Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Pablo Rosser1* and Seila Soler2

Received: March 04, 2024; Published: March 21, 2024

*Corresponding author: Pablo Rosser, International University of La Rioja, Logroño, Spain. Avenida de la Paz, 137, 26006 Logroño, La Rioja, Spain - Faculty of Education, Spain

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.55.008739

This pilot study, preceding a broader investigation into the entire older adult student body at the Permanent University for Adults in Alicante, Spain, explores the impact of lifelong learning on their emotional wellbeing. It seeks to identify key factors influencing their emotional states and overall well-being through the educational programs provided. Utilising descriptive and quantitative research methods, including the Ryff Scales of Well-being and Mood, this study offers a comprehensive analysis of the well-being profile of this demographic group. Findings emphasise the significance of future planning, seeking new experiences, and perceiving personal improvement in enhancing life satisfaction and self-efficacy among older learners. Furthermore, the research underscores the necessity for pedagogical adaptations to promote a proactive attitude, self-efficacy, and autonomy, ultimately contributing to improved quality of life and personal satisfaction for older adults engaged in lifelong learning. These insights pave the way for more effective and empathetic educational strategies, tailored to the unique needs of older learners. This study, preceding a broader investigation into the entire older adult student body at the Permanent University for Adults in Alicante, Spain, explores the impact of lifelong learning on their emotional well-being. It seeks to identify key factors influencing their emotional states and overall well-being through the educational programs provided. Utilising descriptive and quantitative research methods, including the Ryff Scales of Well-being and Mood, this study offers a comprehensive analysis of the well-being profile of this demographic group. Findings emphasise the significance of future planning, seeking new experiences, and perceiving personal improvement in enhancing life satisfaction and self-efficacy among older learners. Furthermore, the research underscores the necessity for pedagogical adaptations to promote a proactive attitude, self-efficacy, and autonomy, ultimately contributing to improved quality of life and personal satisfaction for older adults engaged in lifelong learning. These insights pave the way for more effective and empathetic educational strategies, tailored to the unique needs of older learners.

Keywords: Lifelong Learning; Older Adults; Emotional Well-Being; Pedagogical Adaptations; Self-Efficacy

The concept of active aging is positioned as fundamental [1-4], even in aspects such as gamification [5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines it as the process of optimizing health, participation, and security opportunities to enhance the quality of life as people age [6,7]. This concept is closely related to psychological and social well-being, emphasizing the importance of social integration, active participation, and continuous learning [8]. Psychological well-being in older adults [9] encompasses multiple dimensions, including autonomy, personal growth, mastery of the environment, positive relationships with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. These dimensions are significantly affected by factors such as education and lifelong learning [10]. Likewise, social well-being, which involves the quality of relationships and social integration, is crucial in this age group [11]. Education, in this sense, not only acts as a tool for cognitive development but also as a means to enhance social interaction and community integration. Quality education for older adults is an essential aspect within the framework of active aging. This education should not only focus on knowledge acquisition but also on promoting psychosocial well-being, adapting to the specific needs of this group [12]. The relevance of adaptive education lies in its ability to address the unique challenges faced by older adults [13], including changes in health, the transition to retirement, and the search for purpose and meaning at this life stage [14].

General Objective

To investigate and analyze the interconnection between well-being and emotions of older adults attending the Permanent University for Adults in Alicante (Spain) (UPUA), with the purpose of identifying essential factors that explain the influence of the training provided on their emotional state and well-being. Additionally, this study aims to determine possible pedagogical adaptations that could enhance their quality of life and personal satisfaction.

Specific Objectives

To describe in detail the well-being profile of the older adult population by applying statistical analysis, specifically measures of central tendency and dispersion, on the data collected in the well-being survey.

Research Hypotheses

• H0: No statistically significant variations are observed in the

self-reported well-being levels when comparing different categories

within the selected sample.

• H1: Statistically moderate differences in the perception of

well-being are recorded among the students under study.

• H2: Statistically significant differences in the perception of

well-being are identified among the students under study.

