Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Ousmane Diaby1*, Clarence Mbanga2, Ngassa B Andinwoh2 and Yauba Saidu2,3

Received: August 05, 2024; Published: August 14, 2024

*Corresponding author: Ousmane Diaby, Department of Public Economics, University of Yaoundé 2 Soa, Cameroon

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.58.009121

Background: The World Health Organization estimates that annually, about 150 million people experience severe (catastrophic) financial difficulties because of healthcare payments. This burden is greater in low- and middle-income countries, where inequalities in access to health care increases the vulnerability to catastrophic health expenditure (CHE). This is the case of Cameroon, that records the highest out-of-pocket health care payments in Africa. The current study sought to examine the interpretation of the concept of CHE across theoretical and empirical literature, and to assess the factors associated with increased household vulnerability to CHE in the Cameroonian context.

Methods: This was a two-pronged study which involved:

1. A synthesis of published literature on the conceptualization of CHE and

2. A cross-sectional analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data obtained from a survey of 5019 households across all ten regions of Cameroon (sampled using multistage randomized cluster sampling), conducted by the Cameroon Ministry of Public Health in July 2020. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated to increased household vulnerability to CHE.

Results: The findings of this study reveal that 32.8% of Cameroonian households are vulnerable to CHE. This vulnerability is influenced by various socioeconomic and demographic factors such as gender, level of education, income level and marital status. Specifically, male-headed households showed greater vulnerability to CHE than female-headed households, while households that utilized traditional medicine and those polygamous, high earning, highly educated (upper secondary and tertiary) heads, and heads working in the informal non-agricultural sector, showed less vulnerability to CHE.

Conclusions: A considerable proportion of Cameroonian households are vulnerable to CHE. The socioeconomic and demographic factors that influence vulnerability to CHE suggest the need for effective social policies that regulate the alternative healthcare sector (which consist mainly of traditional medicine and self-medication), as well as the need to prioritize vulnerable groups (formal primary sector workers and young people) as the country implements its universal health coverage system.

Keywords: Catastrophic Health Expenditure; Factors; Households; Cameroon

Abbreviations: CHE: Catastrophic Health Expenditure; WHO: World Health Organization; UHC: Universal Health Coverage

Health expenditures that absorb resources reserved for other consumption items are referred to as Catastrophic Health Expenditure (CHE) [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines a health expenditure as catastrophic when the direct health payments made by a household exceeds 40% of the household’s capacity to pay, following the calculation algorithm proposed by Xu, et al. [2]. Indeed, the WHO estimated that 150 million people face catastrophic healthcare costs each year because they pay directly for healthcare out of pocket, and that 100 million are pushed into poverty each year due to catastrophic healthcare costs [3]. In addition, the WHO reported that between 2000 and 2017, the number of people financially devastated by health expenditures increased from 630 million to 1.125 billion. These people can be found in both developed and developing countries. In developing countries, inequalities in access to health care increases the vulnerability to catastrophic health expenditure (CHE), evident from the catastrophic healthcare costs incurred by the poor, and has become the subject of a vast body of empirical literature. There are two main schools of thought in this extensive body of literature: one which focuses on the measurement of CHE, and the other which focuses on the factors that predispose households to CHE, a body of literature that has considerably grown over the past decade. Regarding the measurement of CHE, a variety of approaches have been proposed by O’Donnell, et al. [4], who will be covered in more detail in the literature section of the paper.

With respect to the factors that explain household vulnerability to CHE, all available work is grounded on household poverty as it relates to income and other socioeconomic factors. Evidence from this literature suggest that household income is one of the major factors associated with CHE. In addition to income, other characteristics, such as the occupation of the household head, area of residence, household size, and level of education of the household head, have equally been identified in literature as factors that predispose households to CHE [5-11]. However, the extensive empirical literature typically neglects to consider cultural factors when investigating the determinants of households' susceptibility to CHE. Specifically, traditional medicine is still not considered in these studies, even though the recent COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that traditional medicine, in some contexts, can provide effective healthcare for households at minimal cost. In Cameroon, social protection policies have evolved with the economic and social transformations of the 19th century, which were marked by the return of a welfare state centered on initiatives to combat poverty and prevent health issues. Insurance and assistance mechanisms are still in their infancy, resulting in the pre-eminence of direct payment for health care, which remains one of the most inefficient and inequitable ways of financing a health system [12], and could be an important contributing source of poverty [13].

