Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Adewale Lawrence*

Received: March 18, 2024; Published: April 02, 2024

*Corresponding author: Adewale Lawrence, Bioluminux Clinical Research, 720 Brom Drive, Suite # 205, Naperville, Illinois 60540, United States

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.55.008772

Background: Achieving equitable healthcare access remains a global challenge, particularly in rural areas such as in Nigeria. This study addresses the persistent disparities in healthcare access and utilization by examining factors such as distance to hospitals, occupation type, road infrastructure, and geographical location in rural Nigeria.

Objective: The primary objective of this study is to investigate the influence of distance, occupation type, road infrastructure, and geographical location on healthcare access and utilization in rural Nigeria. Additionally, the study aims to assess the relationship between these factors and individuals' ability to effectively communicate with healthcare providers.

Methodology: Employing a descriptive survey research design, data were collected from primary healthcare stakeholders in the Itele community, Ado-Odo local government area, Nigeria. A total of 40 participants, including healthcare staff and users, were sampled using purposeful sampling techniques. Data analysis involved chi-square tests and cross-tabulation analyses to explore associations between variables.

Results: The study revealed that distance to hospitals significantly affects healthcare access, with individuals residing farther reporting greater challenges. Occupation type was found to influence perceptions of drug affordability, highlighting socioeconomic disparities in healthcare. However, road infrastructure did not significantly impact hospital choice, contrary to expectations. Geographical location showed no substantial effect on communication with healthcare providers.

Discussion: The findings underscore the importance of proximity to healthcare facilities in ensuring timely access to treatment. Addressing socioeconomic disparities and improving infrastructure are crucial for enhancing healthcare access in rural Nigeria.

Keywords: Healthcare Access; Rural Healthcare; Nigeria; Distance; Occupation; Road Infrastructure; Communication with Healthcare Providers

The aspiration for "Health for All" by 2020 has long been a global objective, yet its realization remains elusive, especially in rural and remote regions where a significant portion of Nigeria's population resides. A 2014 report by the RUPRI Health Panel delved into this issue, offering insights into the definitions and measures of healthcare access, particularly in rural settings. In Nigeria, where rural populations constitute a substantial proportion of the country's demographic landscape, addressing healthcare disparities in these areas is imperative for advancing the nation's overall health outcomes and fulfilling the vision of equitable healthcare for all. It explores the persisting challenges of healthcare access in rural Nigeria, drawing from the backdrop of the unattained "Health for All" goal and the insights provided by the RUPRI Health Panel report [1] Rural residents face barriers to accessing essential healthcare services like primary care, dental care, and behavioral health due to factors such as workforce shortages, insurance status, and stigma. Despite available services, belief in receiving quality care remains a challenge [2]. Health outcomes, like infant mortality rates (it is the number of babies who die before the age) of one per thousand live births per year, are typically worse in rural areas compared to urban areas, exemplified by Nigeria's 2019 infant mortality rate of 74.2 deaths per 1000 live births, with rural rates higher at 70 to 49 deaths per 1000 live births [3].

With a 13% immunization rate for children between 12-23 months, Nigeria is the African country with the lowest vaccination rate. The substantial presence of Acute Respiratory Infections and diarrhea also contribute to the elevated mortality rates for children all these were a result of not being able to pay bills [4] Infant mortality rate shows how countries' survival rates vary due to different stages of development [5]. Rural infants in Nigeria face higher mortality due to limited healthcare access. Challenges like financial constraints and distance to facilities hinder maternal care, contributing to preventable neonatal deaths. Targeted efforts, outlined by WHO, are crucial for addressing rural health disparities and breaking the poverty-health cycle [6]. Access remains a major rural health issue globally, with shortages of healthcare professionals and emergency services posing challenges [7]. In rural areas, ensuring healthcare availability is vital for community security [8]. Health services in rural and remote areas face challenges due to limited funding and resources. Developing countries grapple with poverty and scarce healthcare facilities, while developed nations witness a trend of reduced support for rural health services amid broader economic and social changes, contributing to rural decline [9].

