Abstract

Background: Late dumping syndrome is a possible side-effect of gastric bypass. Hypoglycemic symptoms may develop 3-4 hours after certain types of foods. There may exist patients, however, who present hypoglycemia in the absence of dumping syndrome. The presence of only mild symptoms of hypo-glycemia may make the evaluation of these patients difficult and delay the identification of other possible sources of hyperinsulinemia, including an insulinoma.

Case Report: A 37-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) for morbid obesity. After operation, the patient had repeated episodes of hypoglycemia, diagnosed at follow-up as late dumping syndrome. The persistence of hypo-glycemic episodes after nutritional counseling and modifications in the feeding pattern led to consideration of an autonomous source of hyperinsulinemia, and MRI and endoscopic ultrasound identified insulinoma. After a laparoscopy and pancreatic tumor resection, she remains free of symptoms.

Conclusion: Hypoglycemic episodes after obesity surgery are not always related to dumping syndrome. The persistence of hypoglycemia despite nutritional counseling should raise the possibility that there may be other causes of dumping-like symptoms. Insulinoma, the most common cause of endogenous hyperinsulinemia, should be investigated in these patients, since it is a tumor that can be cured.

Keywords: Morbid Obesity, Bariatric Surgery, Gastric Bypass, Dumping Syndrome, Hypoglycemia, Insulinoma.

Introduction

Bariatric surgery is the most efficient treatment for morbid obesity. The combined properties of restrictive and malabsorptive gastric bypass lead to a low incidence of complications and to long-term weight loss [1]. Good results, however, depend on the bariatric surgeon and the multidisciplinary team dealing with the patients before and after surgery [2]. Physicians must be prepared to recognize complications and side-effects related to surgery. Dumping syndrome is a not uncommon complication of gastric bypass. The ingestion of calorie-dense, high-osmotic food followed by rapid emptying into the small intestine causes the release of peptides that induce tachycardia, palpitations, diaphoresis, and nausea [3]. Although these symptoms are considered side-effects of the surgery, their occurrence helps to limit the amount of food ingested, and, therefore, is one of the possible mechanisms for the good results of the gastric bypass. In most cases, the patients learn to avoid dumping syndrome by changes in quantity and quality of food ingested. We report the case of an obese patient who, after LRYGB, had started to experience symptoms of hypoglycemia. The patient was misdiagnosed as dumping syndrome and continued to have symptoms despite the nutritional counseling. Investigation found an insulinoma as the cause of hypoglycemia.

Case Report

37-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our center

because of morbid obesity. She had tried to lose weight several

times, including with medications, but never succeeded. Her

incapacity in adhering to different nutritional approaches

associated with a persistent feeling of hunger became worse

in the past year. Her height was 179cm and body weight 130kg

Body Mass Index (BMI ) = 41 kg / m2 . She underwent an Oral

Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT), which demonstrated deep

hypoglycemia after 90min, she received nutritional counseling returned 3 months later, with further weight gain of 7kg, unable

to follow the prescribed diet. She was then referred to our center

and she passed LRYGB. She lost weight (BMI 25), but 6 years later

she complained of episodes of nausea, tachycardia, and vomiting.

However, she did not associate these with feeding. She was

diagnosed as having late dumping syndrome and was advised to

decrease the ingestion of sweets and high osmolar fluids and to

increase the number of meals per day. The patient continued to have

these symptoms despite all changes in the eating pattern. She was

then referred to an endocrinologist for further investigation. Since

no response was observed after nutritional counseling, biochemical

tests were performed to investigate hyperinsulinemia.

