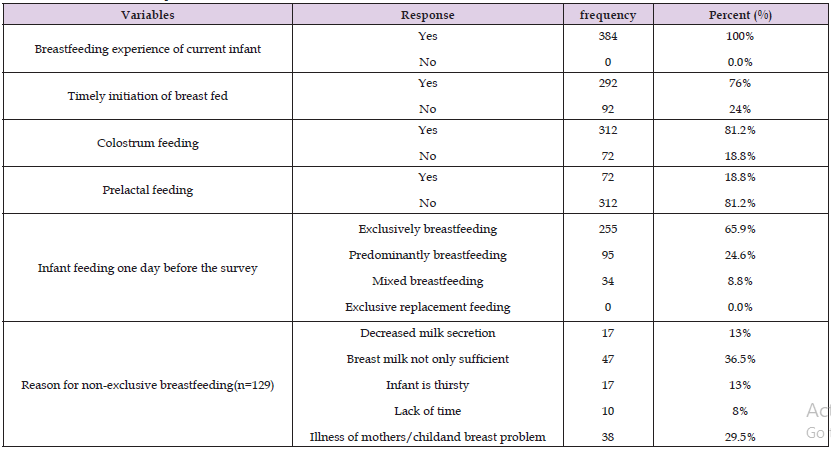

All mothers were breastfeeding their infants at the time of the study. Of these, 320 mothers (76.0%) initiated breastfeeding within one hour of birth. Most mothers (81.2%) fed colostrum (the first milk) to their newborns. Additionally, 81.2% of mothers did not give any prelacteal foods other than breast milk within the first three days of their infants’ lives. The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding one day before the survey was 65.9%. Among the mothers who did not exclusively breastfeed, the main reasons cited were the perception that breast milk alone was insufficient (47 mothers, 36.5%), illness of the child or mother (38 mothers, 29.5%), and decreased breast milk secretion (17 mothers, 13.0%) (Table 3). Regarding the reasons mothers cited for not breastfeeding, 36.5% reported that they believed breast milk was insufficient, 13% mentioned that the infant was thirsty, and 8% cited a lack of time (Figure 1).

Table 3: Breastfeeding related practices of mothers who have infants less than six months old, attending pediatrics OPD and EPI in ARTH, Asella, East Arsi zone, Ethiopia, 2022.

Figure 1: Reasons for mothers not to breastfeed their infants attending pediatrics OPD and EPI in ARTH, Asella, East Arsi zone, Ethiopia, 2022.

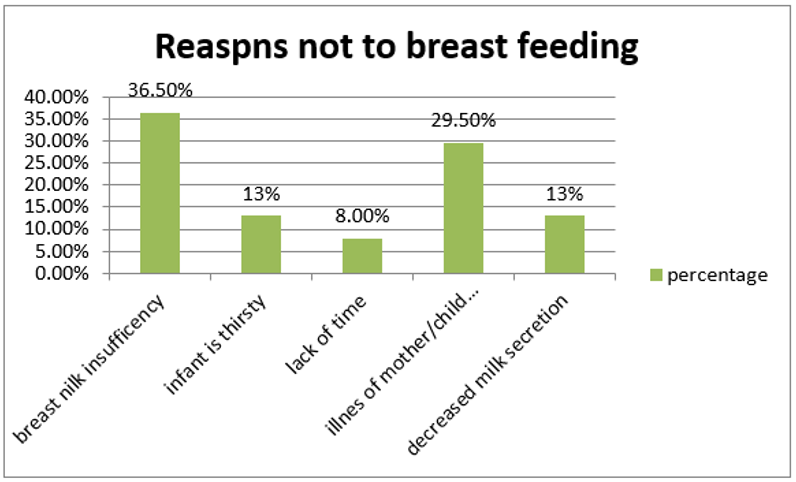

Regarding the source of information about exclusive breastfeeding, 362 mothers (89.4%) obtained their information from various sources (Figure 2).