With the exception of public health or specific disease experts, there has been minimal medical input in the development of the majority of the World Health Organization and other primary healthcare initiatives worldwide. Doctors in particular have not often been involved in implementation in the field [10]. As the primary providers of basic medical care, family the family physician sees the patients in their medical practice as a "population at risk" in order to provide patient-oriented, community-focused preventative care [11]. Family practice is essential for health system development, per the World Health Assembly. A full health team, including doctors, nurses, medical assistants, and village health workers, is crucial for addressing community health needs. Active community involvement is vital for achieving the vision of primary healthcare and optimizing health system effectiveness [12]. In Nigeria, the decline in infant and under-five mortality rates has been slower than anticipated, with reductions of 21% and 34%, respectively, from 1990 to 2013. Despite efforts to meet Millennium Development Goal targets, Nigeria fell short and lagged behind peer countries like Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, and Senegal. Financial access poses a major challenge, with high costs for primary healthcare visits relative to people's income levels. While geographic access to public PHC facilities is relatively good, the private sector, particularly Patent and Proprietary Medicine Vendors (PPMVs), plays a significant role in healthcare provision. However, there are issues with delayed and informal referrals and variable service quality. Shortages of essential drugs, vaccines, and medical equipment, coupled with deficient infrastructure, hamper the effectiveness of PHC facilities. Addressing these challenges is crucial to improving the quality and accessibility of primary healthcare services in Nigeria [13].

The country boasts a dense network of PHC facilities, with 18 facilities per 100,000 people, higher than in comparison countries [14]. However, despite this seemingly robust infrastructure, the actual number of public health clinics and posts falls below national targets [15]. The workforce density exceeds the African country average, yet there's a mismatch between trained health workers and their deployment, resulting in limited attention to health promotion and prevention. Supply chain inefficiencies and fragmented systems present additional challenges for PHC facilities, with as many as five uncoordinated supply channels. In terms of financing, Nigeria's health expenditure is relatively low, primarily financed through out-of-pocket payments. Government expenditure on healthcare is limited, leading to an overreliance on user fees, exacerbating financial barriers to access. The flow of public finance is fragmented across federal, state, and local government levels, with uncertain funding flows hindering PHC financing. Most funding is directed towards health worker salaries, leaving minimal resources for essential supplies and infrastructure. There's a heavy reliance on cost recovery mechanisms such as revolving drug funds, which often fail to ensure sustainable drug supplies and contribute to high user fees. Governance structures in Nigeria's primary healthcare (PHC) system are highly fragmented, posing significant challenges to effective service delivery. At the federal level, the Ministry of Health oversees policy direction, with specific responsibilities divided between the Minister of State for PHC and the Minister of Health. The National Primary Health Care Development Agency implements policies in coordination with the Ministry of Health. At the state level, authority over health policy and financing lies with the state governor, while the State Ministry of Local Government Affairs manages and pays high-level PHC staff. The State Ministry of Health has limited power, with funding controlled by the State Ministry of Local Government [16].

Local government chairmen oversee PHC departments and control local budgets with the LGA PHC coordinator responsible for program management [17]. However, coordination between state and local levels is often lacking, leading to inefficiencies in resource allocation and service delivery. Community involvement is facilitated through ward and village development committees, but their effectiveness varies. These governance challenges contribute to inefficiencies in human resource deployment and management, with well-trained health workers often underemployed or inadequately supervised. Performance management mechanisms are lacking, resulting in low productivity and poor quality of care. Weak incentives further compound these issues, with limited supervision exacerbating the problem. Benchmarking Nigeria's PHC performance against other African countries reveals significant disparities. While Nigeria has the largest density of medical facilities and healthcare professionals, but it also has the lowest infrastructure, medicine access, and diagnosing precision. Poor service delivery metrics include absenteeism rate and amount of time invested to patients. Nigeria also has the highest under-five death rate and the lowest vaccination coverage. Nigeria has enacted legislative reforms, such as the Primary Health Care under One Roof (PHCUOR) policy, which aims to combine PHC services under a single authority, to address these issues. To enhance funding, the National Health Act of 2014 creates a basic health care provision fund. Both the SOML—P4R project and results-driven financing are promising initiatives aimed at enhancing service delivery and coordinating state initiatives with federal objectives [18].

In our study to assess primary healthcare (PHC) performance in Nigeria, we leverage a diverse array of data sources. These include Demographic and Health Surveys (USSAID, 1996-2014) for outcome indicators, the Nigeria General Household Survey (Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics, 2010-2014) for PHC access, and the World Development Indicators (World Bank Database, 2016) for poverty headcount. We also utilize the WHO National Health Account (WHO, 2016) for financing data, the WHO Global Health Workforce statistics (WHO, 2014) for health worker density, and the Advancing Child Health via Essential Medicine Vendors survey (Global Health Group, 2014) for Patent and Proprietary Medicine Vendors (PPMVs) data. Moreover, we heavily rely on the Nigeria Service Delivery Indicator survey (World Bank, 2012-2014) to gain insights into health facilities, allowing for comparisons between Nigeria and other countries. Provider ability is assessed using clinical vignettes, and national- and state-level averages are generated from data collected in 12 surveyed states. Despite limitations in national representativeness due to the survey's focus on a subset of states, high levels of intrastate facility sampling enable quality interstate comparisons within Nigeria.

