Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Birendra Kumar Jha1*, Mingma Lhamu Sherpa2, Jitendra Kumar Singh3 and Chamma Gupta4

Received: August 16, 2024; Published: August 26, 2024

*Corresponding author: Dr. Birendra Kumar Jha, Department of Biochemistry, Janaki Madical College, Tribhuwan University, Janakpurdham, Madhesh Province, Nepal

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.58.009145

Background: Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP) has recognized as a valid marker of Coronary Heart Diseases in

obese adults. Studies on AIP and its association to obesity in Nepal are inadequate.

Objective: To evaluate the AIP and its association with CVD risk factors in obese adults.

Methods: The cross-sectional study included 378 obese people. Participants information was gathered using

a questionnaire. Following clinical and physical assessments venous blood was drawn, analyzed for lipid

profile, fasting blood sugar, CRP-US and fibrinogen. AIP was determined using log10(triglycerides/high density

lipoprotein-cholesterol) and further classified as low (<0.11), intermediate (0.11-0.24) and high (≥0.24) CVD

risk. CVD risk factors were defined as per international guidelines.

Results: The mean age of the participants was 45.50±13.01. 92.59% of the participants had high, 4.76% had

intermediate, and 1.58% had low CVD risk. The AIP showed a noteworthy correlation with fibrinogen (r=0.102,

p=0.049), total cholesterol (r=0.138, p=0.007), waist circumference (r=0.119, p=0.020), fasting blood sugar

(r=0.128, p=0.013), Castelli Risk Index-I (r=-.530, p=<0.001), Castelli Risk Index-II (r=0.444, p=<0.001), and

Atherogenic coefficient (0.876, p=<0.001).

Conclusion: Significantly elevated AIP and its noteworthy association with CVD risk factors suggest that AIP

may be an important tool for clinicians when risk-stratifying obese patients.

Keywords: Obese; CRP; Fibrinogen; Atherogenic Index of Plasma; Cardiovascular Risk Factors; Nepal

Abbreviations: AIP: Atherogenic Index of Plasma; CVD: Cardiovascular Diseases; NCDs: Non-Communicable Diseases; HDL-C: High Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; CRI: Castelli Risk Index; AC: Atherogenic Cofficient; AI: Atherogenic Index; BMI: Body Mass Index; CDC: Complete Diagnostic Center

Obesity is one of the main ongoing global health crises and its incidence is rising rapidly, particularly in low- and middle-income nations [1]. The overall prevalence of obesity (defined as MBI≥30kg.m2) and overweight (defined as body mass index; MBI≥25kg/m2) has increased during the past few years in the adult population [2]. According to the report of 2016, 1.9 billion individuals were found to be overweight and 650 million of them were obese [2]. In addition, the prevalence of obesity has tripled globally between 1975 and 2016. According to recent prediction by World Obesity Federation (WOF), a billion individuals worldwide i.e. one in five females and one in seven males—would be obese by 2030 [3]. Furthermore, Southeast Asia’s obesity incidence is predicted to have doubled by 2030. It has been observed that between 1996 and 2016, the prevalence of obesity in Nepal increased from 0.2% to 4.1% [4]. Obesity has become a major global health focus due to its significant association with non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as cardiovascular diseases (CVD) fatty liver diseases, metabolic syndrome (Mets), obstructive sleep apnea type 2 diabetes mellitus (type 2 DM), hypertension (HTN), as well as several cancer cases [2]. Obesity has a complicated aetiology that includes genetic, behavioral, social, environmental, and physiological components. Chronic positive energy balance, controlled by intricate endocrine tissue interactions, is the cause of obesity [5].

It has been reported that positive energy balance-induced adipocyte hypertrophy is associated with ectopic fat accumulation, metabolic abnormalities, and organelle dysfunction [6]. In such conditions, the most common CVD risk factors including that of atherogenic dyslipidemia, type 2 DM, and HTN become highly prevalent; intensify CVD risk [7]. Moreover, visceral fat accumulation has reported secreting pro-inflammatory as well as pro-thrombotic adipokines, leading to tissue damage and oxidative stress [8]. It has been observed that visceral adipose tissue is associated with alterations in the release of adipokines, compromised mitochondrial function, and alterations in the metabolism of lipid and glucose. Moreover, Obesity has been also found involved in an increase of inflammatory and prothrombotic state may be a crucial factor contributing to a higher susceptibility to CVD [9]. Obesity induced alteration in lipid chemistry resulted in dyslipidemia atherogenesis, which was observed as a critical cause in the development of CVD. Due to its role in the progression of atherosclerosis, low density lipoprotein (LDL-C) has long been the principal target in therapy for the prevention of coronary heart disease [10]. The term atherogenic dyslipidemia (AD) is described as increased level of triglycerides (TG) and LDL-C and reduced level of high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) [11]. A new marker of atherogenic dyslipidemia, atherogenic index (AI), has been proposed recently, along with the Castelli Risk Index (CRI) and Atherogenic Cofficient (A.C.) to facilitate an efficient evaluation and prediction of the risk of CVD [12]. Dyslipidemia, proinflammatory and prothrombotic state are known as crucial moderator of atherosclerosis which is a pathological condition involved in the initiation and progression of CVD [13].

