Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Imen Chebbi1*, Sarra Abidi2,3 and Leila Ben Ayed3

Received: June 24, 2024; Published: July 10, 2024

*Corresponding author: Imen Chebbi, FSEG Sfax, University Sfax, Tunisia

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.57.009010

To better avoid injuries in sports, prevention strategies increasingly include modern techniques like machine learning that allow for an evaluation of injury risk. This article aims to assess the injury risk for 250 athletes. The risk indicators measured daily were the athletes’ views of their physical and psychological conditions, which they self-reported each morning and evening using a customized application. The output data matched the injuries reported by the athletes. A Decision Tree model was trained and optimized to predict the incidence of an injury using the measured variables. Our model’s performance score accuracy = 99.60. Estimating the risk of injury is challenging due to the disparity between the number of injuries and observations. The pre- diction model identified physical and positive emotional elements as the most influential.

Keywords: Machine Learning; Decision Tree Model; Injury; Prediction

The application of machine learning approaches to estimate injury risk has grown in popularity across a variety of areas (Dandrieux, et al. [1]), suggested a machine learning-based daily injury risk estimation feedback (I-REF) system for track and field athletes, with the goal of analyzing the association between I-REF use and injury burden (Sun, et al. [2]), investigated adaptive restraint design utilizing machine learning to improve safety for varied populations, revealing the significant injury risks associated with specific demographics (Shi, et al. [3]), created an artificial intelligence system for predicting acute kidney injury in ICU patients with gastrointestinal bleeding, demonstrating the utility of machine learning in healthcare settings. Similarly (Tu, et al. [4]), used machine learning algorithms to predict mortality risk in ICU patients with traumatic brain injury, proving the utility of such models in critical care settings (Horwitz, et al. [5]), investigated the application of a machine learning model to predict clinical outcomes of sulfur mustard-induced ocular injury, highlighting the predictive possibilities of machine learning in injury assessment. Furthermore (Shahidi, et al. [6]), studied machine learning risk estimation for mortality prediction in continuing care institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic, demonstrating machine learning’s potential to improve risk prediction beyond traditional parameters. Furthermore (Fachet, et al. [7]), used predictive machine-learning modeling to assess the probability of detrimental consequences in polytrauma patients, demonstrating the power of machine learning in detecting predictive markers for injury patterns (Lin, et al. [8]). created prediction models for acute kidney injury in critically ill patients with acute pancreatitis, highlighting machine learning’s use in health- care settings. Overall, the papers examined reveal machine learning’s wide uses in evaluating injury risk across multiple domains, demonstrating its promise for improving safety measures and predicting unfavorable outcomes in distinct populations. This article will examine the injury risk for 250 athletes.

Daily risk indicators included the athletes’ perceptions of their physical and psychological conditions, which they self-reported each morning and evening using a tailored application. The results matched the injuries reported by the athletes. A Decision Tree model was trained and optimized to predict the occurrence of an in- jury based on the measured data. Figure 1 shows the core idea of the proposed framework. The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

• Section 2 describes the Literature review.

• Section 3 Fundamentals.

• Section 4 presents our approach.

• Section 5 presents Material and method.

• Section 6 Evaluation and Discussion.

• Section 7 outlines conclusions and future lines of work.

Due to its relative simplicity in comparison to other options, decision tree models have been utilized extensively for classification problems in a variety of fields (Daghero, et al. [9]). Various medical disorders have been predicted and detected in the healthcare environment through the use of machine learning techniques, such as decision tree models. When it came to forecasting acute kidney injury in trauma patients (Choi, et al. [10]), compared machine learning approaches with logistic regression and found that the machine learning model performed better. Similar to this (Li, et al. [11]), found variation in the trajectories of teenagers’ non-suicidal self-injury behavior based on factors related to their families through the use of a decision tree analysis (Shearah, et al. [12]). demonstrated the potential of decision- making systems in healthcare by proposing an intelligent framework for the early detection of severe pediatric disorders from modest symptoms. Additionally, based on sensor behavior data (Magana, et al. [13]), used machine learning algorithms to detect and forecast digital dermatitis in dairy cows early on, illustrating the usefulness of behavioral patterns in health monitoring systems. Decision tree models are used in a variety of fields outside of healthcare, as demonstrated by the study by (Xue, et al. [14]), which built a Kinect-based variable spraying control system for orchards. Furthermore (Vlasakova, et al. [15]), assessed the efficacy of biomarkers in identifying damage to the nervous system, highlighting the significance of precise detection techniques in diagnosing neurological disorders. The examined literature underscores the importance of decision tree models in the detection and prediction of injuries in diverse sectors, hence demonstrating their potential to improve diagnostic accuracy and healthcare outcomes (Figure 1).

