Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Letteria Tomasello1*, Miriana Ranno, Angela Alibrandi2 and Graziella Zitelli

Received: August 27, 2024; Published: September 03,2024

*Corresponding author: Letteria Tomasello, Department of Cognitive Sciences, Psychology, Education, and Cultural Studies, University of Messina, Italy

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.58.009158

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating, neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system and which etiology is still unknown. It is one of the principal causes of non-traumatic neurological disability in young adults The disease is progressive and characterized by various symptoms, compromising motor, sensory and psycho-cognitive impairments. The unpredictable evolution of MS is associated with a reduction in physical and emotional performance. We investigate the relationship between locus of control and life’s quality in Multiple sclerosis patients.

Keywords: Multiple Sclerosis; Locus of control; Quality of Life

Abbreviations: MS: Multiple Sclerosis; CNS: Chronic Nervous System; PF: Physical Functioning; RP: Role Physical; BP: Bodily Pain; GH: General Health; VT: Vitality; SF: Social Functioning; RE: Role Emotional; MH: Mental Health; PCS: Physical Composite Score; MCS: Mental Composite Score

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the central nervous system (CNS) in which the immune system attacks myelin sheaths, the insulating layer that forms around the nerves of the CNS [1]. This neurodegeneration can lead to a variety of clinical symptoms that can vary from patient to patient. People living with Multiple Sclerosis live with Multiple Sclerosis symptoms that may manifest as difficulty walking, muscle spasms, or weakness. Other symptoms, may include fatigue, mood changes, cognitive changes, physical and emotional pain, spasticity, bowel/bladder dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, and vision changes [2,3]. As Multiple Sclerosis is a chronic neurodegenerative condition with an unpredictable prognosis, it appears, from studies conducted, to be among the diseases that greatly impact patients' quality of life [4,5]. From the research conducted, it is found that MS patients perceive a level of quality of life, lower than the general population [6,7].

Quality of life is a multidimensional concept that encompasses the domains enunciated by the World Health Organization regarding the concept of health: it is "...a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not simply the absence of disease or infirmity" [8]. The identification of risk and protective factors aimed at improving the quality of life, receives increasing attention and its importance is growing to date [9,10], in this regard, the aim of the present research is to evaluate the quality of life and Locus of control, in patients diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis under drug treatment of I and II line.

Locus of control was developed by Julian B. Rotter in 1954 is the degree to which people believe that they, as opposed to external forces (beyond their influence), have control over the outcome of events in their lives. A person's Locus is conceptualized as internal (a belief that one can control one's own life) or external (a belief that life is controlled by outside factors which the person cannot influence, or that chance or fate controls their lives) [11]. Individuals with a strong internal locus of control believe events in their lives are primarily a result of their own action. Rotter (1975) cautioned that internality and externality represent two ends of a continuum, not an either/or typology. Internals tend to attribute outcomes of events to their own control. People who have internal locus of control believe that the outcomes of their actions are results of their own abilities. They also believe that every action has its consequence, which makes them accept the fact that things happen and it depends on them if they want to have control over it or not. Externals attribute outcomes of events to external circumstances. A person with an external locus of control will tend to believe that their present circumstances are not the effect of their own influence, decisions, or control, and even that their own actions are a result of external factors, such as fate, luck, history, the influence of powerful forces, or individually or unspecified others (and/or a belief that the world is too complex for one to predict or influence its outcomes. Laying blame on others for one's own circumstances with the implication is an indicator of a tendency toward an external locus of control.

Therefore, LoC is a useful predictor of the ability to manage chronic disease and a good QoL indicator in patients suffering from various diseases [12,13]. In health care, it has been estimated that those with in-house Loc (IHLOC) follow health-promoting behaviors, including regular checkups and adherence to medical prescriptions [14-17]. LOC may be adaptive, an external HLOC (EHLOC) may actually be beneficial, challenging assumptions about what leads to the most effective psychological search in the face of difficult circumstances Research suggests that the LOC may be adaptive and that an external HLOC (EHLOC) may in fact be beneficial, challenging assumptions about what leads to the most effective psychological search in the face of difficult circumstances [18-20]. Scholars have examined the relationship between HLOC and chronic diseases in a number of health conditions [21]. Study results, have found positive correlations between IHLOC and Quality of Life (QoL), some have noted benefits of an EHLOC and questioned the clear distinction between IHLOC and EHLOC in the context of chronic disease. However, research on HLOC and MS is scarce [22]. In this study we will examine the relationship between locus of control and life's quality in patients with the diagnosis of relapsing remitting Multiple Sclerosis.

