Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Gebeyehu Alkadir (BSc, MSc, Veterinary Parasitologist)* and Chaltu Wana

Received: August 01, 2024; Published: August 21, 2024

*Corresponding author: Gebeyehu Alkadir (BSc, MSc, Veterinary Parasitologist), Addis Ababa University College of Veterinary Medicine & Agriculture, Department of Veterinary Pathology & Parasitology, P.O.Box 34, Bishoftu, Ethiopia

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.58.009134

Further studies could also explore the potential for combining multiple diagnostic methods for a more accurate and reliable diagnosis of Haemonchus contortus infection in small ruminants. Additionally, the development of rapid diagnostic tests for haemonchosis could greatly benefit small ruminant farmers by providing quick and accurate results in field settings. This study included 79 small ruminants with suspected gastrointestinal nematode infections. Faecal samples were analysed using the floatation technique to identify strongyle-type nematode eggs. The number of eggs per gram was estimated using the McMaster counting technique, represented by the FEC/EPG. For animals with positive FEC results, larval cultures and Packed cell volume tests were performed to confirm the presence of Haemonchus contortus larvae. The investigation revealed a statistically significant negative association between the test methods of faecal egg count (FEC) and packed cell volume (PCV). Animals with higher faecal egg counts, indicating heavier parasite burdens, had lower PCV levels, aligning with the expected anaemia caused by haemonchosis. While both faecal egg count (FEC) and packed cell volume (PCV) provided insights into potential Haemonchosis infection, the study suggests limitations with PCV. Faecal egg count (FEC) offers a more direct measurement of parasite burden through egg count, whereas PCV is influenced by various factors beyond parasite infection. Additionally, larval culture confirmed the presence of Haemonchus contortus in animals with a positive faecal egg count (FEC). Overall, the findings from this study contribute to our understanding of haemonchosis diagnosis and highlight the importance of early detection for targeted selective treatment in small ruminants.

Keywords: Haemonchus contortus; Larval Culture; Faecal Egg Count; Packed Cell Volume

Abbreviations: FEC: Faecal Egg Count; EPG: Eggs Per Gram; PCV: Packed Cell Volume; LC: Larval Culture

Ethiopia, where there are over 25.5 million sheep and 24.06 million goats, small ruminants are vital to the livelihoods of farmers who lack resources [1,2]. Small ruminants (sheep and goats) are vital to the livelihoods of Ethiopian farmers, particularly those that lack resources [3,4]. Important gastrointestinal strongyle nematodes that infect small ruminants include Haemonchus contortus, Teladorsagia circumcincta, and the intestinal species Trichostrongylus [5,6]. Sheep are usually infected with one or more nematodes, but the severity of the disease can vary considerably [7,8]. Disease is predominantly linked to factors such as the species and number of worms infecting the host, the immunological and health status of the host, and environmental factors such as climate and pasture type, stress, stocking rate, management, and/or diet [9,10]. Three main groups of animals are susceptible to high-intensity infections:

i. Young, non-immune animals;

ii. Adult, immune-compromised animals;

iii. Animals exposed to large numbers of L3s from the environment [10-13].

Nematode populations in sheep are usually over-dispersed, with the majority of sheep having low and only a few sheep with high intensities of infection, respectively [10,13,14]. In addition to supporting research into the ecology and epidemiology of nematode infections, correct diagnosis is essential for the successful management of these diseases and can significantly aid in monitoring anthelmintic resistance in strongyle populations [10]. Because of the overuse and unregulated use of broad-spectrum anthelmintic (which fall into three main classes: benzimidazoles, imidazothiazoles, and macrocyclic lactones), such resistance has become a significant economic and bionomic issue [15]. A variety of clinical symptoms, including scouring, anaemia, loss of body condition, and mortality in extreme situations, are indicative of gastrointestinal nematode-caused disease [16,17]. The type and quantity of worms present, the host's nutritional status, and the host's immunological and reproductive state all have an impact on the nature and severity of clinical manifestations, as indicated by the Hungerford indicators [18]. These clinical approaches are also arbitrary and nonspecific [19-21]. The most commonly used technique for diagnosing gastrointestinal nematode infections is the counting of worm eggs in excrement. This technique can be used in most diagnostic situations because it is low-cost, simple to apply, and does not require sophisticated instrumentation. One of the important uses of this technique is the estimation of infection intensity [6,22]. Traditionally, Faecal Egg Count (FEC) using the modified McMaster technique has been the primary method for diagnosing gastrointestinal parasites and determining the need for anthelmintic treatment [23].