Two of the most essential components of the study reported in this paper are the ideas of damage detection and the machine learning (ML) techniques used to evaluate the dataset; these subjects are extensively discussed in this section.

There are numerous typical kinds of injuries, such as:

Bruises: These are wounds from direct strikes or impacts to the body’s delicate tissues. Mild to moderate bruises can heal on their own, but more serious ones might need to be seen by a doctor.

Sprains: Ligaments are bands of tissue that attach bones to one another. These injuries are to the ligaments. Sprains vary in severity and can be brought on by trauma, abrupt movements, or overuse.

Fractures: These are fractures in the bones brought on by trauma, overuse, or underlying illnesses like osteoporosis. Every bone in the body can sustain a fracture, which can be minor or severe.

Contusions: These bruises were brought on by a direct hit to the body. Any area of the body might sustain a contusion, which can be minor or severe.

Cuts and lacerations: These are wounds when there is a break in the skin brought on by trauma or sharp objects. They might need to be treated medically and might be minor to severe.

Burns: These are wounds brought on by being near heat, chemicals, or electrical current. The body may have long-term repercussions from minor to severe burns.

Concussions: These are certain kinds of traumatic brain injuries brought on by head trauma. Concussions can alter behavior and cognition and have long-term repercussions on the brain.

Dislocations: These wounds happen when a bone is pushed out of the joint’s natural alignment. Dislocations range in severity from moderate to severe and can be brought on by trauma or misuse. Protective clothing should be worn, sharp things should be handled carefully, exposure to chemicals and electricity should be avoided, and stretching should be done frequently to prevent accidents. Furthermore, fractures can be avoided by upholding strong bones by a balanced diet and consistent activity. It is possible to reduce the risk of concussions by wearing protective headgear when playing sports or engaging in other activities that could hit the head. In the event of an injury, it’s critical to get medical assistance when required, particularly in cases of serious or potentially fatal injuries. Figure shows types of injuries (Figure 2).

A decision tree model is a machine learning technique that is tree-structured and hierarchical, and it is utilized for both regression and classification tasks. There are four main nodes in it: the root, branches, internal, and leaf nodes. The internal nodes, often referred to as decision nodes, receive the outgoing branches from the root node, which does not have any incoming branches. Both types of nodes perform assessments based on available attributes to create homogeneous subsets, which are represented by leaf nodes or terminal nodes. Every conceivable result in the dataset is represented by the leaf nodes. Using a divide and conquer approach, decision tree learning finds the best split using a greedy search that is then performed top-down and recursively until all or most of the records are classified under particular class labels. To sum up, decision tree models are a class of supervised learning algorithms that are applied to tasks involving regression and classification. They produce homogeneous subsets of data through a divide and conquer tactic and have a hierarchical, tree-like structure. Using a greedy search to find the best split, decision tree learning uses pruning to cut down on complexity and avoid overfitting. Using ensemble techniques like random forests can increase accuracy (Figure 3).

The Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) generates synthetic minority class examples in order to rectify class imbalance in datasets. In SMOTE, the minority class is oversampled by creating artificial examples that resemble real minority instances. Using line segments that connect randomly picked data points and their closest neighbors in the minority class, this strategy creates new data points along the feature space gap in an attempt to fill it. In order for SMOTE to function, each observation in the minority class must be iteratively chosen. Next, each observation’s k nearest neighbors must be determined, and synthetic observations must be created between the chosen data point and its neighbors. In order to establish the direction and distance for creating synthetic instances, the algorithm chooses neighbors at random. A percentage is given to indicate how much oversampling is necessary; larger percentages result in the creation of more synthetic instances. Figure 4 shows the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) (Figure 4).

