Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Roger Zintchem*1,2,3 and Aurore Margat1

Received: April 24, 2023; Published: May 05, 2023

*Corresponding author: Roger Zintchem, Nursing Sciences Research Chair, Laboratory of Educations and Health Promotion (LEPS UR 3412), UFR SMBH, Sorbonne Paris Nord University, 1 Rue de Chablis, Avicenne-Jean Verdier Nursing Training Institute, CFDC, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, 1-7 Promenade. Jean Rostand, 93000 Bobigny, France and Animal Physiology Laboratory, Department of Biology and Animal Physiology, Faculty of Science, BP 812, University of Yaoundé I, Yaoundé, Cameroon

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2023.50.007919

Advanced practice care is an evolution of the nursing profession for a better management of health problems such as the aging of the population, the chronicization of diseases and polypathologies. It is a new form of paramedical care, which offers career opportunities in the clinical and diagnostic field, with the opportunity for autonomy and recognition [1]. By revealing that 80% of diagnoses were made on the basis of anamnesis, W. Osler advocated that “Just listen to your patient, he is telling you the diagnosis [2]. With the development of scientific and technical innovation, the collection of clinical data from the patient remains essential but is no longer sufficient to make an accurate diagnosis in advanced practice nursing. Paraclinical examinations are a complement whose reading and interpretation by the practitioner remain the best recourse to make a more refined diagnosis, especially in the case of illness. Indeed, 70% of important decisions concerning the management of a patient require the interpretation of clinical examinations and 70% of the elements of the electronic (or paper) file are derived from them [3]. However, the challenge lies in the art of selecting the appropriate biological and/ or radiological and/or electromagnetic paraclinical examination. The paraclinical examination is intimately linked to the clinical examination and is a function of the presumed diagnosis, its interpretation can be based on the use of cognitive strategies and research data. Indeed, like any health care practitioner, the advanced practice nurse can use shared clinical reasoning and evidence for an optimal interpretation of paraclinical examinations.

A literature search was conducted on bibliographic databases such as Google scholar, Web of Science, CAIRN. Various clinical education sites as well as documents related to nursing education, shared clinical reasoning (Cesiform) and evidence-based readings were also used as support for this study. Two radiologists and two medical biologists of Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris were interviewed to obtain information about their practices as well as the tools and equipment they use. This paper is also a contribution to a book “ L’infirmièreen pratique avancée (IPA) - Pathologies chroniques stabilisées et polypathologies courantes en soins primaires.” [4].

Apart from rapid diagnostic tests (point-of-care tests), paraclinical or complementary examinations are generally performed outside the patient’s bed and may have a diagnostic and/or therapeutic purpose. With the knowledge and techniques increasingly digitized, we distinguish essentially [5]:

1. Imagery: X-rays, ultrasounds, scans, PET-Scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), PET-MRI, positron emission measurements.

2. Biological and biochemical analyses of liquid components, secretas or excretas (blood, plasma, urine, cerebrospinal fluid, sweat, saliva...).

3. Direct research (immediately or after culture) of unicellular or multicellular parasites, bacteria and viruses, or indirectly by the immunological trace that these germs have left in the secretas or excretas, in microbiology, bacteriology, virology, or immunology.

4. Examinations of organs, tissues and devices with the naked eye (dissection, surgery, laparoscopy, endoscopy) or with the microscope in endoscopy and anatomo-pathology.

5. Measurements of normal and/or stimulated physiological activities of systems, organs or tissues: metabolisms, electrocardiogram at rest or during exercise, electromyography, electroencephalogram, functional respiratory tests at rest or during exercise, venous and arterial doppler, urodynamic examinations, audiometry.