The study's relevance lies in the fact that, according to Strasser R, et al. (1998), significant and proactive participation from the community is necessary for the primary healthcare system to realize its mission. Where there is active community engagement, healthcare systems function best. The involvement of the community will go a long way to sensitize the rural dwellers to the need to take health issues seriously and even make a representation to the government of the need to reduce the cost of medical care so that health care services can be made available to the populace.

1. To determine whether residents in rural areas can afford the costs of their medical care.

2. To figure out how to go to and make use of amenities, such as transportation to those that could be far away.

3. To discover whether the participants feel confident in their capacity to interact with medical professionals, especially in cases when the patient lacks medical education or speaks English as a second language.

4. To check whether people believe they may utilize services without jeopardizing their privacy.

5. To find out if the rural dwellers believe that they will receive quality health care.

6. Apart from primary health care are their general hospitals around us.

1. How will distance affect those who go to the hospital for treatment?

2. Can the type of work one does influence his ability to pay for drugs in the hospital?

3. Do the available roads affect the type of hospitals people use?

4. Can the years of experience on the job help to communicate well with health officials?

Research Design

This study is a descriptive survey research design that is used to determine if the cost of paying for health bills has an impact on the health and well-being of rural dwellers in Nigeria using a questionnaire.

Population of the Study

This study examines primary healthcare in the Itele community, Ado-Odo local government area, Nigeria. Forty questionnaires were distributed: 20 to primary healthcare staff and 20 to users. Data collection spanned five weeks, employing purposive sampling. All data were sourced directly from primary healthcare stakeholders.

Sample and Sampling Method

In order to identify and choose scenarios packed with data and make the most use of few resources, purposeful sampling is a strategy that is frequently employed in qualitative research (Patton 2002). This entails locating and picking people, or groups of people, who have firsthand experience with or exceptional understanding of an interesting phenomena [19]. Bernard (2002) and Spradley (1979) highlighted the significance of availability and desire to engage, as well as the capacity to explain, express, and reflect when communicating views and opinions, in addition to knowledge and experience [20]. By reducing the possibility of selection bias and accounting for the possible effect of known and unknown confidence, probabilistic or random sampling, on the other hand, ensures the generalizability of results [21].

The data collection instrument for this study is a questionnaire divided into two sections. Section I collects respondents' personal information, while Section II comprises twenty items assessing respondents' views on the impact of cost on the health and well-being of rural dwellers in Nigeria. The questionnaire utilizes a 4-point Likert scale ranging from "Strongly Agree" to "Strongly Disagree."

Methods of analyses that would be used for the hypotheses are the Chi-square is useful with data in the form of frequencies i.e. data based on a nominal scale of measurement such as representing religious affliction, qualification, parental occupation, opinion about a phenomenon, etc.

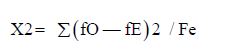

By definition, the Chi-square is given by:

Where X2 = (pronounced high)

∑ = summation

Fo = observed frequency

Fe = expected frequency

Also, Df= degree of freedom = (c-1) (r-1)

Where c= number of columns and

r= number of rows

The interpretation of Chi-square is dependent on the required level of significance, which is determined by the nature and use of research, and the size of the degree of freedom involved, which is determined by the dimension of the contingency table. These two are used in the location of the critical (standard) value relative to the significance level and the degrees of freedom on the table were compared with the observed (calculated) value. (Sanni R.O.2007).

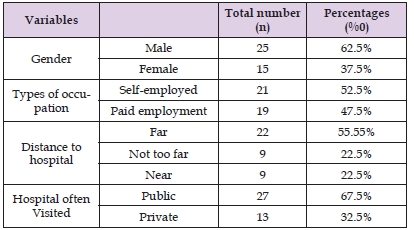

Table 1

Frequency and percentages of Gender, Types of occupation, Distance to hospital, and Hospital often visited: The demographic distribution of the study's participants, including gender, occupation type, distance to hospital, and frequency of hospital visits. The study included 40 individuals, with a gender distribution of 62.5 percent males and 37.5% females. In terms of their occupation, the majority of participants (52.5%) were self-employed, with the remainder (47.5%) working for a salary. The distance to the hospital differed among participants, with the majority living far away (55.55%), followed by those living close by (22.5%), and those at a moderate distance described as "not too far" (22.5%). Furthermore, participants' hospital visiting habits were analyzed, which indicated that a higher number of participants regularly attended public hospitals (67.5%) than private healthcare facilities (32.5%).

