Abstract

Introduction: Optimal extrauterine growth continues to be a major subject of debate among experts. If there is 19 more weight gain up to the 36 weeks (w) post-menstrual age (PMA) reaching the same birth percentile, does the 20 head circumference (HC) grow at the same rate and reach the same level of recovery during the hospital stay? 21

Materials and Methods: From 2016-2019, babies from Epic Latino network less than 33w gestational age (GA) 22 and who survived to 36w PMA and had information on the database were included, we excluded any cause of 23 abnormal HC and incongruent data. We compared changes in Z-scores from birth to 36w PMA for weight and 24 HC using the Fenton Growth Chart. We measured a nonparametric (Spearman) correlation between these two 25 measurements). We then compared all relevant related factors to growth including changes in Z-score for weight 26 using groups of 0.4 increments/ decrements. All these where then incorporated in a multiple median regression 27 model to adjust for potential confounders. 28

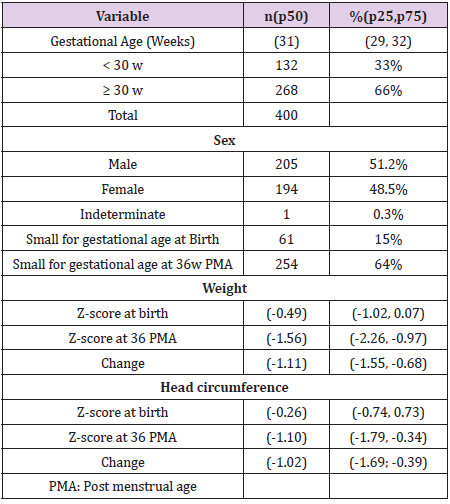

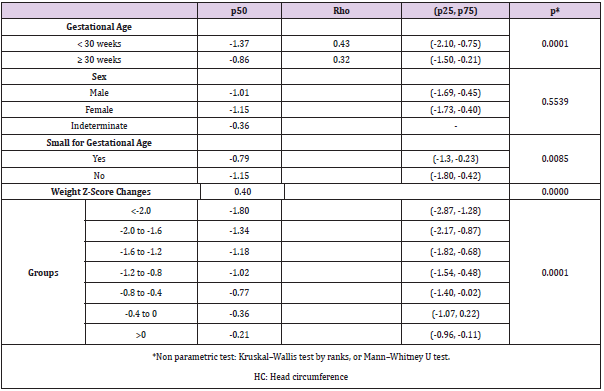

Results: 400 patients were included with a birth median Z-score for weight of -0.49 (IQR -1.02, 0.07) and for HC 29 -0.26 (-0.74, 0.73). At 26 w PMA Z-score where -1.56 (-2.26, -0.97) for weight and -1.10 (-1.79, -0.34) for HC. 30 Overall, the Change in Z-score was -1.11 (-1.55, -0.68) for Weight and -1.02 (-1.69; -0.39) for HC with a positive 31 correlation rs = 0.40, p <0.01. Cases with a GA < 30w had more negative median changes in HC (-1.37 vs -0.86, p 32 < 0.01), but small for gestation age (SGA) did better that the other babies (-0.79 vs -1.15, p = 0.01). Onley Weight 33 to HC changes where independently related after multiple median regression analysis (p <0.01) but not GA (p = 34 0.06) or SGA (0.13). 35

Conclusion: We confirm that changes in weight Z-score from birth to 36w PMA positively correlate with head 36 growth and are related even when controlled for GA or SGA. This has implication on head growth and 37 consequently a probable favorable neurological outcome that needs to be confirm in other cohorts. If confirm, 38 optimal extrauterine grow should be based on Z score weight/HC gain not on absolute or relative daily gain and 39 aim should be to regain birth Z-scores.

Keywords: Very premature infants; Z-score on weight and head circumference; Epic Latino

Abbreviations:PMA: Post-Menstrual Age; HC: Head Circumference; GA: Gestational Age; TPN: Total Parenteral Nutrition; EN: Enteral Nutrition; SGA: Small for Gestational Age; DOHaD: Developmental Origins of Health and Disease

Introduction

The ideal nutritional goals for small premature infants have

not yet been established [1]. This has led to a large variability

of nutritional practices in neonatal units. In addition to this,

strategies to improve weight gain, such as breast milk fortifiers,

are not commercially available in some parts of Latin America or

are so expensive that they are not covered by insurance. Some

authors have suggested that falling below the 10th percentile at

discharge in a given growth chart is an indication of poor nutrition.

