Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Kashfi Pandi1, Tazul Islam1, Iffat Tasnim Haque1 and Hamida Khanum1,2*

Received: June 17, 2024; Published: June 26, 2024

*Corresponding author: Hamida Khanum, Department of Zoology, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.57.008971

A prudent allocation of resources towards public health yields significant economic benefits, such as enhanced quality of life, increased life expectancy, and improved physical and mental well-being for the entire nation. Presently, South Asian countries are experiencing a shift in disease patterns, necessitating a postpandemic overhaul of their healthcare systems. This review examines the economic ramifications of investing in public health from the perspective of South Asian nations. Existing global evidence demonstrates a positive correlation between health expenditure and economic growth in numerous studies. However, certain communities have observed contrasting or diminished economic outcomes despite health expenditure. These inconsistencies can be attributed to factors such as inadequate adherence to investment policies, political and systemic corruption, inequitable resource distribution, and insufficiently skilled workforce. Addressing the significant gaps in public health services in South Asian countries must be prioritized to ensure a healthy population. Investing in public health can lead to improved management of public health issues, potentially fostering a competent human capital and stimulating economic growth. Nonetheless, any factors that impede economic growth in relation to public health investment must be earnestly addressed at the national level.

Keywords: Health Expenditure; Public Health Investment; Economic Growth; South Asian Countries

The interconnection between population health and economic growth prosperity is a compelling field of research, one that holds profound implications for policy-making and national development strategies. This symbiotic relationship posits that a healthy population, nurtured by robust and effective public health infrastructure, can significantly contribute to a nation’s economic development [1]. However, the precise economic ramifications of such investments remain the subject of scholarly debate [2]. Investment in a nation’s populace is of paramount importance, as the workforce’s capabilities and efficiencies are contingent upon several variables, including the quality of life, societal conditions, and the prevailing health status. Enhancing a population’s health, through direct and targeted initiatives, may yield multifaceted benefits-including increased productivity, enhanced education levels, and enriched skill sets. These advantages, in turn, could catalyze greater economic prosperity, increased earnings, and a more robust investment and capital resource environment [3].

Various economic theories and empirical studies have illuminated the link between human capital development, particularly health, and economic performance. The endogenous growth theory, propounded by economists such as Romer, Lucas, and Rebelo, posits that the velocity of convergence is dependent upon the accrual of human resources, material, and technological innovation [4,5]. This theory underscores the critical role of health as a factor that directly impacts manpower and, consequently, economic growth [6-11]. Public health, a field dedicated to improving society’s collective health status, can be instrumental in transforming human capital into a more efficient and productive workforce. Numerous previous studies provide evidence of a significant causal relationship between investment in healthcare and resultant economic growth [12-16]. However, these studies pre dominantly focus on developed countries, leaving a critical gap in understanding the dynamics of this relationship in developing regions, especially South Asia. In the South Asian context, the full potential of health investment is often impeded by inadequate health system infrastructure, inefficiencies in service delivery, and a lack of health awareness. These challenges necessitate a comprehensive exploration and understanding of the relationship between health development, expenditure, and economic growth in resource-constrained settings. This review aims to examine the existing body of knowledge regarding the nexus between public health and economic expansion within the South Asian region.

It is guided by the underlying premise that optimizing public health practice is a national priority and a vital conduit towards strengthening the symbiotic relationship between human capital and national growth. As the primary source of literature, PubMed was used. The search terms used were ‘public health investment’. ‘Public health development’, ‘health expenditure’, ‘public health expenditure’, ‘public health budget’, ‘health’, ‘public health’, ‘economic growth’ ‘economic development’, ‘economic expansion’, ‘economy’, ‘south Asia’, ‘developing countries’. These words were used in different combinations to include the most likely published paper. Selected publications were limited to those from the last twenty years from the date of the review, although a few older publications were also used to provide some background information.

