Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Jared Engelman1 and Stephen M Riordan1,2*

Received: July 01, 2024; Published: July 08, 2024

*Corresponding author: Stephen Riordan, Senior Staff Specialist and Head, Gastrointestinal and Liver Unit, Prince of Wales Hospital, Barker Street, Randwick NSW 2031, Australia

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.57.009002

Iron therapy-refractory iron deficiency anaemia has previously been reported with benign hepatic adenomas, Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma is a rare malignant tumour of the liver. Here we report for the first time a case of profound iron deficiency anaemia, despite plentiful hepatic and bone marrow iron stores and refractory to parenteral iron supplementation, in a patient with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, fully reversed by resection of the liver tumour.

Iron therapy-refractory iron deficiency anaemia has previously been reported with benign hepatic adenomas, either postulated or shown to be related to increased synthesis by the adenomas of hepcidin (hepatic bactericidal protein), a key regulator of iron homeostasis [1-3]. Hepcidin inhibits the transport of dietary iron from the duodenum to the plasma, the release of recycled iron from macrophages and the release of stored iron from hepatocytes, resulting in iron-deficient erythropoiesis [4]. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma is a rare malignant tumour of the liver. Here we report for the first time a case of profound iron deficiency anaemia, despite plentiful hepatic and bone marrow iron stores and refractory to parenteral iron supplementation, in a patient with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, fully reversed by resection of the liver tumour.

A 36-year-old Caucasian male presented with progressive lethargy over the previous 12 months. He reported vague epigastric discomfort over the past few weeks, described as constant in nature and unrelated to eating or posture. There was no weight loss and no history of overt gastrointestinal bleeding. He was a teetotaller and took no regular medications. He was previously well, with no family history of anaemia or liver disease. On examination, he was afebrile. Conjunctival pallor was evident. He was normotensive with a heart rate of 74 bpm and regular in timing in amplitude. Firm hepatomegaly was evident with a liver span of 18 cm. There were no peripheral stigmata of chronic liver disease. There were no features of portal hypertension or hepatic functional decompensation. Spleen was impalpable.

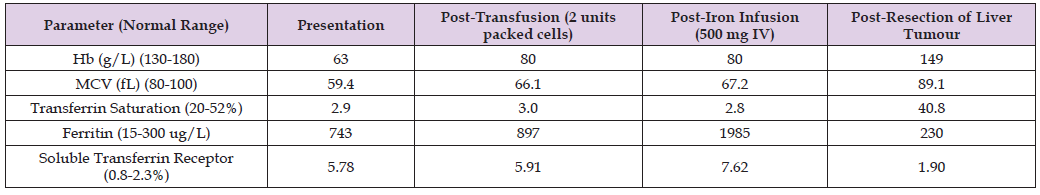

There was no lymphadenopathy. Results of investigations included a haemoglobin level of 63 g/L (normal 110 g/L to 180 g/L) with a normal white cell count and platelet count. Marked reductions in mean corpuscular volume (MCV) (59.4 FL; normal 80-100 FL) and in mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) (16.1 pg; normal 26-33 PG) were evident. The blood film demonstrated hypochromasia and microcytosis. The reduced MCV and MCH levels and blood film findings were in keeping with iron deficiency as the cause of the anaemia. Notably, the haemoglobin and red cell indices had been normal two years earlier, excluding thalassaemia as an alternative explanation. Results of iron studies are shown in Table 1, notably including a marked increase, rather than the expected reduction, in serum ferritin level.

The reticulocyte count was normal. Vitamin B12 and folate levels were normal. A haemolytic screen was negative. Results of liver biochemistry and international normalised ratio (INR) are shown in Table 2, highlighting a cholestatic hepatitic abnormality with normal markers of hepatic function, including the serum albumin level, a pointer that the elevated serum ferritin level was not the consequence of an acute phase response. The C reactive protein level was normal. Testing for a range of viral, metabolic and immune-mediated causes of liver enzyme disturbance (including serology for hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections, alpha-1-antitrypsin, caeruloplasmin, smooth muscle antibody, liver kidney microsomal antibody, anti- mitochondrial antibody and serum immunoglobulins) proved to be negative. Dynamic phase computerised tomography (CT) of the liver demonstrated a very large, arterially-enhancing tumour.

There was no evidence of intra-lesional haemorrhage, intra-abdominal or retro-peritoneal haemorrhage (Figure 1). Peripheral blood concentrations of the tumour markers, alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9, proved to be normal. A 99m-technetium sulphur colloid scan demonstrated no uptake, a pointer against focal nodular hyperplasia as the aetiology of the liver lesion. There was no evidence of extrahepatic involvement on staging CT of the abdomen and chest or on staging bone scan. Approach to initial management and further investigation included correcting symptomatic anaemia, determining the cause of the presumed iron deficiency, clarifying the nature of the liver lesion and managing this as appropriate. He was transfused 2 units of packed red cells and the haemoglobin level increased from 63 g/L to 80 g/L. Gastroscopy, colonoscopy and capsule endoscopy of the small intestine demonstrated no cause for gastrointestinal blood or iron loss.

