Abstract

A systematic literature review was conducted on Advanced Care Planning (ACP) to discern the factors which impeded its acceptance among the Singapore population. The key finding of this review is that Singaporeans have greater awareness of ACP, but social and cultural factors continue to hinder its acceptance by the Singapore population. Based on this finding, this study designed a set of vignettes to suss out the values that ACP decision could be based on. The administration of ACP could circumvent culturally sensitive issues by using a third-person perspective in the vignettes. The patient’s preferences could also be more clearly stated in scenarios whereby there are competing interest e.g. the dilemma between personal preferences and burdening the family. This study highlights the importance of an ongoing discourse as the values of patients may change over time. The use of vignettes supplements existing ACP questions, facilitates ongoing ACP conversations, and creates opportunities to provide socio-emotional support for the patient

Keywords:Advance Care Planning; ACP; End-of-life; Palliative; Social-Cultural

Abbreviations: ACP: Advanced Care Planning; AMD: Advanced Medical Directive; MOH: Ministry of Health; AIC: Agency for Integrated Care; ACPEL: Advance Care Planning and End of Life Care; TTSH: Tan Tock Seng Hospital

Introduction

Advanced Care Planning (ACP) refers to a voluntary, non-legally

binding discussion about future care plans between an individual,

his healthcare providers and close family members, in the event

that the individual becomes incapacitated and unable to make

decisions. ACP may also include clarifications about the individual’s

wishes, values, and healthcare objectives. ACP does not only deal

with end-of-life issues, but also applies to long-term care. ACP

also includes the Advanced Medical Directive (AMD) and Lasting

Power of Attorney [1,2]. In 2011 the Ministry of Health (MOH)

Singapore, had appointed the Agency for Integrated Care (AIC) to

coordinate the implementation of a national ACP program across

different healthcare institutions [3]. Over the last few years, MOH

has implemented a series of measures to raise public awareness

of ACP and increase manpower in the palliative healthcare sector,

which have led to a significant increase in the take-up rates for ACP

[3,4]. Despite the increase in the take-up rate of ACP, these studies

[5,6] continued to highlight challenges which impede the initiation

or completion of ACP by the Singapore population; some of these

challenges are similar to those faced by Western societies, but there

are challenges which are unique to Asian cultures.

Systematic reviews across countries highlighted that there

are major knowledge gaps about ACP initiation, timeliness,

optimal content, and impact because of narrow research focus and

fragmented evidence [5,6]. Research should use a holistic evaluative

approach that considers its intricate working mechanisms and the

influence of systems and contexts. Systematic reviews [7,8] on ACP

across countries are available, however one of the issues is the

inconsistencies in the types of instruments and the number of items

used to assess knowledge of ACP. Thereby, this systematic review

has chosen to focus on the Singapore context to understand unique

factors that impeded initiation and conduct of ACP. Even though the

application of ACP should be sensitive to cultural differences, the

proposed dynamic value-based approach to ACP can be universal

in application. The vignettes can be adapted to be context-specific and context-relevant. In the Asian context, discussion on death and

dying may cause the family member to be mistaken as being unfilial

i.e. avoiding the responsibility of caring for the old and aged [9].

The use of indirect communication approaches to determine the

readiness of traditional Chinese seniors was recommended [10,11].

Faith-based values and interpretation of religious doctrines can

influence patients’ views and receptivity towards ACP [12].

In fact, it is suggested that religious leaders and even social

workers and might be suitable candidates in influencing the views

and receptivity of ACP [13,14]. There are challenges that impede

the initiation of ACP discussions including physicians’ apathy and

inadequacy of training. Thus far there has been no systematic review

about the ACP in Singapore, so our study seeks to review existing

literature to discern the factors which impeded its acceptance

among the Singapore population. More importantly, our study

aimed to utilize the findings from this systematic literature review

to design a dynamic principal-based approach to complement

existing ACP questions. The objective of value-based approach

is to overcome existing hindrances to the implementation and

acceptance of ACP. Another objective of this approach is to allow

patients and their family members to base end-of-life decisions on

values instead of narrowly defined preferences for specific matters.

