Abstract

Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs) are the leading causes of deaths worldwide. The causes of CVDs are attributed to several factors including genetics, epigenetics, immunology, and lifestyle. CVDs are found to be a major comorbidity for patients inflicted with the ongoing novel coronavirus disease (COVID- 19) caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. However, the underlying mechanisms leading to increased risk of mortality of COVID-19 patients with CVDs is unknown. Recent studies indicate that the mechanisms could partly be explained by the cardiac-related roles of ACE2, which is the host cell’s receptor for SARS-CoV-2. In this mini-review, current findings on the links between COVID-19 and CVDs are discussed, with a focus on ACE2.

Keywords: Cardiovascular Diseases; Genetics; Epigenetics; Immunology; Lifestyle; Pandemic; Clinical Manifestations; Hospitalization; Aerosols; Angiotensin

Abbreviations:CVDs: Cardiovascular Diseases; COVID- 19: Coronavirus Disease; CFR: Case Fatality Rate; ACE: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme; RAS: Renin- Angiotensin System; ACEI: ACE Inhibitors; ARBs: Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

Introduction

The double-menace of COVID-19 and CVDs

For many years, CVDs remain the most common types of noncommunicable

diseases and also the leading causes of deaths

globally [1,2]. However, the current COVID-19 pandemic, which

began in December 2019, has significantly changed the dynamics of

the causes of global mortality due to CVDs. According to the World

Health Organization, the Case Fatality Rate (CFR) of the disease

varies between countries and can be as low as 0.1 % to as high as

over 25% (WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mortality-2020.1). However,

as with other infectious diseases and an ongoing pandemic, the

actual magnitude of the CFR and its cause- effect relationship on

global mortality is yet to be fully comprehended.

Although predominantly a respiratory virus, SARS- Cov-2

is different from its counterparts in its ability to affect multiple

organs and cause a wide range of clinical manifestations [3].

While the majority patients present with mild symptoms (~

81%), a notable percentage of patients have severe (~ 14%) and

even critical manifestations (~ 5%), including respiratory failure,

septic shock and/ or multiple organ failure [3]. Cardiac injury is

observed in a quarter of the patients with COVID-19 [4], with a

range of cardiovascular complications including myocardial injury,

myocarditis, cardiac arrhythmia, ischemic heart disease, cardiac

arrest, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, cardiogenic and mixed shock

[5,6]. Interestingly, although about 25% of the infected patients

have co-morbidities, 60- 90% of the infected patients requiring

hospitalization have pre-existing co-morbidities including CVDs

(21- 28 %) [3]. These patients tend to be older and have worse

composite outcomes compared to younger patients, including

mechanical ventilation, ICU admission and death [6]. Therefore,

although sufficient data correlates existing co-morbidities including

CVDs to COVID- 19, the converse information of CDVs resulting

solely from COVID- 19 is often difficult to estimate [5]. However, the

molecular pathogenesis of COVID- 19 has the potential to shed light

on the cyclic relationship between COVID- 19 and CVDs.

COVID-19 and ACE2

SARS-Cov-2 is transmitted between humans through various means including droplets, aerosols and fomites [7]. Viral infection is initiated by the binding of viral spike (S) proteins with the transmembrane angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). ACE2 is present on the surface of alveolar epithelial cells, macrophages and other cell types including pericytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, macrophages and cardiomyocytes in the cardiovascular system [6,8,9]. ACE2 is a homologue of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), a component of the renin- angiotensin system (RAS), which is important in vital physiological functions not limited to maintenance of blood volume, systemic vascular resistance, and inflammatory response in vascular cells [10,11]. S protein is subsequently cleaved by the transmembrane serine protease TMPRSS2, enabling fusion of the viral membrane with that of the host cell and consequently, entry of the virus into the cytoplasm. As epithelial tissues in the respiratory tract express both ACE2 and TMPRSS2, this is considered the primary mode of COVID-19 infection in humans [8].

CVDs, COVID-19, and ACE2

Expression of ACE2 is upregulated in failing hearts [6].

