Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Usiobeigbe OS*1, Airhomwanbor KO1, Omolumen LE1, Iyevhobu KO2, Obohwemu KO3, Idehen IC4, Asibor E5, Yakpir MG3, Ogedegbe A5, Koretaine S3, Echekwube ME5, Owusuaa-Asante MA3, Oboh MM6, Olawuyi MO7, Kennedy-Oberhiri IV8, Soyobi VY9 and Ajani DE10

Received: September 09, 2024; Published: September 16, 2024

*Corresponding author: Usiobeigbe OS, Department of Chemical Pathology, Faculty of Medical Laboratory Science, Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.58.009184

Background: Chronic kidney disease (CKD) remains a significant global health challenge. Traditional African

medicinal practices endorse Persea americana (avocado) leaf extracts to mitigate acetaminophen-induced

kidney damage. This study aimed to explore the effects of avocado leaf extracts on renal function tests in male

Wistar rats with acetaminophen-induced testicular injury and assess their potential therapeutic relevance in

CKD management.

Method: This experimental study involved 42 adult male Wistar rats divided into 7 groups and administered

varied treatments. Across different groups, animals were given water and food alongside varying doses of

acetaminophen, avocado extract, and a standard drug, adjusted to their individual body weights, ranging from

3000 mg/kg of acetaminophen alone to combinations including 100mg, 200mg, and 300mg of avocado extract

and 140 mg/kg of the standard drug. Post-treatment, blood samples were collected to assess renal markers,

including urea, creatine, and electrolyte levels.

Results: The findings revealed a robust positive correlation between the parameters at both the 5% level of

significance (p-value < 0.05) and the 10% level of significance (p-value < 0.1). Potassium exhibits statistical

significance at the 10% level (p-value: 0.076), but not at the more stringent 5% level, indicating that the null

hypothesis is not rejected at the 5% significance level. Sodium, with (p-value 0.077), is statistically significant at

the 10% level, but its significance slightly diminishes at the 5% level. Thus, the null hypothesis is not rejected at

the 5% significance level. Chloride, with (p-value of 0.208), is not statistically significant at either the 10% or 5%

significance levels, and consequently, the null hypothesis is not rejected at these levels. While potassium exhibits

statistical significance at the 10% level, sodium and chloride show diminished significance levels.

Conclusion: The findings revealed a statistically significant effect between acetaminophen-induced kidney damage

in male Wistar rats and the potential ameliorative effects of avocado leaves extract. Consequently, it was observed that

acetaminophen induces renal damage in male Wistar rats, and all the parameters employed in this study exhibited varying

degrees of significance. This implies that avocado leaves extract on acetaminophen-induced damage has a robust positive

effect on kidney damage in male Wistar rats. This nuanced result emphasizes the differential effects of avocado leaves on

individual electrolytes in restoring renal function compromised by toxicity.

Keywords: Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD); Persea Americana; Acetaminophen; Avocado; Wistar Ra

Avocado is a tropical native American fruit. It belongs to the Lauraceae family (Yasir, et al. [1]). The name ‘Avocado’ has been derived from the Aztec word ‘ahucatl’. ‘Alligator pear’ and ‘butter fruit’ are its’ alternative names. It has been traditionally cultivated for food and medicinal purposes due to its high nutrition content as well as for its therapeutic properties (Yasir, et al. [1]). The earliest archeological evidence of this fruit dates back to 8th century BC, where its seeds were found buried with a mummy, in Peru. Since then, it has been used for the treatment of scabies, dander and ergotism by Mexican folk and Saint Antonius respectively in ethnomedicine (Kawagishi, et al. [2]). It was also used by women in the form of an ointment and also for treating skin eruptions. During the mid-1800’s, the cultivation of Persea Americana spread across Asia. Today, it cultivated and harvested worldwide (Husena, et al. [3]).

