Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Oumarou Riepouo Mouchili1, Sylvin Benjamin Ateba2*, Edwin Mmutlane3, Derek Tantoh Ndinteh3, Constant Anatole Pieme4, Stéphane Zingue3,5,6 and Dieudonné Njamen1,3

Received: June 27, 2022; Published: July 20, 2022

*Corresponding author: Sylvin Benjamin Ateba, Department of Biology of Animal Organisms, Faculty of Science, University of Douala, P.O. Box 24157 Douala, Cameroon

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2022.45.007172

Background: Osteoporotic fractures are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in post-menopausal women. Lannea acida (Anacardiaceae) is a plant traditionally used to treat bone related disorders. In our previous study, an ethanolic stem bark extract of Lannea acida prevented postmenopausal osteoporosis in ovariectomized Wistar rat model. Based on this preceded results, the present study has been designed to evaluate the capacity of that extract to improve bone-fracture healing in estrogendeficient Wistar rat model of osteoporosis.

Material and Methods: Sham-operated (SHAM) and ovariectomized (OVX) female rats were fractured (30 days post-ovariectomy), divided into 6 groups (n = 5) and then treated by gavage for 60 days. SHAM and OVX controls receiving distilled water, OVX rats treated with estradiol valerate (E2V) at 1 mg/kg BW/day, and three OVX groups respectively treated with L. acida at 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg BW/day.

Results: Ethanol extract of L. acida extract prevented the OVX-induced decrease in femur weights compared to OVX group. It increased calcium and inorganic phosphorus levels and reduced ALP activity in both serum and bone of OVX-fractured animals. Compared to the OVX-fractured animals, it promoted a bone callus formation and union. It increased the trabecular thickness and a quasi-normal trabecular bone network was observed at the fracture site. Moreover, it also improved the fractured bone oxidative stress status.

Conclusion: This study demonstrated for the first time that L. acida extract promotes bone fracture healing in osteoporotic Wistar rats.

Keywords: Lannea Acida; Bone Fracture Healing; Postmenopausal Osteoporosis; Drill-Hole; Oxidative Stress

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease that affects bone quality through a reduction of bone mineral contents and density, and an alteration of the architecture. These events result in increased bone fragility and higher fracture risk [1,2]. In postmenopausal women, endogen estrogen deficiency plays a central role in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis and resulting fractures represent the major cause of morbidity and mortality in that women [3]. On a global scale, the increase in women life expectancy induces a dramatic rise in osteoporotic fracture incidence. Yet in 2013, the annual number of osteoporotic fractures worldwide was estimated to 10 million, with two-thirds in women [4]. This number is expected to increase over the coming years or decades as populations steadily age. Colossal medico-economic consequences are associated with osteoporotic fractures. Williamson, et al. [5] estimated to US$43669 per patient, with immediate inpatient care costing on average $13331, the global health and social care cost in the first year following a hip fracture. For this period, fracture incurs healthcare costs of more than $30,000 in US, of which $3000 will be paid by the patient [6]. In UK, in addition to the costs of disability (long-term social support for survivors), direct health costs are estimated to £4.3 billion for the 50,0000 fragility fractures occurring annually [7]. Apart the heavy economic burden, osteoporotic fractures cause chronic pain, loss of mobility, and loss of independence and death [1].

By contrast to high-income settings, no study has been published on the health costs of fragility fractures in sub-Saharan Africa. The health and socio-economic burden of fractures would likely be much heavier in this low-income setting where there is a lack of health and social systems that facilitate long-term care, a substantial part falling on family and friends. Rather than treat, it is recommended to prevent osteoporotic fractures. In case they occur, comorbidities specific to the patient such osteoporosis strongly interfere with the healing [8,9]. In addition to the mechanical stability, bone fracture healing can be positively modulated by systemic drug therapies [10]. Nowadays, anti-osteoporotic drugs including anti-resorptive and anabolic agents alone or in combination with calcium/vitamin D remain the main treatments [10-12]. However, they display a variable efficacy depending on the type of fracture. For instance, bisphosphonates do not influence the healing after distal radius, hip and vertebral fractures [13]. Anabolic agents accelerate the healing of long bone fractures, while clinical evidence for antiresorptive agents remains unclear [10]. Moreover, safety concerns as well as the poor long-term adherence of these agents substantially contributed to their reduction in prescriptions. Long-term use of bisphosphonates, the most popular antiosteoporotic agents, is associated with increased risk of atypical femur fracture, upper gastrointestinal symptoms and risk of venous thrombosis [14,15]. Nowadays, seeking alternative treatments has become more and more important. Accordingly, medicinal plants have been suggested as an alternative to promote a fast and efficient (without recurrence) bone repair process with no or minimal adverse side effects [16].