Although Faecal Egg Count (FEC) is widely used and relatively inexpensive, it has significant drawbacks and detection delays. It takes three to four weeks for worm eggs to appear in faeces after infection, by which time the animal might already be experiencing negative health consequences [13,24-26]. This method involves mixing faeces with a saturated salt or sugar solution (e.g., sodium nitrate or sucrose; specific gravity: 1.1–1.3) to float parasite eggs (with the exception of trematode eggs) on the surface of the suspension. An aliquot of this suspension was aspirated, eggs were counted, and the number was expressed as eggs per gram (EPG). This delay necessitates exploration of alternative diagnostic techniques. Therefore, effective diagnostic tools are crucial for managing Haemonchosis and preserving the health and productivity of small ruminants [27,28]. Larval culture involves incubating faecal samples containing eggs of strongyle nematodes to allow L1s to hatch and then develop into L3s; the latter are examined microscopically and differentiated morphologically/morphometrically.

A number of protocols have been published by different researchers [29,30], which differ in the temperatures, times and media used for culture, and the approach of larval recovery [15,31]. In addition to conventional copro-diagnostic methods, various immunological and biochemical methods have been assessed or established, aimed at the specific diagnosis of infection [32-34]. These methods rely mainly on the detection and measurement of parameters, such as pepsinogen, gastrin or specific antibody in serum, which might be indicative of parasite infections as illustrated in [15,24] protocols for the specific diagnosis of gastrointestinal nematode infections in small ruminants [25,35]. The Packed Cell Volume (PCV) measures the percentage of red blood cells in an animal's blood sample. Haemonchus contortus feeds on blood from the abomasum (fourth stomach) of ruminants, leading to anaemia and a decrease in PCV levels [36]. This suggests that PCV could potentially serve as a rapid diagnostic indicator of haemonchosis.

Exploring alternative diagnostic tools, such as PCV, alongside FEC holds promise for more efficient haemonchosis management. Identifying infected animals allows for timely intervention and minimizes the negative impacts on animal health and productivity [25,37,38]. Therefore, based on the hypothesis that packed cell volume (PCV) techniques might be a superior diagnostic tool than estimation of parasite burden or intensity, this study was aimed to compare the efficacy, and sensitivity of the three methods such as faecal egg count (FEC) and larval culture (LC), with packed cell volume (PCV) techniques under field settings for the diagnosis of haemonchosis in small ruminants grazing on communal pastures in Bishoftu town, Ethiopia.

Study Area

The study was carried out in Bishoftu town in Ethiopia, situated at 9°N latitude and 40°E longitude, with an elevation of approximately 185 m (1.15 mi) in the central highlands of Ethiopia as illustrated in Figure 1. Bishoftu City experiences an annual rainfall of about 866 mm (2.84 ft), with 84% occurring during the rainy season from June to September, which is bimodal. The average annual maximum and minimum temperatures were approximately 26°C and 14°C, respectively.

Study Animals

Small ruminants were used in this study. Accordingly, data representing the categories of sex, species, age, and body condition scores were recorded during sample collection.

Faecal Sample Collection and Examinations

Faecal samples for parasitological examination were collected directly from the rectum of each sheep and goat using disposable gloves, placed in a universal bottle, and kept in a cooler box with ice packs. The samples were then transported to the CVMA Veterinary Parasitology Laboratory at Bishoftu, and immediately examined or stored at 4°C until further examination. Three grams of Crushed faecal samples were mixed with 40–50 ml of sodium chloride (flotation solution) and stirred. The suspension was filtered through a tea strainer using a 2. The filtered suspension was then poured into test tubes, and a cover slip was placed on top of the filled test tube. Eggs were allowed to float for 10–15 min. Finally, the samples were examined under a 10x magnifying microscope. For faecal samples that were positive for strongyle-type nematodes, the Modified McMaster egg counting technique was used to identify the degree of infestation, as described previously [39]. The McMaster quantitative technique was used to determine the number of eggs per gram of faeces, and each number obtained was multiplied by a factor of 100 to obtain an approximate number of eggs per gram of faeces. A sub-sample was drawn from each sample using disposable pipettes, and both chambers of the McMaster slides were filled and observed under a microscope at 100× following standard procedures. Finally, the total number of eggs per animal was recorded.