The clinical course was marked by ongoing epigastric discomfort. The size of the liver tumour was beyond Milan criteria [5] for liver transplantation and he was worked up for the possibility of resection. Given that an extended right hepatectomy would be required, staged procedures were carried out in order to assess likely hepatic functional reserve in more detail and in order to optimise this following partial hepatectomy. Baseline assessment of indocyanine green clearance, a useful index of overall hepatic function, was found to be normal. Biopsy of the non-tumorous left lobe of the liver demonstrated only very mild, simple macrovesicular steatosis, without hepatic fibrosis. Notably, plentiful hepatic iron was apparent on Perls’ Prussian blue staining of the non-tumorous liver (Figure 2). A bone marrow biopsy also demonstrated plentiful iron stores (Figure 3). He received an intravenous iron infusion in the form of ferric carboxymaltose (500 mg) following the liver and bone marrow biopsies.

The iron deficiency anaemia proved to be refractory to parenteral iron supplementation, with no increase in haemoglobin or MCV values, which remained markedly reduced. The serum ferritin level and the soluble transferrin receptor concentration both increased further following the iron infusion (Table 3). Percutaneous embolisation of the right portal vein was performed in order to induce hypertrophy of the planned remnant left lobe to reduce the possibility of post-operative hepatic functional decompensation. Progress CT imaging 6 weeks later showed that the left hepatic lobe volume had increased by around 10% compared to the pre-right portal vein embolization level. The patient then proceeded to an extended right hepatectomy to resect the large liver tumour (Figure 4), which was found to be a fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (Figures 5 & 6). The patient made an uneventful post-operative recovery. Iron deficiency anaemia and markers of iron homeostasis rapidly normalised following tumour resection, as shown in Table 3. Liver enzyme values also normalised. The patient has remained well, with no evidence of tumour recurrence, anaemia or disturbed iron metabolism during an eight year period of on-going follow-up.

Table 3: Summary of haemoglobin (Hb), mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and iron studies post-blood transfusion, post-iron infusion and post-resection of liver tumour, compared to values at presentation.

Iron deficiency anaemia, refractory to iron therapy, has previously been reported in association with benign hepatic adenomas [1-3]. Here, we report for the first time that this phenomenon may also occur with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, a malignant liver tumour. That the iron therapy-refractory iron deficiency anaemia was the consequence of the fibrolamellar carcinoma was established by the fact it was rapidly and fully reversed following surgical removal of the liver tumour and has not recurred over an eight-year period of follow-up. Over-expression of hepcidin has been found to account for instances of iron therapy-refractory iron deficiency anaemia related to benign hepatic adenomas [2,3]. Hepcidin plays a central role in iron homeostasis via its interaction with the iron transporter, ferroportin. Synthesis occurs predominantly in the liver and is regulated by iron stores, erythropoietic activity, hypoxia, inflammation and Toll-like receptor 4 [4,6-8].

Increased synthesis of hepcidin inhibits the transport of dietary iron from the duodenum to the plasma, the release of re-cycled iron from macrophages and the release of stored iron from hepatocytes, resulting in iron-deficient erythropoiesis [4]. We postulate that over-expression of hepcidin by the tumour also occurred in our patient with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, in whom iron therapy-refractory iron-deficient erythropoiesis, fully reversible after subsequent surgical resection of the tumour, occurred despite documentation of plentiful iron stores in both the liver and bone marrow, in keeping with the known effects of hepcidin excess. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma is a rare variant of hepatocellular carcinoma [9], comprising less than 1% of all hepatocellular carcinoma cases in the United States [10]. It differs from more prevalent non-fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma in that it more often arises in younger patients with no underlying chronic liver disease and with an equivalent prevalence in females and males. It is named after the thick fibrous bands that surround the tumour.

Pathogenesis remains poorly understood, although molecular studies have found a unique DNAJB1–PRKACA fusion transcript, absent in non-fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinomas, in up to 70% of cases [11]. Aberrant production of hepcidin, as we postulate in our patient with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, has not previously been reported in any form of hepatocellular carcinoma. We conclude that malignant fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma is a cause of iron therapy-refractory iron-deficient erythropoiesis, fully reversible after its surgical resection, a phenomenon previously reported only with benign liver tumours. We postulate, based on our demonstration of plentiful iron stores, that over-expression of hepcidin by the fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, as previously demonstrated with benign hepatic adenomas, is the responsible mechanism.