C-reactive protein ultra-sensitive (CRP-US), known as a classic indicator for low grade inflammation and has recognized as a inflammatory biomarker [14]. Fibrinogen, a prothrombotic biomarker, produced by hepatocyte in response to interlukin-1, interlukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-α. An elevated plasma fibrinogen concentration has observed associated with increased risk, incidence and severity of CHD [15]. The information of the AIP profile along with its cardiovascular risk factor correlates has considered as a key for the categorization for CVD risk and found effective in starting appropriate drugs of cardiovascular benefit or to manage CVD at primary stage in low-middle income countries like Nepal [16-17]. In addition of AIP, markers of obesity such as BMI, WC, atherogenic indices, proinflammatory and prothrombotic status markers have been found to be associated to increased CVD risk [13,15,18]. Henceforth, the evidence of this correlational study would be beneficial for estimating risks for CVD at medical facilities where lipid profiling may not be done. Thus, the present research aimed to assess the metabolic profile of AIP and its association with cardiovascular risk variables in obese individuals in Nepal.

This community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in three Terai districts of Nepal’s Madhesh Province from December 2019 to March 2020. Through a collaborative approach established between the government health service network and the study team, the community was made informed about the research. The participants for the study were selected on the basis of their central obesity, as per IDF criteria (WC ≥90cm in male and ≥80cm in female). A systematic questionnaire was used to gather specific information about the study subjects. Population below 18 years, having WC <90cm in male and <80cm in female were excluded. In total 378 adults were enrolled in the study by organizing camps in the different regions of the districts. Every single participant underwent clinical and physical assessments (WC, weight, and height), and an adequate volume of fasting venous blood was collected with maintaining aseptic conditions. Once the blood was drawn, the serum was separated by centrifugation and transported to a lab for additional processing. Fasting blood sugar, triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL-C, LDL-c were estimated by using ERBA chem-5 semi-auto analyzer (enzymatic method) while CRP-US was determined by Gr8 semi-auto analyzer (immunoturbidimetry method).

The ethical approval against this study was obtained from Institute of Medicine, Trubhuwan University (approval number: 110(6- 11-E)071/072). Different formula were used to to calculate the biological values. “Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP)” was estimated using Log10(TG/DDL-C) ratio [19], Castelli Risk Index 1 (CRI-1) was estimated by TC/HDL-C ratio, while Castelli Risk Index II (CRI-II) was determined as LDL-C/HDL-C. In addition, Atherogenic Cofficient (A.C.) was estimated by using formula (TC-HDL-C)/HDL-C [20].

Systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, LDL-C ≥ 100 mg/dl and total cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dl were considered as CVD risk factors [17]. Additionally, a body mass index (BMI) more than and equals to 25 kg/m2, waist circumference ≥ 80 cm in women and ≥90 cm in men, fasting blood sugar ≥110 mg/dl were also considered as CVD risk factors [21]. CRP-US of ≥1mg/dl and fibrinogen concentration of ≥3.51 gm/l was considered as CVD risk factors [22, 23]. On the basis of AIP, CVD risk was categorized as low (<0.1), medium (0.1-<0.24) and high (≥0.24) risk [19]. As per CRI I and II, ≥3.5 and ≥3.0 were considered as high CVD risk. However for A.C. <3.0 was defined as low CVD risk [20].

SPSS version 25 was used for data analysis after they were coded, verified for accuracy, and entered into an SPSS data sheet. Chi-square tests were utilized for comparison of descriptive analysis and categorical data. The Pearson chi-square correlation test was used to examine the relationship between AIP and cardiovascular risk parameters. “A statistically significant value was defined as a p value less than 5.05”.