This approach is also dynamic as it considers competing interests

and dilemmas, to allow patients to prioritize their preferences. As

existing ACP may not capture nuances and may not be sufficiently

versatile in decision making when confronted with “shades of grey”

[15-21], a value-based approach will also assist family members to

make more informed decisions when faced with dilemmas or grey

areas.

Method

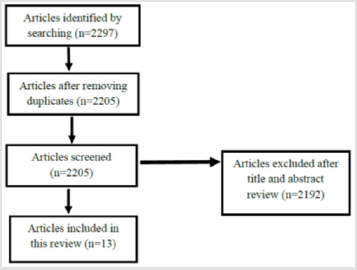

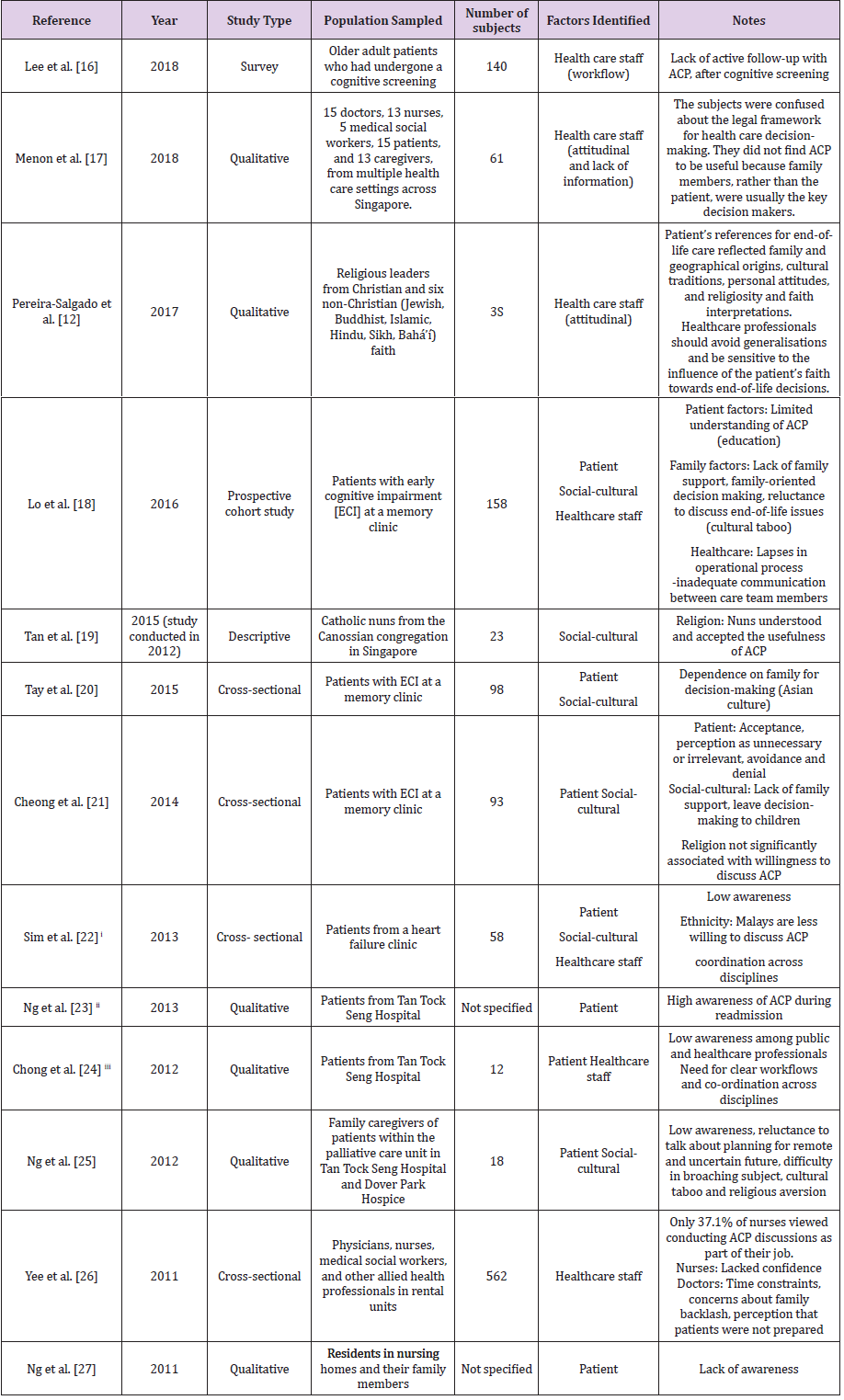

An electronic search of the following databases: PsycINFO, PubMed, CINAHL, Google Scholar, SAGE Journals and Singapore Medical Journal, was carried out. We searched for research articles up till Sep 2020 and used the Boolean search criteria: (“advance care planning” OR “advanced care planning”) AND “Singapore”. We included all study types in English which were carried out on the Singapore population (Figure1). In addition to the published studies, we also reviewed findings which were presented in posters and conferences so as to prevent publication bias (Table 1).

Findings

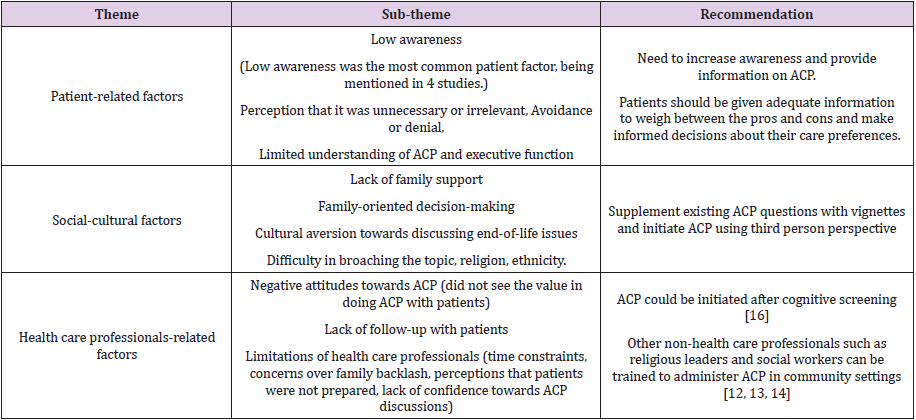

The search criteria above yielded a total of 2297 articles. After removing duplicates, based on title, abstract and article review, we short-listed 13 articles for inclusion. The studies that we identified were mainly qualitative studies. Three of them were cross-sectional, one was on prospective cohort, and the remaining nine were descriptive in nature. 10 of the studies were published in journals, while the other three studies were from Advance Care Planning and End of Life Care (ACPEL) conference oral and poster presentations. our study had categorized the challenges broadly into patient-related factors, social-cultural factors, and health care professional-related factors (Table 2).

Discussion

Although low awareness among the patients was the most

frequently highlighted challenge overall, it appeared that this factor

was a major challenge mostly in the earlier years up till 2013. The

four reports which listed low awareness as a challenge were from

2013 and earlier [22-25]. Reports after 2013 did not highlight this

as a challenge. Indeed, a study by Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH)

presented in 2013 had already reported that there was a high

awareness of ACP during readmission [23]. It could be that lack of

awareness no longer showed up as a significant factor in the latter

studies, or that researchers concentrated on other factors which

were more salient since then. This trend suggested that the efforts

by government and health care institutions to promote public

awareness of ACP had been successful. On the other hand, the next

two commonly cited patient factors – education and perception

that ACP was unnecessary, were present even in the latest study

published in 2016. However, the studies that mentioned these

two factors were all conducted on patients with ECI, so we need

to exercise caution before generalizing this to the wider patient

population [18,20,21]. At present, it seemed that social-cultural

factors revolving around the family remain the biggest challenges

to take-up of ACP locally. In the Asian cultural context, family

involvement as a major challenge for ACP has previously been

reported in studies on other Asian populations [26-29].