Faced with this worrying situation, public authorities have implemented public policies to reduce the financial burden related to health expenditure. These policies include, but are not limited to, free vaccines for children aged 0-18 months, free care and treatment for people living with HIV/AIDS, and subsidies for the treatment of certain chronic diseases such as renal failure and viral hepatitis. Despite these interventions, a considerable gap still needs to be filled to protect Cameroonian households from CHE. In effect, according to the 2019 Cameroon Demographic and Health Survey, the expected results of policies intended to reduce the health bill are mixed, as only 29.1% of the Cameroonian population has access to formal health care. The remaining population turns to informal care (self-medication and/or traditional medicine), making it difficult for social protection instruments to have full societal impact. In fact, 70% of direct payments for health care in Cameroon are borne by households, far above the average for countries with the same level of income (69.1% in Nigeria, 63.5% in Togo, 35.6% in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), 27% in Gambia and 24.2% in Rwanda). About 53.4% of these direct payments for health come from the earnings of family members, 25.4% from savings, 16.1% from the sale of property or assets, and 11.9% from loans.

Limited evidence exists on the burden of chronic health expenditures (CHE) in Cameroon, with Owoundi [14] being the sole researcher to offer a preliminary assessment on the issue, highlighting increased poverty risk due to CHE among households with aging, uneducated, poor members, or those working in informal agriculture or rural areas. However, households’ behavioural approach concerning their therapeutic habits such as self-medication and the use of unconventional treatment practices like traditional medicine were not considered. To bridge this gap, we undertook a research work with two key objectives: first, to examine the interpretation of the concept of CHE in theoretical and empirical literature, and second, to determine the socioeconomic and demographic factors (including modifiable health behaviours such as self-medication and traditional medicine use) that predispose Cameroonian households to CHE. By including health behaviours such as traditional medicine, that have not been explored in the available literature on CHE, this research would contribute to the existing body of knowledge on CHE and inform the identification of effective health financing policies and the formulation of public policies on access to health care.

This study was conducted using a two-pronged approach that involved;

1. A literature review synthesizing published literature on the conceptualization of CHE,

2. A cross-sectional analysis of data obtained from a survey of households across all ten regions of Cameroon, conducted by the Cameroon Ministry of Public Health in July 2020.

Literature Review

Database Search: We searched PubMed, Science Direct and Wiley Online Library for articles on the concept of CHE using the following keywords: catastrophic spending, consumer spending, and health care service utilization. We also combined these keywords to limit the number of articles found. The terms households, affordability and poverty were added to narrow down the search. In addition, four books on public health were searched to document the notion of access to healthcare. The reference list of retrieved articles and book chapters were cross-referenced to highlight the most frequently cited. Finally, manuscripts on CHE were retrieved directly from the web through Google. Citations referring to an already published manuscript were not retained for the analyses.

Theoretical Foundations: There are several theories that explain the use of or demand for healthcare, particularly health expenditures [15]. The framework for our analysis was the neoclassical approach. According to neoclassical theory, the analysis of healthcare demand and consumption is based on the utility function of the consumer (patient). The assumption is the rationality of the patient, whose choices and preferences are shown to be constant over time [16]. The patient therefore seeks to maximize his/her utility (satisfaction induced by the consumption of care under the constraint of his/her income) considering the price of health goods and services in an environment without uncertainty. Arrow [17] was the first health economist to question the fundamental assumptions of the neoclassical consumer theory, highlighting the complexity of good health and the dysfunctions that characterize the healthcare market, due to informational asymmetries and demand uncertainty. Grossman [18] build on Arrow’s work by incorporating rational economic calculations based on the principles of the human capital theory, in his analysis of healthcare demand [19]. By so doing, Grossman laid the foundation for modelling the demand for care by providing further clarity to Arrow’s concept of health demand. This distinction emphasized that health had only a use value, while healthcare had an exchange value [20]. Grossman’s contribution comprises two main models. Firstly, he presents a consumption function model that values the enhancement of health status based on the well-being it brings.