Study Methodology

This pilot study is structured as a descriptive and quantitative research, which has a preliminary advancement (deleted for anonymity) and is part of a broader research to be developed with a much larger spectrum of students (deleted for anonymity). The main tool used was a questionnaire based on the Ryff Scales of Well-being and Mood [9,15-27]. A descriptive and frequency analysis was performed, incorporating measures of central tendency and dispersion, to examine the responses in relation to the different items of the Well-being Scale. This analysis will focus on the distribution of responses, identification of patterns therein, interpretation of findings, their significance for psychological well-being, and in formulating pedagogical recommendations based on these results.

Study Sample

The study sample consists of older adults enrolled in online educational programs at UPUA. For this pilot phase, 15 individuals from a course taught by one of the researchers on the History of Spain through poison participated. Participation was completely voluntary and anonymous, without external incentives. Informed consent was obtained that explained the objectives, potential risks, contact information of the researchers and the institution, as well as the benefits of participating in the study, thus ensuring the autonomy and protection of the personal data of the participants in accordance with data protection regulations. No specific exclusion criteria were applied, to obtain a diverse and representative sample of the target population, which is key to the generalization and relevance of the study results.

Evaluation Tools

A single questionnaire, previously validated and used in educational research, considered a reliable and valid instrument for evaluating students according to the research objectives, was used. The administration of the questionnaire, which is central to the evaluation, had an approximate duration of 20 to 30 minutes at the beginning of the classes. Each item was designed to correspond with a specific dimension of the survey, and relevant statistical analyses were applied to examine the relationships between these variables and others in the study. The selected instrument was, as mentioned, the Ryff Psychological Well-being Evaluation Questionnaire [9], recognized and validated in the scientific literature, with the necessary adaptations [21,28,29]. For the analysis of well-being and mood, the responses from the Ryff questionnaire were used. Each item was linked to a specific dimension of well-being or mood. The responses were analyzed using 6-point Likert scales, ranging from 1 (not at all agree) to 6 (absolutely agree). The analysis, in this second phase of this pilot study, included the comparison of levels of well-being and mood of the participants, and the exploration of other variables relevant to the study.

Data Analysis Procedure

A Descriptive Analysis was carried out, which included obtaining measures of central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion (standard deviation, range) for each item of the survey. This analysis is essential to assess the quality of the collected data, including the identification of missing values and atypical responses, and provides a basic understanding of the characteristics of the collected data.

Item Analysis

Items were examined in comparison with their opposing equivalents to identify the most significant contrasts. These antagonistic relationships illustrate how different aspects of the attitudes and perceptions of older adults may conflict or not fully align with each other. These discrepancies, therefore, offer a more nuanced view of their psychological and social well-being. In each case, the prevailing proportions were analyzed, and the inherent variability was explored. This process is crucial for a deep understanding of the psychological well-being of the studied sample. Based on the results, relevant recommendations were formulated to implement formative strategies in the educational field, optimize the learning experience, and promote psychological well-being in the classroom.

Future Planning (Item 6), Having New Experiences (Item 35), and Lack of Personal Improvement (Item 36): First, we will analyze the responses to the statement of item 6 (“I enjoy making plans for the future and working to make them a reality”). All respondents (100% adding categories 4, 5, and 6) show a considerable degree of enjoyment in making plans for the future and working towards their realization (Figure 1). Regarding Psychological Well-being, having future goals and enjoying the planning and realization process is important, as it contributes to a sense of purpose and direction in life. Enjoying planning and achieving goals is related to greater self-efficacy and personal satisfaction. Considering the unanimity in response, the focus in student training could be on maintaining and enhancing this proactive attitude. That is, to continue encouraging planning and a proactive attitude, as well as providing tools and resources that aid in the effective realization of plans. Next, we will analyze the responses to the statement of item 35 (“I think it is important to have new experiences that challenge what one thinks about oneself and the world”). The majority of respondents (73.3% adding categories 5 and 6) consider it very important to have experiences that challenge their perceptions, while 26.6% (adding categories 3 and 4) value these experiences as moderately or quite important. These results suggest that most respondents value self-exploration and, relevant to our research, continuous learning through new experiences that challenge their view of the world and themselves. Regarding Psychological Well-being, seeking new experiences that challenge what one thinks is crucial, as it fosters mental flexibility and adaptability. Valuing these experiences is related to resilience and openness to new ideas and perspectives.

