Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Gemechu Gure1, Dursa Miressa2 and Adugna Girma3*

Received: August 05, 2024; Published: August 16, 2024

*Corresponding author: Adugna Girma Lema, Yemalogi welel Woreda livestock and fisheries development office. Kellem Wollega, Oromia, Ethioipa

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.58.009125

Poultry production is one of the key livestock subsectors of Ethiopia. It plays important roles in terms of generating employment opportunities, improving family nutrition, and empowering women. It is a suitable business for poor households due to the small quantity of land needed and low investment costs required starting up and running the operation. The current poultry population of Ethiopia is estimated to be around 60 million out of which the majority (37.9 percent or 22.7 million) are chicks and only 33.6 percent (20.2 million) are laying hens. About 56 percent (9.6 million) of Ethiopian households have poultry holdings with varying range of flock size. However, about 80 percent of the households with poultry keep from 1 to 9 chickens. The sector is indeed dominated by extensive scavenging and small extensive scavenging family poultry production systems. Despite of these Ethiopian huge chicken flocks, there are different factors such as diseases, predators, lack of proper healthcare feed source and poor marketing information that hinder the productivity of the chickens in most area of the country. Because of this it is important to make awareness in the community in the form review on major economic contribution and constraints of poultry production and productivity to create systematic and scientific ways of disease control, prevention and improved management of chicken production which is poor in the country.

Keywords: Constraints; Economic Contribution; Ethiopia; Poultry; Production

Abbreviations: HACCP: Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points; LMP: Livestock Master Plan; SFRB: Scavenging Feed Resource Base; FAO: Food and Agriculture Organization; NCD: Newcastle Disease; NVI: National Veterinary Institute; HB1: Hitchener B1; RIR: Rhode Island Red

Ethiopia is the primary country by Livestock population in Africa, with around 59.5 million cattle,30.7 million sheep and about similar number of goats, 1.2 million camels and 59.5 million chickens which play a significant role as source of food and income in addition to several other important economic and sociocultural functions CSA, et al. [1]. Poultry production as part of livestock production could be one alternative income generating mechanism and improving nutritional status for rural households in developing counties including Ethiopia (Holloway and Ehui, et al.). In addition, it may contribute to poverty alleviation and socio-economic inclusion of vulnerable groups such as the urban poor, women, the disabled, orphans, and the unemployed to provide them with a decent livelihood (Gororo, Mabel, et al. [2]). Moreover, poultry production stimulates local economic development of urban centers through the development of related micro-enterprises wholly or partly responsible for the provision of inputs and processing, packaging, and marketing of outputs as well as the provision of services to the sector (Mutami, et al. [3]). Ethiopia has about 60% of the total chicken population of East Africa, which includes local, exotic and hybrid chicken breeds. About 97% of the Ethiopian poultry population consists of indigenous chickens, while the remaining 3% consists of imported exotic and hybrid breeds of chickens. Even though there is no recorded information which indicates when and by whom the first batch of exotic breeds of chickens were introduced to Ethiopia, the introduced improved chicken breeds have been found to play significant roles in human nutrition and as a source of income (Fulas, et al. [4]).

The poultry production system in Ethiopia is indigenous and an integral part of farming system and predominantly prevailing in the country and it is characterized by small flock, minimal input and unorganized marketing system (Feleke et al. [5]). Poultry in Ethiopia provides the following benefits: production of eggs for hatching, sale and home consumption, and production of birds for sale, processing, replacement, and home consumption (Tadelle et al., 2007). Chicken have a short generation interval and higher feed conversion efficiency, thus providing a cheap source of animal protein and also chicken meat is the most palatable and easily digestible animal meat and contains essential amino acids required for human beings, and eggs are richly endowed with nutrients (Yared, et al. [6]). Even if, Ethiopia owned huge chicken flock; there are different factors like diseases, predators, lack of proper healthcare, feed source and poor marketing information that hinder the productivity of the chickens in most area of the country. All of the above obstacles are, among the main constraints incriminated for reduction of total numbers and compromised productivity in the poultry farm; even though they have well recorded and documented for awareness creation and other purposes (Natnael, et al. [7]).