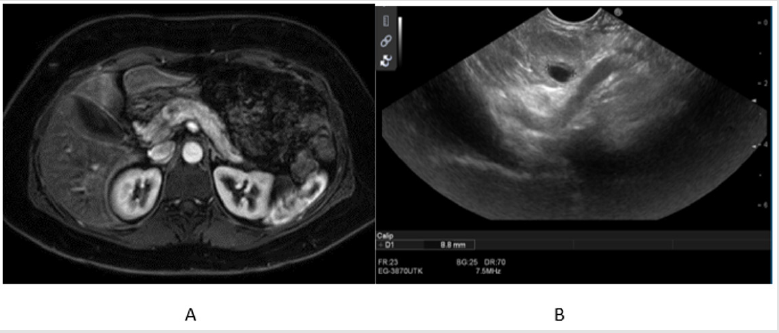

MRI and endoscopic ultrasound were performed, and both

demonstrated the presence of a Well differentiated endocrine

pancreatic neoplasia. (diameter 1.8cm) of approximately 1.8cm in

the body of the pancreas without lympho-vascular or perineural

invasion. (Figures 1A & 1B). A laparoscopy was performed, and an

insulinoma was identified and enucleated. After surgery, there have

been no further hypoglycemic episodes or symptoms.

Figure 1:

a. Magnetic resonance imaging and

b. Endoscopic ultrasound scans of the abdomen showing the presence of an insulinoma in the body of the pancreas.

Discussion

Insulinomas are the most common source of hyper-insulinemic

hypoglycemia [4]. The occurrence of hypoglycemic episodes,

although strongly suggestive of insulinoma, may be underestimated

in some patients, delaying the identification of the disease for up

to 5 years [5]. Even though neuroglycopenic symptoms are the

most known, some patients may present only mild symptoms or

signs, including weight gain in approximately 40% of the patients

[5]. Clinical and biochemical data from our patient suggest that

an insulinoma could have been one of the possible causes for the

weight gain and lack of response to clinical treatment of obesity

before bariatric surgery. The presence of hypoglycemia during

oral glucose tolerance test may indicate that, at that time, the

patient already had an autonomous source of insulin, which was

missed due to the major concern with weight gain and insulin

resistance. Moreover, persistent hyperinsulinemia in morbidly

obese patients is almost always suggestive of insulin resistance.

The elevated insulin levels in these patients are usual. Thus, only a

prolonged fast test would allow a better distinction between insulin

resistance and autonomous hyperinsulinemia. Lack of awareness of

symptoms of hypoglycemia by the patient may also result in delay

in the identification of the insulinoma. These patients often fail to

recognize autonomic warning symptoms. Therefore, hypoglycemia

is only detected through the presence of neuroglycopenic symptoms.

This situation has been described in patients with insulinomas

[6,7] as in a patient after vagotomy and gastric resection for ulcer

recurrence [8].

It has been suggested that this lack of awareness of

hypoglycemia may be due to a generalized central system

adaptation after repeated episodes of hypoglycemia [9,10]. If the

patient did have the insulinoma before surgery, she may have

been suffering episodes for a long time, which may have ultimately

resulted in her unawareness of episodes. Also, the persistent feeling

of hunger reported by the patient as the cause of her inability to

follow the prescribed diets may be an indirect sign of persistent

hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemic symptoms in obese patients after

bariatric surgery are usually related to dumping syndrome. Late

dumping syndrome is characterized by reactive hypoglycemia

secondary to hyperinsulinemia. Symptoms, mainly perspiration,

shakiness, difficulty in concentrating, decreased consciousness,

and hunger [11] occur 2-3 hours after feeding and are related

to glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), gastro-intestinal inhibitory peptide (GIP), and high glucagon levels [12,13]. These symptoms

are expected in the early phases of follow-up after gastric bypass.

Therefore, their occurrence is usually considered normal and no

further investigation is performed. The frequency and severity

of symptoms usually ameliorate with nutritional counseling and

modifications in the feeding pattern.

Some patients who present late dumping syndrome require

medications to control the hypo-glycemia. During the post-surgery

period, our patient received nutritional counseling as an attempt to

control the hypoglycemic episodes. She was advised to reduce the

amount of carbohydrate ingested and to increase the number of tiny

meals. It is interesting to speculate that these recommendations

may have worsened the episodes. Since the desirable effect was not

achieved, the patient was referred to an endocrinologist for further

evaluation. The prompt identification of fasting hypoglycemia

and hyperinsulinemia indicated that there may be an alternative

cause for hypoglycemia instead of late dumping syndrome.