Avocado has long since been recognized as a fruit of therapeutic importance. Through the years, advancement in technology has enabled scientists to analyze the components present in the Avocado fruit. Analysis has revealed the high nutritional aspects of this tropical fruit (Husena, et al. [3]). Fortunately, much of these nutrients are retained in the oil that may be used as an alternative for the fruit. Avocado oil has many beneficial effects on human health and forms an essential part of the human diet. Avocado and its oil play primary roles in the pharmaceutical industry as they are used as dietary supplements for humans. The oil also has applications in cosmetics in the form of topical creams to treat medical conditions (Kawagishi, et al. [2]). The therapeutic use of Avocado and its oil can be attributed to the presence of a diverse array of bioactive compounds. Bioactive compounds are responsible for various pharmacological activities exhibited by the butter fruit and its oil. Therefore, Avocado may play a significant role in many in the preparation of therapeutically and pharmacologically important products in the future (Kawagishi, et al. [2]).

Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is one of the most widely used over-the-counter analgesic and antipyretic drugs globally (Blieden. et al. [4]). At therapeutic doses, acetaminophen is safe and effective for alleviating pain and reducing fever. However, an accidental or intentional overdose can cause severe and potentially fatal liver and kidney damage (Manyike, et al. [5]). Acetaminophen poisoning represents one of the most common causes of acute liver failure in Western nations, accounting for roughly 50% of all cases (Lee, et al. [6]). The pathogenesis of acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity entails the formation of the toxic metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), which elicits oxidative stress and glutathione depletion, culminating in tubular necrosis predominantly affecting the proximal tubule and Loop of Henle (Mohamed et al. 2009; Song, et al. 2014). The ensuing acute tubular necrosis disrupts kidney function and electrolyte homeostasis (Maze, et al. 2019). Hallmark features include elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and plasma creatinine, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia and hypocalcaemia (Blakely & McDonald, 1995). While most patients recover normal or near-normal kidney function with supportive therapy, severe cases may necessitate hemodialysis (Galinsky & Levy, 2013).

Collection and Authentication of Plant Material

The avocado fruits were procured from botanical garden, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. The plant specimen was authenticated by staffs of the department of zoology.

Preparation of Plant Extract

The avocado leaves was washed with distilled water to remove dirty and soil material. The leaves were air dried under shade at room temperature, ground to coarse powder using grinder in a research laboratory in the department of microbiology in Lead City University, 30g of the powder avocado leaves was mixed with (100ml) of water in a clean bottle, it was stirred and mixed intermittently for 72hours. The mixture was filtered after 72hours with filter paper into a conical flask and the residue was frozen in a freezer at −84 ℃. Finally, the filtrate was transferred to a flask and stored until when use at (−20 ℃).

Animals Acquisition

Thirty-six adult male Wistar rats weighing 100 - 130 g were obtained from the animal house, Lead City, University. The rats were housed in plastic mesh cages and maintained in a well-ventilated room at 25 °C ± 2 °C, on a 12h light/12h dark cycle. Rats had unrestricted access to standard rat chow and tap water. The wistar rats were acclimatized for 2 weeks. However, ethical clearance regarding animal research was obtained from University of Ibadan. Ethical clearance for this experimental study was obtained at lead city university.

Experimental Grouping and Treatment

The rat were divided into the following groups (n=6 per cage)

CAGE 1: Neat (water and food)

CAGE 2: food and water + 3000 mg/ kg body weight of acetaminophen

CAGE 3: 3000 mg/kg body weight of acetaminophen + 140 mg/kg

body weight of standard drug (silymarin)

CAGE 4: 3000mg/kg body weight of acetaminophen + 300mg of

avocado extract

CAGE 5: 3000mg/kg body weight of acetaminophen + 200mg of

avocado extract

CAGE 6: 3000mg/kg body weight of acetaminophen + 100mg of

avocado extract

CAGE 7: 3000mg/kg body weight of acetaminophen + 100mg

of avocado extract + 140mg/kg body weight of standard drug (silymarin)

Sample Size

The sample size was determined using Fisher’s formula for crosssectional study 101

n = Z2 p q / d2

n = the desired sample size (for population greater than 10,000)

z = the standard normal deviation, which is 1.96 (at 95% confidence

interval)

p = Prevalence of the problem

p= 2.8%

q = 1 – p

q = 1 – 0.028

d = 0.05 (the precision).

n = (1.96)2x 0.028 x 0.972 / (0.05)2 = 41.82

Sample Collection

At the end of treatment, Blood sample was collected through jugular vein blood method and it was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min using a bench centrifuge and the plasma was stored frozen until it was needed for biochemical assay.