Therefore, the objective of this review paper is to overview the major economic contribution and constraints of poultry production and productivity in Ethiopia.

Poultry Production System in Ethiopia

The poultry sector in Ethiopia can be characterized into three major production systems based on some selected parameters such as breed, flock size, housing, feed, health, technology, and bio-security (Goutard, Magalhaes, et al. [8]). These are village or backyard poultry production system, small scale poultry production system and commercial poultry production system. Alternatively, the FAO classifies poultry production systems into four sectors, depending on the level of bio-security. Based on this system of classification, Ethiopia has three poultry production systems: ILRI et al. [9] large commercial poultry production with “moderate to high biosecurity” (sector 2), small commercial poultry production with “low to minimal” biosecurity (sector 3) and village or backyard production with “minimal biosecurity" (sector 4) (Nzietcheung, et al. [10]). Note that the poultry sector in Ethiopia plausibly does not contain any sector 1. The sector 2 system of poultry production is developing and the main commercial poultry farms – Elflora, Agro Industry, Genesis and Alema – are located around Bishoftu in Oromia. The sector 3 system is emerging around the urban and peri-urban areas of Ethiopia. In terms of the FAO definition, sector 4 or the village or backyard production represents the main poultry production system in most parts of the country ILRI et al. [11].

Backyard Poultry Production: This system is characterized by a low input (scavenging is almost the only source of diet), low input of veterinary services, minimal level of bio-security, high off-take rates and high levels of mortality. Here, there are little or no inputs for housing, feeding or health care. As such it does not involve investments beyond the cost of the foundation stock, a few handfuls of local grains, and possibly simple night shades, mostly night time housing in the family dwellings. The poultry are kept in close proximity to the human population. Mostly indigenous chickens are kept although some hybrid and exotic breeds may be kept under this system. The few exotic breeds kept under this system are mainly a result of the government extension programs (Nzietcheung, et al. [10]). The size and composition of flocks kept by households vary from year to year owing to various reasons such as mortality from diseases, agricultural activities and household income needs. Mortality in local birds results mainly from disease and predators as well. According to (ILRI, et al. [11]), typical household flock sizes vary from 2 to 15 chickens, and it is a common practice to keep all age and functional groups together. A research report indicated that 62% of small farmers reported disease as the major factor for high mortality while 11% noted predator as a major factor too (Hailemariam, et al. [12]). Newcastle disease is identified as the major killer in the traditional system while other diseases including a number of internal and external parasites contribute to the loss. The incidence of Newcastle disease is widespread during the rainy season. It often wipes out the whole flocks when it strikes.

In particular, it was found that poultry production drops by 50% during the rainy season. Most of the birds kept under the backyard system belong to indigenous poultry. Rearing of indigenous poultry offers farmers nutritional, socio-cultural and economic benefits (Nzietcheung, et al. [10]). In backyard poultry, women are mainly responsible for rearing poultry. The backyard poultry production systems are not business oriented rather destined for satisfying the various needs of farm households. In this case, the major purposes of poultry production include eggs for hatching (51.8%), sale (22.6%), and home consumption (20.2%) while chickens for sale (26.6%) and home consumption (19.5%). The income earned from poultry keeping is used to buy food and clothes for children. Poultry and egg offer a quality protein source throughout most of the year (Aklilu, et al. [13]); (Nzietcheung, et al. [10]). Backyard poultry move freely between families in the village. Movement can also be from household to local market for sale, from market to household in case of unsold chicken or in form of gifts from household to household. This free movement of backyard poultry could contribute to the transmission of many infectious diseases in the backyard system. Birds are left for scavenging system and households put little time, and resource for chicken farming. As a result, poultry output is very low. For instance, local birds lay, on average, 40-60 eggs per annum. Moreover, egg sizes are small and chick survival rates are extremely low. Village hens brood and hatch their own eggs. The high chick mortality rates along with the unsuccessful hatching and rearing are also accounts for low egg production. For instance, 50% of all eggs laid are destined for hatching (Nzietcheung, et al. [10]).

