Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Pablo Rosser1* and Seila Soler2

Received: February 13, 2024; Published: February 23, 2024

*Corresponding author: Pablo Rosser, International University of La Rioja, Logroño, Spain. Avenida de la Paz, 137, 26006 Logroño, La Rioja, Spain - Faculty of Education, Spain

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.55.008674

This proposal for incorporating the methodology of anamnesis into the educational field, specifically aimed at the education of older adults, anticipates the implementation of a comprehensive approach that encompasses both emotional well-being and effective learning for this group. The goal is to personalize teaching and optimize the social and psychological well-being of students by adapting strategies from the medical field to pedagogy. This, in turn, aims to provide useful information to professionals in comprehensive care for older adults.

Keywords: Well-being; Emotions; Older Adults; Lifelong Learning; Statistical Analysis; Educational Anamnesis

The education of older adults faces the challenge of adapting to the needs, experiences, and expectations of a heterogeneous group that seeks not only to acquire knowledge but also to improve their emotional well-being and quality of life [1]. The incorporation of innovative methodologies that meet these requirements is crucial for the development of effective and meaningful educational programs. Moreover, this includes bridging the digital divide within this group [2]. In this context, the proposal to adapt anamnesis, traditionally used in the medical field, to the field of education emerges, creating a novel pedagogical approach called educational anamnesis.

Medical Anamnesis

Medical anamnesis, understood as the process of detailed collection

of a patient’s medical history and background, is a fundamental

practice in medicine for the appropriate diagnosis and treatment

of diseases [3-10]. Medical anamnesis is indeed a technique used

by healthcare professionals to gather relevant information about a

patient’s clinical history and medical background. The main goal of

anamnesis is to gain a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s

current medical situation and context, which assists the physician in

making an accurate diagnosis and providing appropriate treatment

[11-15]. The usual steps followed in medical anamnesis are:

• Patient Identification: The physician collects basic information

about the patient, such as name, age, gender, and occupation,

among other relevant demographic data.

• Reason for Consultation: The physician asks the patient

what the main reason for their visit is and what health symptoms or

problems they are experiencing.

• History of the Present Illness: The physician asks specific

questions to obtain detailed information about the patient’s current

illness or symptoms. This includes questions about duration, severity,

triggering factors, associated symptoms, and any previous treatment

undertaken.

• Medical History: The physician inquires about any previous

diseases or medical conditions the patient has experienced, as well as

any surgical procedures, hospitalizations, or known allergies.

• Family History: The physician asks about the medical history

of the patient’s close relatives, as some diseases may have a hereditary

component.

• Social History: The physician collects information about the

patient’s lifestyle, including dietary habits, physical activity, tobacco,

alcohol, or drug use, and any other factor relevant to health.

• Psychosocial History: The physician explores psychological

and social aspects that may influence the patient’s health, such as

stress, sleep quality, personal relationships, and work environment.

• Review of Systems: The physician conducts a detailed review

of the body’s different systems, asking specific questions to

identify any symptoms or problems (Figure 1).

The aim of following these steps in medical anamnesis is to obtain a complete picture of the patient’s medical situation, identify potential risk factors, establish a differential diagnosis, and plan an appropriate treatment. Anamnesis is, therefore, a fundamental part of the clinical evaluation and helps establish a solid doctor-patient relationship, based on trust and mutual understanding [16-18].

Medical Narratives

It is a reality that patient care assistance through digital platforms is increasingly being automated or technified [19,20]. This service provides an easy way for patients to make written contact with health professionals, considered beneficial for some patients and issues, but less suitable for more complex cases [21]. However, since the origins of medicine and patient treatment, medical narratives have been key both in the doctor-patient relationship and in the effective development of anamnesis [17,22-33]. Beyond the technical and scientific aspects of medicine, understanding the patient’s experience and perspective is crucial for providing compassionate and effective care. It is important to analyze how patients introduce information they consider important during medical consultations [34-38]. Therefore, the discursive strategies used by patients to present relevant information to their doctors have also been studied, often in the context of time constraints and the power dynamics inherent in the doctor-patient relationship [39]. The ethics of medical narrative is equally a relevant topic to consider [40]. Launer introduces the concept of Narrative- Based Medicine as an approach to improving mental health care in general practice. He argues that in the context of mental health, patients’ personal stories and the interpretation of their experiences are as important as clinical data and symptoms for understanding and effectively treating their conditions. Narrative-based medicine proposes that doctors adopt a more holistic and patient-centered approach, actively listening to and valuing patients’ narratives about their health and well-being. As Launer suggests, and this is what we want to highlight, this approach can offer a deeper understanding of mental health issues, revealing not only symptoms but also the social, emotional, and psychological context in which these symptoms occur [41].