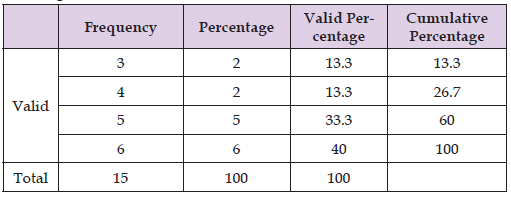

For those with a moderate rating, it could be beneficial to promote in training the benefits of learning and self-exploration through new experiences (Table 1 & Figure 2). Lastly, we will analyze the responses to the statement of item 36 (“When I think about it, I really haven’t improved much as a person over the years”). A majority of respondents (60% adding categories 1 and 2) disagree with the idea that they have not improved much as people over the years, while 33.3% of respondents (adding categories 4 and 5) somewhat agree that they have not improved much as people. There is variability in the perception of personal growth, which may reflect different experiences, expectations, and levels of self-awareness. Regarding Psychological Well-being, the perception of improvement and personal growth is important, as it contributes to self-esteem and life satisfaction. For those who feel stuck in their personal growth, identifying areas of improvement and setting clear goals can be beneficial. For those who feel they have not improved much, it would be useful to focus on training in the classroom on strategies for personal development and self-awareness. Encouraging personal reflection, goal setting, and continuous learning can help improve the perception of one’s personal growth (Table 2). The analysis of items related to future planning, new experiences, and personal improvement offers a nuanced view of the psychological well-being of older adults. While item 6 reveals a proactive attitude towards the future, item 35 shows the valuation of new experiences for personal growth, and item 36 reflects varied perceptions of personal development over the years. These findings suggest the need for personalized educational training that recognizes both strengths and potential growth areas, thus comprehensively addressing the psychological and social well-being of older adults (Figure 3).

Table 1: Item 35. I think it is important to have new experiences that challenge what one thinks about oneself and the world.

Note: Source: Own elaboration

Note: Source: Own elaboration

Relationship between Self-Confidence (Item 7), Willingness to Change (Item 39), and the Influence of External Opinions (Item 33): First, we will analyze the responses to the statement of item 7 (“In general, I feel confident and positive about myself”). A significant majority of respondents (86.6% adding categories 4, 5, and 6) show a considerable degree of agreement with feeling secure and positive about themselves, though 13.3% of respondents (category 2) indicate little agreement with feeling secure and positive (Figure 4). Regarding Psychological Well-being, feeling secure and positive is fundamental, as it contributes to good mental health and healthy interpersonal relationships. A positive self-image is related to greater resilience and a better ability to manage adversities. For those who feel less secure and positive, it could be beneficial in training to explore strategies to strengthen self-esteem and self-acceptance. Next, we will analyze the responses to the statement of item 39 (“If I were unhappy with my life situation, I would take the most effective steps to change it”). A significant majority of respondents (66.7% adding categories 5 and 6) show a high or very high willingness to take effective measures to change their life situation if they feel unhappy. A 33.3% of respondents (adding categories 2 and 4) indicate a lower or moderate willingness to make changes. Regarding Psychological Well-being, the ability and willingness to change unsatisfactory situations are important, as they reflect personal agency and self-efficacy. Finding a balance between accepting circumstances and the willingness to make changes is crucial for mental health. For those with less willingness, it may be useful to develop in training strategies that increase confidence and self-efficacy, thus facilitating the ability to change unsatisfactory situations.