Conversely, two classes of RAAS (Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone

system) inhibitory drugs, namely ACE inhibitors (ACEI) and

angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), commonly used to treat

CVDs, result in the increase of ACE2 [12]. Intriguingly, ACE2 levels

continue to vary during different stages of COVID-19 infection

and the prognosis of cardiac pathologies. Hence, a well-rounded

analysis of RAAS-associated factors during different stages of SARSCoV-

2 infection, and correlation with medications, are needed

for developing RAAS-targeted anti-COVID-19 therapies [13]. A

recent study involving state-of-art cardiac single cell atlas of adult

humans demonstrated a link between COVID-19 and the elevated

expression of ACE2 in pericytes, which are cells of the basement

membrane that encompass the endothelial cells of capillaries and

venules [14].

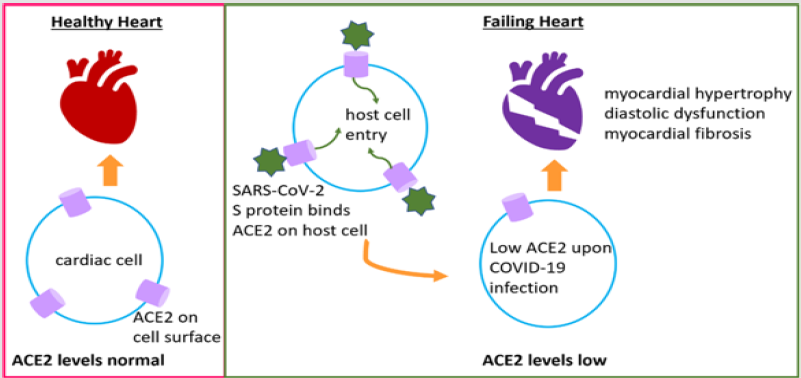

The study proposes that SARS-CoV-2 likely targets pericytes

due to ACE2 overexpression on their surface, leading to the damage

of pericytes during viral infection, which snowballs into dysfunction

of capillary endothelial cells and microvasculature. Interestingly,

although elevated levels of ACE2 on the cell surface may facilitate

SARS-CoV-2 entry into the host cells, it has been observed that ACE2

levels are low in hearts of mice and autopsied humans, after SARSCoV-

2 infection [15]. It is intriguing how SARS-CoV-2 utilizes ACE2

to enter the host cell, and then COVID-19 infection results in reduced

expression of ACE2, through some undiscovered mechanism.

Reduced ACE2 is detrimental for the heart because normal levels

of ACE2 prevent heart failure, myocardial hypertrophy, diastolic

dysfunction, and myocardial fibrosis [16], and it is expressed in

cardiac cells like cardiomyocytes, cardiac fibroblasts, and coronary

endothelial cells [17]. Hence, ACE2 plays counter-acting roles by

harming the host through its viral receptor activity and benefiting

the host’s cardiac physiology (Figure 1). As a result, therapeutic

interventions to manipulate ACE2 levels through RAS inhibition

continue to be debatable [18].

Figure 1: COVID-19 exacerbates CVDs. ACE2 maintains normal cardiac function and health, and it is expressed on cardiac cells like cardiomyocytes, cardiac fibroblasts, pericytes, and coronary endothelial cells. During SARS-CoV-2 infection, the virus enters host cell through ACE2 receptor on the cell surface. Following infection, ACE2 levels reduce leading to diastolic dysfunction, myocardial dysfunction and fibrosis, and heart failure.

Conclusion

The above observations may contribute to the understanding of why COVID-19 disproportionately infects specific populations, like aged patients, under treatment of underlying comorbidities including CVDs, thereby making them significantly more susceptible to adverse composite outcomes and mortality [19]. Considering the opposite scenario, systemic inflammation and metabolic deregulation are associated with most viral infections, although the magnitude in COVID- 19 is several folds higher [20]. Both phenomena are notable forerunners in cardiovascular complications [21,22]. Additionally, COVID- 19 also results in several other types of cardiovascular complications previously listed [5,6]. The relationship between COVID- 19 and CVDs is thus bidirectional and presents a challenge for patients and health care professionals alike. Hence, a deeper understanding of the links between the regulation of ACE2 in the context of COVID-19 and CVDs will enable the development of targeted therapeutics against both diseases.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- (2019) Group WCRCW: World Health Organization cardiovascular disease risk charts: revised models to estimate risk in 21 global regions. Lancet Glob Health 7(10): e1332-e1345.