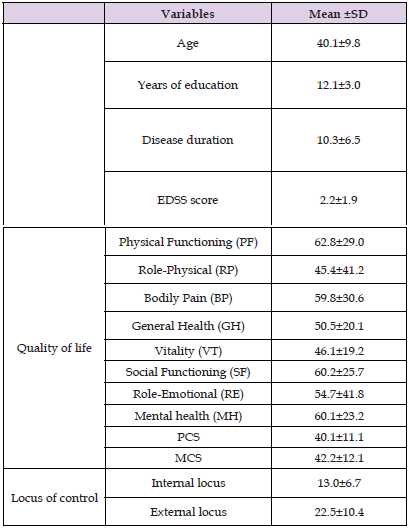

Patients

We enrolled 87 patients (66.7% women, 33.3% men; mean age 42.1) They were followed periodically at our Multiple Sclerosis Center of the Polyclinic Ospital of Messina. Description of the examined sample (Table 1). The patients had a disability corresponding to a mean score of 2.2 on EDSS. As regards the medical treatment, 57.5% of them had been treated with interferon; the remaining 42.5% had been treated with monoclonal antibodies.

Inclusion Criteria: diagnosis of MS according to the revised McDonald criteria [23]; the lack of relapse within 90 days preceding the enrollment; lack of other medical conditions, psychotic disorders, identified by the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, version V; and absence of MS-related cognitive problems such as impairment of attention, information processing speed, memory, or executive functions. The study followed the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the survey. They were assured that the transcript of the interview would remain strictly confidential and that patients would not be named in the final description and analysis.

Clinical Evaluation

QoL was assessed using the SF-36 questionnaire, instead clinical disease progression was assessed using EDSS; LoC was used for psychological variable [24] SF-36 questionnaire consists of 36 items, which are used to calculate eight subscales: Physical Functioning (PF), Role Physical (RP), Bodily Pain (BP), General Health (GH), Vitality (VT), Social Functioning (SF), Role Emotional (RE), and Mental Health (MH). The first four scores can be summed to create the Physical Composite Score (PCS), while the last four can be summed to create the Mental Composite Score (MCS). Scores for the SF-36 scales range between 0 and 100, with higher scores indicating a better HRQoL. EDSS is a method of quantifying disability in MS and monitoring changes in the level of disability over time. It is widely used in clinical trials and in the assessment of people with MS. EDSS ranges from 0 to 10 in 0.5-unit increments that represent higher levels of disability. Scoring is based on an examination by a neurologist. EDSS steps 1.0 to 4.5 refer to people with MS who can walk without any aid and is based on measures of impairment in eight Functional Systems (FS) [25]. The LoC Scale (LCS) is a 29-item questionnaire that measures an individual's level of internal versus external control of reinforcement [12].

Statistical Analysis

The numerical data were expressed as mean and standard deviations; the categorical variables as number and percentage. The nonparametric Spearman correlation test was applied in order to assess the existence of significant interdependence between EDSS and all variables related to individual profile (physical activity, etc.) and to standardized profile (ISF and ISM). The same test was applied to assess the correlation between disease duration and above-mentioned variables. Mann Whitney test was used to assess the existence of significant differences, for all examined variables, between patients undergoing first and second line 2 treatments. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 for Window package (P<0.05 two sided was considered to be statistically significant).

