Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Rejula Fathima1*, Gibi Paul2, Pratheek VS3, Vidya K G4 and Mridula Parameswaran5

Received: July 21, 2024; Published: August 05, 2024

*Corresponding author: Rejula F, MDS Associate professor, Department of Conservative Dentistry, GDC, Trivandrum, India

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.58.009090

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic caused severe stress among dental professionals and students.

Aim: To assess the perceived stress levels and strategies for coping with stress among clinical dental undergraduates of Kerala all along the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of the perceived stress scale-10 and Brief- COPE scale.

Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted among the third and final year BDS students of dental colleges under the Kerala University of Health Sciences through an online questionnaire using PSS-10 scale and Brief COPE Scale for six months. Comparison of continuous variables between two groups was analyzed by student t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. Association between qualitative variables was analyzed by the Chi-square test. The relationship between quantitative variables was analyzed by Pearson correlation.

Results: Assessment of overall mean scores of various sub-domains revealed maximum mean score for the use of informational support (5.42±1.50) followed by positive refraining (4.52±1.45). For emotion focussed coping, the maximum mean score was reported for humour (5.54±1.51), and the least mean score was reported for acceptance (4.04±1.63). The overall mean scores of Adaptive Coping and its dimensions were higher among females and among participants diagnosed with psychological or psychiatric disease in the past. Participants who had been diagnosed with psychological or psychiatric disease in the past had a higher total PSS mean score (23.91 ± 7.39) compared to other participants (19.94 ± 6.93), and this difference was significant (p=0.02). With respect to adaptive coping strategies, a statistically significant difference was observed based on the year of study for dimensions “positive reframing” (p = 0.036) and “instrumental support” (p = 0.012), with a higher overall mean score among third-year participants (39.42±6.20). In terms of adaptive coping strategies, a statistically significant difference was observed based on socio-economic status for dimensions “humour” (p = 0.031) and “acceptance” (p = 0.029). Pearson’s correlation analysis was done between coping strategies and PSS scores. A significant positive correlation with perceived stress score was recorded for adaptive coping strategies. There was a statistically significant positive correlation between emotional support (0.308), planning (.238), denial (.218), and acceptance (.135) with a PSS score while there was a statistically significant negative correlation between substance use (-.204), positive reframing (-.141), and use of informational support (-.105) with a PSS score.

Conclusion: The current study showed that females, day scholar students, and final year part-2 dental students reported significantly higher levels of perceived stress. The majority of students have been using adaptive coping techniques to combat stress. It is important to inform students about stress’s psychological symptoms and indicators. Moreover, stress avoidance and management measures should be incorporated into the dental curriculum to promote students’ well-being.

Keywords: Perceived Stress Levels; Coping Strategies; Stress; Dental Undergraduates; Kerala; Pandemic; COVID- 2019