Small-Scale Commercial Poultry Production: In this system, modest flock sizes usually ranging from 50 to 500 exotic breeds are kept for operating on a more commercial basis. Most small-scale poultry farms are located around Bishoftu town in Oromia region and Addis Ababa. This production system is characterized by medium level of feed, water and veterinary service inputs and minimal to low bio-security. Flock sizes vary from 20 to 1000 and the breeds kept are Rhode Island Red (RIR) layers. Most small-scale poultry farms obtain their feed and foundation stock from large-scale commercial farms (Genesis or Alema) (ILRI, 2013).

Large-Scale Commercial Poultry Production: It is a highly intensive production system that involves, on average, greater or equal to 10,000 birds kept under indoor conditions with a medium to high bio-security level. This system heavily depends on imported exotic breeds that require intensive inputs such as feed, housing, health, and modern management system. It is estimated that this sector accounts for nearly 2% of the national poultry population. This system is characterized by higher level of productivity where poultry production is entirely market-oriented to meet the large poultry demand in major cities. The existence of somehow better bio-security practices has reduced chick mortality rates to merely 5% (Bush, et al. [14]). In Ethiopia, the commercial poultry sector is situated mostly in Bishoftu areas. ELFORA, Alema, and Genesis farms are the major large-scale poultry enterprises in Ethiopia that are located in Bishoftu ELFORA, the largest enterprise, supplies about 420,000 chickens and over 34 million eggs per annum to the urban markets in the capital (Abebe, et al. [15]); (Bush, et al. [14]). This supply accounts for close to 60% of the total poultry production from the commercial sector in the Bishoftu areas (Bush, et al. [14]). Alema Farm is the second largest poultry enterprise delivering about 500,000 broilers per annum to the Addis Ababa market (Abebe, et al. [15]). It has its own parent broiler stock from Holland; feed processing plant, hatchery, on-site slaughtering facilities and cold storage rooms as well as its own transport facility. Genesis farm is the third most important private poultry enterprise operating on average between 10,000 to 12,000 layers and has its own parent layer stock and hatchery (Bush, et al. [14]).

Poultry Supply and Demand

Market prices of chicken in Ethiopia are seasonal. Consumer prices generally rise during holidays such as Easter, New Year and Christmas. Consumer price information obtained in June 2017 shows that price of a live bird weighing between 1.5 to 1.8 kg is between 9–10 USD while the retail price for frozen whole chicken produced locally was between 4–5 USD per kg. The reason for this price difference is attributed to the preference of Ethiopian consumers to buying live birds and slaughtering them at home (Aklilu, et al. [13]).

Trade, Marketing and Markets

Domestic Market: Although the current consumption of poultry products in Ethiopian is among the lowest in the world, the domestic market is expected to take off following the trends in the population growth and increasing income. The market share of eggs and chicken meat from exotic breeds is growing. For instance, in 2014 the contribution of exotic chickens to the total national egg output was less than 5 percent CSA et al. [16]. In 2016, exotic breeds contributed to 27.3 percent of the total number of eggs produced nationally CSA et al. [1]. Although traditionally the eggs and meat from exotic breeds are less preferred to the indigenous owing to the existing cooking and consumption habits, the trend is changing. There are large numbers of bulk consumers such as full board public universities and colleges (serving over half a million students), hospitals, hotels and restaurants. Promotion and education on preparation of different food recipes is underway and public awareness on diverse cooking styles is on the rise. None of the major international fast-food brands (e.g. McDonald's or Kentucky Fried Chicken) have restaurants in Ethiopia. The reason is that there are no poultry meat processing plants in Ethiopia meeting the welfare, slaughter, health, biosecurity and Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) standards required by these major fast-food chains FAO et al. [17].