Moreover, given their affordability and accessibility, they may play an important role in reducing family economic pressure. In low-income settings, they hold a very important place in the healthcare systems as up to 80 percent of people rely on them for their primary health care. Lannea acida A. Rich (Anacardiaceae) is distributed in Africa and used to treat various ailments including musculoskeletal disorders and gynaecological complains [17,18], to enhance fertility and facilitate parturition [19]. In vitro, the aqueous and methanolic extracts of stem bark induced uterotonic effects through oxytocin receptors [19]. Chronic, non-resolving inflammation is detrimental to fracture healing [20]. Upon fracture inflammatory and ischemic conditions can cause excessive oxidative stress resulting in irreversible damage to cells associated with bone repair [21]. This situation is aggravated by conditions of intrinsic oxidative stress such diabetes and postmenopausal osteoporosis [22-23]. In vivo studies reported inflammatory, analgesic [24], and antioxydative [25] properties of L. acida stem bark extracts. Moreover, our previous study showed that an ethanolic stem bark extract of L. acida exhibited estrogenic properties and prevented bone loss in an ovariectomized rat model of osteoporosis [26]. All these results suggest that L. acida might promote the osteoporotic fracture healing. Therefore, the present study has been designed to evaluate the potential of the ethanolic stem bark extract of the L. acida to promote bone fracture healing in drill-hole injury in estrogen-deficient Wistar rat model of osteoporosis.

The antibiotic penicillin (xtapen®) and diclofenac (Dicloecnu®) were obtained from CSPC Zhongnuo pharmaceutical (Shijiazhuang City, China) and ECNU pharmaceutical (Yanzhou City, China), respectively. The 17β-estradiol valerate (Progynova®) were provided by DELPHARM (Lille, France).

The stem barks of L. acida were collected in Moutourwa (Far- North, Cameroon) in July 2014. The plant sample was authenticated at the national Herbarium of Cameroon (HNC-IRA) with voucher number 40942 HNC.

Healthy, nulliparous and non-pregnant female Wistar rats (2.5- 3 months), from the Animal house of the Department of Animal Biology and Physiology, Faculty of Science, University of Yaoundé 1, Cameroon. They were housed in groups of five in plastic cages and kept at room temperature, under natural illumination. They were given soy free diet and water ad libitum. Animals were handled in accordance to the European Union on Animal Care (CEE Council 86/609) guidelines approved by the Institutional National Ethics Committee of the Cameroonian Ministry of Scientific Research and Technology Innovation.

The air-dried and powdered plant material (2kg) was soaked 3 times in 6L of 95% ethanol at room temperature for 48h. After filtering, the combined solution was concentrated under reduced pressure (40°C, 337 mbar) using a rotary evaporator to obtain 272 mg of extract.

To determine the content of calcium, magnesium, potassium, sodium and phosphorus in the extract, 0.5 g of L. acida extract was diluted in 10 mL of supra pure HNO3 and placed in the MARS 6 microwave digestion system (CEM Matthew, USA) for 30 minutes. Thereafter, demineralized water was added to the tubes up to a total volume of 50 mL. One mL of this digested sample was diluted in 9 mL of 1% HNO3 in falcon tubes. In reference to calibration curves of standards, the mineral contents of sample were determined using a Spectro Arcos inductively coupled plasma – optical emission spectrometer ICPOES (SPECTRO Analytical Instruments, Germany).