A highly infectious coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been the utmost public health challenge throughout the globe (Raja, et al. [1]). This pandemic severely impacted health and social activities worldwide and the economy (Chang, et al. [2]). The world health organization (WHO) announced that the COVID-19 outburst had created a health crisis among citizens of multinational concern (Klaassen, et al. [3]). The mode of transmission of this viral infection is not only through direct contact but also can spread by aerosol. To limit the spread of infection, the governments of various nations were compelled to implement social distancing, lockdown, quarantine or isolation policies, and closure of educational institutions and workplaces as a final course of action (Chang, et al. [2-3]). Students pursuing higher education, especially those related to health sciences, are stressed. Unfortunately, dental school undergraduates are comparatively more stressed than the general population due to the highly demanding undergraduate study program and stressful learning environment (Halboub, et al. [4]). Literature highlights that stress is significantly prevalent among dental graduates (Klaassen, et al. [3]). In addition, dental undergraduates are at higher risk of contracting and transmitting the disease as they are exposed to aerosols and infected droplets from patients’ oral cavities (Raja, et al. [1-2]). These circumstances were mentally exhausting for dental undergraduate and postgraduates, faculty, and practitioners. Moreover, online teaching, uncertainty in graduation finishing date, lack of required clinical experiences, inadequate critical training and exposure to examinations, travel restrictions, and fear of mortality led to emotional stress apart from already existing academic and professional stress in the dental professionals (Raja, et al. [1-3]).The COVID-19 pandemic has made it necessary for universities to assess the degree of stress among dental professionals to provide appropriate counselling and assistance for mental well-being (Raja, et al. [1]). Numerous investigations have evaluated perceived sources of stress among dental professionals and noted the following potential stressors: elaborate clinical procedures which are difficult to learn, workload, inability to finish the clinical quota, information overload, strive to achieve precision, series of formative and summative assessments, the pressure of scoring, receiving criticism, inconsistency of feedback, dealing with difficult patients, and inappropriate comment from the clinical coordinators (Al Sowygh [5]). Perceived stress is the perceptions or notions that a person has about the amount of stress they are under at a particular moment or over a period (Collins, et al. [6]). Depression, a negative outcome, is usually linked with increased stress levels. Depression and anxiety possess a satisfying association with the perceived stress scale (PSS), which implies its use in evaluating a person’s stress. This endorses the use of PSS in the stress evaluation throughout the COVID-19 surge (Raja, et al. [1]). An accurate estimation of an individual’s stress may be measured by utilizing various instruments that have been crafted to assist in the evaluation of a person’s stress levels. PSS is the first of these and a classic stress evaluation tool. The PSS is one of the extensively utilized tools used to assess stress perceptions, but in general, the psychometric properties of the PSS-10 are better than PSS-14. Hence, in research work and clinical practice, PSS-10 has been endorsed to be applied to analyze perceived stress. (Lee [7]) PSS is a self-report questionnaire fabricated to estimate “the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as stressful.” It estimates the extent to which a person has felt existence as overloading, uncontrollable and unpredictable over the last four weeks (Chan, et al. [8,9]). Based on their perception, the total score could allocate a person into low or high-stress categories. The validity, usefulness, and reliability of the PSS-10 scale have been observed previously (Lee [7,23]).

Coping is a unique acclimatization triggered in normal persons by unexpected stressful situations. To deal with orders that are especially demanding, possibly surpassing human abilities/assets, a human being undertakes constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts (García, et al. [11]). Coping can also be defined as cognitive and behavioral endeavors undertaken by individuals to either quell or value the needs fabricating the differences between the individual and the coexisting surroundings (Al Sowygh [5]). The coping process includes three main components: the source of the stress, cognitive appraisal, and coping mechanisms (García, et al. [11]). To compute the coping strategies, several scales have been designed. The most popular catalogue is COPE (Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced. It is a multidimensional checklist that has 15 scales, with each consisting of 4 items (Carver, et al. [12]). An abbreviated version was presented later called the Brief-COPE, extensively used in health sciences (Carver [13]). To cope with a taxing circumstance effectively and ineffectively, the Brief-COPE, a 28-item self-directed questionnaire, was designed. This tool has 14 subscales with two items each. Recently, Brief-COPE has been one of the best approved and most commonly applied tools of coping strategies. This scale is routinely applied in health services to check the patients’ emotional behavior in crucial situations. Brief - COPE is usually applied to evaluate the coping ability of an individual when put through an array of distress (García, et al. [11]).

The outbreak of COVID-19 infection has substantial consequences on the physical, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive conditions of dental professionals (Raja, et al. [1]). This pandemic has necessitated a lot of changes in the education system. Furthermore, dental graduates are at a higher risk for hospital-acquired infection and can turn into potential porters of the infection. So, the current situation is likely to have a greater psychological impact on the students, especially those in the clinical years of their course. Although there are several studies conducted on the stress levels of dental students in India (Jain, et al. [14,15]), very few surveys are conducted in Kerala (George [16- 17]) which has a large number of students graduating each year from the eighteen private and five government dental colleges. Moreover, the current public health emergency is unprecedented, so reports on perceived stress and coping strategies in this scenario have been very few. The present study intends to fill this lacuna. Analysis of data collected can help in planning interventional strategies to promote the psychological well-being of the students. Hence, the rationale of this survey was to analyze the level and kind of stress found among dental undergraduates of Kerala during the COVID-19 outbreak. This experience could be a model for designing a stress management plan for the future in the period of such a crisis. The aim was to assess the perceived stress levels and strategies for coping with stress among clinical dental undergraduates all along the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of the perceived stress scale-10 and Brief-COPE scale.