Trade: Poultry and poultry products are probably among the least traded commodities in Ethiopia. Despite the lack of consistent and reliable statistics, some sources indicate that Ethiopia has been importing parent DOCs for many years. All the breeding stock and DOCs used by large scale intensive poultry producers and government multiplication centers are imported. Among the country imported varying quantity of live chickens from 2003 to 2016, largest quantity imported was in 2008 (398 000 heads), with no imports in the subsequent two years, and very small quantities imported afterwards FAO et al. [17]. The only significant volume of chicken meat imported was 130 tonnes recorded in 2013 (Figure 1). Relative to chicken meat substantial volumes of canned chicken meat were imported between 2014 (193 tonnes) and 2016 (141 tonnes). Importers of chicken meat and canned chickens are not clear, but Ethiopian Airlines and some of the international brand hotels in Addis Ababa that serve international customers are probably among the potential ones. Ethiopia has almost no record of exporting either live poultry or any form of processed chicken meat. The Ethiopian Livestock Master Plan (LMP) aims to achieve exportable surplus of poultry meat by 2020. However, export during this planned period appears to be impractical because local demand is expected to surpass supply and also it would be difficult for Ethiopia to compete on price and quality terms with major exporters such as the United States and Brazil (FAO, 2019).An important feature of the poultry marketing is that there are a large number of small scale traders where volume of trade is small ranging from 10 to 50 chickens (Keneal, et al. [18]).

Poultry Health Management

Bio-Security Measures: The biosecurity of the village poultry production system is very poor, as scavenging birds live together with people and other species of livestock. Poultry movement and droppings are very difficult to control and chickens freely roam in the household compound. There is no practice (or even viable means) of isolating sick birds from the household flocks and dead birds are left for either domestic or wild predators. Chickens and eggs are sold on open markets along with other food items. The current live bird marketing system represents a significant and potential hazard to both buyers and sellers, yet implementation of biosecurity and hygienic practices in such a system is generally difficult. The Newcastle Disease experience and the attitude of communities to handling sick birds (which are often sold) shows that marketing systems play a considerable role in the dissemination of disease over wide geographical areas in a relatively short period of time. The first recorded case of Newcastle disease was in 1970 on a poultry farm near Asmara, Eritrea, from where it spread all over Ethiopia within a short period of time. In summary, it is very difficult to apply health and bio-security measures on full day scavenging birds in small flock sizes in Ethiopia (Solomon, et al. [19]).

Disease Control Measures: Diseases were/are one of the major bottlenecks for village chicken productions in the studied areas. Newcastle disease was most widely distributed among the village chicken in Ethiopia. This was reported in several previous studies which employed different diagnostic methods such as virus isolation, sero-epidemiological investigations and molecular methods to confirm the presence of the disease in Ethiopian village chicken productions (Terefe, et al. [20]). According to (Ahmed, et al. [21]) on his survey study, almost 56 to 71% of the visited farms were affected by disease. The disease occurred in all agro-climatic zones during the period studied, particularly affecting chicken in highlands (71.3%). Farmers did not know how to differentiate the disease affecting their chicken in 17.9% of the cases. They knew only symptoms shown by affected chicken. The symptoms most commonly observed in affected village chicken were bloody diarrhea, nasal discharge, sneezing, torticollis and deaths within few days. Only 18.7% of the visited households contacted veterinarians when their chickens were sick (Mulisa, et al. [3]). According to study reported by (Halima, et al. [22]) from northwest Ethiopia that most (72.43 %) farmers do not properly examine their chicken and provide no health management services. Also, another study reported from rift valley of Oromia, that 44% of farmers in the study area usually treat sick chickens using traditional medicine whereas others (41%) do nothing. Only 11% of the farmers consult veterinarians when their chickens get sick; this is as a result of veterinary service insufficiency. They use garlic, different kind of green leaves, lemon, local alcohol, paper powder, butter, etc as drenching, nasal application and smoking. The response to treatment varies considerably where 45% fully recovered, 33% partially recovered and 22% no response to traditional treatment (Hunduma, et al. [23]). To save their chicken during disease outbreak village poultry producer take different kind of measures like: use traditional medicine (33%), consult veterinarian (11.4%), call traditional healers (10.4%), sell the survived ones (4.5%). The wide use of traditional medicine was due to its low cost, local availability and easiness of application. Large flock sizes were obtained with those farmers that gave traditional medicine to their chickens. This indicates that traditional medicines do work and have the potential to improve the health status of village flocks. Hence, there is a need for research to determine their chemical properties, concentrations and mode of application (Matiwos, et al. [24]).