Animal Randomization, Drill-Hole Femur Injury and Treatment: Before the bilateral ovariectomy, vaginal smears of each animal were daily performed for 12 consecutive days to be sure that they are normocyclic. Thereafter, twenty-five of them were ovariectomized (OVX) under anaesthesia (10 mg/kg diazepam and 50 mg/kg ketamine, i.p.), while 5 were sham-operated (SHAM). To assure the situation of estrogen depletion and constant presence in diestrus step, the vaginal smears of the ovariectomized animals were daily checked for five consecutive days from the day 14 after ovariectomy. Thereafter, animals were divided into 6 groups of five animals each (n = 5). Fractures of the proximal femur are the osteoporotic fractures with the highest morbidity and mortality [12]. Yousefzadeh, et al. [27] reported that 30 days is the time needed for inducing osteoporosis in rat femur after bilateral ovariectomy. Accordingly, thirty days after the ovariectomy a femoral drill-hole injury was created in all ovariectomized rats as described by Ngueguim, et al. [28]. Briefly, following a 1-cm long skin and musculature incision, and the exposure of the surface of the femur under anaesthesia (diazepam and ketamine), a 1-mm diameter hole was created by inserting a drill bit into the anterior portion of the diaphysis. Thereafter, animals were sutured and submitted from the very next day to a 60-day (once daily at 4 - 5 p.m.) oral treatment. The animals were weighed once weekly. Group I (SHAM) and Group II (OVX: ovariectomized rats serving as negative control) received distilled water; Group III (E2V: OVX rats serving as positive control) received 1 mg/kg estradiol valerate; Group IV, V and VI (LA 50, LA 100 and LA 200) were OVX animals treated with L. acida extract at the doses of 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg, respectively. At the end, the rats were sacrificed under anaesthesia (10 mg/kg of diazepam and 50 mg/kg of ketamine, i.p.) after an overnight fast and the blood samples collected. The uterus, vagina and femurs were peeled off to remove the surrounded tissues. After weighing uterus and femurs, all these tissues were fixed in 10% formaldehyde.

After washing in NaCl 0.9%, the proximal portion of the left femur was cut and weighed (0.5 g). The tissue was then homogenized in ice-cold medium using a glass Teflon-Potter and 3 mL of deionized water. After centrifuging at 3000 rpm at 5°C for 15 min, the supernatant was collected for estimating the antioxidant activity. Catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activities as well as the ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) were determined according to the methods of Wilbur, et al. [29], Ellman [30], and Benzie and Strain [31], respectively. Calcium and inorganic phosphorus contents as well as alkaline phosphatase activity were also measured using Biolabo (Maizy, France) reagent kits.

The blood samples collected in EDTA tubes were analysed using a Mindray BC-2800 Auto Haematology Analyser. The samples in dry tubes were centrifuged at 3500 rpm at 5°C for 10 min, and the serum analysed to measure the serum calcium and inorganic phosphorus contents as well as the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity using reagent kits from Biolabo (Maizy, France).

The bone callus formation was evaluated as described by Ngueguim, et al. [28]. Briefly, the femur was exposed for 5 milliseconds to X-rays emitted by an Allengers X-ray machine (maximum voltage 125 Kv, main voltage 55 Kv, filtration 0.9 Al/75 (permanent) at a distance of 1 m). An AGFA CR 30-Xm detector (CRAGFA, Belgium) was used for obtaining and analysing the images.

A Zeiss Axioskop 40 microscope equipped with an AxioCam MR digital camera connected to a computer allowed the analysis of 5 μm sections of paraffin-embedded uterus and femur using MRGrab1.1 and Axio Vision 3.1 softwares (Carl Zeiss, Hallbergmoos, Germany). The sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin.

All results were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) and analysis Graphpad Prism 5.03. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Dunnett’s post hoc test were used. p value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Table 1 summarizes the contents of potassium (K), phosphorus (P), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca) and sodium (Na) found in L. acida extract. Potassium was found to be the most abundant mineral (7387.91 ± 80.19 μg/g) followed by calcium (1657.20 ± 52.65 μg/g). The abundances of sodium, phosphorus and magnesium were 979.95 ± 4.45, 680.11 ± 3.38 and 343.99 ± 2.05 μg/g, respectively.

Effects on Uterus and Vagina: Table 2 depicts the effects of the ethanolic extract of L. acida on uterus and vagina. A significant (p < 0.001) reduction of uterine relative wet weight as well as uterine and vagina epithelial heights was observed 90 days after ovariectomy in OVX animals compared with sham-operated (SHAM). Compared with OVX group, a 60-day treatment with the extract of L. acida from day 31 significantly increased (p < 0.05) the uterine (at 50 and 100 mg/kg) and vaginal (at 100 and 200 mg/kg) epithelial heights.