A self-directing, voluntarily engaging online questionnaire was employed in this cross-sectional study. The survey was customized for dental undergraduates. The candidates were enrolled by random sampling for this survey. The survey included all current third and final year students pursuing Bachelor of Dental Science (BDS) course in various Dental Colleges and Hospitals under Kerala University of Health Sciences. Institutions with unreachable administrations and undergraduates through various modes of communication were excluded. This study adheres to the STROBE protocol for cross-sectional studies. The pretested questionnaire was sent to all enrolled participants by using google forms via email or WhatsApp. Their email address or contacts were obtained from the students’ dental association. Before filling out the forms, the purpose of the study was explained, and anonymity was assured to the participants. Informed consent was collected from all enrolled undergraduates after obtaining approval from the Institutional ethical committee for conducting the survey.

Data was gathered online in an undisclosed manner from January2021 to June 2021, followed by three reminders. The questionnaire was made accessible for 6 weeks. To improve the response rate, prior information through a text message was sent via WhatsApp, and on completion of the official mail was also sent. Students were reassured about the confidentiality of the information provided by them, thereby addressing their fear of disclosure, punishment, and authorities forcing them to fill. Approximately five minutes were required to fill in the form by the enrolled students. As the software refused the submission of the incomplete forms, there was no data loss. Students’ participation was voluntary or anonymous and was disclosed on the first page of the survey form. A contact number of the department of psychiatry and counselling unit of Medical College was provided in case students felt stressed or disturbed while filling out the survey form. The sample size was estimated using power analysis, and the final sample size was set at 250. The study was conducted for six months to collect adequate representative samples. The questionnaire for this survey was drafted in English, and a link was provided to make the form available online. The questionnaire had three parts. The first part gathered information regarding demographics (gender, age, nationality, year of enrolment to college, year of study, living conditions, family status, and financial assistance). The second part evaluated their mental well-being using perceived stress levels (PSS- 10 scale), and the third part assessed the coping process using the Brief COPE Scale. The intention of the survey was initially expressed. On the top of the form, instructions to be read before answering the questionnaire were disclosed to all students.

PSS-10 is a ten-item questionnaire framed by (Cohen, et al. [9]) which is extensively applied to evaluate levels of stress in youngsters and young adults less than 12 years (Cohen, et al. [9]). It is composed of ten questions, requires 5-10 minutes to finish, and is for a person or group administration. The perceptions and thoughts in the past four weeks were enquired via the questionnaire. In every case, participants are enquired about how frequently they felt a certain way on a 5-point scale from never to very often. Responses are scored as: never = 0; almost never = 1; sometimes = 2; fairly often = 3; very often = 4. To calculate a total PSS score, answers to the four positively stated items (items 4, 5, 7 and 8) first need to be reversed (i.e., 0 => 4; 1 => 3; 2 => 2; 3 => 1; 4 => 0). The PSS score is then collected by adding scores of all items. Participants’ scores on the PSS can range from 0-40, with higher scores indicating higher perceived stress. Scores were categorized as 0-13, low stress; 14-26, moderate stress and 27-40, high perceived stress. Brief-COPE addresses the modes used by the participants to cope with the stress in life, including its’ intent and frequency of use. It is a 28-item multidimensional evaluation of strategies utilized for coping or modulating perceptions in reaction to stressors. This shortened checklist has items that assesses the number of times that a person employs various coping strategies computed on a scale from 1 (I haven’t been doing this at all) to 4 (I’ve been doing this a lot). There are 14 two-item subscales within it, and each is analyzed separately: active coping, acceptance, behavioral disengagement, denial, humour, planning, positive reframing, religion, self-distraction, selfblame, substance use, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support and venting. The scale estimates an individual’s primary coping styles with scores on the following three subscales: Avoidant Coping; Emotion-Focussed Coping and Problem-Focussed Coping. Data collected was managed by using Microsoft excel and SPSS software.

The data were analyzed using the SPSS version 20.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version (IBM Corp., Armonk NY, USA)) From the self-reported questionnaire responses, demographic data and descriptive statistics were tabulated. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Qualitative variables were expressed as frequency and percentage. Comparison of continuous variables between two groups was analyzed by student t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. Association between qualitative variables was analyzed by the Chi-square test. The relationship between quantitative variables was analyzed by Pearson correlation.