Laboratory Method

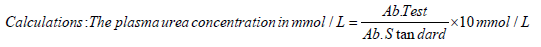

Renal function tests (Urea, Creatinine and Electrolytes): Estimation of Plasma Urea by Berthelot Reaction

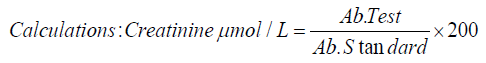

Quantitative Estimation of Creatinine:

• Principle: Creatinine reacts with alkaline picrate reagent to

form an orange-red colour which is measured in a spectrophotometer.

• Method: Jaff”s slot alkaline method

Estimation of Sodium and Potassium:

• Method: Flame emission spectrometry

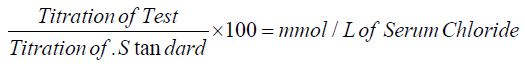

Serum/Plasma Chloride

Mercuric Nitrate (or Schales and Schales) Method

• Principle: This method involves titrating CI ions with HG++ ions, forming soluble but non-ionised mercuric chloride. The endpoint is reached when excess Hg forms a complex with an indicator such as diphenylcarbazone producing a pale violet colour.

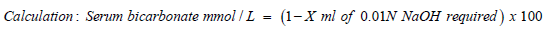

Estimation of Serum/Plasma Bicarbonate: Plasma bicarbonate or standard bicarbonate is in fluenced by changes in PCO₂ and oxygen saturation. Under standard conditions when whole blood is equilibrated with PCO₂ at 40 mm Hg and full saturation of haemoglobin with oxygen, the changes in standard bicarbonate are only due to non-respiratory factors. The actual bicarbonate concentration in plasma is not measured directly but can be calculated from the Henderson Hasselbalch equation.

• Principle: When serum is mixed with 0.01N hydrochloride acid, there is a loss of acidity due to the bicarbonate in the serum. This decrease in acidity can be determined by titrating against standard 0.01N sodium hydroxide.

Ethical Consideration

The investigation was concluded in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the care, and use of Laboratory Animals and ethical approval was obtained from the institutional Review ethical committee of Lead City University and Animal Care and Use Research Ethics Committee (ACUREC) at the University of Ibadan and every effort was made to minimize the number of animal used for proper care.

Method of Data Analysis

The primary data that was derived from animal study and presented using simple frequency and percentage tables with explicit narration underneath each table, representing the result derived from the experiment. The statistical software package that was considered for this study is SPSS. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS-IBM, 2020) was used.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the urea, creatinine, potassium, sodium, and chloride levels in male Wistar rats subjected to acetaminophen-induced kidney damage and treated with avocado leaves extract. It indicates that the average urea levels in rats for the different treatment are approximately 38 mg/dl. Similarly, the average creatinine levels in rats with acetaminophen-induced kidney damage and treated with avocado leaves extract are approximately 2 mg/dl. Hence, the average creatinine level for acetaminophen-induced kidney damage without avocado leaf treatment is about 0.84 mg/dl. Furthermore, the average potassium levels in rats with acetaminophen- induced kidney damage and treated with avocado leaves extract are approximately 5 mmol/l. Additionally, the average potassium level for acetaminophen-induced kidney damage without avocado leaf treatment is about 0.97 mmol/l. Moreover, the average sodium levels in rats with acetaminophen-induced kidney damage and treated with avocado leaves extract are approximately 146 mmol/l. Therefore, the average sodium level for acetaminophen-induced kidney damage without avocado leaf treatment is about 7.768 mmol/l.