Table 2: Mineral composition of the ethanolic extract of L. acida.

Note: SHAM = normal animals receiving distilled water; OVX = Ovariectomized rats receiving distilled water; E2V = ovariectomized rats treated with estradiol valerate (1 mg/kg); L. acida = Ovariectomized rats treated with L. acida extract at the doses of 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg, respectively. Data are expressed as mean ± ESM (n = 5); *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01 and. ***p < 0.001 as compared with SHAM group. ###p < 0.001 and #p< 0.05 as compared with OVX group.

Effects on Femur Weight: A 90-day of estrogen depletion led to a significant reduction (p < 0.01) of the femur weight as compared with SHAM group (Table 2). At 50 and 100 mg/kg of L. acida extract, the femur wet and dry weights were significantly higher (p < 0.5) than that in OVX group following a 60 days’ oral treatment from the day 31.

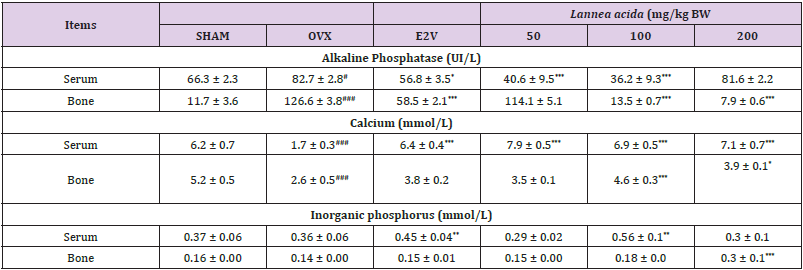

Effects on Some Biomarkers of Serum and Bone: Table 3 shows an increased (p < 0.05) alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity in both serum and bone 90 days after ovariectomy as compared with normal rats. The 60-day treatment with L. acida from day 31 after ovariectomy led to a lower ALP activity (p< 0.001) in serum (at 50 and 100 mg/kg) and bone (at 100 and 200 mg/kg) as compared with OVX group. Calcium levels in bone and serum were significantly lower (p< 0.001) in OVX animals as compared with SHAM group 90 days after ovariectomy. Compared to the OVX group, the serum calcium levels of the L. acida extract treated groups significantly increased (p< 0.001). The values were even higher than that observed in SHAM group. In bone, a significant increase was observed at the doses of 100 and 200 mg/kg group (p < 0.05). On the other hand, E2V-treated rats exhibited a higher (𝑝< 0.001) serum level of calcium, while no significant variation was observed in the femur. Regarding inorganic phosphorus, 90 days of endogenous estrogen depletion did not affect the bone and serum levels of inorganic phosphorus as compared with the SHAM group. Treatment with E2V (1 mg/kg) and L. acida (100 mg/kg) from the day 31 exhibited a higher level of inorganic phosphorus in serum as compared with OVX group (p < 0.01), while only 200 mg/kg of L. acida extract increased (p < 0.001) this parameter in bone.

Table 3: Effects of the ethanol extract of L. acida on some biomarkers of bone and serum after 60 days of treatment from day 31.

Note: SHAM = normal animals receiving distilled water (vehicle); OVX = Ovariectomized rats receiving distilled water; E2V = ovariectomized rats treated with estradiol valerate (1 mg/kg); L. acida = Ovariectomized rats treated with L. acida extract at the doses of 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg BW, respectively. All animals were fractured. Data are expressed as mean ± ESM (n = 5); *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01 and. *** p < 0.001 as compared to SHAM group. ###p < 0.001 and #p< 0.05 as compared to OVX group.

Figure 1:

(A) Effects L. acida ethanol extract on the catalase,

(B) Glutathione peroxidase and

(C) FRAP activities in bone.

GPx = glutathione peroxidase; FRAP = Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power; SHAM = normal control group receiving the vehicle (distilled Water), OVX = negative control group receiving the vehicle (distilled Water); E2V = OVX rats that received estradiol valerate (1 mg/kg BW); L. acida = OVX animals treated with de L. acida at the doses of 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg BW, respectively. Data expressed as mean ± SEM (n= 5); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 as compared to OVX group. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, and ### p < 0.001 as compared to SHAM group.