A machine learning method called Randomized Search CV is used to tune hyperparameters by examining random combinations of hyperparameters inside predefined distributions. It is especially helpful in cases where the hyperparameter search space is huge, and it might not be practical for more complex models or extensive searches for hyperparameters. Randomized Search CV works by randomly selecting a set number of hyperparameter combinations from the defined distributions. This enables efficient exploration of a wide range of hyperparameter combinations, as compared to Grid Search CV, which searches the entire search space by attempting every possible hyperparameter combination. Figure 5 shows The Randomized Search CV.

In this study, we used Decision Tree model where each class corresponds to a state injury to the athlete. The low ratio between the number of injuries and the number of observations available in the database, 182 sure injuries for 3722 observations, or 5.1% of the total number of observations, accounts for an im- balance between the two classes to predict. The fourth stage walks through the rehabilitation procedure. Additional details are in the following subsections.

The process of collecting information. This phase’s main objective is to prepare and collect data. In our case, data was obtained by means of an examination conducted by the Ministry of Sports Tunisia. A file named sport.csv holds all of the information we collected (Figure 5).

To prevent problems in estimating the risk linked to this characteristic of the dataset, we applied an oversampling technique to training data titled SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique).

The model parameters were determined using a randomized grid- Search. The Randomized Search CV is a technique for optimizing the hyperparameters of machine learning models. It is used to find the hyperparameters that maximize model performance on our dataset, by carrying out a search randomization of the model hyperparameters. It consists of defining a range of values for each hyperparameter, then to choose a set of random values for each hyper- parameter and to evaluate the model for each combination of hyperparameters. We have used a decision tree model in this work.

The process of rehabilitation. If there are any injuries at this point, the physician suggests a rehabilitation plan. Days without physical exercise were used to determine the severity of the injury. We’ve determined four severity levels:

• Level 1: No suspension of activity.

• Level 2: suspension of less than 8 days;

• Level 3: 8 to 30 days of unavailability.

• Level 4: 30 days or more of interruption or requiring hospitalization, cast or surgical care.

This evaluation is done using the stratified cross validation technique which consists of dividing the data into several subsets, called “folds”, and to evaluate the model on each of these subsets. Our research was carried out on a stratified cross-validation in 5 levels. The model parameters to be optimized are the depth maximum of the tree, the maximum number of parameters and the classification criterion. The data was separated into training set and test set according to the ratio 75–25%. Thus, the model was trained on the training set then evaluated on the test set. Our approach is shown in the Figure 6.

In a cross-sectional study founded on exploratory research, athletes approved by the Ministry of Sports Tunisia were questioned about their expectations, communication preferences, and views on the importance of injury prevention.

Ministry of Sports Tunisia, is where we worked on our questionnaire. Between May 2023 and January 2024, 250 practitioners who had been approved by the Ministry of Sports Tunisia were interviewed. Prior to conducting in-person interviews, paper tests that Ministry of Sports Tunisia members could read were distributed. Telephone contact was made for incomplete forms and missing subjects. All the data was gathered by one individual. Figure 7 depicts the scenario of the investigation. Athletes may choose to seek medical advice or not, but an injury is defined as “pain, discomfort, or an injury to the musculoskeletal system, occurring during the practice of sport (training or competition) and having had a negative impact on sports practice (reduction in practice, adaptation and in- complete practice, or cessation of practice)” (Figure 7). Every day, prospective injury data was gathered on a form that each athlete had to fill out in the evening. The possibility of an injury could be self-reported by the athlete in accordance with four severity levels:

• No, no injury or physical problem.

• Yes, injury but full participation in training and competition.

• Yes, injury but reduced participation in training and competition.

• Yes, injury but no possibility of training or competition participation.M

The study population included 250 athletes (150 women, 100 men). The average age of the study population ranged from 18 to 22 years and older. Table 1 contains detailed data and information on the age of the participants. The response rate to the quiz is 90.30%. Table 2 presents an explanation of the many physiological and psychological factors, the assessment period, and the measuring scale (Tables 1 & 2). Days without physical exercise were used to determine the severity of the injury. We’ve determined four severity levels:

• Level 1: No interruption of operations.

• Level 2: suspension for fewer than eight days

• Level 3: unavailable for eight to thirty days

• Level 4: a disruption lasting 30 days or longer, or the need for hospitalization, casts, or surgical care.

