Abstract

Recent research showed that the disengagement of a child and family from an inpatient

rehabilitation program to the home environment, can lead to a deterioration of the

achieved improvements over time. In order to fathom why this occurs this study focused

on the challenges parents face once their child returns home from an inpatient Functional

Intensive Therapy program. A qualitative study was conducted (semi-structured indepth

interviews) with parent couples (n=16) who’s child participated in an intensive

inpatient rehabilitation program. The data collected from the interviews were analyzed

with directed content analysis.

The parents articulated challenges and needs once their child returned home:

1) Restricted knowledge about the child’s disability,

2) Coping with stress,

3) Empowering behavior regarding independent capabilities and

4) Parent roles and interactions between parents.

Out of these challenges and needs several possibilities emerged for this functional

intensive inpatient program that could prevent relapses in the long term: provide psychoeducation

on disability from physical, cognitive and social emotional perspective, and

increase capacities of parents to deal with stress or unburden parents by outsourcing

stressful tasks, guide parents with emotional challenges and feelings of loss regarding

the possibilities of their disabled child, help parents identify their pedagogic values and

finally adapt one unified approach for more clarity for the child.

Keywords: Inpatient Functional Intensive Rehabilitation; Transition Care; Adolescent; Family-Oriented Rehabilitation

Introduction

Reaching the highest form of independency and increasing

independent capabilities is the most important goal regarding

the rehabilitation of children with physical disabilities. This is

important because it affects the quality of life of children with

a disability [1]. To reach this independency potential, a short

intensive rehabilitation program seems to be more beneficial and effective compared to the regular long term care [1-3]. Evidence

shows that significant short term results can be achieved, due to

high intensive therapy [3,4]. For example: gross motor abilities,

walking endurance, and upper-extremity abilities improved and

remained improved after three months follow-up. Short intensive

therapy is often provided during inpatient rehabilitation programs.

‘FITcare4U’ is an example of an functional intensive inpatient

rehabilitation program and will be used for this research. FIT

stands for ‘Functional Intensive Therapy. FITcare4U is based on the

principles of the Hand-Arm Bimanual Intensive Therapy Including

Lower Extremities (HABIT-ILE) in Cerebral Palsy and translated to

the Dutch rehabilitation situation for adolescents with all kind of

motor disabilities and focus on mobility and self-care [4].

The main goal of FITcare4U is to empower adolescents with a

disability in a very intensive and short treatment period, to reach

their maximum potential concerning independency in a more

effective manner [4]. Whether the main goal of an inpatient program

is physical or mental improvement, positive short term effects are

found in several studies. For example, when comparing inpatient

rehabilitation programs with inpatient programs in which the

population consists of adolescents with diagnosis in the psychiatry

spectrum, recent research also shows positive short term(within 2

months) effects (aged 13 -18 years) [5]. In addition, a short intensive

program for adolescents with a wide array of mental health

diagnosis by Hepper and colleagues (2005) also showed benefits

in the development of coping strategies, sense of own agency and

positive experiences in containment in a controlled environment

[6]. Even though the effects in these short intensive programs are

positive, recent research shows that achieved improvements may

deteriorate over a longer time period especially when returning to

the same environment as before the intervention [7,8].

It seems that once children/adolescents return home, the risk

exists that it is difficult for them to continue the newly acquired

knowledge and skills. This could have implications in terms of

their subsequent development , for example their self-esteem and

self-image [9]. It is possible that the high level of support during

inpatient programs make the transition back home challenging,

given that the same resources: time, pedagogic knowledge and

therapeutic understanding are not typically available in the home

environment [5]. It seems that parents are not fully equipped to

facilitate and empower the children with regards to their new skills

and possibilities. It also seems that the inpatient programs focus

primarily on the adolescent in their treatment while opportunities

arise regarding a systemic cognitive guidance program for parents.

To adapt to the newly learned skills in the home environment, a

healthy family stress level is needed, in order to have enough space

mentally to react adequately as parents [10].

This stress is the accumulation of aspects in several domains,

for example: care tasks, work, social life, family matters. To our

knowledge, it is still unknown what the perspective of parents is

with regard to the experienced stress once adolescents return home

following discharge and how many support parents receive. The

purpose of this study was first to explore the parents’ perspective

on challenges and needs when their child returns home after an

inpatient rehabilitation program. Second to gain insight in the

needs of parents to maintain the positive results of the program

in the long term. Understanding these challenges and needs is a

vital step in the guidance of families during and after an inpatient

rehabilitation program, which may lead to less deterioration of the

learned skills over time.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Semi structured interviews were performed to explore the challenges and needs of parents, regarding their child’s transition from FitCare4U inpatient program to home, in a subjective nonquantifiable way [11].