6. Psychological or psychotechnical tests.

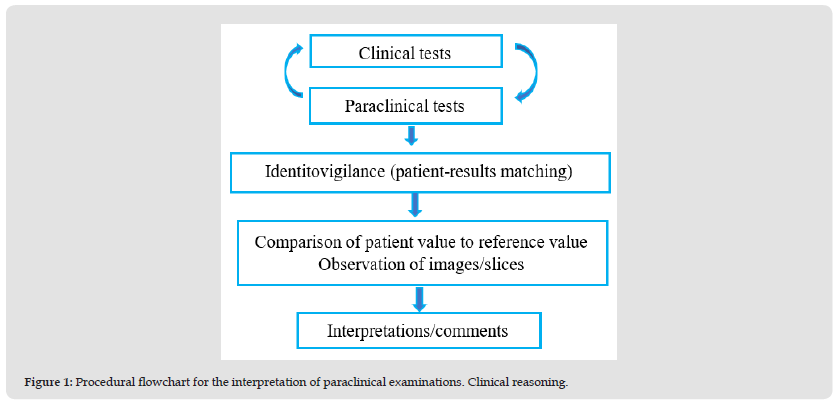

The main objective of paraclinical examinations is the interpretation of anomalies. This is difficult if the evaluation of the reliability of the different paraclinical techniques is questionable [5]. The choice and method of interpretation are therefore dependent on the objectives. The interpretation of laboratory results may involve two more or less integrated processes of shared clinical reasoning (inductive- hypothetical-deductive) and evidence-based practice. The practitioner, after interpretation and according to his field of competence, must explain these results to other health professionals and to the patient (and/or his or her entourage), whose sensitivity and specificity guide the overall and multidisciplinary management in a clinical context. Classically, advanced practice nursing identifies the patient and verifies the concordance between this identity and the prescribed paraclinical examinations, in accordance with the clinical data and the results of the two examinations (identity vigilance). Then, in his clinical reasoning, he compares the patient’s data with the reference values (for biological examinations) or observes the radiological images (contrasts, slices, organ features, display mode) to interpret them [6] (Figure 1). In all cases, the practitioner uses the usual or physiological data of the healthy person, and reference data, taking into account inclusion or exclusion criteria such as age, sex, origin, activity and pathology of the patient. It also takes into account the specialty and the context (hospital, ambulatory, acute, chronic).

Figure 1 Procedural flowchart for the interpretation of paraclinical examinations. Clinical reasoning.

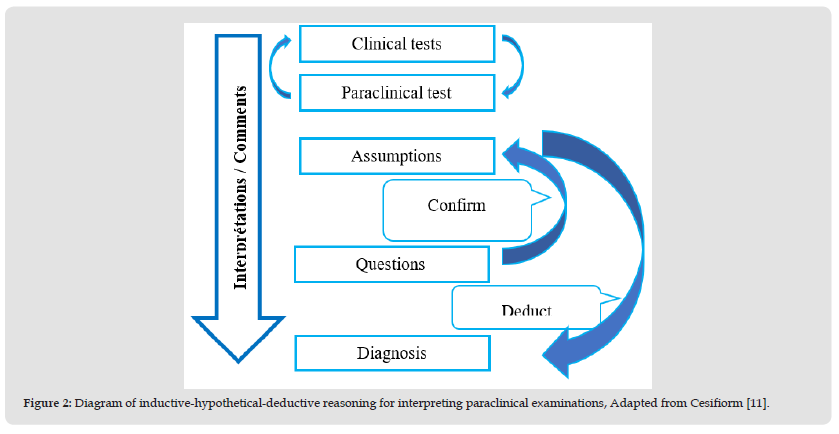

Clinical reasoning constitutes “the thinking and decision-making processes that enable the clinician to propose a course of treatment in a specific context of health problem resolution” [7]. It is a set of cognitive processes, whether conscious or unconscious, which enable the clinician to formulate a working hypothesis and a therapeutic management plan based on a patient’s health problem [8]. This reflective approach gives the advanced practice nurse the ability to act appropriately in a problem-solving context (interpretation of paraclinical examinations in this case). It includes the collection, interpretation and verification of data and, for each action, integrates the analysis of risks, benefits and patient preferences [8,9]. Clinical reasoning can be based on Cariou’s inductive-hypothetico-deductive sequence [10-12]: clinical data-paraclinical data-hypotheses-inferred consequences-results to be analyzed-interpretation-conclusion-rebutted or corroborated hypotheses. The advanced practice nurse draws on clinical data obtained from the patient through observation, palpation, for example. These data direct him or her to paraclinical examinations from which, through the inductive approach, he or she compares the clinical data to the paraclinical data in order to interpret them to make a diagnosis. In the deductive approach, the physician may formulate hypotheses that can be refuted or corroborated in order to deduce the consequences or observable results that will be subjected to analysis and interpretation to make a diagnosis (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Diagram of inductive-hypothetical-deductive reasoning for interpreting paraclinical examinations, Adapted from Cesifiorm [11].