Ninety days after ovariectomy, a non-significant reduction (13.6%) of catalase (CAT) activity was observed in OVX rats as compared with the SHAM animals (Figure 1A). Treatment with E2V and L. acida (50 and 200 mg/kg) from the day 31 led to a lower CAT activity than that observed in OVX group (p< 0.001). However, the extract at 100 mg/kg significantly (p< 0.001) augmented the CAT activity at a value higher than that in the SHAM group. Compared with SHAM group, glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity and the Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) considerably diminished (p< 0.01) in bone of OVX rats (Figures 1B & 1C, respectively). The oral administration of E2V and L. acida for 60 consecutive days at all tested doses significantly (p < 0.001) increased GPx activity and FRAP as compared with the OVX group. The values of FRAP and GPx in all groups receiving the extract were close and higher than that of the SHAM group, respectively.

Figure 2: Effects L. acida ethanolic extract in the bone radiographies and histology. SHAM = normal control group receiving the vehicle (distilled Water); OVX = negative control group receiving the vehicle (distilled Water); E2V = OVX rats that received estradiol valerate (1 mg/kg BW); TB = trabecular bone; CB = cortical bone; BM = bone marrow; L. acida = OVX animals treated with de L. acida at the doses of 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg BW, respectively. Data expressed as mean ± SEM (n= 5); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 as compared to OVX group. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, and ### p < 0.001 as compared to SHAM group.

Radiographies of injured femurs showed a partial healing of bones in untreated OVX animals compared to the SHAM group. Ovariectomized and fractured rats that received E2V (1 mg/ kg) and L. acida at all the doses had total bone healing (Figure 2) characterized by a total callus formation and a complete bone union. Femurs in OVX group showed a deterioration of the microarchitecture as compared with the SHAM group. This was evidenced by the larger resorption lacunas (Figure 2). However, L. acida extract at all the tested doses improved the bone microstructure after fracture compared to OVX group. In fact, the histological sections of bones of these animals showed a quasinormal trabecular bone network. Furthermore, measurement of the trabecular bone thickness showed a significant (p< 0.05) reduction of trabecular bone thickness in OVX animals compared to the SHAM group. E2V and L. acida extract at all the tested doses for 60 days significantly (p< 0.001) increased the thickness of the trabecular bone as compared with the OVX rats.

As far as haematological parameters are concerned, no significant variation was found in all parameters between the different groups (Table 4). Exception made for the white blood cell count, which was significantly decreased in the negative control group compared to the normal group.

Table 4: Effects of the ethanolic extract of L. acida extract on the hematological parameters.

Note: SHAM = normal animals receiving distilled water (vehicle); OVX = Ovariectomized rats receiving distilled water; E2V = ovariectomized rats treated with estradiol valerate (1 mg/kg); WBC = white blood cell count; RBC = red blood cell count; MCV = mean corpuscular volume; MCH = mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC = mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; L. acida = Ovariectomized rats treated with L. acida extract at the doses of 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg BW, respectively. All animals were fractured. Data are expressed as mean ± ESM (n = 5); *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01 and. ***p < 0.001 as compared to SHAM group. ###p < 0.001 and #p< 0.05 as compared to OVX group

The bone-fracture healing capacity of the ethanolic stem bark extract of L. acida was investigated using a drill-hole femur fracture in postmenopausal Wistar rat model of osteoporosis. Bilateral ovariectomy is a widely accepted model for evaluating postmenopausal complications as well as the effects of substances on these complications. The lack of ovarian estrogen production for 90 days induced a significant reduction in uterine wet weight as well as uterine and vaginal epithelial heights in OVX group compared to SHAM group. This result is in accordance with many reports [26,32,33] and validates the bilateral ovariectomy. The 60-day treatment with L. acida extract had no effect on uterine wet weight but significantly increased the uterine and vaginal epithelial heights. This result suggests the presence of estrogenlike phytoconstituents in the extract and confirm the estrogenic potential of L. acida observed in our previous report [26].