Table 1: Frequency and percentages of Gender, Types of occupation, Distance to hospital, and Hospital often visited.

Table 2

Frequency and number of responses to individual questions: Survey responses on healthcare access and utilization provide attention to many aspects of healthcare-seeking behavior and physical barriers among research participants. The majority of respondents took a proactive attitude to obtaining medical assistance while sick, with 47.5% agreeing and 32.5% strongly agreeing with the statement. However, in terms of transportation facilities, none of the respondents strongly agreed that they have good roads going to hospitals, with 40% disagreeing and 47.5% strongly disapproving. Furthermore, a sizable proportion (55%) indicated unhappiness with the availability of healthcare centers in their area, indicating perceived inadequacy in healthcare facility distribution. Regarding medicine access, the majority (62.5%) reported that drugs are not always available in hospitals when seeking treatment, demonstrating potential issues in medication supply chains. The affordability of pharmaceuticals appeared as a significant concern, with all respondents expressing disagreement with the cost of drugs in hospitals. Despite a significant proportion (37.5%) reporting excellent communication with health officials, a lesser amount (10%) expressed discontent, emphasizing possible areas of development in healthcare providers. -Patient communication

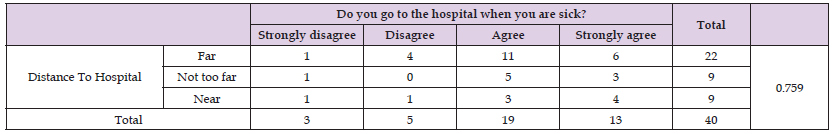

Table 3

Distance To Hospital *Do you go to the hospital when you are sick? Cross tabulation and P-Value: The findings of a cross-tabulation analysis, which investigates the association between two categorical variables: distance to the hospital and people's tendency to seek medical care while sick. The cross-tabulation provides a comparative investigation of how people's healthcare-seeking behavior varies with their distance to the hospital. For example, it demonstrates that among those who live far from hospitals, 11 agree and 6 strongly agree to seek medical care when they are ill, demonstrating that a sizable proportion of people are willing to seek healthcare regardless of the distance. In contrast, among those residing near hospitals, 7 agree and 4 strongly agree, indicating a significantly higher tendency for seeking medical care among those in close vicinity to healthcare facilities p-value of 0.759 indicates that there is no statistically significant relationship between distance to the hospital and persons' probability to seek medical care while ill. As a result of this p-value were unable to reject the null hypothesis, which states that there is no association between hospital distance and healthcare-seeking behavior.

Table 3: Distance To Hospital *Do you go to the hospital when you are sick? Cross tabulation and P-Value.

Table 4

Types Of Occupation *Are the drugs available affordable? Cross tabulation and P-value: The table suggested the association between different occupations and people's opinions of drug affordability. The responses are divided into two categories of occupation: self-employment and paid work. Respondents in each category indicated their views on medicine affordability, which were classified as Strongly Disagree, Disagree, or other non-table comments. With investigation, it is evident that among self-employed individuals, 16 strongly disagree and 5 disagree with the belief that pharmaceuticals are affordable, for a total of 21 replies. In contrast, among those in paid employment, 9 strongly disagree and 10 disagree, for a total of 19 replies. The p-value of 0.06 suggests that there is no statistically significant relationship between occupation types and perceptions of drug affordability. In this case, the p-value indicates a statistically non-significant association between the variables. Particularly the observed association between occupation types and perceptions of drug affordability seems to have occurred by chance.

Table 5

Hospital Often Visited *Do you have good roads where vehicles can fly to the hospital? Crosstabulation and P-value: The relationship between the frequency of hospital visits (categorized as public or private hospitals) and individual evaluations of the road quality moving to the hospital. On inspection, that finds frequently visited public hospitals, 11 people strongly disagree, 12 disagree, and 4 agree that there are good roads to the hospital, totaling 27 responses. In contrast, among those who usually visit private hospitals, 8 strongly disagree, 4 disagree, and 1 agree, a total of 13 responded. The p-value of 0.457 indicates a level of statistical significance in the link between hospital visit frequency and assessments of road conditions. This p-value implies that there is no statistically significant relationship between the variables.

Table 5: Hospital Often Visited *Do you have good roads where vehicles ply to the hospital? Crosstabulation and P-value.

Table 6

cross-tabulation between communication response with all variables and individual P-value: The table indicates cross-tabulated data that investigates the relationship between respondents' capacity to interact effectively with health professionals and several demographic parameters such as occupation type, distance to the hospital, frequency of hospital visits, and gender. Among self-employed people, 11 disagreed and 7 agreed on the ability to communicate effectively, whereas salaried employees disagreed and agreed. Notably, there was no significant relationship between profession type and communication skill, as evidenced by the p-value of 0.537. Comparably there was no significant relationship identified between distance to the hospital, hospital visit frequency, gender, and communication skills (p-values of 0.674, 0.72, and 0.108, respectively).