The endoscopic ultrasound and MRI were then performed and

identified the pancreatic tumor as the organic cause of the

hypoglycemia. A laparoscopy was performed, and the insulinoma

was enucleated. It is important to consider that symptoms of

dumping are usually nonspecific, resembling those observed in

hypoglycemic patients. Based on this, nutritional counseling should

always be the first therapeutic intervention for patients with such

symptoms. However, if the symptoms persist, careful investigation

for an autonomous source of insulin should be performed before

beginning pharmacologic therapy for dumping syndrome. Patients

with persistent hypoglycemic episodes should have glucose, insulin

and C-peptide levels determined after a 12-hour fast, to exclude an

autonomous source of insulin secretion. In cases where these tests

are considered still doubtful, the patient should be hospitalized,

and the test should be repeated after a prolonged fast.

Conclusion

Bariatric surgeons should be aware of metabolic conditions including hypoglycemia, as a treatable cause of dumping-like symptoms.

References

- Dayan D, Kuriansky J, Abu Abeid S (2019) Weight Regain Following Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: Etiology and Surgical Treatment. Isr Med Assoc J 12(21): 823-828.

- Giusti V, Suter M, Héraief E, R C Gaillard, P Burckhardt (2001) Rising role of obe-sity surgery caused by increase of morbid obesity, failure of conventional treatments and unrealistic expectation: Trends from 1997 to 2001. Obes Surg 13(5): 693-698.

- Kellum JM, Kuemmerle JF, O’Dorisio TM, P Rayford, D Martin, et al. (1990) Gastrointestinal hormone response to meals before and after gastric bypass and vertical banded gastro-plasty. Ann Surg 211(6): 763-771.

- Matej A, Bujwid H, Wroński J (2016) Glycemic control in patients with insulinoma. Hormones (Athens) 15(4): 489-499.

- Dizon AM, Kowalyk S, Hoogwerf BJ (1999) Neuroglycopenic and other symptoms in patients with insuli-nomas. Am J Med 106: 307-310.

- Krysiak R, Okopień B, Herman ZS (2007) Wyspiak wydzielajacy insuline [Insulinoma]. Pol Merkur Lekarski 22(127): 70-74.

- Brown E, Watkin D, Evans J, Yip V, Cuthbertson DJ (2018) Multidisciplinary management of refractory insulinomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 88(5): 615-624.

- Tóth M, Szücs N, Jakab Z, Doros A, Nemes Z, et al. (2011) Malignus insulinoma [Malignant insulinoma]. Orv Hetil 152(10): 398-402.

- Bellini F, Sammicheli L, Ianni L, C Pupilli, M Serio, et al. (1998) Hypoglycemia unawareness in a patient with dumping syndrome: report of a case. J Endocrinol Invest 21: 463-467.

- Boyle PJ, Kempers SF, OConnor AM, R J Nagy (1995) Brain glu-cose uptake and unawareness of hypoglycemia in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 333(26): 1726-1731.

- Bertolotti A, Borgogna M, Facoetti A, Marsich E, Nano R (2009) The effects of alginate encapsulation on NIT-1 insulinoma cells: viability, growth and insulin secretion. In Vivo 23(6): 929-935.

- Mulla CM, Storino A, Yee EU, Lautz D, Sawnhey MS, et al. (2016) Insulinoma After Bariatric Surgery: Diagnostic Dilemma and Therapeutic Approaches. Obes Surg 26(4): 874-881.

- Tarchouli M, Ali AA, Ratbi MB, Belhamidi Ms, Essarghini M, et al. (2015) Long-standing insulinoma: two case reports and review of the literature. BMC Res Notes 8: 444.

Case Report

Case Report