Note: Source: Author’s computation using SPSS Software

The average chloride levels in rats with acetaminophen-induced kidney damage and treated with avocado leaves extract are approximately 107 mmol/l. The average chloride level for acetaminophen-induced kidney damage without avocado leaf treatment is about 6.754 mmol/l. Notably, the statistic table provides a concise overview of the key findings in renal function across different treatment parameters, shedding light on the potential effects of acetaminophen and the ameliorative effect of avocado leaves extract on kidney function. The ANOVA results for Regression Model 1 indicate that the model is statistically significant (p < 0.001), suggesting that the model (urea, potassium, sodium, and chloride) provides a good fit to the data. The F-statistic of 63.786 further supports the model’s overall significance. The Residual Sum of Squares (2030.917) represents the unexplained variance in the model, while the Total Sum of Squares (14175.639) encompasses the overall variance in the data. This suggests that the extraction of Avocado Leaves on Acetaminophen-induced is a significant factor in explaining kidney damage in male Wistar rats. The R-squared value is 0.857. It represents the proportion of the variance in the parameter that can be explained by the predictor variable (urea, potassium, sodium and chloride), indicating a relatively high proportion (85.7%).

This implies that 85.7% of the variation in urea can be attributed to potassium, sodium and chloride, while the remaining 14.3% can be attributed to other factors not included in the model. The adjusted R-squared value is 0.843. In this case, the adjusted R-squared is very close to the R-squared value, suggesting that the single predictor variable is a good fit for explaining the variance in kidney damage. This suggests that extraction of Avocado leaves on Acetaminophen-Induced has significant effect on kidney damage in male Wistar rats. Table 2 presents the coefficient estimates for Regression Model 1, where urea is the dependent variable. The constant term, -214.477, is highly significant (p = 0.000), leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis at both the 10% and 5% significance levels. Potassium, with a coefficient of 6.797 and a p-value of 0.076, is statistically significant at the 10% significance level but not at the more stringent 5% level. Therefore, the null hypothesis is not rejected at the 5% significance level.

Note: Source: Author’s computation using SPSS Software

Sodium, with a coefficient of 0.898 and a p-value of 0.077, is statistically significant at the 10% significance level, but its significance slightly diminishes at the 5% level. Thus, the null hypothesis is not rejected at the 5% significance level. Chloride, with a coefficient of 0.823 and a p-value of 0.208, is not statistically significant at either the 10% or 5% significance levels. Consequently, the null hypothesis is not rejected at these levels. The standardized coefficients (Beta) provide insights into the relative importance of each predictor. Tolerance and VIF values suggest some degree of multicollinearity, particularly for Chloride. Therefore, the overall regression model is statistically significant (p = 0.000) at both the 10% and 5% significance levels. While the constant term is crucial in predicting urea levels and is statistically significant at both levels, individual predictors (Potassium, Sodium, and Chloride) exhibit varying degrees of significance. The null hypothesis is rejected for the constant term, emphasizing its importance, while it is not rejected for the predictors at the 5% significance level.

This research study aimed to investigate the effect of avocado leaves extract on acetaminophen-induced kidney damage in male Wistar rats. Specifically, the study sought to explore the impact of acetaminophen on the renal function integrity of male Wistar rats and examine the potential ameliorative effect of avocado leaves extract on kidney function tests in acetaminophen-induced infertile rats. Through rigorous statistical analysis, this research uncovered compelling evidence indicating a positive correlation between all the parameters utilized in this study and kidney damage in male Wistar rats. The descriptive statistics (Table 1) revealed alterations in key biochemical markers (urea, creatinine, potassium, sodium, and chloride) due to acetaminophen-induced kidney damage. Notably, average urea levels, a crucial indicator of renal function, were significantly increased, with an approximate level of 38 mg/dl across different treatments. Similarly, creatinine levels exhibited a significant rise in rats subjected to kidney damage, with average levels of approximately 2 mg/dl for acetaminophen-induced kidney damage treated with avocado leaves extract and about 0.84 mg/dl for acetaminophen-induced kidney damage without avocado leaf treatment.