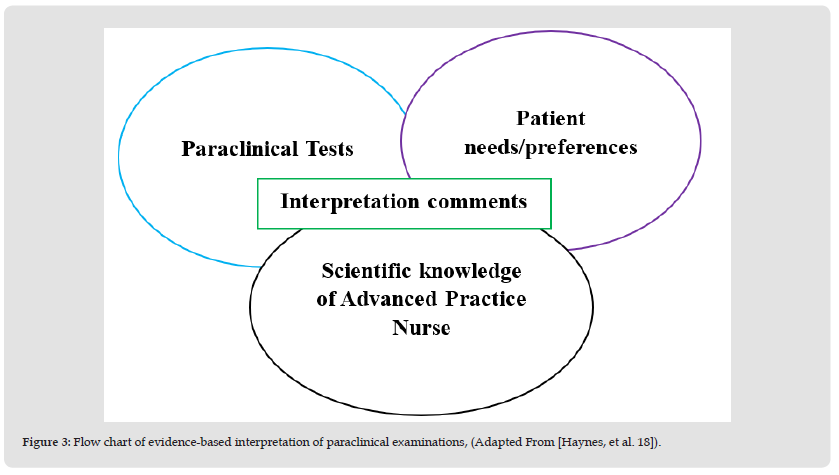

The interpretation of paraclinical examinations can also be based on a number of elements:

1. The patient’s preferences, his needs and expectations in terms of perception and act of care [13], one of the foundations of evidence-based practice, in order to reduce uncertainties.

2. The practitioner’s scientific and practical knowledge is based on his clinical experiences and the evident scientific data. These follow evidence-based guidelines and systematic reviews [14-17].

The advanced practice nurse should, within his scope of practice, draw on the evidence of critical and constructive clinical analysis of the patient. These data are consistent with scientific knowledge, the patient’s values and preferences as well as therapeutic resources. The following diagram (Figure 3) illustrates the advanced practice nurse’s interpretation of paraclinical examinations based on evidence in relation to scientific knowledge, patient needs and clinical examinations.

Figure 3 Flow chart of evidence-based interpretation of paraclinical examinations, (Adapted From [Haynes, et al. 18]).

The aging of the population, polypathology and the chronicization of diseases are at the origin of advanced practice nursing to improve the supply of paramedical care [1,18]. The advanced practice nurse (APN) therefore has more complex and effective theoretical, clinical and decision-making skills [19,20]. These skills can be demonstrated through clinical reasoning which is difficult to define because it lacks a clear and consensual definition [21]. Clinical Reasoning encompasses cognitive strategies and processes that can be used by APN to understand the meaning of patient health data, to identify and diagnose current or potential patient problems and make clinical decisions that contribute to resolve patient’s health problem and to achieve positive patient outcomes [22]. It is a cognitive process, conscious or unconscious, that allows the formulation of a working hypothesis as well as therapeutic management based on a patient’s health problem. It includes the collection, interpretation and verification of data and, for each action, the analysis of risks, benefits and patient preferences [23]. This model of clinical decision making includes four stages (observation, interpretation, reaction and reflection) that are influenced by the context, the nurse’s personal and professional experience, and the relationship with the patient [24]. Clinical reasoning allows the clinician to arrive at a clinical judgment, which is a process of formulating hypotheses that are then confronted with evidence to select the most appropriate hypothesis [25]. Diagnostic errors in the advanced nurse practitioner can result from cognitive biases, rapid interpretation of data and inadequate skills in clinical reasoning and evidence searching [26-28]. Evidence-based practice is an approach that first developed in medicine and other areas of care [29]. The use of evidence by the advanced practice nurse would result in a new nursing practice. Indeed, the nurse’s EBN evidence-based care could become evidence-based advanced practice care (EBAPC) [30].

The interpretation of paraclinical examinations is a set of cognitive activities that can be based on the practitioner’s clinical reasoning as well as on evidence. In advanced practice, the nurse can use these activities and data as well as the patient’s preferences to better interpret the results before making a more appropriate and effective advanced nursing diagnosis in the patient’s clinical pathway. The rise of digital technologies could foster the rise of “tele-practice”, the development of interventional imaging (laparoscopy), augmented reality and artificial intelligence. Faced with this, the human interpretation of paraclinical examinations, which remains an art, will have to be readjusted, both for nurses in advanced practice and for other practitioners.