Existing Methodologies in Older Adult Education

Various pedagogical methodologies have been applied in the education of older adults, including competency-based learning, service learning, and experiential education, among others [42-48]. These methodologies focus on the active participation of the student, the contextualization of learning in real situations, and the valuation of previous experiences [49-52]. However, they often lack a comprehensive approach that specifically considers the emotional and social characteristics of older adults, crucial aspects for their development and well-being as we have been demonstrating in our research on the subject [53-55].

Established Postulates

The postulates of older adult education emphasize the importance of a personalized approach, recognizing and valuing life trajectories, diversity of interests, and individual capacities. Gerontological pedagogy suggests the need to adapt educational strategies to promote meaningful and relevant learning that contributes to the personal and social enrichment of this age group [44,56-59]. The inclusion of emotional well-being as an essential component in the educational process is an emerging postulate, recognizing that emotional state significantly influences learning ability and motivation towards lifelong learning for older adults [60], as well as self-esteem [61-63]. Efforts are even being made to improve the emotional concept of aging among younger people through gerontological education [64]. The proposal for educational anamnesis is based on the integration of these concepts and methodologies, proposing a holistic approach that encompasses not only the cognitive and academic aspects but also the emotional and social aspects of older adult students. The implementation of this methodology seeks to establish an ongoing dialogue between students and educators, allowing for constant adaptation of pedagogical strategies to effectively respond to the needs and expectations of this group, promoting their overall well-being and empowerment in the educational process [65-73].

General and Specific Objectives

General Objective: To develop and implement the methodology

of educational anamnesis in lifelong learning for older adults, aiming

to personalize teaching, optimize emotional well-being, and enhance

effective learning for this group, while providing vital information to

professionals in comprehensive care for older adults.

Specific Objectives:

• Design a Comprehensive Educational Anamnesis Methodology:

Create a set of tools and processes based on anamnesis to collect

detailed information about the educational history, experiences,

emotions, and well-being of older adult students. This will include the

development of structured interviews, questionnaires, and other assessment

instruments tailored to the specific needs of this group.

• Establish an Interdisciplinary Theoretical Framework:

Ground educational anamnesis on a solid theoretical foundation integrating

knowledge from pedagogy, psychology of aging, and educational

gerontology, promoting collaboration among different disciplines

for more comprehensive care of older adults.

• Implement Case Studies and Collect Empirical Evidence:

Conduct practical research and case studies to assess the effectiveness

of educational anamnesis in improving the well-being and learning

of older adults. Collect and analyze quantitative and qualitative

data to adjust and refine the methodology.

• Compare Educational Anamnesis with Other Pedagogical

Models: Perform a comparative analysis between educational anamnesis

and other approaches to older adult education, identifying advantages,

challenges, and opportunities for integration to enrich the

educational offerings for this population segment.

• Develop Guidelines for Implementation and Evaluation:

Formulate clear guidelines for the implementation of educational

anamnesis, including the training of involved professionals and the

adaptation of spaces and educational resources. Define success indicators

and evaluation methods to measure the impact of the approach

on the well-being and learning of students.

• Promote Continuous Training and Professional Development:

Establish ongoing training programs for educators, psychologists,

social workers, and other professionals involved in the education

and care of older adults, ensuring they are equipped with the

necessary skills and knowledge to effectively implement educational

anamnesis.

• Encourage Active Participation and Student Empowerment:

Design strategies that promote the active participation of older adults

in their educational process, recognizing and valuing their previous

experiences, and encouraging their empowerment and autonomy in

learning.

• Create a corpus of scientific and empirical information that

can be exported to professionals in comprehensive care for older

adults, as many of them are involved in training processes like the

ones we propose.

• These specific objectives will guide the development and

implementation of educational anamnesis as an innovative and effective

tool in lifelong learning for older adults, significantly contributing

to their emotional well-being and academic success.

A specific methodology for educational anamnesis will be developed, starting with detailed interviews and questionnaires that allow for the collection of information on educational history, previous experiences, motivations, emotions, and overall well-being of the older adult student. This process will include identifying learning needs and preferences, as well as assessing their socio-emotional context. Indeed, an exploratory study will be carried out using surveys as a data collection instrument. Various questionnaires covering aspects related to educational history, past experiences, learning styles, current perceptions of cognition, satisfaction, emotions, and well-being of older adult students will be implemented. The sample will consist of older adult students from the Permanent University for Adults in Alicante (Spain) as a pilot test, to extend the research to the rest of the UPUA students, as well as to other similar training centers. Demographic data will be collected, and validated scales will be used to measure each of the interest variables. Data will be analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistical analysis, as well as qualitative analysis techniques to identify patterns and possible parallels between the methodology of medical anamnesis and educational assessment.

Therefore, an educational anamnesis methodology can be designed that includes the following steps:

a) Student Identification: Collect basic information about the

older adult student, such as name, age, gender, and study program,

among other relevant demographic data.

b) Reason for Consultation: Ask the older adult student what

the main reason for their participation in educational anamnesis is

and which aspects of their academic and personal experience they

would like to explore.

c) Cognition: Inquire about the older adult student’s learning

process, asking about their study strategies, critical thinking skills,

understanding of academic content, and any specific difficulties they

may be facing.

d) Satisfaction: Explore the level of satisfaction of the older

adult student with their educational experience, asking about the

quality of teaching, the support received, infrastructure and available

resources, and any other aspect that may influence their overall satisfaction.

e) Motivations: Investigate the motivations of the older adult

student for studying and being in those training cycles, asking about

their learning goals, personal interests, expectations, and any factor

that influences their motivation to learn.

f) Emotions: Explore the emotions of the older adult student

about their educational experience, asking about the level of stress,

anxiety, emotional satisfaction, and any other emotional aspect that

may be affecting their well-being.

g) Well-being: Inquire about the overall well-being of the older

adult student, asking about their balance between study and other

areas of their life, their level of social support, their quality of life, and

any factor that may influence their overall well-being (Figure 2).

Implementation of Case Studies and Collection of Empirical Evidence

Case studies will be implemented, and empirical evidence will be collected to demonstrate the effectiveness of educational anamnesis in enhancing the well-being and learning of older adults. These studies will focus on the practical application of the methodology and the evaluation of its outcomes, allowing for continuous adjustments and improvements to the approach. Data collection will be conducted using validated tools to ensure the reliability and validity of the obtained information. Among these are the Ryff Scales of Well-being and Mood [74-87], as well as the Positive and Negative Affect Scale [88]. To these surveys, already used by us with both university students [89] and older adult students [54], we now add a proposed survey for older adult students that covers aspects related to educational history and past experiences, as well as aspects related to emotions, motivation, and well-being. It includes open-ended questions and Likert scale questions: - Open-ended questions:

a) What was your main motivation for starting the educational

process?

b) What difficulties or challenges have you faced in your educational

journey so far?

c) What have been your most significant academic achievements

during your adult older educational experience?

d) Have you had any relevant educational or formative experience

outside the current educational setting (for example, themed

seminars, Erasmus, research projects, etc.)? If so, briefly describe it.

e) Which aspects of your older adult educational history do

you consider have influenced your personal and academic development?

f) How do you feel emotionally about your older adult educational

experience? Please describe your emotions and any factors that

may influence them.

g) What strategies do you use to manage stress and maintain

your emotional well-being during your time in older adult education?

- Likert scale questions (from 1 to 5, where 1 is “Strongly Disagree”

and 5 is “Strongly Agree”):

a) The education I received in earlier stages adequately prepared

me for older adult education.

b) I have had access to sufficient resources and support during

my time in older adult education.

c) Previous educational experiences have positively influenced

my academic performance as an older adult.

d) I am satisfied with my educational journey as an older adult

so far.

e) I consider the skills and knowledge acquired in earlier stages

to have been useful in my older adult educational life.

f) My emotional well-being has improved since I entered older

adult education.

g) I feel supported by my peers and teachers in my older adult

educational experience.

h) I am confident in my academic abilities and capacities.

i) I feel motivated and committed to my older adult education.

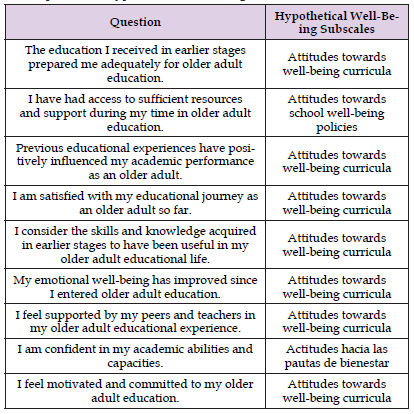

Therefore, we have developed a list of items for this new survey, which will undergo content validity analysis, leading to a second stage which will be an exploratory factor analysis of those items. To assess construct validity, we will rely on a proven methodology [90-92]. For this last survey, as was done with the previous ones, approval will be requested from the ethics committee of the International University of La Rioja (Spain). Regarding the study of well-being, the conceptualization of attitude has been emphasized [93-101], primarily through the ABC model of attitude [96,97,102]. This model posits that attitude consists of three distinct elements [103]. The affective element involves the emotions or feelings a person experiences towards a specific attitude object (for example, it could be said, “I feel anxious about the thought of speaking in public”). The behavioral aspect refers to the manifest actions or responses of a person towards an attitude object (such as, “I will opt to send emails instead of making phone calls whenever possible”). Lastly, the cognitive component encompasses the beliefs or knowledge a person has about an attitude object (for example, “I am convinced that written communication minimizes misunderstandings”). This model highlights the interrelationship between an individual’s feelings, actions, and beliefs toward various stimuli or situations, providing a comprehensive framework for understanding the complexity of human attitudes [104,105]. Therefore, based on the above, the items of the new survey will be linked to the three components of attitude, as discussed earlier by [97]: 1 = ‘Cognitive’; 2 = ‘Affective’; 3 = ‘Behavioral’, to perform the appropriate statistical analyses afterward (Table 1 & Figure 3). 2024. “Proposed Relationship of Attitudes with the ABC Model,” created by Pablo Rosser using diagrams. helpful.

Table 1: Questions on educational history, well-being, and their relationship with the ABC Model of attitude.

Dev, accessed February 12, 2024. Indeed, recent developments in the use of confirmatory methodologies within the social sciences spectrum have identified two inherent vulnerabilities in the model in research where attitudes have been defined as three-dimensional entities. Primarily, scrutiny of its internal composition has identified high interrelations among the three suggested components, complicating the assertion of their validity as distinct entities [106,107]. Additionally, research dedicated to elucidating attitude modification and the anticipation of behavior patterns has evidenced a tenuous connection between attitudinal dispositions and subsequent actions [93,107,108]. Bagozzi and Burnkrant [109] thus advocate for the adoption of a bi-dimensional approach in attitude modeling, integrating affective and cognitive components. This theoretical proposal suggests that the interactive dynamic between these two dimensions motivates the individual to develop a series of behavioral intentions, which ultimately guide their actions regarding the attitude object. This model suggests a structure in which three first-order latent factors converge to constitute a two-level system: one of the first order, linked to the affective component, and another of the second order, related to the cognitive component. The latter encompasses first-order factors, such as perceived utility, importance, and conservative beliefs [92]. Similarly, for the conduct of new quantitative analyses, items from this survey will be related to the aspect of well-being promotion (the ‘Attitudes towards Well-being Promotion’ scale or ATWP), in four hypothetical subscales:

(1) Attitudes towards the task of well-being promotion;

(2) Attitudes towards school well-being policies;

(3) Attitudes towards well-being curricula, and

(4) Attitudes towards well-being guidelines [90,110] (Table 2).

Table 2: Questions on educational history, well-being, and their relationship with the hypothetical well-being subscales.

Comparison with Other Educational Models

A systematic comparison between educational anamnesis and other models of education for older adults will be conducted. This comparison will be based on criteria such as efficacy, inclusion, emotional well-being, and adaptability. The goal will be to highlight the unique advantages of educational anamnesis, as well as to identify areas for improvement and opportunities for integration with other pedagogical approaches.

Guidelines for Implementation and Evaluation

For the implementation of educational anamnesis, clear guidelines must be established, which will include the training of professionals, the implementation of the data collection tools mentioned above, and the creation of learning spaces adapted to the needs of older adults. Specific success indicators will be defined, such as improvements in emotional well-being, satisfaction with the educational process, academic performance, and active participation in the educational community. The proposed evaluation methods will cover both quantitative and qualitative assessments, including satisfaction surveys, academic performance analysis, in-depth interviews, and focus groups. These methods will allow a comprehensive understanding of the impact of educational anamnesis and facilitate the identification of best practices and areas for improvement.

Expected Results

It is expected to find similarities and parallels between the methodology of medical anamnesis and the evaluation of educational history, learning styles, cognition, satisfaction, emotions, and well-being in older adult students. This could imply that, just like in medical anamnesis, understanding the educational history and past experiences of older adult students is crucial for understanding their academic development and social and psychological well-being. The results could highlight the importance of considering the educational context in the evaluation and design of student support strategies, as well as guidance for treatment in the comprehensive care of those by the various professionals who deal with them.

The adoption of anamnesis in medical contexts and its adaptability to educational settings for working with older adults has generated a body of experiences and learnings that deserve detailed discussion.

New Methodologies and the Digital Divide among Older Adults

Considering that several of the training courses for older adults we offer are online, precisely to promote that state of well-being and make it compatible with comprehensive care, we are particularly interested in addressing the disparity known as the Digital Divide. In this regard, we have advanced some conclusions in another study [55], and qualitative studies have been conducted exploring the challenges that information and communication technologies (ICT) have brought to adult education [2].

Well-Being and Comprehensive Care

Considering that, in its broadest sense, well-being can be conceptualized as a feeling of satisfaction with one’s mental, emotional, and physical state [90], the relevance of the eudaimonic perspective, characterized by a non-prescriptive approach to well-being that highlights the subjective dimension inherent to related experiences [111]. has been emphasized. Eudaimonia posits the axiom that “well-being constitutes a dynamic social construction, whose definition is subject to continuous contextual reconfiguration” [88]. Adopting this perspective implies recognizing a significant level of autonomy and diversity in experiences. Moreover, the pertinence of the eudaimonic tradition for conceptualizing subjective well-being within an educational framework has been underscored [112]. Regarding well-being and quality of life in more vulnerable sectors, and from a perspective of comprehensive or community care, community psychosocial interventions among people living with HIV/AIDS worldwide have been analyzed [113]. The 28 studies covered a wide range of intervention strategies, including coping skills, treatment, and cure, cultural activities, community participation, education on knowledge, counseling and voluntary testing, peer group support, three-tier service provision, group intervention targeted at children, adult mentoring, and support group interventions. Regardless of the study designs, all studies reported positive intervention effects, ranging from a reduction in HIV/AIDS stigma, loneliness, marginalization, distress, depression, anger, and anxiety to an increase in self-esteem, self-efficacy, coping skills, and quality of life.

Another interesting study focuses on women with breast cancer, highlighting the importance of assessing patient-based outcomes, such as quality of life, which is relevant for older adult education when considering their emotional well-being and quality of life [114]. In this case, adult women (over 18 years old) diagnosed with breast cancer who are receiving or have received treatment for breast cancer in the last ten years (i.e., surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and/ or hormonal therapy) were studied. Studies that focused on qualitative data, including, among others, designs such as phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, action research, and feminist research. It is equally important to underline that, as has been studied, there is good receptivity on the part of trainers to acquire the necessary protagonist in providing care in aspects related to well-being [94,95,99].

Experiences in the Medical Field

In the medical field, anamnesis, as we have discussed in the introduction, has proven to be an indispensable tool for the personalized diagnosis and treatment of older adults. The practice of collecting detailed medical histories allows health professionals to identify patterns, prevent complications, and tailor treatments to the specific conditions of each patient. For older adults, this practice is even more relevant due to the need for a comprehensive geriatric approach that considers physical, cognitive, and emotional aspects. Shafer & Fish advocate for the incorporation of personal narratives and patient history into training, for example, in anesthesiology. The authors argue that, beyond the technical and scientific aspects of medicine, understanding the patient’s experience and perspective is crucial for providing compassionate and effective care. Shafer & Fish discuss how modern medicine, with its emphasis on technology and diagnosis, often overlooks the importance of listening to and valuing patients’ personal stories. They argue that these narratives can offer significant insights into patients’ concerns, fears, and expectations regarding anesthetic and surgical procedures [34]. In this sense, integrating the patient’s narrative into professional education not only improves the doctor-patient relationship but also can contribute to better clinical outcomes. By better understanding the person behind the patient, care plans can be personalized, effectively addressing patient concerns and improving patient satisfaction with the medical care process. Practical methods for incorporating the patient’s narrative into anesthesiology training are proposed, including case discussion, written reflection, and fostering empathetic communication skills [34]. Similarly, how narrative-based practice can enhance the doctor-patient relationship, foster empathy and understanding, and facilitate more accurate diagnoses and personalized treatment plans has been highlighted. Launer advocates for integrating narrative skills training into medical education, arguing that such skills are essential for effective medical practice, especially in the field of mental health [41]. Moreover, Launer discusses the challenges of implementing Narrative- Based Medicine in general practice, including the need for more time for consultations and the development of active listening and reflection skills by doctors. Despite these challenges, it is concluded that the narrative approach has the potential to transform mental health care, offering more compassionate, comprehensive, and effective care [41]. Another study uses a discourse analysis approach to investigate interactions in medical consultations, identifying how patients signal the importance of what they are about to say and how they manage the presentation of delicate or potentially embarrassing information [39].

It is argued that, despite structural and social barriers, patients find creative ways to ensure their concerns are heard and considered by their doctors. This work highlights the importance of effective communication in the medical field and suggests that a greater understanding of patient communication techniques can help medical professionals improve the quality of patient care. By paying attention to patients’ verbal and non-verbal cues, doctors can foster a more collaborative and empathetic environment that benefits both patients and healthcare providers. The medical experience has underscored the importance of including questions related to quality of life, social support networks, personal autonomy, and psychosocial aspects in the anamnesis, which are crucial for the overall well-being of older adults. This holistic approach has significantly improved the doctor-patient relationship, fostering more empathetic dialogue and greater satisfaction with the received care [39]. Anamnesis is considered so important that a significant improvement in student’s ability to take medical histories in practice compared to the exclusive use of a virtual patient simulation program has been demonstrated [115].

Experiences in the Educational Field

In the educational field, adapting anamnesis to deeply understand older adult students is a less widespread but equally promising practice. Preliminary experiences indicate that by applying an educational anamnesis methodology, teaching programs can be better adapted to the needs, interests, and capabilities of older adults, promoting more meaningful and relevant learning. It has been argued that positive perceptions of health and well-being education are among the most important factors in terms of achieving successful comprehensive education [90]. On the other hand, conducting Student Experience Surveys, which assess satisfaction and the overall experience of older adult students about their education and include questions about the quality of teaching, the support received infrastructure, and available resources, among other relevant aspects, are of vital importance. Thus, the implications of using student experience surveys to improve the quality of teaching and learning within undergraduate nursing programs in Australia have been investigated. In this sense, the limitations of relying exclusively on student satisfaction surveys for course development and teacher evaluations are emphasized [116]. In the same vein, student experience surveys have become increasingly popular for investigating various aspects of processes and outcomes in higher education, such as measuring students’ perceptions of the learning environment and identifying aspects that could be improved [117].

An overview and summary of a Mature Student Experience Survey conducted between 2010 and 2013 have been published by [118]. It highlights how student experience surveys are used to assess and improve the quality of education in different contexts and disciplines. The Educational History Survey collects detailed information about students’ educational history, including their academic trajectory, previous experiences in the education system, academic achievements, and challenges encountered, among other relevant aspects. Given the importance of educational history, the active development of digital educational infrastructure has been proposed, allowing educational institutions to collect and store large amounts of data related to the learning process. Thus, the digitalization of the student’s educational history is proposed as a key component of the student’s digital profile, highlighting the importance of describing, structuring, and combining various data about the student into a single digital profile to apply an integrated approach to data-based educational process management [119]. There are also Motivation and Educational Goals Surveys, which assess students’ motivations and educational goals. They include questions about the reasons for studying, academic goals, personal interests, and any other factor that may influence the motivation to learn. From this, a study examines the relationship between educational values and goals, student motivation, and study processes, and how values attached to educational goals predict students’ motivation and study processes [120].

A study investigated university students’ achievement goals for using Open Educational Resources (OER) from the perspective of expectancy- value theory [121]. Lastly, we have the Student Well-being Scale. This scale assesses students’ overall well-being, including their balance between study and other areas of life, their emotional satisfaction, their stress level, and any other aspect related to well-being. As we have mentioned in another section, the study analyzed a test instrument to quantify educators’ attitudes toward the promotion of student well-being in post-primary Irish schools. It was conducted in three stages: content validity with experts and educators, exploratory factor analysis, and confirmatory factor analysis, resulting in a viable 10-item, two-factor model called ‘Attitudes Towards Well-being Promotion’ (ATWP [90]. On the other hand, the initial development and validation of a teacher-reported scale to assess student well-being have been studied. The scale seeks to provide a reliable tool for educators to report on their students’ well-being [122]. Along the same line, a study investigated the effect of an elective visual arts course on medical students’ well-being, finding significant improvements in mindfulness, self-awareness, and stress levels [123].

Linked to the pandemic but with profound implications for our project, a study examines whether a well-being module for final-year undergraduate students improved well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants showed a significant increase in well-being, compared to population norms, suggesting that fostering a connection with oneself, others, and nature has beneficial impacts on well-being [124]. On a different but equally interesting note, a study analyzes the emotions and opinions expressed by students in different types of speeches and universities, correlating them with survey-based data on student satisfaction, happiness, and stress. The findings suggest that social media can be a useful tool for measuring student well-being [125]. Therefore, the discussion about experiences in both fields suggests that anamnesis, whether medical or educational, represents a valuable approach to working with older adults. Integrating this practice into older adult education not only enriches the learning process but also aligns educational offerings with the principles of gerontology, which advocates for a comprehensive and respectful approach to aging.

The implementation of educational anamnesis in older adult education is anticipated as a significant advance toward more personalized and comprehensive pedagogy. Through a detailed methodology, solid theoretical foundation, interdisciplinary collaboration, and a systematic focus on evaluation and continuous improvement, it is expected not only to enrich the educational experience of older adults but also to contribute to the academic and scientific field with new knowledge and innovative practices. This approach represents a commitment to improving the well-being and quality of life of older adults, ensuring that their educational journey is both enriching and empowering. All this will undoubtedly impact comprehensive care based on the valuable information generated by educational anamnesis.

The Application of Anamnesis in Education and Pedagogy

Although anamnesis is a tool effectively used in medicine to collect information about a patient’s medical history, we propose that its methodology of analysis can be similarly applied in Education and Pedagogy, and more specifically to older adults. In this context, educational anamnesis refers to the collection of information about the educational history of an older adult student, including their previous experiences, skills, interests, strengths, and challenges. The goal is to gain a more complete understanding of the student to better tailor teaching methods and design effective educational strategies that improve their social and psychological well-being. The methodology of educational anamnesis involves conducting a series of questions and interviews with the students, tutors, and other professionals involved in their education. These questions may cover topics such as academic performance, learning preferences, extracurricular interests, learning difficulties, motivation, and educational goals. Once this information is collected, it can be used to develop personalized teaching plans, adapt the curriculum, identify potential areas for improvement, and set realistic educational goals. It can also help educators better understand the needs and strengths of each student, thus fostering a more inclusive and effective learning environment (Figure 4).