Setting and Participants

Parents of adolescents who participated in the inpatient program FitCare4U at Adelante rehabilitation centre were asked for consent to use the interviews for this study. The adolescents enrolled in the inpatient FitCare4U program if they had specific goals regarding the development of independent capabilities. Both parents and caretakers (when possible) participated in a parent program as part of their child’s treatment. The parents of the participating adolescents were eligible to participate in the study if:

(1) The adolescents lived with their parents/caretakers,

(2) The adolescents were between eleven and nineteen years

old,

(3) Parents could understand the Dutch language fluently,

and

(4) Attended both parent meetings

Furthermore, there were no physical restrictions regarding

participation.

The Program

FITcare4u is a short functional intensive inpatient program

that aims to empower children and adolescents with a disability,

to reach their maximal potential in independent capabilities and

stimulates the development of self-efficacy due to experiences of

success [4]. It is used to provide a boost in mastering independent

capabilities, developing confidence and self-efficacy. The inpatient

program lasted 15 days, weekends included, with a daily 6-hour

long therapeutic program, combined with school in the morning and

program in afternoon and evening. Each day the specific individual

goals of the children were practiced for 90 min and the remaining

time was spend on performing daily life activities, sports, outdoor

and creative activities. The children were individually coached

by members of a multidisciplinary team of pediatric physical and occupational therapists, sport teachers, nurses, social workers,

psychologists and physicians.

During two parent meetings prior to the program, parents were

informed about the inpatient program for the children, the parent

weekends and the ability to join this study. In the program two full

days, so called ‘parent weekends’ were embedded in which parents

of the adolescents participate in the program. These days were

planned in the second weekend of the program and on the last day

of the program. During these days parents met each other and had

the possibility to share experiences with each other. Furthermore,

parents received information on physical possibilities and

limitations of their child and what they can expect regarding the

future. As the parents are co-partners of their child, they participated

together with their child in several activities in the parent weekend

to experience the gained independent capabilities and self-efficacy

of their child and to get insight on what their child is capable of.

Lastly parents received many practical tips and advices during

parent-meetings on how to retain the progress their children made

during the program and what to do when the adolescent returns

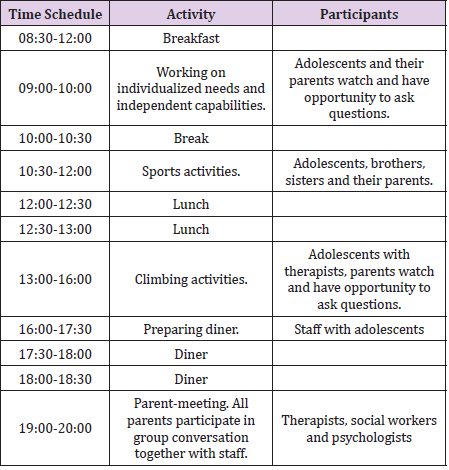

home. Table 1 gives an impression of a parent day: (Table 1).

During the program children worked on their needs and individualized independent capabilities such as increasing their maximum walking distance to better transfer in their home environment (house/school), help parents set the table and clean up afterwards, picking the clothes they want to wear and getting dressed, brushing their teeth and learn how to do their own bowel irrigation or bladder catheterization. Evaluation of the results (for example: gross motor abilities, walking endurance and upperextremity upperextremity abilities) was performed at the end of the program and 3 month after the program.

Procedure

Intervention and assessments were part of the regular functional intensive treatment program in Adelante Centre of Pediatric Rehabilitation in the Netherlands. All parents were informed about the aim of study and the interview procedure before the start of the inpatient program and approved their participation regarding the interviews. If possible, both parents participated in the interviews and no preparation was needed before the interviews. After prior to the interviews. All data was anonymized and documented. The interviews were conducted during the ‘parent weekends’ in the last weekend of the program.