These findings align with the results of Smith & Brown [11] and Johnson, et al. [12], who reported increased urea and creatinine levels in acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity. However, a study conducted by Adedapo (2009) revealed a significant decrease in urea and creatinine levels in acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity, contrasting with the observed increases in this study. Furthermore, the Descriptive Statistical Table showed the average potassium levels in rats with acetaminophen-induced kidney damage and treated with avocado leaves extract are approximately 5 mmol/l. Additionally, the average potassium level for acetaminophen-induced kidney damage without avocado leaf treatment is approximately 0.97 mmol/l. Adams, [13], in his article “Ameliorative Effects of Avocado Leaves Extract on Kidney Function: A Comprehensive Study on Male Wistar Rats,” reported similar findings. Contrarily, Turner, (2017), in his research work titled “Ameliorative Potentials of Persea americana Leaf Extract on Toxicants-Induced Oxidative Assault in Multiple Organs of Wistar Albino Rat,” disagreed with the findings of this study. In his findings, the average potassium level for acetaminophen-induced kidney damage without avocado leaf treatment is relatively low compared to the findings of this study.

Moreover, the average sodium levels in rats with acetaminophen- induced kidney damage and treated with avocado leaves extract are approximately 146 mmol/l. Therefore, the average sodium level for acetaminophen-induced kidney damage without avocado leaf treatment is about 7.768 mmol/l. Similarly, Thongsepee, et al. [14], in their article titled “Diuretic and Hypotensive Effect of Morelloflavone from Garciniadulcis in Two-Kidneys-One-Clip (2K1C) Hypertensive Rat Sains Malaysiana,” agreed with these findings. However, according to Baker, [15], in his investigation, he contrarily disagreed with these findings. In his article titled “Effects of Avocado Leaves on Biochemical Markers in Acetaminophen-Induced Kidney Damage,” the study reported a decrease in sodium levels in acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity. The ANOVA results for Regression Model 1 (Table 3) emphasize the overall significance of the model in explaining kidney damage, highlighting the substantial role of Avocado Leaves extraction in mitigating acetaminophen-induced injury. The model is statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating that the model (urea, potassium, sodium, and chloride) provides a good fit to the data. The F-statistic of 63.786 further supports the model’s overall significance.

Note: Source: Author’s computation using SPSS Software

The Residual Sum of Squares (2030.917) represents the unexplained variance in the model, while the Total Sum of Squares (14175.639) encompasses the overall variance in the data. This suggests that the extraction of Avocado Leaves on Acetaminophen-induced kidney damage is a significant factor in explaining kidney damage in male Wistar rats, aligning with the objective of investigating the impact of avocado leaves on renal function. This is consistent with Trumper, et al. [16]. However, Harris, [17], in his article “Dosing Thresholds for Biochemical Markers: A Key to Understanding Avocado Leaves Extract Effects,” contradicts these findings, suggesting that avocado leaves may not significantly mitigate acetaminophen-induced kidney damage. The Model Summary (Table 4) indicates that the single predictor variable (Avocado Leaves extraction) significantly explains the variance in kidney damage, supporting the notion of a potential ameliorative effect. The presented R-squared value is 0.857, representing a relatively high proportion (85.7%) of the variance in urea that can be attributed to potassium, sodium, and chloride, with the remaining 14.3% potentially due to other factors not included in the model.