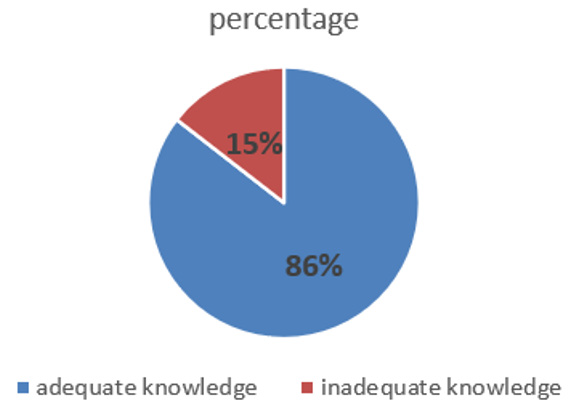

Knowledge of Mothers Regarding to Breastfeeding: Almost two-thirds (75.8%) of mothers understand that breast milk alone, without water or other liquids, is sufficient for an infant during the first six months of life. Breast-feeding knowledge was evaluated through a series of questions. Mothers who answered half or more of the questions correctly were classified as having adequate knowledge about breastfeeding. In contrast, mothers who answered fewer than half of the questions correctly were classified as having inadequate knowledge about breastfeeding (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Sources of information for mothers about EBF who have infant less than six months old attending pediatrics OPD and EPI in ARTH, Asella, East Arsi zone, Ethiopia, 2022.

Figure 3: Percent distribution of level of Knowledge on breastfeeding of mothers who have infantless than six months old attending pediatrics OPD and EPI in ARTH, Asella, East Arsi zone, Ethiopia, 2022.

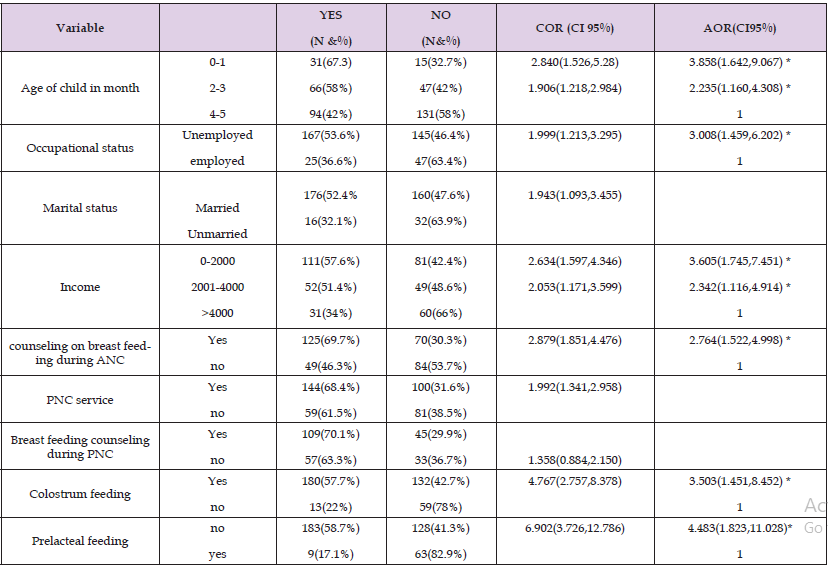

Out of the total participants in this study, 65.9% of mothers practiced exclusive breastfeeding. To identify factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding, each variable was initially assessed independently to determine its potential as a predictor. Bivariate analysis was conducted to identify variables associated with exclusive breastfeeding (p < 0.05). The variables found to be associated included the age of the infant, maternal occupation, marital status, household income, breastfeeding counseling during antenatal care (ANC), postnatal care (PNC), and breastfeeding counseling during PNC, prelacteal feeding, and colostrum feeding. These variables were then tested in a multivariate analysis to determine their significant associations with exclusive breastfeeding practice. After adjusting for potential confounders in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the following factors remained significant in the final model: age of the infant, maternal occupation, household income, breastfeeding counseling during ANC, colostrum feeding, and prelacteal feeding. Marital status, PNC service, and breastfeeding counseling during PNC were not significant in the final model (Table 4).

Table 4: Factors that affect EBF practice among mothers of infants age less than 6 months using bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis model, East Arsi, Ethiopia, 2022.