The study included 40 individuals and investigated various aspects of healthcare access and utilization. The major findings revealed a higher percentage of males (62.5%) compared to females (37.5%), with the majority being self-employed (52.5%) and living far from hospitals (55.55%). Near Significant associations were observed between occupation types and perceptions of drug affordability (p-value = 0.06), highlighting a potential area of concern. Additionally, while public hospital visitors expressed dissatisfaction with road conditions, there was no statistically significant relationship between hospital visit frequency and assessments of road quality (p-value = 0.457). Distance has an important effect on individuals seeking hospital treatment, indicating that individuals living farther away may face challenges to healthcare access. This perspective corresponds with broader conversations about inequalities in healthcare, particularly in marginalized regions where mobility challenges aggravate underlying disparities in healthcare. Individuals who face difficulties with transportation frequently have a higher disease burden, showing a complicated interplay between socioeconomic variables, healthcare access, and health outcomes. Recognizing these discrepancies allows healthcare organizations to better serve patients' complex demands and adopt specific strategies that reduce the impact of distance and transportation obstacles on healthcare access. Wallace R, Hughes-Cromwick P, Mull H, and Khasnabis S show that transportation is a fundamental but essential step for continued provision of quality health care and pharmaceutical access, especially for patients with chronic disease [22].

Hypothesis Two

Research findings contradicted the null hypothesis, which suggested that occupation had no significant effect on medicine affordability. Contrary to the expectation, the research indicated a significant influence of work on people's ability to pay for medications, emphasizing socioeconomic gaps in healthcare access. This emphasizes the significance of the profession as a predictor of healthcare affordability, with implications for equal access to vital pharmaceuticals. According to De La Torre, a person can be in debt for a long time if not being able to pay for healthcare bills promptly [23]. In the first part of 2020, according to a report by the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), 9.7%, or 31.6 million adults (of all ages), lacked health insurance. Survey findings showed that the uninsured rate and number of uninsured decreased from 2019 (10.3% or 33.2 million people of all ages) but the difference was insignificant [24].

Hypothesis Three

The study of the association between hospital type and road infrastructure revealed insufficient data to reject the null hypothesis. Despite expectations for considerable benefits, the investigation found that the quality of road infrastructure has no meaningful influence on hospital choice. This suggests that road conditions are not what significantly influence people's hospital selection decisions, stressing the importance of other factors in healthcare decision-making. Alvin, a patient having end-stage pulmonary fibrosis who was critically sick, was admitted to the facility in June 2011 due to pneumonia. Alvin was given 100% oxygen, strong antibiotics, and steroids by his doctor, a pulmonologist at an elite academic medical facility, but his health rapidly worsened. Since patients have discovered that they can also get treated elsewhere apart from government hospitals they used any hospital of their choice [25].

Hypothesis Four

The study supported the null hypothesis, which suggested that location had no significant effect on communication with health professionals. Despite apparent assumptions about regional effects on communication, the data showed that an individual's location had no substantial impact on their capacity to communicate successfully with health officials. This emphasizes the need to take into account elements other than geographical location when evaluating communication dynamics in healthcare systems. COVID-19 e-learning showed that location does not have any barrier to being able to join the class network is available (Zalat MM, Hammed MS, Bolbol SA,2021) [26].

The study suggests that living far from hospitals may pose a significant barrier to accessing treatment, highlighting the importance of proximity to healthcare facilities in ensuring timely and effective care. Secondly, occupation type emerges as a determinant of drug affordability, indicating that individuals' economic circumstances influence their ability to afford essential medications. Thirdly, the research underscores that the availability of road infrastructure does not necessarily dictate the choice of a healthcare facility, emphasizing other factors at play in hospital selection. Finally, the study suggests that geographical location does not inherently impact individuals' ability to communicate effectively with health officials, challenging assumptions about the influence of location on healthcare communication.

The following recommendations are necessary for patients to follow so that they can have access to healthcare:

1. Hospitals should be built closer to the rural dwellers so that they can have access to treatment when they are ill.

2. The populace should be encouraged to engage in health insurance to access health bills.

3. The government should subsidize the cost of the tests and drugs used for treatment in hospitals in rural settings.

4. There should be a proper road network in the rural setting, that will go a long way to assist the rural dwellers to access health care.

5. When the above points are carried out, it is believed that rural dwellers will be able to pay off their bills with ease.