Nevertheless, at birth often low Z-scores represents the event that

led these premature babies to be born early, and it is not uncommon

for Z-score to remain low, frequently related to poor intrauterine

growth, but also 10% or 3% of the population has that weight, by

definition, within the normal distribution curve. Therefore, it is

frequent to see patients below the 10th or 3rd weight percentile

when discharged from neonatal units. If these patients are born

close to the 10th percentile, when the expected weight loss occurs,

many of them will fall below this 10th percentile. This physiological

drop in the first few days has been attributed to a contraction in

volume of extracellular space that is expected to occur and is

greater the smaller the premature infants, because they have a

higher percentage of interstitial fluid [2].

However, what percentage of this weight loss is attributable

to volume contraction and what to malnutrition due to low

intake? During this first week of life, a fall in weight is expected

[3] but, if there is no malnutrition, the head circumference (HC)

and length should continue to increase. Then why do we see

sometimes a flattening of HC and length growth during the first

week [4]? Nevertheless, we also have to acknowledge that these

two anthropometric measurements are not very accurate due to

the difficulty of measuring them with precision [5]. The second

stage where poor growth can often occur is during the transition

between total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and enteral nutrition

(EN). Generally, TPN is reduced too quickly and EN is not increased

quickly enough [6]. Also, the volume of nutrition that a premature

infant generally receives for most of their stay is limited by volume

and not by the amount of nutrients they need to continue to grow

as if they were still in utero. This volume limitation is arbitrary and

has not been adequately studied [7]. A few studies with a greater

enteral volume intake, have shown better growth without adding

any complications [8-10]. Finally, the role of fortifying human milk

could be part of the problem, with early vs late introduction of

fortifiers as an example [11], also remembering the wide variability

of the nutrient content of human milk [12].

It is important to highlight that although there are many reasons

to want adequate growth, perhaps the most important reason is

that better HC growth is associated with better neurodevelopment

[13-17].

Naturally, the opposite effect of excess nutrition is a concern

among clinicians [18]. Studies of metabolic syndrome have become

frequent in recent years [19-21], but these are population studies

that have identified a risk at birth referring to people born with

low weight, not from excess nutrition in the neonatal units [22].

Unfortunately, the composition of growth in premature patients

is abnormal with a poor distribution of body fat [19], but if this is

due to the total amount of nutrients or the imbalance and timing

between them is still a matter of debate. Is it due to a poor protein

intake [23,24] during the first week for example or to an inadequate

total nutrition thereafter? These questions remain unanswered. We

do not know if poor postnatal weight increase during hospital stay

affects HC growth to the same extent, protecting it, as sometimes

occurs in intrauterine growth [25] but on the other hand, if there is

any catch-up in weight up to 36 weeks reaching the birth percentile,

does the head circumference grow at the same rate and achieve

the same catch-up? In the EpicLatino Network, we use changes in

Z-score weight between birth and discharge to monitor quality of

growth in premature infants under 33 weeks in our units, but the

relation to other measures of growth are still lacking. All the units

have surrendered an approval of their etic committees to include

their data in this database. Taking into account these various stages

where there may be poor postnatal growth in very premature

infants, we believe it is important to determine what are the growth

results in these patients at a standard post menstrual age (PMA),

and if it reflects the growth of their HC.

Materials and Methods

The EpicLatino Network is a prospective quality improvement database of neonatal intensive care units across Latin America based on the CNN (Canadian Neonatal network) case report form. It collects data from 23 units since 2016 from 5 countries (Argentina, Colombia, Curaçao, Ecuador, Mexico, and Paraguay). This is a retrospective cross-sectional analysis in all babies registered in this database from January 2016 to December 2019. We included all babies less than 33 weeks of gestational age (GA) with complete information of those that were born or admitted in the first 24 hours after birth and survived to 36 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA). We excluded any case of readmission after initial discharge, children on palliative care, head malformations, or any cause or ventricular enlargement, and cases with missing/incongruent data (any cases with more than 3 points changes in Z-scores at birth or at 36w PMA in weight or HC. Also, any inverse growth, missing values, HC growth if greater than 2cm/week or weight increase of greater than 700gr/week). The Z-scores were calculated with Fenton charts 2013 at birth and at 36 weeks PMA, adjusted for gender; changes in Z- scores for each patient were obtained and graphed for interpretation. We measured the correlation for nonparametric measurements for the whole group. We then compared HC changes using non parametric analysis (Kruskal–Wallis test by ranks, or Mann–Whitney U test) with GA by groups (<30 w, ≥ 30 w), sex, small for gestational age (SGA) and we grouped changes in Z-score for weight starting at 0 by 0.4 increments/decrements until >0 or <-2.0. We then constructed a multiple median regression analysis to compare HC to weight changes to adjust for GA and SGA. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A scatter plot and a fox-plot where created for interpretation. We use STATA 13 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LP) for calculations.