Patient-related comorbidities such as osteoporosis contribute to bone fracture-healing complications [8]. By managing them bone healing can be improved. The significant reduction in femur mass and calcium content as well as the increase in bone alkaline phosphatase activity observed in OVX group as compared with SHAM group indicate the osteoporosis status in these animals. The process of consolidation and bone remodelling of a fracture is strictly dependent on bone turnover and the calcium and phosphate metabolism [10]. L. acida ethanolic extract significantly increased calcium and inorganic phosphorus levels in bone. Osteoblasts are responsible for the osteoid matrix formation and, through the production of non-collagenous proteins, initiate and regulate its mineralization. Therefore, the increase of bone calcium and inorganic phosphorus contents following treatment with L. acida is an indicator of bone formation. The higher the calcium and phosphorus contents, the greater the bone density and strength. L. acida extract also induced a significant increase of serum calcium and inorganic phosphorus levels suggesting an elevated intake of that minerals.

The analysis of this extract showed high amounts potassium, calcium, inorganic phosphorus and magnesium suggesting that the extract provides, at least in part, the minerals (calcium, inorganic phosphorus) necessary for the bone mineralization. Studies indicated that in addition to activate vitamin D, magnesium promotes osteoblast proliferation [34,35], while a high dietary intake of potassium is beneficial to bone health even in people with low dietary calcium intake [36]. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), a specific biomarker of bone formation secreted by osteoblast during bone maturation [37], increased both in serum and femur of OVX-fractured rats compared to sham-operated animals. L. acida extract at the tested doses significantly reduced the ALP activity in bone and serum compared to OVX group. Several studies correlated the reduction of bone and serum ALP activity with the process of fracture healing [28,38,39]. Normal fracture healing is generated by increased osteoblastic activity, that secretes large quantities of ALP involved in the bone formation and mineralization [38].

Following a fracture, there is an acute increase in ALP activity, then it decreases with the formation of bone callus to return to normal when it ceases [38]. The faster bone healing occurs, the faster the ALP activity decreases. In line with this, it appears that compared to the OVX-fractured control animals, there is an acceleration of bone healing in OVX-fractured animals treated with L. acida extract. The radiographies of femurs from animals in this study showed a healing of fractures, except for the femur of OVXfractured animals, where the healing was not complete. According to our results, microarchitectures of bone of OVX-fractured rats were disorganized, with decrease in trabecular bone thickness. E2V and L. acida extract treatment reversed this bone disorganization and increased trabecular bone thickness compared to that observed in OVX-fractured control group. According to Potu, et al. [40], osteoporosis is characterized by reduction in trabecular and cortical bone thicknesses. L. acida ethanol extract inhibited bone lost and microarchitecture alteration by the same way improved bone fracture healing.

Oxidative stress has been suggested to be a mediator and indicator of osteoporosis [41-44]. It also been involved in the ischemia-reperfusion processes, especially during the callus formation, that occur after a fracture [45,46]. Sandukji, et al. [47] showed that antioxidant treatment improves bone parameters and oxidative stress related markers in patients with long-bone fractures, and thus might be beneficial in the healing. A decrease in GPx activity and FRAP was observed in OVX-fractured rats compared to SHAM group, while bone catalase (CAT) did not change. This result indicates the occurring of the oxidative stress in femur of OVX-fractured rats. Treatment of these animals with L. acida ethanolic extract induced a significant increase in CAT (at 100 mg/kg) and GPx (at all tested doses) activities suggesting an antioxidant activity in bone. On the other hand, the extract at all tested doses significantly increased bone FRAP in OVX-fractured animals. The FRAP measures the total antioxidant capacity of the antioxidants present in the sample and able to reduce ferric ion (Fe3+) involved in the generation the most potent hydroxyl radical. Accordingly, our results suggest that the ethanolic extract of L. acida increased non-enzymatic antioxidants and reduced lipid peroxides in the bone tissue.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the capacity of that extract to improve bone-fracture healing in estrogen-deficient Wistar rat model of osteoporosis. The extract reduced the alkaline phosphatase activity, increased calcium and inorganic phosphorus contents and improved the oxidative stress status in bone. In addition, a quasi-normal trabecular bone network at the fracture site accompanied the positive effects of the L. acida extract on callus formation and fracture healing. All these results suggest that the ethanol extract of stem bark of L. acida improves bone fracture healing in ovariectomized Wistar rat.

None declared.

All the authors accepted the responsibility of the manuscript’s content and approved the submission.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.