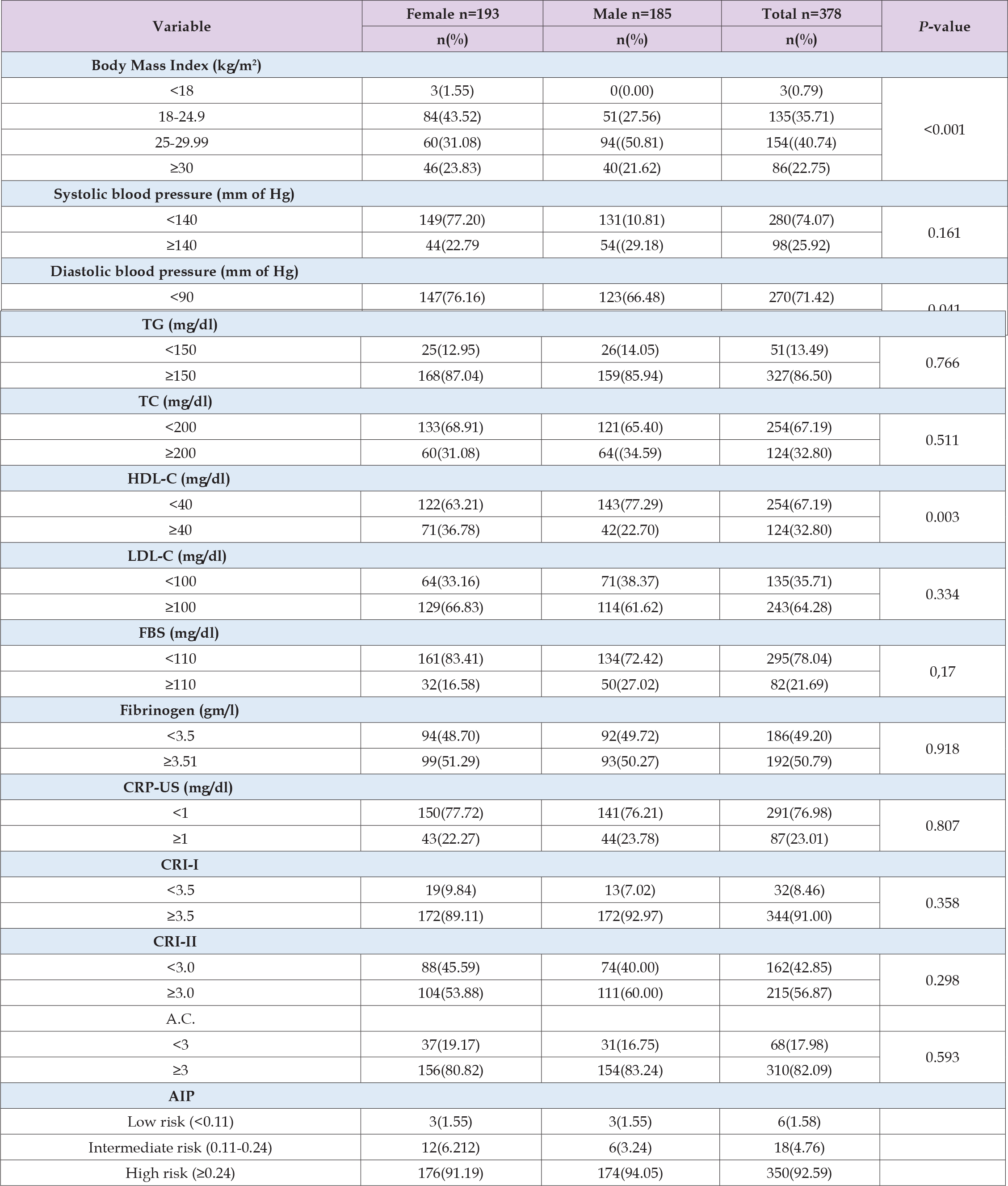

Of the 378 individuals that were involved in the study, 185 (48.94%) were male and 193 (51.05%) were female. The mean age of the participants was 45.50±13.01. Of the participants, 110 (29.10%) corresponded to the age group of 31–40 years, and 102 (26.98%) to the age group of 41–50 years. 238 participants, or 62.96% of the total, had only completed primary school, while 176 participants, or 46.56%, worked in households. A significant proportion of the individuals (330; 87.30%) did not consume alcohol, and 340; 89.94%) did not smoke. One fourth (25.39%) of participants had family income of between NRS 15,000-24,999, while 16.66% had of ≥ NRS50,000, as presented in Table 1. Out of 378, 154(40.74%) study participants had BMI in between of 25-29.99 kg/m2 and 86(22.75%) had ≥30 kg/ m2, with significant difference in male and female (p=<0.001). An increased systolic and diastolic BP were observed in 98(25.92%) and 108(28.57%) of study participants respectively. However, diastolic blood pressure only has shown a significant difference between male and female participant with p=0.041. An increased level of TG, TC and LDL-C were observed in 327(86.50%), 124(32.80%) and 243(64.28%) of participants respectively, without any significant difference among male and female. The mean±SD of FBS was obtained as 102.89±43.09 and an elevated level of ≥110mg/dl of FBS was found in 82(21.69%) of participants. The prothrombotic status marker, fibrinogen and proinflammatory marker CRP-US were observed ≥3.51gm/l and ≥1 mg/l in 192(50.79%) and 87(23.01%) of participants respectively, as presented on Table 2. Among 378, 350(92.59%) had high, 18(4.76%) had intermediate and 6(1.58%) had low AIP, with the mean AIP with 0.61±0.23, Figure 1. The cardiovascular indices; an increased CRI-I (≥3.5) and CRI-II (≥3) were observed in 344 (91%) and 215(56.87%) of the participants, without significant gender differences. Furthermore, 310(82.09%) of the study participants had elevated level of A.C. and there was no significant difference observed among male and female, as presented on Table 2. To examine the relationship between AIP and cardiovascular risk variables, a Pearson’s correlation was used Figure 2. The statistical analysis suggested a strong positive association between AIP and the following variables: fibrinogen (r=0.102, p=0.049), TC (r=0.138, p=0.007), FBS (r=0.128, p=0.013), CRI-I (r=0.530, p=<0.001), CRI-II (r=0.444, p=<0.001), and A.C. (r=0.876, p=<0.001). Nonetheless, there was only a marginally significant connection between AIP and BMI (r=o.053, p=0.493), CRPUS (r=0.093, p=0.071), and LDL-C (r=0.065, p=0.207). Table 3 shows the relationship between cardiovascular risk factors and AIP Table 4.