In Singapore, the Asian emphasis on collective decision-making

leads to the propensity by patients to leave decision-making about

end-of-life issues to their children, and was cited in three studies [18,

20, 21]. According to the study by Tay (2015) [20] issues pertaining

to the Asian culture of collective family decision-making were the

greatest barriers to ACP engagement. Lo’s (2016) [18] study on

patients with ECI showed that the unmarried patients were more

likely to actualize ACP plans compared to married patients; it was

likely the latter would tend to defer decision-making on end-oflife

issues to family members. Another major Asian cultural factor

was the aversion towards talking about death for fear that it would

bring bad luck, mentioned in two reports [18, 23]. Lack of family

support for ACP was another social-cultural factor. Cheong et.al

[21] categorized this lack of support into the following: patient’s

lack of trust in the family, family agreeing with patient that ACP

was irrelevant, and family members’ dismissive attitude towards

patients’ end-of-life plans [21].

However the effect of religion and ethnicity on the Singapore

population is unclear. In a focus group discussion by Tan et.al

(2017) [19] with 23 Catholic nuns, 18 of the nuns (78%) responded

that ACP was not against their religious beliefs. In the descriptive

study by Ng (2013) [13], one participant expressed an objection

towards ACP on the basis of her Catholic belief [23]. Viewing

these two studies together, it might be reasonable to conclude

that while the religious leaders are not against the concept of ACP,

it is unclear whether this opinion is shared by the rank-and-file

religious followers. A third study had ambivalent outcome with

regard to religion; although the theme of leaving the future to

God cropped up, the study did not find any significant association

between religion and willingness to engage in ACP discussion [21].

Ethnicity was mentioned as a challenge in a pilot study conducted

on Singapore patients from a heart failure clinic [22]. This study showed that Malays were less likely to discuss ACP compared to

other ethnic groups. We can compare this finding against that from

an earlier Malaysian study which revealed that race, ethnicity, and

cultural values were important factors in ACP. The majority of the

Malaysian subjects, especially those with Islamic faith, believed

that their views were influenced by religion [30]. For the Singapore

population, while the results thus far appear mixed, it is reasonable

to conclude that views towards ACP might be split along religious

and ethnic lines. More local research is needed to shed light into

this.

Another major aspect of challenges to ACP is the lapse in communications and co-ordination among health care members, and this is a problem that has remained persistent. A study in 2016 revealed that lapses in operational processes mainly due to inadequate communication within the team played a significant role in low ACP completion [18]. Two other earlier studies also identified inadequate coordination across multiple disciplines as a major challenge [22,24]. In addition, health care workers’ individual competencies were flagged out as a major challenge in the early years. A 2011 study on the knowledge, attitudes and experience of renal health care providers towards ACP showed that only 37.1% of nurses considered ACP discussion as part of their role, and that nurses were the least confident in conducting ACP discussions [26]. Doctors fared better, but still, the study identified several barriers faced by physicians – fear of upsetting the family, lack of time, and the perception that patients were not ready to discuss ACP. Since 2011, the AIC has been training health care personnel in ACP facilitation skills [3,31] and it is likely that health care personnel are now better equipped to facilitate ACP discussions, although there is no recent study to assess the current state of competency.