Breast milk is the only natural, complete, and complex nutrition for human infants. It surpasses any other product given to a baby as it is immediately available, fresh, at the correct temperature, and economical. Breast milk meets all of an infant’s nutritional and fluid needs in the first six months, providing an ideal combination of proteins, fats, carbohydrates, and fluids. Exclusive breastfeeding is recommended for infants during the first six months of life. Exclusively breastfed children are at significantly lower risk of infection and benefit from a cost-effective intervention that reduces infant morbidity and mortality. Despite the known benefits of exclusive breastfeeding, the practice remains suboptimal in the study area. Only 65.9% of mothers reported exclusively breastfeeding their infants, which is below the Ethiopian Health Sector Development Plan IV (HSDP IV) target to increase the proportion of exclusively breastfeeding mothers from 49% to 70% by the end of 2015 [15]. This finding is similar to studies conducted in Goba District (71.3%) [16], Jimma Town (67.2%) [17], Madagascar (68%) [18], and Brazil (72.5%) [19]. However, it is lower than the rates reported in Ghana (79%) [20] and Iran (82%) [21], which may be attributed to the smaller sample sizes in those studies, potentially leading to higher estimates of exclusive breastfeeding rates. In contrast, the rate in this study is higher than those reported in Bahir Dar City Administration (50.36%) [22], the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) 2019 (59%) [23], Bolivia (65%) [24], Turkey (50.6%) [25], the UK (35%) [26], and Canada (13.8%) [27].

This variation may be due to increased accessibility to information in recent times, which could enhance the mother-infant bond and subsequently boost breastfeeding rates. The main reasons cited by mothers for discontinuing exclusive breastfeeding early were: perception that breast milk alone was insufficient for infants (47 mothers, 36.25%), lack of time (10 mothers, 8.0%), decreased breast milk secretion (17 mothers, 13.0%), perception that the infant was thirsty (17 mothers, 13.0%), and breast problems or maternal illness (38 mothers, 29.5%). These findings are consistent with studies conducted in South Africa [28] and Awi Zone, Ethiopia [29]. The predominant factor influencing the practice of exclusive breastfeeding was mothers’ perception that breast milk alone was not sufficient for their infants. Addressing these misconceptions through targeted education and counseling is crucial. Emphasizing the importance and adequacy of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life can help reverse these incorrect beliefs and improve breastfeeding practices. Among the various socio-demographic factors assessed, maternal occupation was significantly associated with exclusive breastfeeding practice. Unemployed mothers were three times more likely to practice exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) compared to employed mothers. This finding is consistent with studies conducted in Malaysia [30], Ghana [20], Awi Zone, Ethiopia [29], and Debre Markos, Ethiopia [31].

This association may be due to the limited duration of maternity leave for employed mothers, who often return to work within a few months of their infant’s life. Employed mothers face several challenges that hinder their ability to exclusively breastfeed, including lack of time, the distance between their workplace and home, inadequate private space for breastfeeding or expressing milk at work, inflexible work schedules, and the absence of on-site or nearby childcare centers. Additional factors such as weaning in preparation for returning to work, maternal exhaustion, and the challenge of balancing work and breastfeeding further complicate the situation. Moreover, employed mothers often have higher incomes compared to unemployed mothers, which may lead to increased use of alternative feeding options, such as formula milk. The aggressive promotion of infant formula, which is more accessible to employed mothers through various media, may also contribute to the lower rates of EBF among working mothers. In this study, household income was significantly associated with exclusive breastfeeding. Mothers with a monthly income of less than 2000 birr were 3.6 times more likely to practice exclusive breastfeeding compared to those with a monthly household income of 2001 birr and above.