Secondly, he introduces an investment function model that demonstrates how the improvement in health status enhances individuals' work capacity, income, and overall consumption capacity. Grossman’s model stands out from other primary models of medical care consumption, due to its noticeable emphasis of health status as an endogenous variable that depreciates over the course of an individual’s life cycle and evolves based on the patient’s preferences. Grossman’s model on the demand for care therefore has the merit of clearly linking the consumption of care with economic variables such as income and the price of care. Nevertheless, the main criticism of his models remains the insufficient explanatory power of economic factors alone in capturing the complex dynamics of health care utilization, as non-economic factors such as demographic, social, cultural, contextual, and organizational factors of the health system, play crucial roles in shaping healthcare consumption patterns. It is highly recommended that these non-economic factors be considered, as they contribute to the diverse range of lifestyles and health practices observed across different geographic locations and the environments. The behavioural model of Andersen and Newman [21], bridges the gap by providing a strong theoretical basis for explaining healthcare consumption by integrating various factors beyond just economic and preference factors.

These factors can be broken down into three groups of variables, notably demographic variables, which include the gender, age, household size and marital status of the household head; household social variables, which refer to the educational level, occupation, social class, race, and ethnicity of the household head [22]; and finally, variables relating to health beliefs. Andersen [23] highlights that certain demographic variable, such as older age and female gender of household members, positively influence health service utilization, while other factors have less influence. Additionally, he concludes that individuals’ perception of their health status is influenced by their cultural context and their personal evaluation of the importance of their health. With the considerable technological advances in modern medicine, economic theory has not fully elucidated the link between the demand for healthcare and economic factors such as income and the price of care. Conversely, as technical projects are not equally distributed, they have often led to greater inequalities in access to healthcare [24]. The latest example is the COVID-19 vaccine; its unavailability in many developing countries has indirectly contributed to the spread of the pandemic.

Nevertheless, the literature is consistent in stating that improvements in living standards tend to stimulate demand for healthcare and health services [25]. However, researchers have been slow to take an interest in the issue of the burden of health expenditure, which emerged in 2015 under the aegis of the WHO as a criterion for assessing access to healthcare and for evaluating, among other things, health systems at the global level. In sum, while various theoretical works have conceptualized the demand for health care and the constraints on access to it, there has been a lack of specific theoretical discussions on the conceptualization of catastrophic health expenditure. However, various empirical studies have been conducted in relation to different approaches to understanding catastrophic health expenditure.

Empirical Foundations

Measures of CHE: The empirical literature has utilized three approaches, as proposed by O’Donnell, et al. [4], to assess CHE, albeit with different thresholds. The first approach, known as the income approach, assesses CHE based on household income. However, according to O’Donnell, et al. [4], using income alone does not provide a very sensitive measure. For instance, two households with the same income and health expenditures, may have different financial capabilities, in the sense where the first household may have the savings to finance its health expenditures, while the second may be forced to reduce its current household consumption to finance these costs. This difference does not reflect in the ratio of health expenditure to income, whereas in reality, the burden is higher for the household with no savings. Thus, health expenditure is more catastrophic for a household without savings [26]. The discrepancy can be revealed if total household expenditure is used as benchmark as opposed to income. The second approach, the total household consumption expenditure approach, implicitly assumes that CHE is defined in terms of the proportion of healthcare payments in relation to total household consumption expenditure. The problem with this approach, however, is that health expenditure as compared to other consumption expenditures, may be insignificant or null for very poor households in low-income countries [4]. The insignificance is particularly pronounced for such households because most of the household resources are absorbed by other expenditures such as food, which are considered essential.