The Dynamic Value-based Approach to Advance Care Planning

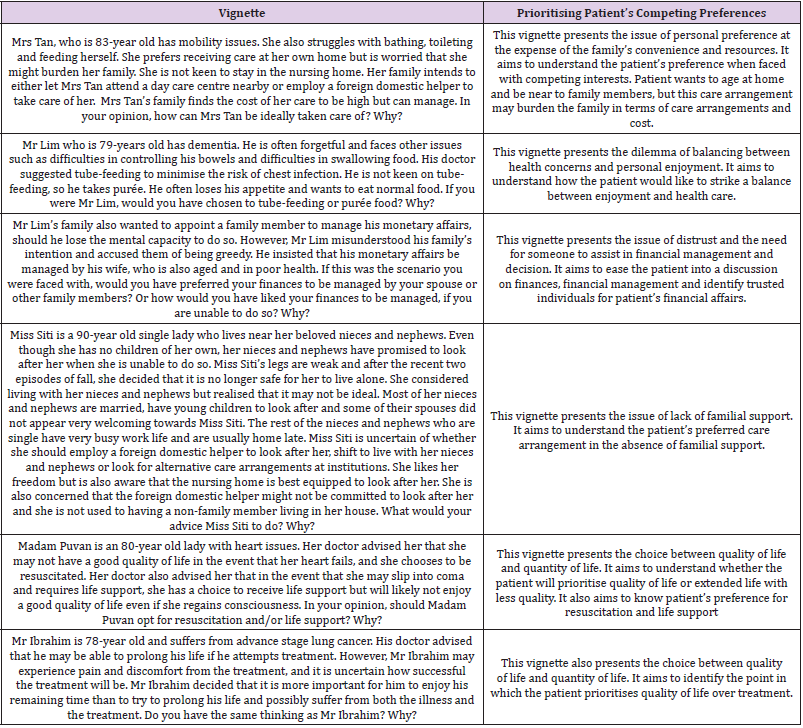

Following the findings from this literature review, this study proposed the use of vignettes to elucidate values and principles of the patient, in addition to existing ACP methods. Vignettes are “short stories about hypothetical characters in specified circumstances, to which the interviewee is invited to respond” [32]. The use of fictitious but popular scenarios that are culturally adapted provides realism that enables the patient to relate to, and suss out their values and principles behind their expressed preferences. The use of third person perspective also allows family members and professionals to circumvent the issue of broaching sensitive topics. For instance, traditional Chinese seniors may find it inauspicious to talk about death and dying. Using vignettes will enhance the ability for realism and more accurately reflecting patient’s preferences in scenarios that present dilemmas and limitations to the implementation of their preferred care and medical arrangements. This study has drafted the vignettes in (Table 3). as samples for adaptation and application, to overcome social-cultural barriers in initiating ACP.

Limitations

The biggest drawbacks to the studies used in this review were the small sample sizes and the limitation of the sampled populations to specific types of patients, which makes it hard to generalize the findings. Only two studies had n>100 (Yee, 2011) [5]. Most of the other studies were conducted on specific types of patients (patients from a memory clinic in the case of Lo, Tay, and Cheong [18,20,21] the palliative care unit for Ng’s [25] study, health professionals in rental units for Yee [13], heart failure clinic for Sim (2013) [33]. In fact, three of the studies – almost one-third of studies in this review – used patients with ECI [18,20,21], so this population segment might be overrepresented in our review. All the 13 studies cited were largely qualitative studies; only four of them carried out further quantitative analysis to discern associations between the variables and ACP take-up [18,20,21,26].

Recommendations

This study recommends for a large-scale mixed research study across various health care and non-health care settings to evaluate the relevance and usefulness of the value-based approach in complementing existing ACP questions. Areas to evaluate would be the cultural fit between the scenarios and issues presented in the vignettes and the Singapore population, the ease of conducting ACP with vignettes, the extent of usefulness in complementing existing ACP questions with vignettes, the impact of findings from vignettes in assisting the patients’ family members in making decisions when faced with ambiguity or dilemmas, the ease and challenges in using vignettes and areas to improve. The reliability of the vignettes could also be evaluated in future studies by applying different vignettes that test for similar values, to assess if the patient’s values are consistent. The validity of the vignettes approach could be strengthened with repetitive usage of different characters and scenarios on the same patient so as to identify and understand changes in values over time.