Vaccination: Vaccines are used to prevent or reduce problems that can occur when a poultry flock is exposed to field disease organisms. Vaccination has been considered the most effective means of controlling ND and has been used successfully throughout the world since the 1940s (Dias, et al. [25]). Vaccine quality is commonly blamed when a disease occurs; however, there are usually other factors responsible such as lack of a cold chain. A comprehensive investigation is often called for to identify the causes and to resolve the problem. In Ethiopia, two types of vaccines which have been used. These are: conventionally used vaccines which comprise: Hitchener B1(HB1) and LaSota live freeze-dried vaccines produced in 500 and 100 dose vials, produced by National Veterinary Institute (NVI), Bishoftu, Ethiopia and thermo stable vaccine (Wambura, et al. [26]). Village chicken vaccination particularly against NCD is more important than other management interventions; benefit-cost calculations done for the Tigray region of Ethiopia indicated that ND vaccination was more economically beneficial than the provision of daytime housing, supplementary feeding, cross breeding and control of broodiness (Udo, et al. [27]). In village production study in different parts of Ethiopia, no vaccination practice against poultry diseases was reported by (Moges, et al. [28]) and (Mengesha, et al. [29]). The finding of (Fisseha, et al. [30]) also indicated that the level of awareness about availability of vaccines for local chicken is low and the farmers do not have any experience of getting their chicken vaccinated against diseases. This is due to the fact that the farmers have no information about disease control and vaccination because of poor extension package of poultry production.

Constraints For Poultry Production

Indigenous chickens are good scavengers as well as foragers and have high levels of disease tolerance, possess good maternal qualities and are adapted to harsh conditions and poor quality feeds as compared to the exotic breeds. In Ethiopia, however, lack of knowledge about poultry production, limitation of feed resources, prevalence of diseases (Newcastle, Coccidiosis, etc.) as well as institutional and socio-economic constraints remains to be the major challenges in village-based chicken productions. According to (Tadelle, Ogle, et al. [31]), the primary problem cited by the village poultry farmers was high mortality of chicks. The major causes of this problem as perceived by the community and in their order of importance were disease (63.8 %), predation (21.8 %), lack of feed (9.5 %) and lack of information (4.9%), as per the reports of (Tadelle, et al. [32]). Insufficient water was also one of the causes of mortality in chicks and older birds and a contributing factor to low productivity. The major constraints of village indigenous chicken production were partly due to poor management of the chicken (prevailing diseases and predators, lack of proper health care, poor feeding and poor marketing information). On the other hand, attempt of replacing indigenous chickens by exotic chicken breeds was identified as a major threat in eroding and dilution of the indigenous chicken genetic resources (Hunduma, et al. [23]).

Disease: The major causes of death for village poultry production were commonly disease (mainly New Castle Diseases locally known as (“Fengil”), followed by predation. High incidence of chicken diseases, mainly Newcastle Disease (NCD), is the major and economically important constraint for village chicken production system (Fisseha et al., 2010). Mortality of village chicken due to disease outbreak is higher during the short rainy season, mainly in April (66.8%) and May (31.4%). Also, another reported that the NCD is one of the major infectious diseases affecting productivity and survival of village chicken in the central highlands of Ethiopia (Serkalem, et al. [33]). The major routes of contamination and spread of NCD from village to village are contact between chicken during scavenging and exchange of chicken from a flock where the disease is incubating and during marketing (Tadelle, Ogle, et al. [31]). Another study from Benishangul-Gumuz, Western Ethiopia done by (Alemayehu et al., 2015) reported that Newcastle disease were the most prevalent and economically important disease affecting chicken in the study areas mainly during the rainy season. Shortage of supplementing feeds during rainy season makes the chickens more vulnerable to diseases. In addition to Newcastle diseases, coccidiosis and fowl typhoid are the major cause for chicken mortality (Addis and Aschalew, et al. [34]). In Ethiopia seroprevalence surveys in village chickens have identified the presence of infectious bursal disease (Jenbreie, et al. [35]), salmonellosis (Berhe, et al. [36]), pasteurellosis and mycoplasma infection (Chaka, et al. [37]). Parasitic diseases, including coccidiosis (Luu, et al. [38]), helminthes (Molla, et al. [39]) and ectoparasites (Belihu, et al. [40]) have also been demonstrated to be highly prevalent in the country.