Note: *Nepalese Rupees.

Table 2: Clinical, anthropometric characteristics and laboratory measurements of study participants (n=378).

Note: TG: triglycerides, TC: total cholesterol, HDL-C: high density lipoprotein-cholesterol, LDL-C: low density lipoprotein-cholesterol, FBS: fasting blood sugar, CRP-US: C-reactive protein-ultra sensitive, CRI-I: castelli risk factor-I, CRI-II: castelli risk factor-II, A.C.: atherogenic coefficient, AIP: atherogenic index of plasma.

Note: WC: west circumference, LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein, BMI: body mass index, TC: total cholesterol, FBS: fasting blood sugar, CRP-US: c-reactive protein ultra-sensitive; CRI-I: castelli risk index I, CRI-II: Castelli risk index II, A.C: atherogenic coefficient, r: pearson’s correlation coefficient.

Note: WC:west circumference, BMI: Body mass index, TG: triglycerides, TC: total clolesterol, HDL-C: high density lipoprotein-cholesterol, LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein, FBS: fasting blood sugar, CRP-US: C-reactive protein ultra-sensitive; CRI-I: castelli risk index I, CRI-II: castelli risk index II, AIP: atherogenic index of plasma, A.C: atherogenic coefficient, r: pearson’s correlation coefficient.

We evaluated the AIP and its relationship to CVD risk variables in this present study in the obese adults of three Tarai districts of Nepal. The results of the study demonstrate that a significant percentage of the obese participants in the studied region (92.59%) had high AIP, with no noticeable gender difference. Moreover, poorly controlled CVD risk factors were present in the majority of obese patients. A substantial positive correlation between AI and WC, TC, FBS, Fibrinogen, CRI-I, CRI-II, and A.C. was observed. Comparable results were observed in a case control findings in Turkey, with a 55.2% of the obese adult participants had AIP level of high and 33.7% had intermediate CVD risk [24]. An increased proportion AIP level of high CVD risk in our study can be partially explained by the fact that our study exclusively included obese people in its enrollment criteria. Furthermore, comparable research results from Uganda have been shared, whereby type 2 diabetes patients’ AIP and CVD correlations were examined. It was revealed that high-risk AIP was present in 36.4% of type 2 diabetic participants, while intermediate-risk AIP was present in 18.6% of participants [25]. A substantial positive association between AIP and CRI-I (r=0.530**, p=<0.001), CRI-II (r=0.444**, p=<0.001), and A.C. (0.876**, p=<0.001) was found in our study. S. Bhardwaj et al. did a study that was similar and observed significantly higher levels of AIP, A.C., CRI-I, and CRI-II in patients who had angiographical confirmation [26].