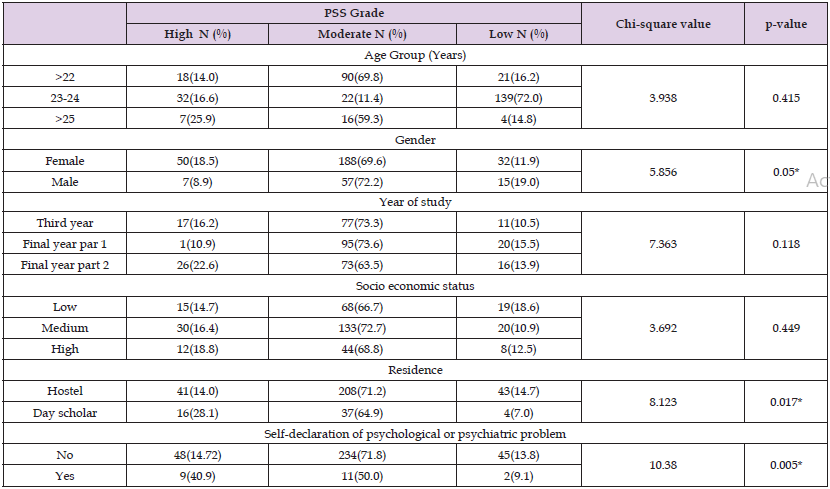

Among the 250 participants, 193 (55.7%) belonged to the 23–24- year age group, and 270 (77.4%) were females. The majority of participants, i.e., 129 (37.0%), belonged to the final year part 1, followed by BDS final year part-2 (33%) and third year (30.1%). Most students belonged to medium socio-economic status (52.4%) and resided in hostels (83.7%). Among study participants, 22(6.3%) reported having been diagnosed with psychological or psychiatric problems (Table 1). Among the age group, those above 25 years (25.9%) reported high PSS grades, while the 23-24 age group (72.0%) had low PSS grades. Female participants (18.5%) reported higher PSS grades compared to males (8.9%). In terms of years of study, final year part-2 participants (22.6%) had high PSS grades, followed by third-year participants (16.2%). The participants who reported suffering from any psychological or psychiatric problem (40.9%) had higher PSS grades (Table 2). Similar variations were evident when mean PSS scores were compared among the various factors (Table 3). Out of all factors, gender, residence, and self-declaration of prior mental health issues showed significant association with the PSS score (p < 0.05).

Table 2: Comparison of the socio-demographic variable-wise distribution of PSS grades among participants.