This may be because mothers with lower incomes have fewer resources to purchase alternative foods, making exclusive breastfeeding a more viable option. Additionally, many of these lower-income mothers were unemployed, which allowed them more time to exclusively breastfeed. However, this finding contrasts with studies conducted in Bangladesh [32] and a study using EDHS 2019 data in Ethiopia [23]. The differences may be attributed to various factors, including sociocultural, economic, and health-related differences, such as variations in income and employment status across countries. In the Ethiopian study using EDHS data, income was assessed using a wealth index rather than average monthly household income, which could account for the discrepancy in findings. Among infant-related factors, the age of the infant was significantly associated with exclusive breastfeeding practice. Infants aged 0-1 month were four times more likely to be exclusively breastfed compared to infants aged 4-5 months. Similarly, infants aged 2-3 months were nearly twice as likely to be exclusively breastfed as those aged 4-5 months. These findings are consistent with the 2011 EDHS report [33] and studies conducted in Brazil [19]. This association may be attributed to cultural practices that favor the early introduction of other liquids and foods.

There is a common misconception among mothers that as infants grow older, breast milk alone is insufficient, and that the infant becomes thirsty if only breastfed. Additionally, most postpartum care occurs during the first few months of an infant’s life, a period when mothers, particularly those who are employed and stay at home for up to two months, are more likely to exclusively breastfeed due to spending more time at home. Despite the fact that most mothers had antenatal follow-up during their pregnancy, some did not receive counseling about breastfeeding. Mothers who were counseled during pregnancy about breastfeeding were three times more likely to practice exclusive breastfeeding compared to those who were not counseled. This finding is consistent with studies conducted in low-income Latin American countries [34], Nigeria [35], and Debre Markos, Ethiopia [31]. This association may be attributed to supportive policies on maternal and child health, the presence of breastfeeding guidelines, and the training of health workers in infant feeding practices. Such training enhances health workers’ knowledge and skills in breastfeeding counseling, which in turn improves mothers’ understanding and appreciation of the demands and benefits of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF). Mothers who received counseling during pregnancy were better prepared both psychologically and economically to commit to exclusive breastfeeding.

Mothers who fed colostrum to their newborns were 3.5 times more likely to practice exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) compared to those who did not feed colostrum. This finding is consistent with studies conducted in Axum [36] and Dabat, Gonder [37]. In contrast, mothers who did not give prelacteal foods to their infants were nearly four times more likely to practice EBF than those who introduced prelacteal foods. This result aligns with findings from Saudi Arabia [38] and Debre Markos, Ethiopia [31]. The introduction of other foods before breastfeeding can reduce the infant’s suckling activity, which in turn decreases maternal milk secretion due to reduced breast stimulation. This often leads to the mother resorting to alternative foods. Conversely, feeding colostrum, which is rich in nutrients and antibodies, supports exclusive breastfeeding by ensuring that the infant receives the full benefits of breast milk from the start.

The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) in the study area was 65.9%, indicating that 34.1% of infants were not exclusively breastfed. This rate is lower than the value used for sample size calculation. Among the various socio-demographic, health service, maternal, and infant-related factors assessed, several determinants were identified for higher chances of EBF practice. These factors include:

Age of the Infant: Younger infants (0-3 months) are more likely to be exclusively breastfed compared to older infants (4-5 months).

Maternal Occupation: Unemployed mothers are more likely to practice EBF than employed mothers.

Household Income: Mothers with lower monthly incomes are more likely to practice EBF.

Breastfeeding counseling during antenatal care (ANC): Mothers who received counseling about breastfeeding during pregnancy are more likely to exclusively breastfeed.

Colostrum Feeding: Mothers who fed colostrum to their newborns are more likely to practice EBF.

Avoidance of prelacteal feeding: Mothers who did not give prelacteal foods are more likely to practice EBF. These findings underscore the importance of targeted interventions and support systems to promote exclusive breastfeeding, especially focusing on education and counseling, addressing economic and occupational factors, and encouraging the avoidance of prelacteal feeding practices.

This research was approved by Institutional Review Board of Arsi University College of Health Sciences

This section is not applicable because the research does not include individuals’ images or videos.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

There is no funder for this research work except for data collection which was funded by Oromia health bureau.

First and foremost, we would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to the Almighty God. We extend our sincere appreciation to Arsi University College of Health Science, Department of Public Health, for providing us with the opportunity to conduct this studies. Our deepest thanks go to our colleagues and family, for their intensive guidance, invaluable feedback, and support in completing this research.