Consequently, the impact of health expenditure is disregarded for households that lack the financial capacity to afford healthcare expenses. To address this issue, O’Donnell, et al. [4] proposed an alternative solution, which involves assessing CHE not in terms of the share of health expenditure within the household budget, but rather by considering the net necessities of other expenditures. The third approach involves deducting all other expenditures from expenses intended for basic needs, with the latter described by Wagstaff and Van Doorslaer [27] as non-discretionary expenditure. The challenge, however, lies in determining which items could be classified as discretionary expenditure. In addition, the WHO recommends the use of non-food expenditure as a measure of a household’s ability to pay, which is used as a denominator for disaster assessment [12]. Using non-food expenditure is deemed appropriate because food is considered a basic necessity and represents a significant portion of household expenditure. In the case where the denominator used to assess household vulnerability to CHE is household income, Amaya-Lara defines household facing CHE as those whose health expenditure exceeds 20% of the total household income [28]. However, when the denominator is relative to total household expenditure, the threshold generally used is 10% [29-31].

This threshold is generally regarded as the point at which the household is compelled to sacrifice other basic needs or incur debt to finance healthcare expenditure. In the last approach (used by the WHO) where health expenditure is expressed as a percentage of non-food expenditure (ability to pay), the threshold considered is generally 40% [32-34]. However, other studies have considered variations of this threshold, typically 10%, 15%, 25% and 40%, to account for the sensitivity of the measure [35,36].

Factors Associated with CHE

Household income level emerges as the primary determinant of vulnerability to CHE. Previous research has demonstrated that, low-income status is a major deterrent to enrolment in healthcare insurance schemes given the cost of individual contributions, which compels such households to bear the full cost of healthcare expenditures on their own. [5-7,37-42]. Studies by Shi, et al. [33] suggest that households with; low per capita incomes, household members who are elderly, hospitalized, or chronically ill; and unemployed household heads, are more likely to experience CHE and impoverishment due to healthcare expenses. In terms of household income, Masiye, et al. [26] found a high prevalence of CHE among the poorest segments of the Zambian population. Several empirical studies have underscored the role of economic and socioeconomic factors in rendering households vulnerable to CHE, collectively establishing that insufficient financial resources serve as the principal contributor to a household’s susceptibility to CHE [5,7,33,39,43,44]. Furthermore, it has been observed that households with higher income generally consider the individual contributions for health insurance schemes to be more affordable in comparison to the expenses of the care itself [39-41,45]. In this regard, Jütting [7] highlights that the participation of the poorest households in mutual health insurance schemes is relatively low compared to more affluent households.

Consequently, the poorest households bear the costs of healthcare themselves, which makes them more vulnerable to CHE. However, Criel [44] notes that both poor and well-off households in the community are well represented among those who pay for their health care. There are two plausible explanations for the presence of wealthier households among those who do not participate in insurance schemes. Firstly, individuals who are better off are likely to be less apprehensive about their future ability to bear the cost of healthcare without mutual membership. Secondly, these households may also have reservations about fully engaging in a system where some less well-off members struggle to pay their contributions regularly. As a result, even richer households may bear the financial burden of their care and therefore be likely to become vulnerable to CHE. Additional demographic factors shown to influence the vulnerability of households to CHE include: area of residence [10,46-48], occupation of the household head [49], gender [9,50,51], educational attainment [51], household member aged 65 and over [11,53-55], household member aged under 15 years, and household standard of living [52-56].Findings from the study conducted by Xu et al suggest that the area of residence (urban or rural) has a significant impact on the likelihood of households being vulnerable to CHE [8]. However, Su, et al. [57] found no significant effect of residence on CHE. A study by Olumide [58] found that older, poorer, and smaller households were more vulnerable to CHE.