Conclusion

The government’s public education efforts appeared to have

increased awareness of ACP issues among the public. Currently,

social-cultural factors such as the involvement of the family in the

decision-making process, cultural aversion towards talking about

death, and lack of family support, appear to be the most significant

factors which impeded the take-up of ACP. The use of vignettes is

believed to circumvent the issue of cultural sensitivities by using

fictitious characters and conversing with the patient using a thirdperson

perspective. It is crucial that the administration of ACP

and the vignettes is supported by giving adequate information

for patients and caregivers to weigh between the advantages and

disadvantages of the various options. For instance, the concepts

of “qualitative medical futility” and “quantitative medical futility”

are underlying key values in treatment preferences. Patients need

to understand these concepts and make informed ACP decisions

towards topics such as “preference for” and “when to” withhold

and/or withdraw treatment, be placed on life-support, activate the

do-not-resuscitate order and euthanasia [33].

The administration of ACP should not be a one-off affair. The

dynamic value-based approach encourages ongoing discourse on

ACP, as patient’s values may change over time and as the health

conditions deteriorates. Revisiting the preferences that patients

have earlier indicated will also offer them opportunities to reflect

and be more certain of their preferences. An ongoing discourse

may also lead to deeper discussion and open up opportunities for

emotional support to the patient. The vignettes are believed to

facilitate ACP conversations and surface patient’s concerns and

fears. Patients are then encouraged to indicate preferences that are

more reflective and valid, especially when preferences conflict or

when family members are faced with dilemmas.

References

- (2010) NMEC, Guide for Healthcare Professionals on The Ethical Handling of Communication in Advance Care Planning.

- Tay M, SE Chia, J Sng (2010) Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the Advance Medical irective in a residential estate in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 39(6): 424-428.

- Koh SF (2015) As population ages, more are confronting the last taboo.

- (2015) MOH, End-of-life issues (MOH Parliamentary Q&A).

- Jimenez G, Tan WS, Virk AK, Low CK, Car J, et al. (2018) Overview of Systematic Reviews of Advance Care Planning: Summary of Evidence and Global Lessons. J Pain Symptom Manage 56(3): 436-459.e25.

- Jimenez G, Tan WS, Virk AK, Low CK, Car J, et al. (2018) State of advance care planning research: A descriptive overview of systematic reviews. Palliat Support Care p. 1-11.

- Fahner JC, Beunders AJM, van der Heide A, Judith A C Rietjens, Maaike M Vanderschuren, et al. (2019) Interventions Guiding Advance Care Planning Conversations: A Systematic Review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 20(3): 227-248.

- Kermel Schiffman I, Werner P (2017) Knowledge regarding advance care planning: A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 73: 133-142.

- Cheng HWB (2018) Advance Care Planning in Chinese Seniors: Cultural Perspectives. J Palliat Care 33(4): 242-246.

- Mc Dermott E, Selman LE (2018) Cultural Factors Influencing Advance Care Planning in Progressive, Incurable Disease: A Systematic Review with Narrative Synthesis. J Pain Symptom Manage 56(4): 613-636.

- Ohr S, Jeong S, Saul P (2017) Cultural and religious beliefs and values, and their impact on preferences for end-of-life care among four ethnic groups of community-dwelling older persons. J Clin Nurs 26(11-12): 1681-1689.

- Pereira Salgado A, Mader P, O'Callaghan C, Boyd L, Staples M (2017) Religious leaders' perceptions of advance care planning: A secondary analysis of interviews with Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Islamic, Jewish, Sikh and Bahá'í leaders. BMC Palliat Care 16(1): 79.