Predation: Predators were listed alongside diseases as major cause of premature death. The predation is strongly associated with the rainy season. The predators include primarily birds of prey such as vultures, which prey only on chicken and wild mammals such as cats and foxes, which prey on mature birds as well as chicks (Tadelle and Ogle, 2001). Predators such as birds of prey (locally known as “Culullee”) (34%), cats and dogs (16.3%) and wild animals (15%) were identified as the major causes of village poultry in rift valley of Oromia, Ethiopia (Hunduma, et al. [23]). Halima (2007) also reported that predation is one of the major constraints in village chicken production in northwest Ethiopia. Another study from Benishangul-Gumuz, Western Ethiopia done by (Alemayehu, et al. [41]) reported that wild cat (locally known as ‘shelemetmat’), eagle and foxes were the common chicken predators identified by the chicken owners in the study areas. Eagle is a serious problem in dry season while the rest are commonly attacking chicken during wet season. As reported by the chicken owners, in wet season the scavenging areas are covered by vegetation and this make a conducive environment for wild cat and foxes to attack chickens. In dry seasons, the vegetation of scavenging areas is less dense and chickens are vulnerable to eagles.

Feed Source and Lack of Proper Housing: In Ethiopia, village chicken production systems are usually kept under free range system and the major proportion of the feed is obtained through scavenging. The major components of Scavenging Feed Resource Base (SFRB) are believed to be insects, worms, seeds and plant materials, with very small amounts of grain and Table 1 leftover supplements from the household. Improving the diet of scavenging birds is difficult because it is not known what food they are eating (Smith, et al. [42]). The amount and availability per bird of this SFRB is significantly dependant on season, grain availability in the household, time of the grain sowing and harvest, and the biomass of the village flock. The limited capacity of the SFRB coupled with other factors; restricts the potential productivity of local birds to about 40 to 60 eggs per hen per year (Tadelle, Ogle, et al. [43]). However, unlike intensively kept poultry the scavenging birds are not in competition with humans for the same food and every egg or quantity of meat produced represents a net food increment. Any attempt at supplementation should take into consideration what the birds are actually eating (Smith, et al. [42]) and the proportion of the total diet scavenged by birds. In village chicken production, it is difficult to estimate the economic and/or physical value of feed resource input because there are no direct methods of estimating the scavenged feed input. According to (Hunduma et al. [23]) feed shortage mostly occurs from June to August time of the year for village poultry as it is not harvesting season of cereal crops.

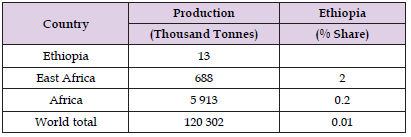

Table 1: Annual poultry meat production in Ethiopia as percentage share of African and global production, 2016.

Although no data are available about housing at national level, the local birds are set free on free range whereby they move freely during the day and spend the night in the main house. Overnight housing, perched in trees or on roofs and overnight housing within the main house are the common patterns of housing prevailing in the country. Lack of housing is one of the constraints of the village poultry production systems. In some African countries, a large proportion of village poultry mortality accounted due to nocturnal predators because of lack of proper housing (Dwinger, et al. [44]). Some research works also indicated that the mortality of scavenging birds reduced by improved housing. For instance, in the Gambia livestock improvement program, which included improved poultry housing resulted in lower chick mortality (19%) relative to that observed in Ethiopia (66%) and Tanzania (33%), where no housing improvements were made (Kitalyi, et al. [45]).