South Asian nations including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka are rigorously striving towards the accomplishment of universal health coverage, aligning their strategies with sustainable developmental goals [17]. However, they grapple with significant inequality in healthcare accessibility, particularly in rural and remote regions. Marginalized communities and low-income individuals often encounter considerable hurdles in availing essential health services. The shortage of skilled health workers amplifies these challenges further. The COVID-19 pandemic unveiled and aggravated the pre-existing health disparities and challenges in South Asia. It imposed a state of extreme emergency on global health care systems, with countries of limited resources, such as those in South Asia, revealing their vulnerability. The pandemic not only increased morbidity and mortality rates but also generated extended health impacts among recovered cases. The complexities and costs related to tracing, isolating, managing, and following up on COVID-19 cases, along with the protection and isolation of healthcare providers, disproportionately burdened the South Asian region [18,19]. Lockdowns and travel restrictions additionally disrupted essential healthcare services, thereby underlining the urgent need for robust public health investment and emergency preparedness. By the end of the Millennium Development Goals target period, substantial improvements were observed in infant and maternal mortality rates, and immunization status in Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka [20- 23]. However, populous countries like India and Pakistan struggled to achieve similar progress [24]. It’s noteworthy that a substantial portion of global maternal and child (under 5 years) deaths occur in this region [25-28]. South Asia also houses approximately 33.4% of the global extreme poor population, second only to sub-Saharan Africa, contributing to significant health system infrastructural gaps [29]. Despite considerable progress in health coverage in Afghanistan, the pace of growth has been stymied by the pandemic and political unrest [30]. Thus, for achieving sustainable universal health coverage, it is crucial to allocate capital resources to enhance health infrastructure and develop an efficient health service system [31]. The past three decades has seen significant public health improvements in Bangladesh, the Maldives, and Bhutan in alignment with the Millennium Development Goals [32-35].

However, these countries face persistent challenges ranging from communicable diseases, nutritional deficiencies, water and sanitation issues, to non-communicable diseases and health education gaps. India, in a state of continuous transition, has demonstrated remarkable health improvements over the past decades. Despite these advancements, the nation’s healthcare system faces enormous challenges with the equitable distribution of healthcare services among its diverse population [36]. Similarly, in Pakistan, despite some progress, the health system lags in terms of healthcare quality and access [37,38]. The Maldives and Nepal have made impressive strides in health systems over the past few decades, yet the universal expansion of both curative and preventive services is hampered due to structural insufficiency and competency gaps [33,39]. Sri Lanka has achieved significant progress in health sectors but has recently been thrown into crisis due to economic turmoil [40,41].