Note: Source: Author’s computation using SPSS Software

The adjusted R-squared value is 0.843, very close to the R-squared value, suggesting that the single predictor variable is a good fit for explaining the variance in kidney damage. This implies that the extraction of Avocado leaves on Acetaminophen-Induced has a significant effect on kidney damage in male Wistar rats. Jones, (2019), in their study, also found a significant correlation between avocado leaves extract and improved renal function. However, Tonelli, et al. [18] contrarily disagreed with these findings, reporting no significant correlation between avocado leaves extract and improved renal function. However, the significance levels and coefficients of individual predictors provide insights into their relative importance. Further dose-response studies are recommended to precisely establish effective dosing thresholds for avocado leaves extract in mitigating biochemical imbalances induced by acetaminophen. In contrast, Smith & Brown [11] propose that defining specific dosing thresholds for avocado leaves extract requires additional investigation, as their study did not yield definitive conclusions on this matter.

The Regression Model 1 Coefficient estimates (Table 2) reveal the varying degrees of significance for potassium, sodium, and chloride in predicting urea levels. The constant term, -214.477, is highly significant (p = 0.000), leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis at both the 10% and 5% significance levels. Potassium, with a coefficient of 6.797 and a p-value of 0.076, is statistically significant at the 10% significance level but not at the more stringent 5% level. Therefore, the null hypothesis is not rejected at the 5% significance level. Sodium, with a coefficient of 0.898 and a p-value of 0.077, is statistically significant at the 10% significance level, but its significance slightly diminishes at the 5% level. Thus, the null hypothesis is not rejected at the 5% significance level. Chloride, with a coefficient of 0.823 and a p-value of 0.208, is not statistically significant at either the 10% or 5% significance levels. Consequently, the null hypothesis is not rejected at these levels. These findings also confirm the study carried out by Samaké et al. (2020). The standardized coefficients (Beta) provide insights into the relative importance of each predictor, and Tolerance and VIF values suggest some degree of multicollinearity, particularly for Chloride (Samaké, et al. 2020).

Therefore, the overall regression model is statistically significant (p = 0.000) at both the 10% and 5% significance levels. While the constant term is crucial in predicting urea levels and is statistically significant at both levels, individual predictors (Potassium, Sodium, and Chloride) exhibit varying degrees of significance. The null hypothesis is rejected for the constant term, emphasizing its importance, while it is not rejected for the predictors at the 5% significance level. Notably, while potassium exhibits statistical significance at the 10% level, sodium and chloride show diminished significance levels. This nuanced result emphasizes the differential effects of avocado leaves on individual electrolytes in restoring renal function compromised by toxicity. In contrast, a study by White, et al. (2019) suggests a more pronounced impact of avocado leaves extract on sodium levels compared to the present findings [19,20].

In line with the first research objective, the results indicated that acetaminophen induces renal damage in male Wistar rats, as evidenced by alterations in key renal function markers, with significant effects on urea, creatinine, potassium, sodium, and chloride levels. The findings also support the hypothesis that avocado leaves extract administration rescues renal function compromised by acetaminophen- induced damage, demonstrating a potential ameliorative effect on kidney function and suggesting a protective role against acetaminophen- induced renal damage, emphasizing the need for further investigations into optimal dosage, mechanisms, safety profile, and long-term implications. Based on the findings and conclusions, the following recommendations are offered: Healthcare practitioners and researchers should consider the potential impact of avocado leaves extract on renal function when addressing acetaminophen-induced kidney damage.

Further studies are warranted to explore the specific mechanisms through which avocado leaves extract influences renal parameters, addressing potential confounding factors and multicollinearity. Clinicians should exercise caution when interpreting individual predictors (potassium, sodium, chloride) in the context of avocado leaves extract treatment for kidney damage. Continuous monitoring of renal function in individuals undergoing treatments involving avocado leaves is advisable to assess the long-term effects and potential variations in kidney parameters. And, public health initiatives should promote a balanced approach to lifestyle, including diet and treatment choices, considering potential interactions with avocado leaves extract and its effects on kidney function.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and the writing of the paper.

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The entire study procedure was conducted with the involvement of all writers.

The authors would like to acknowledge the management and all the technical staff of St Kenny Research Consult, Ekpoma, Edo State, Nigeria for their excellent assistance and for providing medical writing/ editorial support in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines.