Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Pablo Rosser1* and Seila Soler2

Received: January 18, 2024; Published: January 31, 2024

*Corresponding author: Pablo Rosser, Universidad Internacional de La Rioja, Logroño, España, Avenida de la Paz, 137, 26006 Logroño, La Rioja, España - Facultad de Educación, Spain

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2024.54.008602

This pilot study addresses the relationship between wellbeing and emotions in older adult students at the Permanent University of Adults in Alicante (Spain). The overarching objective is to analyze how education impacts their wellbeing and personal satisfaction or how it can be adapted to enhance such wellbeing. The aim is to characterize the wellbeing profile of these adults through the analysis of central tendency and dispersion of survey responses. The hypotheses are centered on the existence of significant differences in wellbeing among demographic groups (age and gender) and the grouping of items into different dimensions of wellbeing (emotional and social). The results indicate notable variations in wellbeing based on age and gender, thereby validating the hypothesis of demographic differences. Furthermore, multiple dimensions of wellbeing were identified through item grouping. These findings suggest the necessity to tailor education to focus on specific aspects of wellbeing, such as the development of communicative skills and the formation of strong relationships, which could enhance the quality of life and satisfaction of older adults. This study provides a valuable foundation for future research and pedagogical practices in the education of older adults, emphasizing the importance of an education adapted to their specific needs.

Keywords: Wellbeing; Emotions; Older Adults; Lifelong Learning; Statistical Analysis; Mental Health

In the context of a society undergoing ageing, the emotional and psychological wellbeing of older adults emerges as a subject of increasing social and academic significance. The Permanent University of Adults in Alicante (Spain), as an institution dedicated to the education of this demographic group, is positioned at the epicentre of this relevant discourse [1,2]. This pilot study focuses on unraveling how educational experiences at this university impact, or could potentially impact, the wellbeing and emotions of its older students. The relevance of this topic extends beyond the academic realm, reaching into considerations of social policy and public health, as the wellbeing of older adults has direct implications for their quality of life and broader social dynamics. In this regard, the importance of developing and implementing targeted community interventions to reduce social isolation among older adults and enhance their quality of life has been underscored. [3,4]. Some studies also examine how digital social interactions affect the daily wellbeing of older adults, highlighting the significance of digital communication technologies in their social lives [5]. Other research explores differences in measuring difficulties among older adults in relation to sociodemographic characteristics [6]. In the contemporary context of active ageing, an emerging paradigm underscores the importance of continuous opportunities for learning and personal growth [7,8].

This paradigm highlights the significance of plasticity, individual initiative, and the promotion of wellbeing—key elements in the conception and implementation of educational programs for the older population, particularly within university settings and specific programs for seniors [9]. Various motivations drive the pursuit of educational opportunities by older adults. According to recent studies, engagement in educational activities during this life stage not only enhances cognition and psychological wellbeing but also serves as an effective means to combat social isolation [10], thus contributing to active and healthy ageing [11]. Several research endeavors have addressed topics such as the adaptation of older adults to digital technologies, the effectiveness of in-person and online educational programs in terms of learning, and their impact on psychological wellbeing and the quality of life of this population [12-15]. These studies underscore the relevance of adapting educational methods to the needs and capacities of older adults, considering both digital and in-person environments, and evaluating their influence on various aspects of seniors’ lives, from mental health to social integration [16-19]. From an academic standpoint, this study addresses a gap in existing research by specifically linking the educational environment with the emotional and psychological wellbeing of older adults [20]. While prior literature has extensively examined the benefits of lifelong learning during this life stage, there is a need to delve into how instructional classes can be adapted to maximize these benefits.

This approach is particularly relevant in an era where education for older adults is not only considered a tool for personal enrichment but also as a means to promote active and healthy ageing. This study builds upon a prior analysis [1], and a methodology proposed by us [2], drawing from the student body that participated in an online course offered by the Permanent University of Alicante (UPUA), taught by one of the authors of this research. The current study establishes a framework for exploring these dynamics with the aim of identifying key factors influencing the wellbeing of older adults in an educational context. In doing so, it is expected to contribute to the design of educational programs that are not only informative and enriching but also mindful and responsive to the emotional and psychological needs of this population. The research, therefore, holds significance not only from an academic perspective but also has the potential to inform practices and policies in the field of older adult education, emphasizing the importance of a holistic approach that integrates educational, emotional, and social aspects.

General Objective

To assess and comprehend the relationship between the wellbeing and emotions of older adult students at the Permanent University of Adults in Alicante, aiming to identify key factors that help understand the extent to which instructional classes impact them. Additionally, to explore how these classes should be adapted to contribute to their quality of life and personal satisfaction.

Specific Objective

• Characterize the wellbeing profile of older adults through measures of central tendency and dispersion of responses from the wellbeing survey.

Hypotheses

• H1: There are significant differences in perceived levels of

wellbeing among different demographic groups (by age and

gender) in the studied population.

• H2: Survey items on wellbeing cluster into different factors

representing distinct dimensions of wellbeing (e.g., emotional

wellbeing, social wellbeing).

Study Design

The methodology for this pilot study is primarily descriptive and quantitative, based on surveys crafted using the Ryff Well-Being and Mood Scale and its adaptations [21-37]. The survey results are analyzed through descriptive and frequency analyses, presenting measures of central tendency and dispersion concerning age, gender, and various items on the Wellbeing scale. The analysis of these items will include response distribution, trends in responses, interpretation of results, relevance to psychological wellbeing, and recommendations for implementation in instructional classes based on these findings.

Participants

The target population for this research comprised older adults enrolled in online educational programs at UPUA. For this pilot test, 15 individuals from a course on the History of Spain through Poison taught by one of the authors of this research participated. Participation in the study was strictly voluntary, and participants collaborated altruistically and anonymously, without receiving external incentives. Additionally, implicit consent was obtained from participants, providing information on the study’s objectives, potential risks, contact details of the researchers and the responsible institution, as well as the benefits of participating in the study. This ensured participants’ autonomy and the protection of their personal data in accordance with current data protection legislation. No specific exclusion criteria were established, as the aim was to encourage the inclusion of a broad range of UPUA students to obtain a diverse and representative sample of the target population. This inclusive approach was essential to ensure the generalizability and relevance of the study’s findings.

Instruments

Regarding evaluation instruments, a single questionnaire was selected, which had been previously validated and used in educational research. This questionnaire is considered a reliable and valid instrument for assessing students based on the previously stated research objectives. The administration of the questionnaire, which constituted an essential part of the assessment, had an estimated duration of between 20 and 30 minutes and was conducted at the beginning of the instructional classes. Each item in the survey instrument was designed to relate to a specific dimension of the survey, and appropriate statistical analyses were employed to assess the relationships between these variables and other study variables. The selected instrument was, as previously mentioned, the Ryff Psychological Well-Being Assessment Questionnaire [21], widely recognized and validated in scientific literature, with pertinent adaptations [31,32,34]. For the analysis of wellbeing and mood variables, the responses provided in the Ryff questionnaire were used. Each item in the questionnaire was associated with a specific dimension of wellbeing or mood. Responses were analyzed using 6-point Likert scales, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The analysis included the comparison of wellbeing and mood levels by gender, the correlation between wellbeing levels and participants’ age, and the exploration of other variables of interest in the study.

Data Analysis

A Descriptive Analysis will be implemented, involving the calculation of measures of central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion (standard deviation, range) for each item in the survey. This analysis is also useful for checking data quality, including identifying missing values and atypical responses.

The following are the results of the Descriptive Analysis, including measures of central tendency and dispersión.

Age

The majority of participants belong to the age group of 66-75 years, constituting over half of the sample (53.3%). The second-largest group is the 56-65 age group, comprising one-third of the participants (33.3%). The age groups of 46-55 years and 76-85 years are less represented, with only one participant in each, accounting for 6.7% of the sample for each group (Table 1). Therefore, the distribution of ages is not balanced. Most participants are in the 66-75 age group, which could influence the overall study results and limit the generalization of findings to other age groups. When analyzing item responses, it is crucial to consider this distribution. However, despite being a pilot study preceding a broader investigation with a more diverse student sample, it is essential to recognize an intrinsic characteristic of the profile of students at the Permanent University of Adults in Alicante (UPUA): notable heterogeneity in terms of ages. This age diversity is a crucial factor to consider in the planning and execution of the subsequent research.

Note: Own elaboration.

Gender

There is a higher proportion of women (60%) compared to men (40%) in the study sample. This difference suggests a leaning towards a greater female representation (Table 2). The higher proportion of women could influence the study results, especially if there are gender differences in responses to the items. Therefore, when conducting analyses comparing men and women, it is essential to consider this difference in proportion. Any findings should acknowledge that the women’s group is larger than the men’s group. Similarly, combining gender analysis with age categories may reveal relevant conclusions, especially if certain trends or patterns are associated with a specific gender within a particular age range.

Note: Own elaboration.

Item Analysis

Items on the Wellbeing scale with a higher mean (> 4.5) suggest a positive perception or agreement with the statements. This includes life satisfaction, self-assurance, and being active in pursuing projects. Items with a lower mean (< 3.0) indicate concern or disagreement. This includes feeling lonely, concern about how others evaluate their choices, and doubts about the direction of life. Variability (Standard Deviation) in responses is notable in several items, especially those related to loneliness, concern about others’ opinions, and satisfaction with life achievements.

Life Satisfaction and Loneliness: Participants tend to be content with their lives (Item 1, mean 4.4667) but also experience some degree of loneliness (Item 2, mean 3.0667). To analyze these data, we will first consider the responses to the statement in Item 1 (“When I look back on my life, I’m pleased with how things have turned out”), using the Likert scale, where 1 represents strongly disagree and 6 strongly agree (Table 3). A significant majority of respondents (80.0%, combining categories 5 and 6) exhibit a high level of satisfaction with the course of their lives. There is a range in satisfaction levels among respondents, although the majority leans towards satisfaction. These results suggest that most respondents feel content when looking back on their lives, indicating a positive perception of their experiences and achievements. However, the variability in responses indicates that while many feel satisfied, some have mixed or less positive feelings about how things have turned out in their lives. Feeling content with life’s trajectory is a crucial component of psychological well-being, reflecting a sense of accomplishment and fulfillment. A positive perception of one’s life journey is associated with increased self-acceptance and resilience. For those with lower levels of satisfaction, exploring strategies in education to enhance their life perception and find positive aspects in their experiences would be beneficial.

Note: Own elaboration.

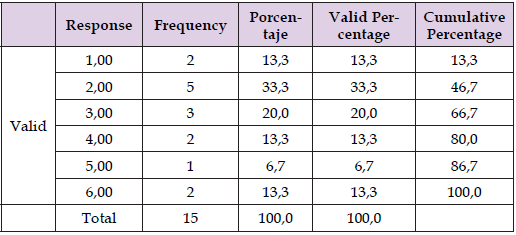

Similarly, in future research, it would be interesting to delve into the ‘Why’, exploring the reasons behind these positive perceptions: are they related to personal achievements, relationships, or a general attitude toward life?. Considering everything mentioned, promoting positive reflection, acknowledging achievements, and learning from past experiences can be useful in the instructional classes for those seeking to increase their life satisfaction. On the other hand, to analyze loneliness, we will consider the responses to the statement in Item 2 (“I often feel lonely because I have few close friends with whom to share my concerns”) (Table 4). The results reveal a diverse distribution regarding the experience of loneliness related to the number of close friends. A significant 33.3% of respondents (combining categories 5 and 6) show a notable agreement with feeling lonely due to having few close friends. The variability in responses may reflect different experiences and perceptions of loneliness, as well as differences in the quality and quantity of intimate relationships. Concerning the relevance to Psychological Well-being, having intimate and satisfying relationships is fundamental, and the lack of these can contribute to feelings of loneliness. Loneliness and the quality of social relationships are closely linked to mental health and overall quality of life. For those who feel more lonely, it may be beneficial in instructional classes to encourage the building and maintenance of intimate and meaningful friendships. Similarly, promoting participation in social activities, the development of communication skills, and the creation of supportive environments can be helpful for those experiencing loneliness.

Table 4: Item 2: I often feel lonely because I have few close friends with whom to share my concerns.

Note: Own elaboration.

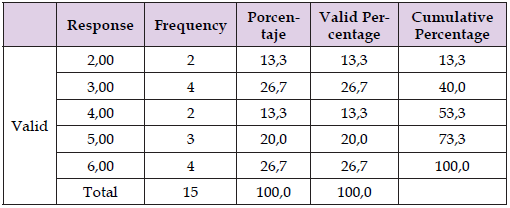

Expression of Opinions: The majority is not afraid to express their opinions (Item 3, mean 4.2), but there is concern about how others perceive their choices (Item 4, mean 2.3333). To analyze these data, we will first consider the responses to the statement in Item 3 (“I am not afraid to express my opinions, even when they are opposite to the opinions of most people”) (Table 5). A significant majority of respondents (60.0%, combining categories 5 and 6) demonstrate a high level of agreement with feeling comfortable expressing their opinions, even when contrary to the majority. However, 40.0% of respondents (combining categories 2, 3, and 4) exhibit lower confidence or moderate confidence in expressing opinions contrary to the majority. These results suggest that the majority of respondents have an independent and confident attitude towards expressing their opinions, even in contexts where these opinions differ from the majority. The variability in responses may reflect differences in personality, self-confidence, and past experiences in situations of dissent.

Table 5: Item 3: I am not afraid to express my opinions, even when they are opposite to the opinions of most people.

Note: Own elaboration.

Understanding how people feel about expressing opinions can be relevant for group dynamics in social and professional contexts. Similarly, it would be useful to further investigate factors contributing to these attitudes, such as gender, age, or socioeconomic context, in future research. Regarding the relevance to Psychological Well-being, feeling free to express one’s opinions, even when contrary to the majority, is important as it promotes authenticity and self-expression.

On the other hand, the ability to hold and express personal opinions in oppositional contexts is linked to higher self-esteem and resilience. For those who feel less confident, it would be beneficial in instructional classes to encourage confidence and the ability to express personal opinions in contexts of dissent. Similarly, promoting the development of assertive communication skills and fostering an environment that supports diversity of opinions can be beneficial in strengthening confidence in self-expression. Next, we will analyze the responses to the statement in Item 4 (“I am concerned about how other people evaluate the choices I have made in my life”) (Table 6). A significant majority of respondents (60.0%, combining categories 1 and 2) are not concerned or are slightly concerned about how others evaluate their life choices, although 33.3% of respondents (category 3) hold a neutral or moderately concerned position regarding others’ opinions. Regarding the relevance to Psychological Well-being, being less excessively concerned about external evaluation is crucial, as it promotes autonomy and confidence in one’s decisions. A lower concern for others’ opinions is associated with increased self-efficacy and a sense of independence in decision-making. For those more affected by others’ opinions, it would be beneficial in instructional classes to work on strengthening autonomy and confidence in their own decisions. Promoting the development of self-esteem, self-confidence, and skills for managing social influence can also be beneficial for those feeling more concerned about external evaluation.

Note: Own elaboration.

Life Direction: There is a certain difficulty in directing life towards a satisfying path (item 5, mean 2.8), and doubts about what is sought to be achieved in life (item 29, mean 2.2667). To analyze these data, we will first examine the responses to the statement of item 5 (“I find it challenging to direct my life towards a path that satisfies me”) (Table 7). The distribution of responses shows a variety in the perception of respondents’ ability to direct their lives towards satisfaction. A significant 46.6% of respondents (summing categories 4 and 5) indicate some difficulty in directing their lives towards a satisfying path. These results suggest a division among respondents regarding their ability to self-direct their lives towards personal satisfaction. Therefore, the proportion of responses in the middle and upper range of the scale indicates that a significant portion of respondents faces challenges in managing their lives in a way that is personally satisfying. Regarding the relevance to Psychological Well-being, the ability to direct life towards a satisfying path is crucial, as it is linked to the sense of control and purpose in life. Feeling capable of directing life towards satisfaction is also related to higher self-efficacy and effective planning and decision-making skills. For those experiencing difficulties, it would be beneficial to explore strategies in training sessions to enhance self-direction and life satisfaction. Fostering the development of life planning, decision-making skills, and self-efficacy can be equally helpful in improving individuals’ capacity to steer their lives towards a more satisfying path.

Note: Own elaboration.

In the second instance, we will analyze the responses to the statement of item 29 (“I am not clear about what I am trying to achieve in life”) (Table 8). A majority of respondents (73.3%, combining categories 1 and 2) disagree with the idea that they lack clarity about what they are trying to achieve in life. Only 13.4% of respondents (combining categories 4 and 5) show some degree of agreement with the lack of clarity in their life goals. In terms of relevance to Psychological Well-being, having clarity about life goals is crucial, as it provides direction and a sense of purpose. Feeling clear about goals and aspirations is also associated with better life planning and a greater sense of self-efficacy. For those with less clarity, it would be helpful in training sessions to encourage self-exploration and the establishment of clear goals. Promoting the development of a clear life vision, along with planning and goal-setting, can also be beneficial for those seeking greater clarity in their aspirations.

Note: Own elaboration.

Personal and Social Relationships: Participants value their relationships and feel supported (items 14 and 32), but there is also a sense of having fewer friends compared to others (item 20). To analyze this data, we will first examine the responses to the statement of item 14 (“I feel that my friendships bring me many things”) (Table 9). A significant majority of the respondents (86.7%, summing up categories 4, 5, and 6) feel that their friendships bring them a lot, indicating a positive perception of the value of their friendships. Only a small percentage (6.7%, category 1) totally disagrees with their friendships bringing them a lot. Regarding the relevance to Psychological Well-being, maintaining friendships perceived as enriching is crucial. In this regard, feeling that friendships contribute a lot is associated with higher self-esteem and a solid social support network.

Note: Own elaboration.

For those who feel their friendships contribute less, it would be beneficial to encourage the development of healthier and more enriching friendships in training sessions. Promoting the building of strong and meaningful friendships and fostering communication and empathy skills can also be beneficial for improving the quality of social relationships. Next, we will analyze the responses to the statement of item 32 (“I know I can trust my friends, and they know they can trust me”) (Table 10). A significant majority of respondents (93.3%, summing categories 4, 5, and 6) indicates a high level of trust in their friends and feels that this trust is mutual.

Note: Own elaboration.

Only a small proportion (6.7%, category 1) strongly disagrees with having a relationship of mutual trust with their friends. In terms of relevance to Psychological Well-being, having friendships where trust prevails is crucial, as it provides a sense of security, support, and connection. Similarly, trust in friendships is associated with higher self-esteem and better social integration. For those indicating a lower level of trust, it would be beneficial to explore ways to strengthen trust in their relationships during training sessions. Promoting the building of strong and reliable friendships and fostering communication and empathy skills can also be beneficial for strengthening trust bonds. Thirdly, we will analyze responses to the statement of item 20 (“I feel that most people have more friends than I do”) (Table 11). A majority of respondents (60.0%, combining categories 1 and 2) disagree with the idea that other people have more friends than they do. Meanwhile, 26.7% of respondents (combining categories 5 and 6) agree or strongly agree with the perception that others have more friends. These results suggest a variety of perceptions among respondents regarding how they view their circles of friendship compared to others. The variability in responses may reflect different levels of satisfaction with social relationships and different perceptions of the quantity and quality of friendships. In terms of relevance to Psychological Well-being, having a positive perception of social relationships and being satisfied with the number of friendships is important. How a person perceives their social situation compared to others may be related to their self-esteem and sense of social integration. For those who feel that others have more friends, it could be useful to promote social integration and the development of interpersonal skills in training sessions. Encouraging participation in social activities and the development of interpersonal skills can be beneficial for those looking to expand their circles of friendship.

Note: Own elaboration.

Personal Development and Change: There is a strong sense of learning and personal development over time (items 37 and 38), although there is also resistance to making significant changes (item 34). To analyze these data, we will first consider the responses to the statement of item 37 (“I have a sense that over time I have developed a lot as a person”) (Table 12). All survey respondents (100%) demonstrate a high degree of agreement (categories 5 and 6) in having experienced significant personal development over time. The unanimity in responses indicates a generally positive attitude towards personal growth and self-improvement.

Note: Own elaboration.

Regarding the relevance to Psychological Well-being, the perception of having developed significantly as a person is crucial, as it reflects a sense of progress and personal fulfillment. A positive perception of personal development is associated with increased self-efficacy and life satisfaction. Given the high level of agreement, the focus in educational settings could be on maintaining and enhancing this sense of personal growth. Promoting strategies and opportunities for continuous personal development, such as education, challenging experiences, and personal reflection, can be beneficial in sustaining and enriching this perception. Next, we will analyze the responses to the statement of item 38 (“For me, life has been a continuous process of study, change, and growth”) (Table 13).

Note: Own elaboration.

A significant majority of respondents (93.3%, combining categories 5 and 6) express a strong affinity with the notion that life is a continuous process of study, change, and growth. Only a small proportion (6.7%, category 4) somewhat agrees, still indicating a positive inclination towards this perception. Regarding its relevance to Psychological Well-being, perceiving life as a continuous process of study, change, and growth is crucial as it fosters adaptability, resilience, and a sense of purpose. A positive perception of personal growth and development is associated with higher self-efficacy and life satisfaction. To sustain and reinforce this perception, it would be beneficial to continue promoting learning and personal development opportunities in training sessions. Encouraging self-exploration, continuous learning, and adaptability can be advantageous in strengthening this positive trend towards personal growth. Thirdly, we will analyze the responses to the statement of item 34 (“I do not want to try new ways of doing things; my life is fine as it is”) (Table 14). The results reveal a diverse distribution in attitudes towards change and the adoption of new ways of doing things. Some prefer to maintain the status quo, as evidenced by 46.7% of respondents (summing categories 4 and 5) expressing some degree of agreement with the preference to keep things as they are without seeking new ways of doing them. These results suggest a variety of perspectives among respondents regarding comfort with their current situation and openness to change.

Note: Own elaboration.

Regarding the relevance to Psychological Well-being, the ability to adapt and try new ways of doing things can be crucial for personal growth and resilience. Striking a balance between comfort with the status quo and openness to change is key to personal and professional well-being. For those showing resistance to change, it might be useful to explore the reasons behind this attitude and encourage, in training sessions, openness to new experiences. Promoting flexibility, adaptability, and the exploration of new ways of doing things can be beneficial, especially for those who tend to prefer the status quo. The implementation of active methodologies in training could be an interesting experience in this regard.

The results obtained in this pilot study reveal significant findings regarding the hypotheses and objectives outlined. The results confirm the hypothesis that there are significant differences in perceived well-being among various demographic groups of older adults, particularly in terms of age and gender. This aligns with the overall goal of assessing how training courses at the Permanent University for Older Adults in Alicante impact, or could impact, their well-being and personal satisfaction. Some authors have emphasized that learning in later stages positively impacts mental, emotional, physical health, and overall well-being [38]. Furthermore, a positive correlation has been demonstrated between learning and health in older adults, improving psychological aspects such as life satisfaction and well-being [39]. Similarly, lifelong learning has been associated with the reduction of cognitive decline in older adults, even with short participation in cognitively stimulating activities [40]. Several studies have shown that computer use increases social interaction, self-esteem, and enhances certain abilities [41-44]. When comparing our findings with previous studies, as we have just seen, there is alignment with existing literature suggesting a significant relationship between education and well-being in old age. However, this study adds a new dimension by specifically focusing on how training courses can be adapted to enhance this well-being, an area less explored in previous research.

Other studies on psychological or social well-being in older adults have been conducted, but from different perspectives and with objectives distinct from ours, albeit of great interest. For example, pragmatic, equitable, and cost-effective interventions to enhance the well-being of older residents in eldercare facilities have been addressed [45]. Another study explores the association between psychological and social well-being and the rate of decline in physical function over time in older adults [46]. Yet another examines the associations between social support from different types of relationships and psychological well-being, along with the mediating effects of satisfaction of basic psychological needs in these associations [47]. An attempt has even been made to determine the impact of specific social determinants of health on psychological health and well-being among older Black and Hispanic/Latino adults compared to White adults [48]. More focused on our educational context is research that evaluated the preliminary effects of a WeChat-based educational intervention on the social participation of older adults in China, finding significant improvements in social participation and self-worth [49]. Similarly, sociodemographic, cognitive, attitudinal, emotional, and environmental factors influencing the intention of older adults to use new digital technologies have been reviewed [50]. From a practical standpoint, the results of our pilot study underscore the importance of considering emotional and psychological well-being in the education of older adults.

This involves adapting training classes to address specific aspects of well-being, such as communication skills and relationship building, which can directly impact the quality of life of older adults. Regarding limitations, this pilot study faces constraints in terms of sample size and scope. The preliminary nature of the research suggests the need for caution when generalizing findings to a wider population. Additionally, while quantitative methodology provides concrete data, a more qualitative perspective could offer a deeper understanding of the individual experiences of older adults. This not only enriches the understanding of the impact of education on their well-being but also may reveal new areas for pedagogical adaptation. Conducting longitudinal studies could furnish valuable insights into the long-term effects of educational interventions on the well-being of older adults. Additionally, it would be advantageous to scrutinise how additional variables, such as the socio-economic and cultural environment, impact the relationship between education and well-being in this population.

In this article, the relationship between well-being and emotions in older adult students at the Permanent University of Adults in Alicante (Spain) was assessed and understood, aiming to identify key factors influencing how instructional classes impact, or could impact, their quality of life and personal satisfaction. Employing a quantitative and descriptive methodology based on Ryff’s Well-being Scale, the well-being profile of older adults was characterized. The results of this pilot study confirmed significant differences in perceived well-being levels among different demographic groups, specifically based on age and gender, thereby confirming hypothesis H1. Additionally, a clustering of items into different factors representing distinct dimensions of well-being, such as emotional and social well-being, was observed, validating hypothesis H2. These findings have significant pedagogical implications. It is recommended to adapt instructional classes to address specific well-being aspects. This includes designing activities that promote reflection on past experiences and recognition of personal achievements to enhance life satisfaction. Incorporating dynamics that stimulate the formation of friendships and the development of communication skills to combat loneliness is also advised [51]. It is crucial to create a classroom environment that supports diversity of opinions, fosters confidence in self-expression, and encourages personal autonomy. Furthermore, including content that helps students set clear goals and develop life planning and decision-making skills, addressing life direction, is advised.

To strengthen personal relationships, it is beneficial to encourage the development of strong and reliable relationships through activities that enhance communication and empathy. Regarding personal development and adaptability, offering opportunities that foster continuous learning, flexibility, and openness to new experiences, especially to address resistance to change, is proposed. The contribution of this study to the field of well-being and education for older adults is notable and multifaceted. Firstly, it provides a deeper understanding of the relationship between emotional well-being and the educational experiences of older adults. By specifically evaluating how instructional classes at the Permanent University of Adults in Alicante impact their well-being, the study offers empirical evidence to guide pedagogical practices towards a more holistic and individual-centered approach. Secondly, by using Ryff’s Well-being Scale, this work strengthens the research methodology in the field of well-being for older adults. The results provide a solid foundation for future studies, allowing comparisons and in-depth explorations into the dimensions of well-being identified as crucial for this demographic group. Additionally, the identification of significant well-being differences based on demographic variables such as age and gender provides valuable insight into how well-being needs vary within the older adult population. This information is crucial for the development of inclusive and tailored pedagogical strategies that can address the specific needs of subgroups within this population. Finally, the study contributes to the field of education for older adults by suggesting specific pedagogical interventions based on the findings. These recommendations not only have the potential to improve the quality of life and personal satisfaction of older adults but also serve as a guide for educators and administrators in planning and implementing effective educational programs sensitive to the needs of this group.

There is no financial interest or conflict of interests.