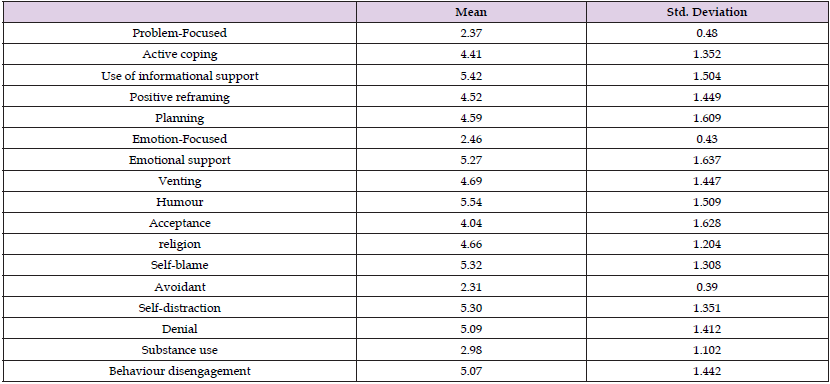

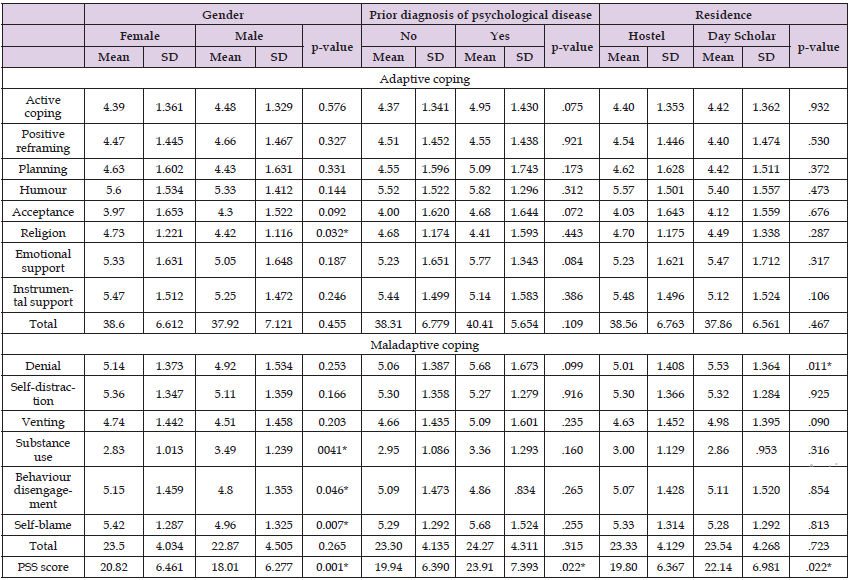

Assessment of overall mean scores of various sub-domains under the three coping mechanisms under COPE inventory among study participants revealed that under problem-focused coping, the maximum mean score was reported for the use of informational support (5.42±1.50) followed by positive refraining (4.52±1.45). For emotion focussed coping, the maximum mean score was reported for humour (5.54±1.51), and the least mean score was reported for acceptance (4.04±1.63). Lastly, under the avoidant domain of coping, self-distraction had the highest mean score of 5.30±1.35, and the lowest mean score was reported for substance use (2.98±1.10) (Table 4). The overall mean scores of Adaptive Coping and its dimensions were higher among females; significant difference based on gender was not observed. Similarly, the mean scores of overall maladaptive coping and its dimensions were also comparable based on gender, except for the dimension “substance use,” “behavior disengagement,” and “selfblame” (p <0.05). Likewise, females had a higher total PSS mean score (20.82 ± 6.45) compared to males (18.01 ± 6.28), and this difference was significant (p <0.01) (Table 5).

Table 4: Overall Mean scores of various sub-domains under the three coping mechanisms under COPE inventory among study participants.

Table 5: Comparison of Brief-COPE Scale scores and the PSS scores among the study population based on gender, prior history of the psychological issue, and residence status.