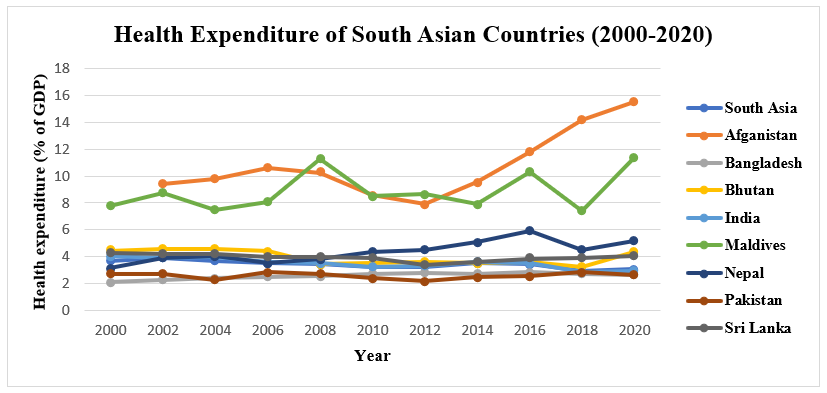

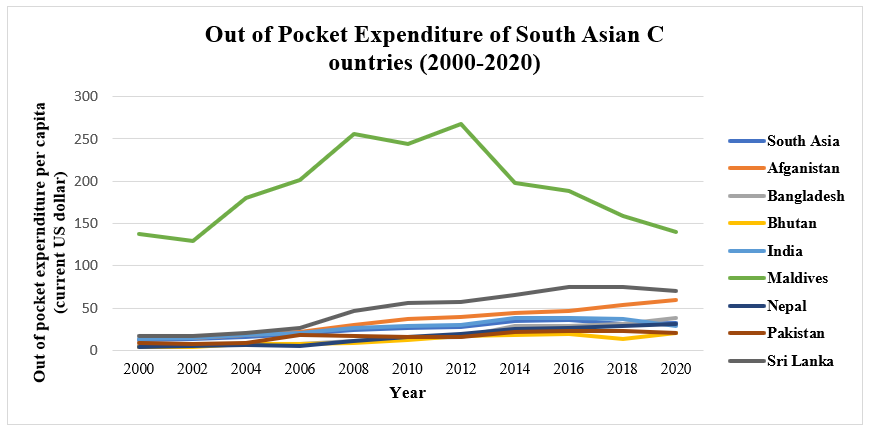

Healthcare services play a pivotal role in the development and wellbeing of societies, with investments in their accessibility and quality directly fueling economic growth. In this context, the South Asian region presents a complex scenario (Figure 1). The Figure 2 illuminates the disparity in health investment across the South Asian countries over the past two decades. Among the South Asian countries, Afghanistan and the Maldives were observed with greater and increasing expenditure of GDP for health. Other countries of this region were observed with a little change in health expenditure for last 20 years. Due to rapid urbanization, lifestyle habits have undergone significant changes over the last few decades, resulting in a tremendous increase in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and other conditions that pose significant risk factors for various NCDs, including obesity, sedentary lifestyles, the consumption of junk food, and excessive screen time. To cope with the growing population and increasing healthcare demand, it is essential to address the existing challenges. Strengthening healthcare delivery and ensuring universal and accessible healthcare for all will foster overall national growth. Additionally, it is crucial to address emerging health challenges. This includes addressing healthcare infrastructure gaps, strengthening healthcare delivery, tackling emerging health challenges, reducing out-of-pocket expenditure, promoting economic productivity, and achieving universal health coverage. Such investments are crucial for the well-being and future prosperity of the nations and their populations. One of another significant barriers to healthcare in South Asia is the high out-of-pocket expenses which include consultation fees, medication costs, and transportation expenses [42].

Figure 1: Comparative Analysis of Healthcare Expenditure in South Asian Countries as a Percentage of GDP (2000 - 2020).

Figure 2: Breakdown of Average Out-of-Pocket Expenditure in South Asian Countries (Current US dollars).

These costs pose considerable challenges for low-income individuals and households in availing essential health services [42]. The Figure 2 provided a detailed insight into the categories of outof- pocket healthcare expenses in South Asia, causing the most financial burden to the citizens. Total out of pocket expenditure is highest for India where the total out of pocket expenditure in private sector is highest in Bangladesh [42]. Like health expenditure, out of pocket expenditure pattern is also nearly constant in most of the South Asian countries. High out of pocket expenditure results in financial burden, inadequate access to health care, health inequities. South Asian governments, on average, invest less than 1% of their GDP on health expenditure, placing the region behind others in terms of health investment (Ahmed et al., 2019). According to the World Bank, between 2011 and 2014, healthcare expenditure as a percentage of GDP in South Asian countries ranged merely between 2.8% and 3.1%, with the highest expenditure observed in Southeast Asia. This trend underlines a glaring absence of well-defined and strategic health policies, leading to sluggish sustainable development in the healthcare sector.

Presently, South Asia is weathering an unprecedented confluence of financial disruptions due to the economic crisis in Sri Lanka, floods in Pakistan, war repercussions from Ukraine, and lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite these challenges, the region’s growth averaged 5.8% in 2022, down from 7.8% in 2021, largely buoyed by the exports and services sector of India and tourism in Maldives and Nepal. Despite this economic growth (Figures 3 & 4), healthcare systems in the region grapple with a multitude of challenges. A closer look at the healthcare expenditure as a percentage of GDP in 2019 reveals that Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka invested 13.24%, 2.48%, 3.61%, 3.01%, 8.04%, 4.45%, 3.38%, and 4.08% of their total GDP, respectively, into healthcare. Averaging at 3.09%, these investments are considerably small in relation to their gross domestic products. Moreover, the pandemic crisis exposed an inequitable distribution of resources across this region, with a majority of healthcare facilities concentrated in urban and capital areas.