In this sense, promoting adaptability, planning, and problem-solving skills can be beneficial for those looking to improve their willingness to change (Table 3 & Figure 5). Lastly, we will analyze the responses to the statement of item 33 (“I often change my decisions if my friends or family disagree”). A majority of respondents (53.3% adding categories 3, 4, and 5) show a moderate to high tendency to change their decisions if their friends or family disagree, while 33.4% of respondents (adding categories 1 and 2) indicate they rarely or unlikely change their decisions based on others’ disagreement. Regarding Psychological Well-being, finding a healthy balance between considering others’ opinions and maintaining personal autonomy is important. For those who often change their decisions based on others, it may be useful to develop in classroom training skills of self-assertion and confidence in their own choices (Table 4 & Figure 6). The exploration of responses to items on self-confidence, willingness to change, and the influence of external opinions in older adults reveals a complex interaction of factors affecting their psychological and social well-being. While the majority show high self-confidence and willingness to change, some are susceptible to external influence, suggesting a potential conflict between self-confidence and adaptability to others’ opinions. These results underline the importance of a holistic approach in the education of older adults, considering the interconnection of different attitudes and perceptions to promote an integral and sustained well-being (Figure 7).

Relationship between Satisfaction with Home (item 11) and Lack of Close Relationships (Item 26): First, we will analyze the responses to the statement of item 11 (“I have been able to build a home and a way of life to my liking”). A significant majority of respondents (66.7% adding categories 5 and 6) feel very or extremely satisfied with the home and way of life they have built, although 33.3% of respondents (adding categories 2, 3, and 4) show a lower degree of satisfaction. The variability in responses may reflect different personal circumstances, priorities, and available resources (Figure 8). In the radar chart illustrating the relationship between satisfaction with home life and the lack of close relationships, it is shown how both aspects have a similar level of satisfaction/agreement among respondents, with 66.7% satisfaction or disagreement with the lack of close and trusting relationships. Regarding Psychological Well-being, being satisfied with one’s home and way of life is crucial for overall well-being, as it contributes to a sense of security, comfort, and belonging. The ability to create an environment and lifestyle in accordance with personal tastes is related to autonomy and the achievement of personal goals. For those with a lower degree of satisfaction, it might be useful in training to explore strategies to improve their domestic environment and lifestyle. Promoting reflection on personal priorities and providing resources or advice to improve the living environment can be beneficial for those seeking greater satisfaction in this aspect. Second, we will analyze the responses to the statement of item 26 (“I have not experienced many close and trusting relationships”). A majority of respondents (66.7% adding categories 1 and 2) disagree with the idea that they have not experienced many close and trusting relationships. A 20.1% of respondents (adding categories 4, 5, and 6) agree with the lack of close and trusting relationships. Regarding Psychological Well-being, having close and trusting relationships is fundamental. For those with limited experiences, it may be useful to foster in training social skills and opportunities to develop significant relationships (Table 5 & Figure 9). It’s important to address the needs of those lacking close relationships, possibly through social interventions or therapy. Encouraging the building of support networks and improving relationship skills can be beneficial for enhancing the quality of personal relationships. The relationship between satisfaction with the home and lack of close relationships in older adults reveals key aspects of psychological and social well-being. While satisfaction with the home implies security, comfort, and belonging, reflecting autonomy and personal achievements, close and trusting relationships contribute to emotional well-being, offering social support and emotional connection. This interaction highlights the importance of a holistic approach in the well-being of older adults, recognizing the influence of both the physical environment and social relationships, and suggests that satisfaction in one area may coexist with deficiencies in another (Figure 10).