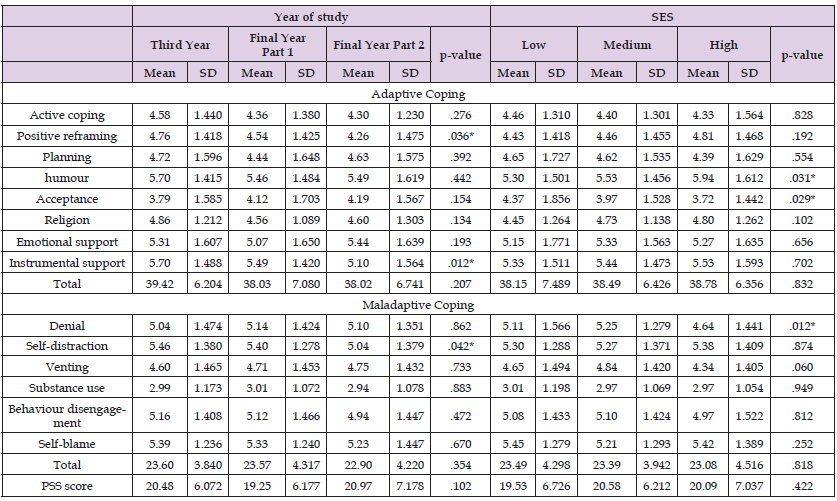

The overall mean scores of Adaptive Coping and maladaptive coping were higher among participants diagnosed with psychological or psychiatric disease in the past, but there was no significant difference for any of its domains as well as for total score. Likewise, participants who had been diagnosed with psychological or psychiatric disease in the past had a higher total PSS mean score (23.91 ± 7.39) compared to other participants (19.94 ± 6.93), and this difference was significant (p=0.02) (Table 5). The overall mean scores of Adaptive Coping and maladaptive coping were higher among day scholar participants, but no significant difference was observed for any of its domains and total score. Likewise, day scholar participants had a higher total PSS mean score (22.14 ± 6.98) compared to hostelite participants (19.80 ± 6.37), and this difference was significant (p=0.02) (Table 5). With respect to adaptive coping strategies, a statistically significant difference was observed based on the year of study for dimensions “positive reframing” (p = 0.036) and “instrumental support” (p = 0.012), with a higher overall mean score among third-year participants (39.42±6.20). The overall mean adaptive coping score was lower among fourth-year part-2 participants (38.02± 6.74), but a significant difference was not noted. Furthermore, the dimension “self- distraction” of maladaptive coping strategies showed a significantly high mean score (5.46 ± 1.38) among this year’s participants (p=0.04). Likewise, the total maladaptive mean scores were also higher among third-year participants (23.68±3.84), but a significant difference was not noted. On the other hand, based on the year of study, the overall mean PSS scores were significantly higher among final year part 2 participants (20.97 ± 7.18, but the difference was not statistically significant. (Table 5)In terms of adaptive coping strategies, a statistically significant difference was observed based on socio-economic status for dimensions “humour” (p = 0.031) and “acceptance” (p = 0.029). The overall mean adaptive coping score was lower among low SES participants (38.15± 7.50) without any significant difference. Furthermore, the dimension “denial” of maladaptive coping strategies showed a significantly high mean score (5.25 ± 1.30) among medium participants (p=0.012). The total maladaptive mean scores were also higher among low SES participants (23.49±4.30), but there was no significant difference. Based on SES, the overall mean PSS scores were higher among medium SES participants (223.39 ± 3.94), but a significant difference was not noted (Table 6). Pearson’s correlation analysis was done between coping strategies and PSS scores. A significant positive correlation with perceived stress score was recorded for adaptive coping strategies. But for maladaptive coping strategies, a non-significant significant negative correlation was found. There was a statistically significant positive correlation between emotional support (0.308), planning (.238), denial (.218), and acceptance (.135) with a PSS score. Whereas there was a statistically significant negative correlation between substance use (-.204), positive reframing (-.141), and use of informational support (-.105) with a PSS score (Table 7).

Table 6: Comparison of Brief-COPE Scale scores and the PSS scores among the study population based on year of study and socio-economic status.

The emotional, psychological, and social well-being of an individual is greatly influenced by the mental determinant of health (Endler, et al. [18-19]). The way students perceive and manage stress may have an impact on their academic performance, (Carver, et al. [12]) and stress in medical and dental education may unintentionally have a negative impact on student’s mental health (Gomathi, et al. [20]). The COVID-19 disease’s expansion has forced numerous adjustments in the educational system, which have affected how students perceive and handle stress and could impact their academic and professional success. The current study was conducted in order to determine the levels of perceived stress and coping techniques among clinical dental undergraduate students in Kerala during the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 crisis has significantly impacted the social, professional, and everyday lives of the general public—particularly those in the health professions, including dental students. The comparability of the results regarding the questionnaires used to assess mental health and/or perceived stress, as well as the particular social and geographic contexts where the studies were conducted, are key factors to consider when interpreting the findings. In order to comprehend the psychological burden that COVID-19 has placed on many communities around the world, many psychometric instruments have been designed to evaluate mental health in this time (León Manco, et al. [21]).

With around 77.4% of the participants being female, this study also found that there has been a rise in the number of women pursuing dental careers globally (Pallavi [22]). Similar to the findings of Crego, et al. [23] more women (68.7%) were enrolling as undergraduate dental students. But, Al-Sowygh et al. noted a male majority (68.9%) in the middle eastern region, which could be related to the country’s different cultural standards (Al Sowygh [5]).

Age was one of the sociodemographic characteristics that significantly affected the increase in reported stress in the current study; the older the individual, the more perceived stress was reported. These results are in contrast to those found in a study conducted on dental health care workers in Russia (Sarapultseva, et al. [24]). Still, it was similar to those reported by earlier studies, including dentists from China, India, Israel, Italy, UK, and Germany (Mekhemar, et al. [25- 26]). The reason for such a trend in the case of older students could be a decline in active social life. Stress levels were higher among female students in the current study. This result is comparable to that of Al-Sowygh (Al-Sowygh [5]), who likewise reported higher mean PSS scores among Saudi female dental students. It might be brought on by work demands, family obligations, or a lack of faith in clinical judgment. However, Tangade et al. found that Indian male dental students experienced higher levels of stress as a result of their obligations and a longer tenure in the field (Tangade, et al. [27]).