Identification of Nematode Larvae, and Counting of Total Larvae

Faecal samples that screened positive for strongyle-type nematode eggs were cultured for harvesting and identification of third-stage larvae of the Haemonchus species harbouring sheep and goats, according to [39,40] for individual animals. The samples were placed in a jar and left for an entire week. Water was added to the culture every two days throughout this time. The larvae were harvested by adding water to the culture jar until the water meniscus protruded above the jar lip, covering the jar mouth with an overturned Petri dish, and holding the Petri dish in place while the jar was inverted. The culture jar was then filled with water and left to stand for a few minutes to allow air to escape from the culture. Water was then added to the Petri dish and the rim of the jar was lifted slightly from the bottom of the dish on one side by slipping two glass microscope slides under it. The preparation was left for a few hours for L3 to migrate into the water and settle before the water in the Petri dish was removed with a pipette for larval identification and counting. The culture was repeatedly harvested over several days by holding the jar at a slant with the mouth pointing downwards, spraying the inner walls with a wash bottle, and allowing the larval suspension to drain into suitable containers. The larvae were counted and subjected to morphological examination to identify genera. A few drops of iodine solution were added to the tube to immobilize and stain the larvae, and each larva was examined under a microscope using (10-40X times) objective lenses as procedure by [13,40].

Blood Sample Collection and Determination of Packed Cell Volume

Blood samples were collected from the jugular vein of each animal using EDTA tubes containing anticoagulants. Blood samples collected in anticoagulants were transported to the laboratory using an icebox at the Parasitology Laboratory of the AAU-CVMA. The packed-cell volume technique was employed. The third quarter of the blood was collected using a capillary tube and slanted. The sealed microhematocrit capillary tubes containing blood were centrifuged using a microhematocrit centrifuge for 5 min at 12,000 rpm. After centrifugation, the packed cell volume (PCV) value was recorded for the estimation of anaemia using a haematocrit reader as per the protocol described previously [40,41].

Data Analysis

After different data were collected, they were entered into an Excel format, and descriptive statistical tests were used to verify the association between variables. After comparing the groups of variables, p-values were calculated using STATA software packages of generalized linear models.

Descriptive Statistic for the Test Methods Analysis

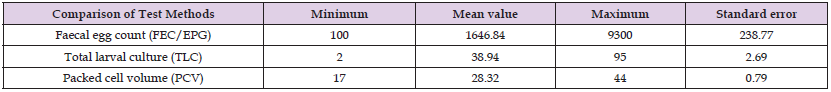

According to these findings, 79 animals tested positive for gastrointestinal nematode eggs resembling strongyle-type eggs using faecal floatation technique protocols [38,42]. A faecal egg count (EGP) was performed for each animal that tested positive. Based on the faecal egg count, the findings showed that there is a high burden of gastrointestinal nematode infection, with a maximum of 9300 eggs in single animals. The average number of eggs counted (EPG) (means) was 1646.84+238.77, indicating a higher level of infection of the animals with strongyle-type nematode eggs, particularly on the basis of blood-feeding nematode parasites. However, because our investigation focused on the field of haemonchosis, it was necessary to compare the results with the packed cell volume as illustrated in Table 1. The findings showed that PCV values detected ranged from to 17-44. Whereas the average value is 28.32+0.79 (mean + SE) as indicated in Table 1. In the step of faecal larval count techniques, the total larval count was conducted per sample of the individual animals that tested positive for strong nematode eggs following the procedures described by [43].

Table 1: Descriptive Statistic for Faecal Egg Count (EPG), Packed Cell Volume (PCV), And Total Larval Count (TLC).