In conclusion, increased investment in public health, strategic planning, and targeted intervention are necessary to bridge these gaps and stimulate economic growth in the South Asian region. Healthcare services are crucial for development and wellbeing of a community and thus investment to improve the accessibility and quality of healthcare services can drive the economic growth.

The interrelation between health expenditure and economic growth has been extensively studied worldwide, yielding a variety of findings. Several studies have reported a positive impact of health expenditure on economic growth. For instance, Devarajan et al. conducted a review of 43 developing countries and found a positive correlation between public expenditure and growth [43]. Li and Huang analyzed data from China between 1978 and 2005, observing a positive impact of health expenditure on economic growth, considering real GDP growth, physical capital, and human capital [44]. Gupta and Mitra studied 15 states in India and identified a significant negative impact of health expenditures on poverty, alongside a positive impact on growth [45]. Similarly, studies conducted in Pakistan, Nigeria, and Islamic Conference member countries supported the notion that health expenditures contribute to economic growth [46-49].

Sarpong et al. examined long-term economic growth in sub-Saharan countries and reported a bidirectional causal relationship between health and economic growth [50]. Rana et al. constructed a model using OECD data, revealing a significant positive impact of health expenditure and health system performance on national growth [51]. Khan et al. analyzed the countries of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and observed a unidirectional causal relationship from healthcare expenditure to economic growth [52]. Sethi, et al. conducted a study among South Asian countries, reporting a bidirectional causal relationship between health investment and economic growth [53]. However, it is essential to note that conflicting findings also exist. Sen et al. examined the causal effect of health and education investments on economic growth in eight developing countries, finding mixed results. Brazil and Mexico demonstrated a causal impact of health expenditure on economic growth, while Indonesia showed a negative relationship, and the remaining countries did not show any association [54].

Halici-Tuluce et al. analyzed countries of various income levels, discovering a bidirectional negative relationship between health expenditure and economic growth [55]. Similarly, Eggoh et al. studied African countries and observed a negative impact of public health expenditures on economic growth [56]. These diverse findings emphasize the complex nature of the relationship between health expenditure and economic growth. Factors such as country-specific characteristics, policies, and contextual elements should be considered when interpreting these results. Nonetheless, investing in health is crucial for overall societal well-being and has the potential to contribute positively to economic growth.

Investigations into the impact of health investment on economic growth have yielded mixed findings. Different studies have highlighted both positive and negative impacts of public health expenditure, emphasizing the importance of effective and strategic allocation of resources. To ensure positive outcomes from public health investment, it is crucial to prioritize equity and necessity. Additionally, measures such as controlling corruption, enforcing laws, ensuring political stability, and implementing strong supervision and planning mechanisms are essential. South Asian countries have made some progress in their health systems over the past decades, although several challenges persist. The region is currently grappling with an ongoing economic crisis in the aftermath of the pandemic. Therefore, investing in public health with equity and fairness can serve as an additional strategy to stimulate economic growth. There are significant opportunities for improvement in the health sector, which can enhance the quality of life, life expectancy, mortality and morbidity rates, and reduce financial burdens related to healthcare. Consequently, investing in public health can also enhance the capacity and productivity of the labor force, leading to overall economic growth.

However, prior to making expenditures or investments, it is crucial to conduct a comprehensive situation analysis and develop investment plans based on the specific requirements, available resources, and political stability of each country. This review suggests that by prioritizing and allocating higher expenditures to improve public health management, the South Asian region has the potential for overall economic expansion. Governments in the region should strive to achieve universal health coverage for all residents through careful monitoring of the regional context and taking appropriate steps accordingly. Enhancing the overall health status of the population in the region can significantly contribute to economic growth and prosperity.