Final-year participants had PSS scores greater than those of their third-year counterparts. Similarly, many studies (Cohen et al. [9,12,28,29] found that fourth-year students had high levels of stress. Lack of leisure time, test anxiety, starting the clinical portion of training, being unable to keep up with clinical work, and failing to meet clinical obligations on time may be the stressors for fourth-year students, according to a plausible explanation for the above observation. Participants in the current study who disclosed having any psychological or psychiatric issues had higher mean PSS scores. Similar tendencies were noted in an Italian study, which found that participants in psychiatric care had considerably higher mean ratings on the Perceived Stress Scale than non-psychiatric care participants. In individuals with major mental illness, the actually experienced stress related to the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown restrictions may be a powerful predictor and mediator of the increased likelihood of experiencing severe anxiety. Due to their mental illnesses, they may have more COVID-19-related perceived stress than the normal population (Iasevoli, et al. [30]).

In the present study, day scholar students reported higher mean PSS scores in comparison to hostelite students. According to the study by Ravichandran et al., the day scholar participants had a higher overall PSS mean score than hostelite individuals (Ravichandran [31]). When students enter a hostel, they leave behind the security that comes from their families and homes. In a place where everything is unfamiliar—from the environment to the people to the rooms—their homesickness—also known as separation stress in college students— which makes it challenging for them to share with others—is exacerbated by the stress of a new setting and their academic performance. Positively, living in a hostel encourages a student to be outgoing and social. It enables pupils to communicate with their peers and teachers, form friendships, and grow into decent people who can make their own decisions. On the other hand, since the majority of dental colleges are normally far away from the cities, day scholar students are fatigued from their long commutes and lack of study time. Since they only communicate during class hours, day scholars don’t have as much peer interaction (Ravichandran [31]). Students also used a variety of coping mechanisms to deal with this intense stress. A significant positive connection between adaptive coping mechanisms and perceived stress level was observed. However, a non-significant significant negative association was seen for maladaptive coping mechanisms. According to the findings of another study, coping mechanisms did not significantly correlate with the overall stressor score. Coping tactics had a weakly positive correlation with stressor score (Bamuhair, et al. [32]). In contrast to the findings of the study by Veeraboina, et al. [33] females in the current study had higher mean scores for the “Denial” coping technique Veeraboina, et al. [33]. This could be because females have a harder time managing their time, workloads, and excessive expectations (Silverstein [34]).It was shown that students in their final year preferred stress-reduction techniques such as accepting and forming a plan to deal with challenges, communicating with others, and making people laugh much more than students in their other years. On the other hand, difficulties for fourth-year students can include a shortage of free time, exam anxiety, starting the clinical portion of training, being unable to keep up with clinical work, and failing to meet clinical requirements on time. This fourth-year group chose more unhealthy coping mechanisms, such as avoiding or quitting attempts and/or engaging in harmful activities, including smoking, drinking, and abusing drugs.

Although this is one of its kind studies done in the state of Kerala, one limitation of this study is that it was conducted in a single university study sample and used self-report measurement. Nonetheless, this study found a favorable association between “Self-blame” and “Venting,” which validated that the cycle of self-blame-stress-anxiety can be fuelled by feelings of helplessness and hopelessness resulting from the self-blame. People frequently feel inadequate and guilty and blame themselves for their mistakes while they are under stress. According to the current study, a student can handle stress better with a positive outlook. Positive reframing activity exhibited a substantial negative link with stress scores.

The current study showed that females, day scholar students, and final year part-2 dental students all reported significantly higher levels of perceived stress. Although the actual statistics may be greater than those presented here, very few students have admitted that they were dealing with psychological problems. The majority of students have been using adaptive coping techniques to combat stress. Students with high-stress levels also risk developing major mental illnesses if the problem is not addressed. As a result, early detection and management are necessary for reducing stress. Therefore, it is important to inform students about stress’s psychological symptoms and indicators. Moreover, stress avoidance and management measures should be incorporated into the dental curriculum to promote students’ well-being.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

None.