These findings were supported by those from other studies conducted by Krutilova and Yaya [59,60], and Agyemang, et al. [11]. On the other hand, Atake [34], found no association between the age of the household head and CHE. Similarly, Witter et al. [61-64] concluded that female-headed households exhibited less vulnerability to CHE as compared to male-headed households. Regarding household size, several empirical studies have examined the relationship between household size and vulnerability to CHE. Findings from works by Xu, et al. [8,57,64], indicate that households consisting of nuclear family members of the household head are more susceptible to CHE compared to larger families. One possible explanation, as suggested by Amaya-Lara [28], is that large families tend to have more members, including those in the under-5 and over-65 age groups. Furthermore, the presence of economically active members in the household has been found to reduce the likelihood of the household incurring CHE. However, it is worth noting that Sanoussi and Ametogolo [65], argue that a higher level of education of the head of household and the use of health promotion tools (such as treated bed nets) are associated with a greater vulnerability to CHE.

While the existing literature has explored various factors related to CHE, certain sociological factors have yet to be fully considered. In Cameroon, for instance, it may be relevant to consider religious affiliation and geographical location as determinants of the level of CHE, as these elements could influence the health behaviour of individuals. We sought to bridge this gap by undertaking the cross-sectional analysis outlined below:

Cross Sectional Analysis

We conducted a cross sectional, secondary analysis of data obtained from a survey on the knowledge and perception of universal health coverage in Cameroon, conducted by the Ministry of Public Health in July 2020, using a sample of 5,019 households selected from across all ten regions of Cameron (representing the demographic and socioeconomic diversity of the Cameroonian population). The detailed survey methodology has been comprehensively described elsewhere (ref).

Presentation of Variables

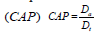

Dependent Variable: To measure CHE, the first step is to extract expenditure on food (Da) from the total household expenditure (Dt) to obtain the ability of households to pay for care

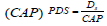

The second step is to determine the burden of healthcare expenditures by relating healthcare expenditures (PDS)to the ability to pay for health care

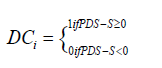

The third step is to define a thresholdS, which represents the pre-defined limit for CHE based on data from existing literature (40% for this study).

The measurement of CHE (DCi) is obtained by comparing the burden of health expenditure with the selected threshold. If the burden of healthcare expenditure exceeds the defined threshold, the household is assigned the value of one (01), indicating vulnerability to CHE. On the other hand, if the burden of health care expenditure is below the defined threshold, the household is assigned a value of zero (00), indicating no vulnerability to CHE.

The impact I of catastrophic expenses is as follows:

In line with the approach used by Xu, et al. [32], we considered health expenditure as catastrophic if direct payments made by households exceeded 40% of their ability to pay (total household expenditure minus the poverty line or food expenditure). Thus, all households with a health expenditure to total expenditure ratio (net of food expenditure) greater than 40% were considered vulnerable to CHE. This criterion was chosen due to the significant portion of the population being employed in the informal sector, where income levels are difficult to accurately measure.

Explanatory Variables

In this analysis, the socioeconomic and demographic factors of Cameroonian households that explain their vulnerability to catastrophic expenditure are presented. The socioeconomic factors are mainly gender, age, education, marital status, treatment practices and income. The demographic factors include distance to the nearest health facility. This analysis provides a plausible view of the behaviour of Cameroonian households, as we utilize a representative sample of the national population in this study.

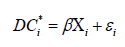

Choice and Rationale of the Estimation Method: The analysis of determinants of household vulnerability to CHE in this study aligns with Grossman’s theory of health demand [18]. According to this theory, all individuals are born with an initial stock of health capital that depreciates with age but can be preserved through investment in healthcare. Households, therefore, become vulnerable to CHE by investing in healthcare through out-of-pocket payments. To assess the determinants of household vulnerability to CHE, we employed a binomial logit model. The choice of this model was based on two key reasons. First, logit models are ideal for unordered or binary items, as is the case with the dependent variable (CHE), which takes two distinct values: households with catastrophic expenditure (value of 1) and households without catastrophic expenditure (value of 0). The second reason is the similarity between our study and those in literature that have equally employed logit models for such analysis [8,34,57,61-65].

The equation used to model a household’s vulnerability to CHE is as follows:

CHE =1 if the household faces catastrophic expenditures

CHE= 0, otherwise

Descriptive Statistics

Overall, 32.8% (XX/5,019) of surveyed households were vulnerable to catastrophic expenditure. Table 1 highlights the sociodemographic characteristics of surveyed households, with respect to their vulnerability to CHE.