After the total number of harvested larvae was counted per individual animal sample, their identification was performed based on the characteristic features of their cranial and caudal extremities, as previously described [40]. Based on this, using a fixed volume of larval suspension of (5ML) the presence of Haemonchus species was identified and the percentage was calculated. Based on this procedure, the results show the percentage of haemonchus contortus species fell within the range of 2-95%. Average value of haemonchus. contortus larvae detected (Means) was 38.94+2.69 which indicating that it is preferable to use PCV to detect the presence of naturally occurring infections in small ruminants, as illustrated in Table 1. The graph indicated in Figure 2 shows the relationship between Eggs Per Gram (EPG) of faeces by faecal floatation technique using McMaster counting technique and Packed Cell Volume (PCV), providing valuable insights into the diagnosis of haemonchosis. The negative correlation between EPG and PCV highlights the potential for using these techniques as diagnostic tools for naturally occurring haemonchosis in sheep under field conditions.

Association of Faecal Egg Count (FEC_EPG) with PCV and Risk Factors

This study explored an initial insight on the relationship between the test methods of faecal egg count (FEC/EPG), packed cell volume, and various factors. Accordingly, the use of packed cell volume (PCV) techniques for the diagnosis of haemonchosis in small ruminants in field conditions as parasitological tests has a statistically significant negative association (P-value = 0.027) with faecal egg count (FEC/EPG). This suggests that due to parasite burden, as the faecal egg count (FEC) increases, the PCV (red blood cell count (PCV) tends to decrease, which aligns with haemonchosis causing anaemia as indicated in Table 2. In parallel to conducting the faecal examinations and blood examinations by packed cell volume tests, other factors, such as species, age, sex, and body conditions of the animals were analysed. Based on this, species and sex were not significantly (P>0.05) associated with the faecal egg count (FEC/EPG) as potential factors. Age showed a statistically significant positive association (p = 0.010) with FEC_EPG. This suggests that older animals may have a higher parasite burden than younger animals. There was a statistically significant positive association (p = 0.001) between body condition score and FEC/EPG. This suggests that it might be because animals with poor body conditions are more likely to be heavily parasitic than animals with a good body condition score due to increased nutrient intake (compensatory feeding).

Association of Total larval count (TLC) with PCV and Risk Factors

Faecal culture was also conducted after the number of eggs was counted for each animal. The larvae were then isolated from individual animals and the number of H. contortus larvae was counted after the total count of parasite larvae. Accordingly, there was a significant negative association between the number of H. contortus larvae, determined using the total larval count technique, and PCV (p = 0.000). This suggests that animals with higher larval species in the genus Haemonchus. contortus had a lower PCV. However, there was no significant association between the total larval count and species (p = 0.257), sex (p = 0.868), or body condition score (p = 0.179). However, age had a statistically significant positive association with the total larval count (p = 0.017). This suggests that older sheep tend to have higher total larval counts, representing parasites harbouring small ruminants. These findings also revealed the presence of haemonchus contortus species in the total larval count increased by (0.711) factors, and the level of packed cell volume significantly decreased by a factor of 0.01796, owing to the presence of blood-feeding parasites.

The Correlation coefficients of PCV are shown in Table 1. There was a negative correlation between species and PCV, and there were significant correlations between species and PCV (P=0.000). However, there was no significant association the between the total larval count and species (p = 0.257), sex (p = 0.868), or body condition score (p = 0.179). However, age had a statistically significant positive association with the total larval count (p = 0.017). This suggests that older sheep tend to have higher total larval counts, representing parasites harbouring small ruminants. These findings also revealed the presence of haemonchus. contortus larvae in the total larval count increased by (0.711) factors, and the level of packed cell volume significantly decreased by a factor of 0.01796, owing to the presence of blood-feeding parasites.

The Correlation coefficients of PCV are shown in Table 1. There was a negative correlation between species and PCV, and there were significant correlations between species and PCV (P=0.000). However, there is a weak relationship between the packed cell volume and BCS. All the correlation coefficients with positive signs with p-values less than 0.05, and 95% confidence intervals, have significant positive correlations between the test methods and other considered factors affecting the interpretation of the results, as indicated in Tables 2 & 3.