The Application of Anamnesis in Education and Pedagogy

Although anamnesis is a tool effectively used in medicine to collect information about a patient’s medical history, we propose that its methodology of analysis can be similarly applied in Education and Pedagogy, more specifically to older adults. In this context, educational anamnesis refers to the collection of information about the educational history of an older adult student, including their previous experiences, skills, interests, strengths, and challenges. The goal is to gain a more complete understanding of the student to better tailor teaching methods and design effective educational strategies that enhance their social and psychological well-being. The methodology of educational anamnesis involves conducting a series of questions and interviews with the students, tutors, and other professionals involved in their education. These questions may cover topics such as academic performance, learning preferences, extracurricular interests, learning difficulties, motivation, and educational goals. Once this information is collected, it can be used to develop personalized teaching plans, adapt the curriculum, identify potential areas for improvement, and establish realistic educational goals. It can also help educators better understand the needs and strengths of each student, thereby fostering a more inclusive and effective learning environment. 2024. “Educational Anamnesis Methodology,” created by Pablo Rosser using diagrams.helpful.dev, accessed February 12, 2024.

Enhancing Knowledge of Students’ Emotions and Well-being

Understanding students’ emotions and well-being should also be a fundamental aspect of educational anamnesis. When collecting information about the educational history of an older adult student, it is equally important to consider their emotional state and overall well-being. Emotions play a crucial role in the learning process. Older adult students who feel secure, motivated, and emotionally balanced tend to achieve optimal academic performance. Conversely, those experiencing high levels of stress, anxiety, or emotional issues may struggle to concentrate and learn effectively, which could also affect their physical health and emotional state.

Therefore, in the context of educational anamnesis, specific questions about students’ emotions and well-being can be included. These questions may address issues such as stress levels, self-esteem, emotional management, relationships with peers and teachers, and any other factors that may affect their emotional well-being. By gaining information about the emotions and well-being of older adult students, educators can identify potential emotional challenges and design appropriate support strategies. This may include the implementation of stress management techniques, promoting a safe and welcoming learning environment, and collaborating with mental health professionals when necessary. Furthermore, understanding students’ emotions and well-being can help educators establish stronger and more empathetic relationships with older adult students. By better understanding their emotional needs, educators can provide appropriate support and foster an environment of trust and mutual respect.

The Influence of Educational Anamnesis Outcomes on Care for Older Adult Patients

On the other hand, it’s evident that understanding the emotions and well-being of older adult students attending face-to-face or online training, their stress levels, concerns, etc., are essential components of educational anamnesis and can have a very positive impact on the comprehensive care of this population segment. By collecting information on these aspects, not only educators but also doctors, nurses, psychologists, and other comprehensive care professionals can adapt their therapeutic approaches and treatments and provide the necessary support to promote a healthier state of well-being in its broadest sense.

A Proposed Methodology for Educational Anamnesis

The methodology of educational anamnesis and the focus on understanding students’ emotions and well-being can be used in various educational contexts, fundamentally, or with more interest in older adult students due to their special characteristics and greater vulnerability to mood states, with the clear positive or negative repercussions this may have on their well-being. Just as in medicine, it’s necessary to recognize the importance of understanding the educational and emotional history of older adult students to improve their learning experience and, above all, positively impact their level of well-being. Looking to the future, a scenario is envisioned where educational anamnesis becomes a standard practice within education programs for older adults. This will require specific training for educators, as well as a shift in the organizational culture of educational institutions, which must value and promote the comprehensive well-being of their students. The accumulated experience in the medical field can serve as a guide and motivation for this process, highlighting the effectiveness of a personalized and holistic approach in working with older adults.

There is no financial interest or conflict of interest.