Note: *** Significance of the chi-square test at the 1% threshold.

Economic Characteristics of Households and Vulnerability to CHE

Vulnerability to CHE significantly decreased with income level, with a lower proportion (14%) of households whose heads earned US$ 244.4 or more being vulnerable to CHE as opposed to 64% of households whose heads had an income of < $81.5 (Table 1). Similarly, a significantly greater share of households who recorded lesser expenditure on food, were less vulnerable to CHE as compared to those spending more. The proportion of households vulnerable to CHE was equally significantly higher among households with heads working in socio-professional categories that usually have less income (e.g. students, apprentice) (41.1% and 45.2%, respectively) as compared to those whose heads worked in higher paying socio-professional categories such as self-employed individuals (34.6%). The sector of activity of the household head equally showed a significant relationship with vulnerability to CHE, with a greater proportion of households (41.8%) with heads worked in the primary sector (e.g. agriculture, livestock etc.) being more vulnerable to CHE as compared to households with head working in other sectors (Table 1).

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Households and Vulnerability to CHE

Several social, demographic, and geographic characteristics showed a significant relationship with vulnerability to CHE. Regarding age, a greater proportion of households with young heads (42.1%) and those with older heads (39.4%) were vulnerable to CHE compared to those with heads of intermediate ages (31.8%) (Table 1). In total, 42.1% and 39.4% of households with heads in the [66,16-25] and 55+ age groups, respectively, were vulnerable to CHE, as opposed to 31.8% of households with heads in the 25-55 age group (Table 1). With respect to marital status, a greater proportion of households whose heads were single (40%) and widowed (39%), were significantly more likely to be vulnerable to CHE. We equally noted that a significantly higher proportion of households with heads being separated/divorced (100%), widowed (77.3%), in polygamous marriages (73.7%), who had an income of < US$ 81.5 were significantly more vulnerable to CHE (Table 1). No household with an income of more than US$ 81.5, regardless of the marital status of the household head, was vulnerable to CHE. The interplay between household income, the marital status of the household head and vulnerability to CHE is further highlighted in Table 2.

We found no significant difference in the proportion of households vulnerable to CHE with regards to the sex of the household head. A greater proportion of households with Muslim heads (36.6%) were significantly more vulnerable to CHE as opposed to other religions (Table 1). In total, 51% of household heads with higher levels of education are vulnerable to catastrophic expenditure. The next highest vulnerability rate is for those with no education at all, at 42.5%. Moreover, it appears that among heads of households with a higher level of education, most are vulnerable to catastrophic expenditures. The same is true for those without an educational certificate. No trend was observed in the relationship between the household distance from the nearest health facility and CHE (Table 1).

Factors Associated with Household Vulnerability to CHE

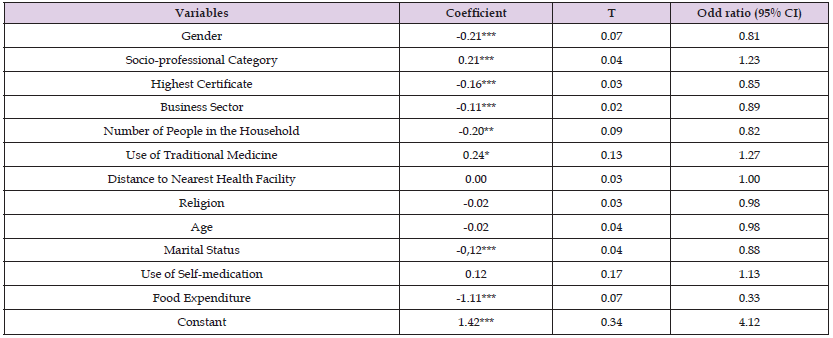

Table 3 presents results from the logistic regression outlining factors associated with household vulnerability to CHE. XX. The regression model used explained 8.7% of the variability observed in the dependent variable (R = 0.087), and correctly predicted 68% of the answers sought. The robustness of the regression analysis and consequently the accuracy of the results it generated was ascertained through pre- and post-estimation validity tests. The likelihood ratio test assessing model fit revealed a significant improvement over the baseline model (c² = 563.41; p<0.01) suggesting that the predictor variables used enhanced the model fit. In addition, the Hosmer and Lemeshow test (c² (8) = 6.24) yielded a non-significant result (c² (8) = 6.24), indicating that the model adequately captured the relationship between the predictors and the outcome variable (household vulnerability to CHE).