Results

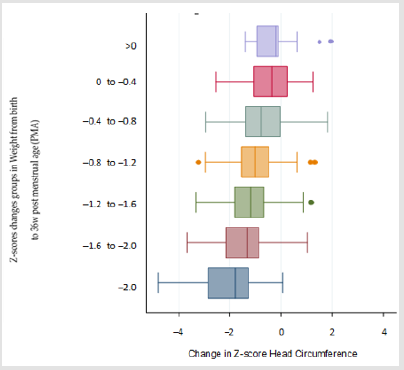

We included 400 out of 447 patients who met the inclusion criteria, we excluded 23 cases due to ventricular enlargement, 8 due to changes of more than 3 points and 16 cases due to inverse growth as compared to discharge, HC greater than 2cm/ week or weight increase greater than 700gr/week. Descriptive demographics including incidence of SGA, sex, and Z-score results for weight and HC at birth, 36 weeks PMA and absolute changes are shown in (Table 1). When we compared Z-scores changes of weight and HC, we found a positive Spearman correlation of rs = 0.40 as shown in (Figure 1). When we compared sex, GA, and changes in weight by group (Table 2). We found that HC median Z-score change is greater and related to less GA (< 30 w vs ≥ 30 w; p<0.01), weight Z-score change (p < 0.01; (Figure 2)) and SGA babies (p =0.01). Next we then created a lineal median regression model using the Changes in Z-score for HC and weight, GA and SGA and found that weight changes in Z-score where independently related to changes in Z-Score for HC (p < 0.01) but not GA (p= 0.06) or SGA (0.13).

Figure 1: Scatter plot is shown with fitted values and trend lines for Z-scores changes in weight and HC at birth at 36w

Figure 2: In the Y axis, marginal plot after linear regression represents mean and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of Z-scores groups of changes in weight from birth to 36w post menstrual age (PMA) arranged by categories of 0.4 changes in Z-score. Fitted values of Z-score head circumference (HC) changes from birth to 36 weeks (w) PMA are seen in X axis

Discussion

We found an overall positive correlation between changes in weighted Z-score and those in HC, and an independent relation after adjusting for GA and SGA status. The poor growth during hospitalization in very preterm neonates has clinical relevance since the associated caloric and protein deficits not only result in slower growth velocity, but are also associated with major neonatal morbidities, including bronchopulmonary dysplasia, retinopathy of prematurity, and the already mentioned impaired neurodevelopment as extensively published. Along the same line, epidemiologic studies have described additional long-term health consequences of growth restriction and low birth weight, such as an increased risk of cardiovascular (hypertension, microvasculopathy), renal (acute or chronic renal injury) and metabolic morbidities (insulin resistance, liver steatosis) in adult life, covered in the concept of developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) [26]. Current evidence suggests that even brief periods of relative undernutrition during a sensitive period of development have significant adverse effects on later development [27]. Even if theoretically, adequate nutrition is desirable, the neonatologist still do not deliver adequate nutrition in fear of metabolic problems [28]. As stated by the Pre-B taskforce [26] “Whether it is more appropriate to reassign a new z score trajectory target once preterm infants decrease their extracellular volume in the postnatal environment, or whether they should return to their birth z score trajectory, remains a theoretical question. Therefore, the use of a weight-gain trajectory beginning after extracellular volume loss, with guidance provided by the size distribution of the fetus, is the most appropriate goal for preterm infants to follow until a more representative and validated growth pattern can supersede this.” Our findings may prove that setting an arbitrary acceptable limit on the upper limit of the weight Z-score catch-up for fear of obesity and metabolic syndromes, without a rigorous study of these patient population, may be a mistake.