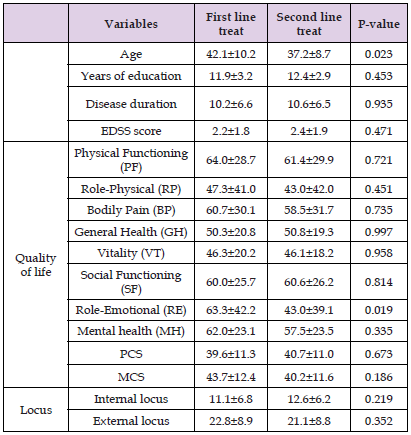

(Tables 1-3) We found a significant positive correlation between years of disease and EDSS (p = 0.004), so the EDSS increases with the increasing of disease years (Table 4) In addiction, there were no significant correlations between years of disease and the life's quality perception. On the contrary, the EDSS was significantly correlated to all the life's quality indexes (p < 0.001), but it was not correlated to "mental health." The perception of general health and and the physical state indicator decreased only with the increasing of the patient's age (p = 0.007; p = 0.009). Comparing the different types of medical treatment, there were no significant differences, except for the parameter "emotional role limitation" (p = 0.019), which was significantly higher in the group of interferon treated patients (mean 63.3 ± 42.2) compared to monoclonal antibodies ones (mean 43.0 ± 39.1). Lastly, the locus of control analysis showed an external locus prevalence both for patients attending the first line (mean 22.8±8.9) and the second line (mean 21.1±8.8) treatment; on the contrary, an internal locus was present only in few patients attending the first line (mean 11.1±6.8) and the second line (mean 12.6±6.2) treatment (Table 5).

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics of Demographic Parameters, EDSS, Quality of Life, Locus of Controls Measured on Enrolled Patients.

Note: PCS: Physical Component Summary MCS: Mental Component Summary

Table 3: Mean ±SD and Comparison between Patients Undergoing First and Second Line Treatment (Demographic Parameters, EDSS, Quality of life, Coping Strategies, and Locus of Controls).

Note: PCS: Physical Component Summary MCS: Mental Component Summary

Note: PCS: Physical Component Summary MCS: Mental Component Summary

Note: PCS: Physical Component Summary MCS: Mental Component Summary

Studies in the literature suggest that individuals with higher disability as measured by the EDSS have an EHLOC that played a predominant role on the evolution of health status. These data contribute in being able to state that EHLOC is not a fixed personality trait, but is mutable based on life circumstances and challenges. Scholars [22], observed in their longitudinal study that individuals initially classified as having an internal LOC changed their beliefs by experiencing an EHLOC as their condition progressed. DuCette [26] advanced the hypothesis that the unpredictability of illness and the lack of control condition, may cause attitudes to change with particular regard to health conditions. Living with a chronic and disabling disease such as MS, can make patients experience a sense of helplessness and control of the health condition, advanced levels of disability are more likely to express an EHLOC. In their longitudinal study of patients with Multiple Sclerosis, [22] found that with disease progression, individuals were likely to move from an IHLOC to an EHLOC. Most studies on LOC in general, and HLOC in particular, stress the positive aspects of holding an IHLOC rather than an EHLOC and emphasize the correlation between an IHLOC and positive health behaviors including treatment adherence, exercise and healthy lifestyle choices. The results showed that patients with an external locus of control had lower perceptions of physical pain (p = 0.0003), vitality (p = 0.019), social activity (p = 0.0022), physical condition indicator (p = 0.017) and disease state indicator (p = 0.019).

On the other hand, internal locus reduced the perception of "mental health" (p = 0.006) and illness status indicator (p = 0.018). The results of this study, although limited to mild disability, underscore the importance of clinical implications and the importance of paying attention to mental health in the care and adherence to therapeutic treatment prescribed by specialists. The clinical relevance of the relationship between quality of life and locus of control, as reflected in our study, provided insight into the overall health status of patients and may also help clinicians choose the best treatment, especially considering the significant role of treatment adherence. Receiving a diagnosis of MS, undoubtedly means, having to revolutionize one's existence and future plans, along the course of the disease, people with MS, have to live with the unpredictability of the disease and its related symptoms and submit to the limitations that disability imposes. Knowing patients' perceptions of the disease, their beliefs, and their perceived quality of life, along with assessing cognitive function and the emotional and behavioral component, could contribute to their quality of life and negotiating realistic expectations for care. Psychologists and other mental health professionals, should be involved within a multidisciplinary team, providing psychological care and identifying any factors, which may reduce the individual's ability to adapt to the looming challenges that the chronic disease condition imperiously threatens. Psychotherapists must be aware of their intrusion into a system whose equilibrium is threatened by disease-induced change. This entails painful acceptance by the patient, of the new condition and knowledge of its possible progress, with the full range of intense emotions and complex interactions.