- Chu D, Yen YF, Hu HY, Yun Ju Lai, Wen Jung Sun, et al. (2018) Factors associated with advance directives completion among patients with advance care planning communication in Taipei, Taiwan. PLoS One 13(7): e0197552.

- Wang CW, Chan CLW, Chow AYM (2017) Social workers' involvement in advance care planning: A systematic narrative review. BMC Palliat Care 17(1): 5.

- Michael N, O'Callaghan C, Sayers E (2017) Managing 'shades of grey': A focus group study exploring community-dwellers' views on advance care planning in older people. BMC Palliat Care 16(1): 2.

- Lee JJY, Barlas J, Thompson CL, Dong YH (2018) Caregivers' Experience of Decision-Making regarding Diagnostic Assessment following Cognitive Screening of Older Adults. Journal of Aging Research pp. 8352816.

- Menon S, Kars MC, Malhotra C, Campbell AV, van Delden JJM (2018) Advance Care Planning in a Multicultural Family Centric Community: A Qualitative Study of Health Care Professionals', Patients', and Caregivers' Perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage 56(2): 213-221.e4.

- Lo TJ, Ha NH, Ng CJ, Tan G, Koh HM, et al. (2017) Unmarried patients with early cognitive impairment are more likely than their married counterparts to complete advance care plans. Int Psychogeriatr 29(3): 509-516.

- Tan L, Sim LK, Ng L, Toh HJ, Low JA (2017) Advance Care Planning: The Attitudes and Views of a Group of Catholic Nuns in Singapore. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine® 34(1): 26-33.

- Tay SY (2015) Education and Executive Function Mediate Engagement in Advance Care Planning in Early Cognitive Impairment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 16(11): 957-962.

- Cheong K, Fisher P, Goh J, Ng L, Koh HM, et al. (2015) Advance care planning in people with early cognitive impairment. BMJ Support Palliat Care 5(1): 63-69.

- Sim DK (2013) Advance Care Planning for Patients with Heart Failure in a Multi-ethnic South East Asian Cohort. BMJ supportive & palliative care 3(2): 257-258.

- Ng R, Chan S, Ng TW, Chiam AL, Lim (2013) Starting Pilots in Advance Care Planning in a Tertiary Hospital in Singapore. BMJ Support Palliat Care 3(2): 279-279.

- Chong R (2012) Sowing seeds and building collaborations: Challenges faced and learning points in starting systematic advance care planning in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. BMJ supportive & palliative care 2(2): 201-202.

- Ng R, Chan S, Ng TW, Chiam AL, Lim S (2013) An exploratory study of the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of advance care planning in family caregivers of patients with advanced illness in Singapore. BMJ Support Palliat Care 3(3): 343-348.

- Yee A, Seow YY, Tan SH, Goh C, Qu L, et al. (2011) What do renal health-care professionals in Singapore think of advance care planning for patients with end-stage renal disease? Nephrology (Carlton) 16(2): 232-238.

- Wee NT, SC Weng, LLE Huat (2011) Advance care planning with residents in nursing homes in Singapore. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development 21(1): 97-104.

- Kwak J, Salmon JR (2007) Attitudes and preferences of Korean American older adults and caregivers on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 55(11): 1867-1872.

- Bowman KW, Singer PA (2001) Chinese seniors' perspectives on end-of-life decisions. Soc Sci Med 53(4): 455-464.

- Htut Y, Shahrul K, Poi PJ (2007) The views of older Malaysians on advanced directive and advanced care planning: A qualitative study. Asia Pac J Public Health 19(3): 58-67.

- Chung I (2013) Implementing a national advance care planning (ACP) program in Singapore. BMJ supportive & palliative care 3(2): 256-257.

- Finch J (1987) The Vignette Technique in Survey Research. Sociology 21(1): 105-114.

- Low JA, Ho E (2017) Managing Ethical Dilemmas in End-Stage Neurodegenerative Diseases. Geriatrics (Basel) 2(1): 8.

Review Article

Review Article