Although we cannot rule out that some of these patients may develop a metabolic syndrome in adulthood, most patients with catch up weight Z-score seem to have an adequate anthropometric growth, at least in weight and HC. On the other end, the poor growth many patients have, could add a handicap in the future. It is especially important to continue studying this issue further since very young premature infants with few morbidities have a slower brain growth than those born at term, as reported [29], and a larger HC growth has been associated with better neurodevelopment outcomes [13-17,30]. It would be also important to study the Z score change in length in a large cohort of patients. Whether poor growth is only due to poor nutrition intake during the various stages of growth within the units as described in the introduction or poor quality or nutrient imbalance, is a subject for future research. It should be noted as a limitation that HC measurements are not very accurate at best. Limitations include inadequate clinical practices taking the measurement, the shape of the head (dolichocephaly for example), the measurements being operator dependent, the slow growth meaning small changes are not recorded, and several other factors that influence brain growth that could be playing a role. Some patients have no information on either weight or HC at 36 weeks, limiting the number of patients collected in the network and available for this work. Fortunately, in this paper, each patient is their own control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Angela B. Hoyos, Pablo Vasquez-Hoyos, Carolina Villegas-Alvarez, Maria I. Martinini, Veronica Delgado and Carlos Fajardo; methodology, Angela B. Hoyos, Pablo Vasquez-Hoyos, Marco Belzu-Rodriguez, Carolina Villegas-Alvarez; validation, Angela B. Hoyos, Pablo Vasquez-Hoyos, Carolina Villegas-Alvarez, Maria I. Martinini, Veronica Delgado and Carlos Fajardo; formal analysis, Angela B. Hoyos, Pablo Vasquez-Hoyos, Marco Belzu- Rodriguez, Carolina Villegas-Alvarez, Maria I. Martinini and Carlos Fajardo; investigation, Angela B. Hoyos, Pablo Vasquez-Hoyos; data curation, Angela B. Hoyos, Pablo Vasquez-Hoyos, Marco Belzu- Rodriguez, Carolina Villegas-Alvarez, Maria I. Martinini, Veronica Delgado, Edwin González and Carlos Fajardo; writing—original draft preparation, Angela B. Hoyos, Pablo Vasquez-Hoyos; writing— review and editing, Angela B. Hoyos, Pablo Vasquez-Hoyos, Marco Belzu-Rodriguez, Carolina Villegas-Alvarez, Maria I. Martinini, Veronica Delgado, Edwin González; visualization, Angela B. Hoyos, Pablo Vasquez-Hoyos, Marco Belzu-Rodriguez, Carolina Villegas- Alvarez, Maria I. Martinini, Veronica Delgado, Edwin González and Carlos Fajardo; supervision, Angela B. Hoyos, Pablo Vasquez- Hoyos, and Carlos Fajardo. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding except author’s time.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to Dr. Felipe Fajardo for the grammatical correction of this article and EpicLatino and its Borad of directos.

References

- Riskin A (2017) Meeting the nutritional needs of premature babies: their future is in our hands. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 78(12): 690-694.

- Modi N, Bétrémieux P, Midgley J, Hartnoll G (2000) Postnatal weight loss and contraction of the extracellular compartment is triggered by atrial natriuretic peptide. Early Hum Dev 59(3): 201-208.

- Rochow N, Raja P, Liu K, Fenton T, Landau Crangle E, et al. (2016) Physiological adjustment to postnatal growth trajectories in healthy preterm infants. Pediatr Res 79(6): 870-879.

- Hiltunen H, Löyttyniemi E, Isolauri E, Rautava S (2018) Early Nutrition and Growth until the Corrected Age of 2 Years in Extremely Preterm Infants. Neonatology 113(2): 100-107.

- Bhushan V, Paneth N (1991) The reliability of neonatal head circumference measurement. J Clin Epidemiol 44(10): 1027-1035.

- Miller M, Vaidya R, Rastogi D, Bhutada A, Rastogi S (2014) From parenteral to enteral nutrition: a nutrition-based approach for evaluating postnatal growth failure in preterm infants. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 38(4): 489-497.

- Abiramalatha T, Thomas N, Gupta V, Viswanathan A, Mc Guire W (2017) High versus standard volume enteral feeds to promote growth in preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9(9): CD012413.

- Thomas N, Cherian A, Santhanam S, Jana AK (2012) A randomized control trial comparing two enteral feeding volumes in very low birth weight babies. J Trop Pediatr 58(1): 55-58.

- Kuschel CA, Evans N, Askie L, Bredemeyer S, Nash J, et al. (2000) A randomized trial of enteral feeding volumes in infants born before 30 weeks' gestation. J Paediatr Child Health 36(6): 581-586.