Lack of Organized Market and Poor Access to Main Market: Even though chicken meat is relatively cheap and affordable source of animal protein (Alemu, Tadelle, et al. [46]), lack of organized marketing system and the seasonal fluctuation of price are the main constraints of the poultry market in Ethiopia. Variation in price mainly attributed to high demand for chickens for Ethiopian New Year and holidays. It also partly influenced by weight, age of chickens and availability. The plumage color, sex, combs types, feather covers are also very important for influencing price. According to (Gausi, et al. [47]) the major constraints in rural chicken marketing were identified as low price, low marketable output and long distance to reliable markets. As a result, the smallholder farmers are not in a position to get the expected return from the sale of chickens. Likewise, poor marketing information system, poor access to terminal market, high price fluctuation and exchange based on plumage color, age and sex are among the main constraints of chicken market in the country (Kena, et al. [48]). Despite the benefits of village poultry keeping to poor households in most parts of the country, they face significant market constraints. The distance to the nearest market is a key factor; the nearer the market, the shorter the marketing chain and the higher the price received for both live birds and eggs. It is also clear that increased involvement of intermediaries leads to reduced prices for the producer. A price reduction of 68% for birds and 25% for eggs was observed in areas with poor market access in Tigray Regional State compared to those areas with better market access.

Transaction costs may be reduced through improving access to information, infrastructure and organization of the poultry producers. However, the costs of transport, credit and marketing risks should be carefully assessed (Aklilu, et al. [3]). A further constraint to the marketing of traditional household poultry and products is the fact that there is no packaging and weight standardization of market eggs and that traditional storage method can lead to deterioration of the quality of Table 2 eggs. According to (Gausi, et al. [47]), small holder village chicken producers tend to ignore new technology even when it appears to be better than their current practices due to market limitations.

Replacement of Indigenous chickens by Exotic Chicken Breeds: The local chicken genetic resources in the Amhara region of Northwest Ethiopia were seriously endangered owing to the high rate of genetic erosion due to the extensive and random distribution of exotic breeds, by both governmental and non-governmental organizations, since they are believed to dilute the take different kind of indigenous genetic stock. This threat is also in line with the food and agriculture organization(FAO) report Replacement of indigenous chickens by exotic chicken, which states that animal genetic resources in developing countries in general, are being eroded through the rapid transformation of the agricultural system, in which the main cause of the loss of indigenous animal genetic resources is the indiscriminate introduction of exotic genetic resources, before proper characterization utilization and conservation of indigenous genetic resources FAO et al.[49].

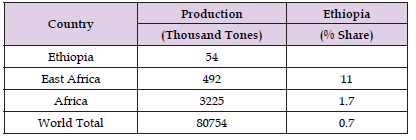

Table 2: Annual poultry egg production in Ethiopia as percentage share of African and global production, 2016.

Poultry production and productivity is playing an important role in increasing the socio-economic status of rural community and employment in rural areas. However, the village chickens suffer low productivity and high mortality. The limited biosecurity measures in the poultry production system, where almost every household in rural areas practice backyard poultry and commonly live with their poultry in the same house or in an attachment where there is no barrier the potential for becoming in contact with infected poultry droppings and corpses, which are major sources of infection, is very high. Disease control and improved management village chicken production are lacking in the country. Diseases followed by predation are found to be the major constraint of chicken production and productivity particularly in rural area of the country which needs systematic ways of mitigating them [50-53].

Based on the above conclusion, the following recommendations are forwarded:

• There should be appropriate intervention in disease and Predator control activities so as to reduce chicken mortality and improve productivity.

• Control of diseases should be achieved through vaccination and improvement in veterinary and advisory services.

• Efforts to increase productivity through improvements in health, feeding, housing, and daily management should be encouraged as they will result in increased economic returns.

• Training for both farmers and extension staff focusing on disease control, improved housing, and feeding, marketing systems could help to improve productivity of local chicken.