Table 3: Household characteristics associated with increased vulnerability to Catastrophic Health Expenditure in Cameroon.

Note: * **p<0.01 **p<0.05 *p<0.1

Our study sought to examine the interpretation of the concept of CHE in theoretical and empirical literature, and leverage this as hypothesis to determine the socioeconomic and demographic factors (including modifiable health behaviours such as self-medication and traditional medicine use) that predispose Cameroonian households to CHE. Our results suggest that female headed households are less vulnerable to CHE than male headed households. This observation could be attributed to the dynamics of households in Cameroon, where men are typically assigned greater responsibility and are generally responsible for the welfare of the household, with their income serving as a crucial source of support for the entire household. In this study, it was found that nearly 1,000 male-headed households were vulnerable to CHE, whereas only 649 female-headed households face the same vulnerability (Table 3). These findings are consistent with those obtained by Akinkugbe [67] in Botswana, which indicated that female-headed households are less vulnerable to CHE. Additionally, Ukwaja, et al. [68] found that that male-headed household in Nigeria were more vulnerable to CHE due to their high levels of responsibility. It is, however, important to note that these results are in contrast with those of several other empirical studies [8,58,59,65,69-71].

For instance, Beaulière et al. in Côte d’Ivoire [72], observed that female-headed households living with HIV were more vulnerable to CHE, while Mondal, et al. [67], found that the gender of the household head is not a significant factor in the household’s vulnerability to CHE in low-income countries. We also found that household income was positively associated with vulnerability to CHE, with households having a high standard of living (as identified by the income of the household head) being less vulnerable to CHE and vice versa. In effect, we found that households whose heads earned below US$ 81.5 demonstrated a greater vulnerability to CHE relatively to higher earning households. The vulnerability to CHE progressively decreased, with increasing household income. The rationale behind this relationship lies in the ability of higher income households to readily afford all other expenses, including those for healthcare (medication, clinical examinations, and hospitalization). In addition, to having a high standard of living, household heads in this category often have to support multiple family members and therefore usually invest in health insurance to manage healthcare needs. This is in line with findings obtained by Su, et al. [73,26]. Moreover, households with high income tend to consume more nutritious foods, which contributes to preventing vulnerability to certain diseases that could lead to CHE.

However, McElroy, et al. [74] found that the household head being self-employed or working as a government employee are factors that contribute to their households being more vulnerable to CHE. Furthermore, households with smaller incomes allocate a larger portion of their income on food [75]. Consequently, the smallamount of income directed towards health care remains insufficient to satisfy their needs, rendering them more vulnerable to CHE.Another key finding from our study was the tendency for households with heads having a high level of education (upper secondary and tertiary) to be protected from CHE. This could be explained by the fact that educated household heads typically have access to stable and decent employment and hence a substantial income that can cover household expenses without the risk of incurring catastrophic expenses. Moreover, their education level acts as a protective factor against various health risk and pathologies, as they tend to exhibit better control over their nutrition, which not only reduces vulnerability to chronic diseases but also minimizes their exposure to contagious diseases. This is consistent with findings obtained by Sanoussi and Ametogolo [65], who found that households with highly educated heads were less vulnerable to CHE. In contrast, less educated household heads are usually resident in rural areas, which typically lack adequate access to health care services. As a result, they face greater challenges in meeting their healthcare needs and are more susceptible to catastrophic expenses.