Note: Source: Own elaboration

This research at the Permanent University for Adults in Alicante has unveiled significant aspects of the psychological and social well-being of older adults, offering an opportunity to discuss and compare these findings with similar experiences, both direct and indirect, in the field of education for older adults. The results reveal a diversity in the perception of well-being among older adults, aligning with previous studies on variations in psychological well-being in this population. While some exhibit high self-efficacy and satisfaction, others face challenges in personal growth and interpersonal relationships, reflected in the varied responses to items 35 and 36. [30-35]. The variability in the perception of well-being and the valuation of new experiences in older adults support the need for a holistic educational approach. Previous research highlights the importance of programs that integrate knowledge and skills with self-exploration, adaptability, and personal development [36-38]. Furthermore, the results suggesting the need for pedagogical strategies adapted to improve self-esteem and self-acceptance (as inferred from the analysis of item 7) are consistent with existing literature that emphasizes the role of education in enhancing the mental health and social relationships of older adults. This aligns with research that has found a positive correlation between participation in educational activities and a greater sense of self-esteem and social well-being in this population [39-42]. Also, the indication that some older adults may be less inclined to change their life situation or may be susceptible to the influence of external opinions (items 39 and 33, respectively) resonates with studies exploring resistance to change and social influence on the decisions of older adults. These studies have underscored the importance of fostering autonomy and confidence in personal decisions within educational programs for this demographic [43,44]. The discussion emphasizes the importance of tailoring education for older adults, building on previous research to enhance the effectiveness of educational programs. It highlights the need for interdisciplinary collaboration to develop inclusive educational strategies that promote the integral well-being of this population.

In this research on the well-being of older adults at the Permanent University for Adults of Alicante, various responses to specific items were analyzed to assess the proposed hypotheses. The hypothesis H0, considering the absence of significant variations in self-reported well-being, is partially supported. While certain items like future planning (item 6) indicate uniformity in responses, others such as item 35 suggest subtle differences in the perception of well-being. These variations reflect that, although there are no pronounced overall differences, there are significant nuances in specific aspects of well-being. Regarding hypothesis H1, which posits moderate differences in the perception of well-being, support is found in the variability of responses to items such as 35 and 36. These differences in the perception of personal growth and openness to new experiences indicate that there are moderate variations in how individuals experience their well-being. On the other hand, hypothesis H2, which suggests the existence of relevant differences in the perception of well-being, is partially supported by the presence of variability in responses. Although overwhelming differences are not evident, variations in certain aspects of well-being, as observed in responses to item 36, indicate that there are significant differences in certain dimensions of well-being (Figure 11). In terms of pedagogical recommendations, the findings highlight the importance of strengthening the existing capabilities and attitudes of the students, as well as addressing areas for improvement. A key strategy is to encourage a proactive attitude in the planning and achievement of objectives, providing resources that support the effective implementation of plans. This includes activities that promote self-efficacy and autonomy, enabling older adults to achieve tangible successes (Figure 12). Moreover, it is crucial to include elements that encourage learning and self-exploration through new experiences, challenging current perspectives and promoting critical thinking and creativity. For students with less personal growth or self-esteem, strategies that strengthen self-acceptance and personal reflection, encouraging self-awareness and the valuation of individual achievements, should be implemented. Training should also increase self-efficacy and promote adaptability, especially for those students with less willingness to change. Teaching problem-solving and effective planning techniques can empower students to manage and change their circumstances.

Likewise, for students influenced by external opinions, it is important to develop self-assertion skills and confidence in their own decisions (Figure 13). Finally, addressing limited satisfaction with the domestic environment or the lack of close relationships is crucial. This may include developing social skills, building support networks, and improving relational skills, in addition to fostering reflection on personal priorities and improving the living environment. These strategies will not only improve well-being in the personal and domestic sphere of students but also strengthen their sense of connection and belonging in the community. Including group activities and social skills workshops within the educational program can be key to the development of significant relationships and support for the emotional well-being of students. Together, these pedagogical recommendations, derived from an exhaustive analysis of responses to the items and aligned with the general and specific objectives of the study, highlight the need for tailored and holistic training. This approach should enhance the strengths of older adults while simultaneously addressing areas for improvement, to enhance their quality of life and personal satisfaction. The implementation of these pedagogical strategies emerges as a fundamental step towards a more effective and empathetic education for older adults, respecting their diversity of experiences and individual needs. In the exploration of well-being among older adults at the Permanent University for Adults of Alicante, this research provides nuanced insights into emotional wellness. While some aspects of well-being are uniform, others show significant variations. This study underscores the importance of adaptive learning strategies that cater to the diverse experiences of older adults, suggesting such tailored approaches can significantly benefit socio-healthcare assistance by fostering well-being that is attuned to individual needs and circumstances. These findings can guide the development of support services that enhance the quality of life for the elderly.

Deleted for Anonymity.