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, et al. (2020) Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2020 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 141(9): e139-e596.

- Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC (2020) Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review JAMA.

- Calvillo Arguelles O, Ross HJ (2020) Cardiac considerations in patients with COVID-19. CMAJ 192(23): E630.

- Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, Chuich T, Laracy J, et al. (2020) Cardiovascular Considerations for Patients, Health Care Workers, and Health Systems During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 75(18): 2352-2371.

- Guzik TJ, Mohiddin SA, Dimarco A, Patel V, Savvatis K, et al. (2020) COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system: implications for risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options. Cardiovasc Res 116(10): 1666-1687.

- Jayaweera M, Perera H, Gunawardana B, Manatunge J (2020) Transmission of COVID-19 virus by droplets and aerosols: A critical review on the unresolved dichotomy. Environ Res 188: 109819.

- Nishiga M, Wang DW, Han Y, Lewis DB, Wu JC (2020) COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease: from basic mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Nat Rev Cardiol 17(9): 543-558.

- Tucker NR, Chaffin M, Bedi KC, Papangeli I, Akkad AD, et al. (2020) Myocyte-Specific Upregulation of ACE2 in Cardiovascular Disease: Implications for SARS-CoV-2-Mediated Myocarditis. Circulation 142(7): 708-710.

- Ruiz Ortega M, Lorenzo O, Ruperez M, Esteban V, Suzuki Y, et al. (2001) Role of the renin-angiotensin system in vascular diseases: expanding the field. Hypertension 38(6): 1382-1387.

- Fountain JH, Lappin SL (2020) Physiology, Renin Angiotensin System. In StatPearls. edn. Treasure Island (FL).

- Ma TK, Kam KK, Yan BP, Lam YY (2010) Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade for cardiovascular diseases: current status. Br J Pharmacol 160(6): 1273-1292.

- South AM, Diz DI, Chappell MC (2020) COVID-19, ACE2, and the cardiovascular consequences. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 318(5): H1084-H1090.

- Chen L, Li X, Chen M, Feng Y, Xiong C (2020) The ACE2 expression in human heart indicates new potential mechanism of heart injury among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Cardiovasc Res 116(6): 1097-1100.

- Oudit GY, Kassiri Z, Jiang C, Liu PP, Poutanen SM, et al. (2009) SARS-coronavirus modulation of myocardial ACE2 expression and inflammation in patients with SARS. Eur J Clin Invest 39(7): 618-625.

- Santos RAS, Sampaio WO, Alzamora AC, Motta Santos D, Alenina N, et al. (2018) The ACE2/Angiotensin-(1-7)/MAS Axis of the Renin-Angiotensin System: Focus on Angiotensin-(1-7). Physiol Rev 98(1): 505-553.

- Guo J, Huang Z, Lin L, Lv J (2020) Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Cardiovascular Disease: A Viewpoint on the Potential Influence of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors/Angiotensin Receptor Blockers on Onset and Severity of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection. J Am Heart Assoc 9(7): e016219.

- Lumbers ER, Delforce SJ, Pringle KG, Smith GR (2020) The Lung, the Heart, the Novel Coronavirus, and the Renin-Angiotensin System; The Need for Clinical Trials. Front Med (Lausanne) 7: 248.

- Bonow RO, Fonarow GC, O'Gara PT, Yancy CW (2020) Association of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) With Myocardial Injury and Mortality. JAMA Cardiol.

- Mery G, Epaulard O, Borel AL, Toussaint B, Le Gouellec A (2020) COVID-19: Underlying Adipokine Storm and Angiotensin 1-7 Umbrella. Front Immunol 11: 1714.

- Ormazabal V, Nair S, Elfeky O, Aguayo C, Salomon C (2018) Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol 17(1): 122.

- Taube A, Schlich R, Sell H, Eckardt K, Eckel J (2012) Inflammation and metabolic dysfunction: link to cardiovascular diseases. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302(11): H2148-2165.

Mini Review

Mini Review