The socio-professional category and sector of activity of the household head was also found to be associated with the households’ vulnerability to CHE. We found that households whose heads worked in the primary sector, were more vulnerable to CHE compared to households whose heads worked in the informal sector. This could be explained by the intricate relationship that exist between the sector of activity and income. In effect, individuals working in the primary sector are typically involved in activities such as agriculture and livestock, which typically offer lower wages and income compared to informal activities and formal sector jobs, with lower income previously highlighted as being a factor that significantly increases vulnerability to CHE. These results align with those of Akinkugbe [67,76,77], in Botswana, Tanzania, and Kenya, respectively, who indicate that working-class household heads have a high probability of vulnerability to catastrophic expenditure. On the other hand, studies have highlighted that informal sector workers who are generally self-employed, tend to enjoy higher incomes and are relatively more protected against CHE [78]. The use of traditional medicine was found to limit household vulnerability to CHE. This can be attributed to the fact that self-medication reduces reliance on modern healthcare, resulting in lower expenditure.

This finding highlights the significance and importance of traditional medicine in Cameroon and could be explained by the fact that high travel costs to nearby health facilities, lower income, and lower quality of care in rural hospitals encourage the practice of traditional medicine [27]. These findings are in line with those of Schneider [6,42,43,79,80], who suggest that individuals often resort to traditional medicine due to dissatisfaction with the quality of formal healthcare, especially in public health facilities. As a result, people only tend to seek formal health care in emergency situations, resulting in a reduced rate of consultations at health facilities. The marital status of the household head was equally associated with vulnerability to CHE, with polygamous households being less likely to CHE as compared to monogamous households. This finding could be explained by several factors, including the higher incomes typically observed in polygamous households. In economic theory, a polygamous household can be viewed as a collective household, as opposed to a monogamous household, which can be seen as a unitary household. In a collective household, such as a polygamous household, decision-making is decentralized, as there are multiple decision-making centers, notably the husband and his wives.

This decentralization extends to the financing of the household's health expenses, as they are not solely the responsibility of the husband but are also shared by his wives who engage in income-generating activities. This collective approach to decision-making and income generation within polygamous households can contribute to a more diversified and robust financial situation, reducing the risk of incurring catastrophic expenses. However, it is important to note that the specific dynamics and financial arrangements within polygamous households can vary and may not apply universally. Overall, the decentralized financing of health expenses in polygamous households, with contributions from multiple income-generating members, can serve as a protective factor against CHE. Our study equally revealed that the size of the household was associated with the occurrence of CHE. Generally, households with a greater number of individuals within the household were more vulnerable CHE. These findings are in line with the conclusions reached by previous studies conducted by various researchers [69,74,78,79]. This relationship is particularly influenced by the presence of elderly persons in the household. Ezzrari and Fellousse [55] provide evidence supporting the fact that households with at least one person aged 65 and over face a greater risk of CHE. This is mainly due to the increased likelihood of costly chronic among elderly individuals. In contrast, households that have at least one child under the age of five tend to be less vulnerable to CHE.

Lastly but not the least, we observed food expenditures to be associated with CHE. These expenditures are indirectly related to household income, although income itself may be small. Households with lower incomes allocate a greater proportion of their income/resources to food [74]. This leaves a little and typically insufficient proportion of the said income directed towards healthcare, rendering them more vulnerable to CHE [81,82].

The findings of this study reveal that 32.8% of Cameroonian households are vulnerable to CHE. This vulnerability is influenced by various socioeconomic and demographic factors such as gender, level of education, income level and marital status. Specifically, male-headed households showed greater vulnerability to CHE than female-headed households, while households that utilized traditional medicine and those polygamous, high earning, highly educated (upper secondary and tertiary) heads, and heads working in the informal non-agricultural sector, showed less vulnerability to CHE. These findings suggest the need for effective social policies that regulate the alternative healthcare sector, which consist mainly of traditional medicine and self-medication. Furthermore, the establishment of a universal health coverage should prioritize formal primary sector workers and young people, who constitute a rather vulnerable group.

The opinions stated in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official stance of their respective institutions or the funder of the study.

XX.