Haemonchus contortus is one of the most dominant and pathogenic parasites infesting the stomach of ruminants, irrespective of age, gender, and breed of the host throughout the world, leading to enormous losses in various ways, including Ethiopia [33]. So as far as early and accurate diagnosis of the parasite is crucial for effective disease management and improved animal health outcomes, several diagnostic tools have been implemented by several researchers, such as [20,34,44-48]. Traditionally, faecal egg count (FEC) has been the primary diagnostic tool for gastrointestinal nematodes; however, it has limitations, such as delays in egg shedding after infection [22-49]. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of packed cell volume (PCV) as a complementary diagnostic tool for haemonchosis in small ruminants under field conditions in Bishoftu town, Ethiopia. The findings revealed a statistically significant negative association between FEC and PCV (P =0.027) (Table 2). Animals with higher FEC, indicating heavier parasite burdens, had correspondingly lower PCV levels, aligning with the expected anaemia caused by Haemonchus feeding on blood, which is consistent with the study conducted by (Hassum, et al. [24,50]) on the validation of the FAMACHA© eye colour technique for detecting anaemic sheep and goats in the Jigjiga Zone of the Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia [14-15,51]. This suggests a potential role for PCV as a rapid indicator of haemonchosis in field settings. However, regardless of parasite infection, due to various factors such as nutritional deficiencies and other diseases causing blood loss, certain limitations of using PCV as the sole diagnostic tool need to be considered [52].

Additionally, the sensitivity of PCV for detecting haemonchosis might be lower than faecal egg count (FEC) as illustrated in Table 3, which directly measures parasite egg burden, which might be due to mixed infection by gastrointestinal nematodes [44]. This is also supported by our finding that larval culture confirmed the presence of Haemonchus contortus in animals with positive faecal egg count (FEC) results, which is inconsistent with the study conducted by [17,43,53], highlighting the potential for false negatives with packed cell volume (PCV) alone [22]. Our current study provides evidence for previous research suggesting that FEC offers a more direct measurement of parasite burden and sensitivity than the packed cell volume (PCV) technique [21,44] in a field setting. While PCV may provide insights into potential anaemia, a hallmark consequence of haemonchosis, its limitations necessitate a combined approach with FEC for a more comprehensive diagnosis and strongly agree with the study conducted by different researchers [23,36]. Furthermore, this study identified age as a significant risk factor associated with both FEC and total larval count (Tables 2 & 3). This aligns with existing knowledge that younger animals tend to have a less developed immune response against haemonchosis, leading to higher parasite burdens compared to older animals [24]. Comparing the techniques of total larval count (LC) to packed cell volume (PCV), both are utilized in diagnosing of the infection haemonchosis in small ruminants [54-56].

However, because PCV measures the volume of red blood cells in a blood sample, it has been accepted as the preferred method for detecting natural infections using small ruminant larval culture techniques. This study revealed an inverse relationship between PCV and total larval count (TLC), indicating that as the number of parasite larvae rises, the PCV (red blood cell count) tends to decline, consistent with the presence of blood-feeding nematode parasites leading to anaemia [6,31]. Therefore, according to the findings, the study has forwarded the following conclusions and recommendations:

• PCV is a more reliable diagnostic tool than Faecal Larval Culture (FLC) for identifying haemonchosis in sheep. This is because PCV accurately reflects the degree of anaemia resulting from the parasite load, while FLC may not consistently signify the seriousness of the infection in field conditions, in which this study agrees with different researchers [26-27].

• This study highlights the potential value of using packed cell volume (PCV) as a rapid field-based indicator of haemonchosis, particularly when combined with faecal egg count (FEC).

• The negative correlation between FEC and PCV supports this notion. However, the limitations of PCV and the superior sensitivity of FEC for parasite burden detection emphasize the importance of a combined approach for definitive diagnosis [57,58].

• Future research with larger sample sizes and refined diagnostic evaluations, including investigating the sensitivity and specificity of the employed coproscopic techniques, could further solidify the efficacy of this combined approach haemonchosis diagnosis in resource-limited settings.

• Implementing such field-friendly diagnostic tools can empower veterinarians and farmers to effectively manage haemonchosis, thereby improving animal health, productivity, and economic outcomes in small ruminant production systems.