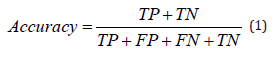

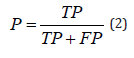

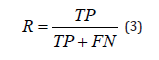

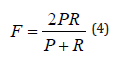

The suggested approach is compared and assessed using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve. In this study, we used macro and micro averages of recall, precision, and F1-Score. Multiple-class classification score. The confusion matrix (CM) can be used to create all the metrics stated above. Table 1 shows that while CM is built for binary classes, it can be extended to many more (Table 3). Table 3 shows the amount of classpos data that is predicted to actually be- long in classpos, the amount of classneg data that is predicted to actually belong in classneg, the amount of false positive (FP) data that is predicted to be class- neg but actually belongs in classpos, and the amount of false negative (TN) data that is predicted to be classneg but actually belongs in classpos. The evaluation metrics are computed using the terms mentioned above.

It is the percentage of cases that are accurately categorized as all instances. Also referred to as detection accuracy, it is a useful performance metric that is only present in datasets that are balanced.

It is the ratio of correctly predicted Attacks to all samples that were predicted as Attacks.

It shows the ratio of samples correctly recognized as assaults to samples that are attacks in fact. Another name for it is “Detection Rate.”

The Precision and Recall harmonic mean are how it is defined. Put another way, it’s a statistical technique that evaluates a system’s accuracy by considering its recall and precision.

We created a database using the results of the test administered by the Ministry of Sports Tunisia in order to evaluate the efficacy of our recommended approach. We generated a CSV file called “sport. csv” that includes all of the athletes’ personal data, including name, age, birthdate, and total number of injuries. This file served as a model’s input. In our case, we chose to work with Google Colab, a product of Google Research. Because Colab allows anyone to write and run any Python code via a browser, it complies with data privacy laws. It’s an ideal environment for instruction, machine learning, and learning from data. In technical terms, Colab is a hosted Jupyter notebook service that provides free, configuration-free access to computer resources, including GPUs. We have tested our model numerous times. Table 4 shows the best experimental results for us to quantify fatigue and recovery, better understand adaptability to training (Table 4). Programs, and reduce the risk of illness and injury, an effort should be made to better understand the relationship between training and competition load and injuries. In sport, a few data points have been combined for analysis and harm forecasting.

However, it wasn’t until recently that the available data set was examined using the appropriate statistical techniques. Thanks to machine learning’s advances in autonomous and interactive data analysis, the nuances of the relationship between player load and injury are now more known. Here, we contrast our method with that of a few other machine learning-focused works: (Vallance, et al. [16-24]). Table 5 presents a comparison between our best research on sports injuries and the research of other authors (Table 5). A comparison of the suggested Behavior sport-AI model’s accuracy with other benchmark models is shown in Figure 8, which indicates that Behavior Sport-AI is more accurate than the other models. In terms of accuracy, the proposed Behavior sport-AI model outperforms its comparable peers, with 99.60%. Table 5 presents an accurate comparison between the proposed model and existing literature models. In other cases, the results are summarized without providing details about the injuries discovered, and some of the models being compared don’t use cross-validation. Though more research is required to compare our findings with those of the literature, the overall result shows the value of utilizing Behavior sport-AI to detect injuries in the data set. By employing these methods, one can somewhat reduce the performance achieved while maintaining the outcomes with those of other similar studies.

Predictive models, like the Decision Tree model, reduce interactions between variables and challenge current inaccurate predictions that result from overly complicated models (Figure 8). These kinds of algorithms can be used to identify harm in sports. This aids in determining the contributing causes to sports-related injuries in the broader community. Sport injuries can be decreased by raising awareness, enacting laws requiring protective gear use in high-risk activities, and motivating athletes to use it on a regular basis. It is important to inform athletes about the risks of sports injuries and how they can affect them. The purpose of this essay is to evaluate 250 athletes’ risk of injury. The athletes’ assessments of their physical and mental health, which they self-reported every morning and evening using a personalized application, served as the risk indicators that were monitored daily. The athletes’ reported injuries corresponded with the output data. Using the measured characteristics, a Decision Tree model was trained and optimized to predict the likelihood of an injury. The accuracy performance score of our model is 99.70. Because of the discrepancy between the number of injuries and observations, estimating the risk of injury is difficult. Physical and positive emotional aspects were found to be the most influential by the prediction model. More effective strategies to improve our approach’s detection rate and accuracy will be explored in future study.