Atherosclerosis is a pathological condition that is implicated in the onset and progression of cardiovascular disease (CVD). It is crucially moderated by atherogenic dyslipidemia, prothrombosis, and inflammation [13]. Prothormobitc (fibrinogen) and proinflammatory (CRP-US) markers were found to be increased in our investigation. One marker that has been identified as a CVD risk factor is CRP-US. Of the obese participants, 23.01% had a CRP-US level of ≥1 mg/dl; no statistically significant differences was found between the male and female groups. However, our investigation did not find a significant association between CRP-US and AIP. A revisiting research carried out in Bermingham by S. Ishii et al. revealed a favourable correlation between hs-CRP and obesity [27]. A similar strong positive correlation between BMI and CRP was found in a research involving 16,616 adult individuals [28]. Fibrinogen, a widely recognised indicator of prothrombotic state that is produced by the liver in response to interleukin I, interleukin 6, and tumour necrosis factor-α, was observed to be elevated in over 50% of the individuals who were obese (50.79%). In people who are obese, fibrinogen is an independent risk factor for CVD, much like CRP. Furthermore, a significant positive connection (r=0.102*, p=0.049) was observed between fibrinogen and AIP. In the study by M. Hafez, et al. [29], obese children had a significantly elevated amount of fibrinogen as compared to the control group. Another study that looked at obese adolescents found a significant higher amount of fibrinogen and a positive correlation with CRP [30]. AIP and WC showed a positive significant relationship in our study (r=0.119*, p=0.020), which is similar with findings from a number of other studies [31, 32, 33].

On the other hand, there was no discernible relationship between AIP and BMI in our investigation. The majority (40.74%) of the participants had MBI of in between 25 to 29.99 kg/m2, followed with 22.75% of MBI ≥30 kg/m2. A high proportion of high BMI among the participants might be due to the selection criteria obeyed for the study. Among the study participants, 25.92% had systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mm of Hg, 28.57% had diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 mm of Hg, 86.50% had TG of ≥150 mg/dl, TC of ≥ 200 mg/dl, 64.28% had of LDL ≥100 mg/dl, 21.69% had FBS of ≥110 mg/dl and 32.80% had HDL-C of ≤40 mg/dl. Other studies [34, 35] also revealed results regarding lipid profile aspects that were similar to ours. It is widely acknowledged that low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) plays a critical role in the development of atherosclerosis, which ultimately results in cardiovascular disease (CVD). In our study, although 243 (64,28%) out of 378 patients had increased LDL-C levels, there was no significant correlation found between them with AIP. Consistent with our results, a further investigation found that while LDL-C was elevated in 78.4% of subjects, there was no noteworthy correlation between AIP and LDL-C [25]. FBS and AIP have a strong positive connection in this study (r=1.128*, p=0.013), which is similar to the results of studies by P. Bansal, et al. [36] and S. Reza et al. [37]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the foremost study evaluating the AIP and relation to cardiovascular risk factors in a community population of Nepali. The prothrombotic state and proinflammatory indicators, as well as their correlation with AIP, were examined in our research, despite the paucity of research on obesity and atherogenic dyslipedimia. These comprise our study’s main strength. The study, which examined the correlation of AIP with risk factors associated with CVDs, only examined a small portion of three districts in Nepal’s Tarai region; as a result, it is unable to determine the causal effect correlation between AIP and other cardiovascular risk factors.

Our study results suggest that levels of AIP were notably elevated and showed significant positive associations with cardiovascular risk factors in obese adults from the Tarai regions of Nepal. Merely exhibiting a high AIP level may suggest that initial treatment for cardiovascular disease management and lifestyle modifications are necessary.

None.

Birendra Kumar Jha and Mingma Lhamu Sherpa and Chamma Gupta conceptualized and designed the study. Birendra Kumar Jha and Jitendra Kumar Singh performed the statistical analysis. Birendra Kumar Jha was the principal investigator and contributed to manuscript writing along with Chamma Gupta. All the authors revised and approved the final version.

The authors would like to express gratitude to the district public health officer of Dhanusha, Mahottari and Sarlahi for their valuable cooperation, as well as to the study participants for their active involvement, without which the study would not have been possible. The authors would also like to thank Complete Diagnostic Center (CDC) Pvt. Ltd. on Hospital Road in Janakpurdham, Dhanusha, Madhesh Province, Nepal for providing laboratory support.