- Travers C, Ambalavanan N, Carlo W, Wang T, Salas AA, et al. (2019) Higher of usual Volume Feeds in Very Preterm Infants: A Randomize Control Trial. In Birgminghham UoAa (Eds.) Pediatric Academic Societies (PAS); Baltimore, Marynald, USA.

- Alyahya W, Simpson J, Garcia AL, Mactier H, Edwards CA (2020) Early versus Delayed Fortification of Human Milk in Preterm Infants: A Systematic Review. Neonatology 117(1): 24-32.

- Wu X, Jackson RT, Khan SA, Ahuja J, Pehrsson PR (2018) Human Milk Nutrient Composition in the United States: Current Knowledge, Challenges, and Research Needs. Current Developments in Nutrition 2(7).

- Belfort MB, Rifas Shiman SL, Sullivan T, Collins CT, Mc Phee AJ, et al. (2011) Infant growth before and after term: effects on neurodevelopment in preterm infants. Pediatrics 128(4): e899-906.

- Sammallahti S, Pyhälä R, Lahti M, Lahti J, Pesonen AK, et al. (2014) Infant growth after preterm birth and neurocognitive abilities in young adulthood. J Pediatr 165(6): 1109-1115e3.

- Neubauer V, Griesmaier E, Pehböck Walser N, Pupp Peglow U, Kiechl Kohlendorfer U (2013) Poor postnatal head growth in very preterm infants is associated with impaired neurodevelopment outcome. Acta Paediatr 102(9): 883-888.

- Power VA, Spittle AJ, Lee KJ, Anderson PJ, Thompson DK, et al. (2019) Nutrition, Growth, Brain Volume, and Neurodevelopment in Very Preterm Children. J Pediatr 215: 50-55e3.

- Tan MJ, Cooke RW (2008) Improving head growth in very preterm infants--a randomised controlled trial I: neonatal outcomes. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 93(5): F337-341.

- Van de Pol C, Allegaert K (2020) Growth patterns and body composition in former extremely low birth weight (ELBW) neonates until adulthood: a systematic review. Eur J Pediatr 179(5): 757-771.

- Johnson MJ, Wootton SA, Leaf AA, Jackson AA (2012) Preterm birth and body composition at term equivalent age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 130(3): e640-649.

- Giannì ML, Roggero P, Piemontese P, Morlacchi L, Bracco B, et al. (2015) Boys who are born preterm show a relative lack of fat-free mass at 5 years of age compared to their peers. Acta Paediatr 104(3): e119-123.

- Roggero P, Giannì ML, Liotto N, Taroni F, Orsi A, et al. (2011) Rapid recovery of fat mass in small for gestational age preterm infants after term. PLoS One 6(1): e14489.

- Kiger JR, Taylor SN, Wagner CL, Finch C, Katikaneni L (2016) Preterm infant body composition cannot be accurately determined by weight and length. J Neonatal Perinatal Med 9(3): 285-290.

- Tonkin EL, Collins CT, Miller J (2014) Protein Intake and Growth in Preterm Infants: A Systematic Review. Glob Pediatr Health 1: 2333794X14554698.

- Walsh V, Brown JVE, Askie LM, Embleton ND, Mc Guire W (2019) Nutrient-enriched formula versus standard formula for preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7: CD004204.

- Hiersch L, Melamed N (2018) Fetal growth velocity and body proportion in the assessment of growth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 218(2S): S700-S711e1.

- Raiten DJ, Steiber AL, Carlson SE, Griffin I, Anderson D, et al. (2016) Working group reports: evaluation of the evidence to support practice guidelines for nutritional care of preterm infants-the Pre-B Project. Am J Clin Nutr 103(2): 648S-678S.

- Lapillonne A, Griffin IJ (2013) Feeding preterm infants today for later metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes. J Pediatr 162(3 Suppl): S7-16.

- Embleton ND, Korada M, Wood CL, Pearce MS, Swamy R, et al. (2016) Catch-up growth and metabolic outcomes in adolescents born preterm. Arch Dis Child 101(11): 1026-1031.

- Bouyssi Kobar M, Du Plessis AJ, Mc Carter R, Brossard Racine M, Murnick J, et al. (2016) Third Trimester Brain Growth in Preterm Infants Compared with In Utero Healthy Fetuses. Pediatrics 138(5): e20161640.

- Harville EW, Buekens PM, Cafferata ML, Gilboa S, Tomasso G, et al. (2020) Measurement error, microcephaly prevalence and implications for Zika: an analysis of Uruguay perinatal data. Arch Dis Child 105(5): 428-432.

Research Article

Research Article