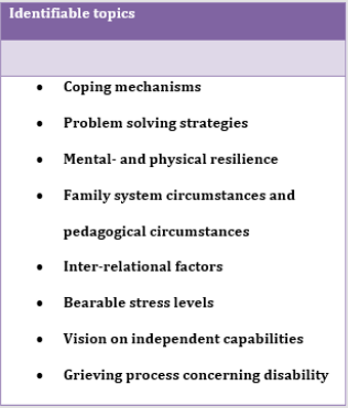

Semi-Structured Interviews with the Parent Couples: A general interview guide with important themes/topics was designed to ensure that the same general areas of information are collected from each interview [12]. This interview guide was based on the themes identified in the literature (Figure 1). The themes where chosen based on the theory of De Mönninck, 2010’, ‘van der Ploeg & Scholte, 2008’ and ‘Schreurs, et al. 1993’ [10,13,14]. All themes and topics were used to identify challenges and needs of parents. The interviews had a duration of 20 to 30 minutes and were audio taped and transcribed afterwards.

Data Analysis

The data collected from the interviews were analyzed with directed content analysis [15]. First, the transcripts of the interviews were read and important text fragments that related to the research questions, were marked. Secondly, the text fragments were coded via the ‘a-priori’ method. This method typifies itself by using a conceptual framework that is designed to make an inventory of codes the researcher expects to find in the interviews [16]. The conceptual framework used in this study was based on the theory of ‘De Mönninck, 2010’, ‘van der Ploeg & Scholte, 2008’ and ‘Schreurs, et al. 1993’. The conceptual framework was translated into the topics given in Figure 1: These topics were initially used as coding scheme. Coding proceeded until no new codes and topics emerged and analytical data saturation occurred. To interpret the data, a consensus approach was used. The first author took the lead in the analysis. A second person who was a psychologist analyzed a subset of the transcripts. After this, modifications to the labels and clustering of themes were made before establishing a final set of codes (Figure 1).

Results

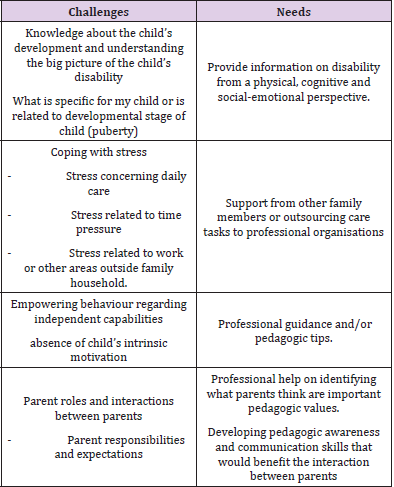

Table 2: The main four thematic challenges and needs of parents of children who completed the FITCARE4U program.

A total of 16 parent couples were interviewed, who’s child enrolled in the FitCare4U inpatient program. One parent couple was excluded from this research because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The parents of the children who participated in the research had a mean age of 48, ranging from 41 to 59. Both the father and mother were interviewed simultaneously. The children who participated in the inpatient program (n=16) consisted of 9 boys and 7 girls and had a mean age of 13,8, (ranging from 11 to 17). They were diagnosed with: Cerebral palsy (10 children with spastic cerebral palsy, 2 with Dyskinetic cerebral palsy), Spina Bifida (2), Stroke (1), McCune-Albright Syndrome (1). Eleven out of 16 children had siblings. The interviews resulted in four typical challenges and needs of parents. An overview is presented in Table 2.

Knowledge about the Child’s Development and Understanding the Overall Picture of the Child’s Disability

Challenges: Ten out of 16 parent couples /struggled with ‘Assessing the limits of their child’s disability. They did not know if certain behavior of their child was due to the disability or part of the personality and/or puberty: ‘Sometimes when I ask my daughter to help me with something and she responds that she can’t do it or that she is too tired, I often wonder whether I am physically and cognitively asking too much of her due to her disability or that she is just is a bit lazy due to her personality or age?’ (Mother of daughter of 17).

Needs: Several parents felt the need to increase their knowledge on the disability of their child. Both from a physical and cognitive perspective. They struggled with what they could ask/demand of their child with regards to independency with their child’s disability in mind. Some parents preferred to do it themselves while others would like external help. This ‘Do-ityourself approach vs outsourcing help’ were the two most common needs. ‘I think me, and my wife can do it on our own, but we could use some tips or suggestions or maybe a plan, that we can try out once our daughter returns home’ (father of daughter of 17). The majority of the parents preferred a practical solution in the form of a step-by-step plan they can take home and use as some sort of guideline. Furthermore, they felt the need for extra information on the disability or the physical/mental boundaries of the disability, or the organization of external help regarding the empowerment of their children. Other parents had difficulties formulating a possible solution that was suitable for them.

Coping with Stress in the Home Environment

Challenges: Twelve of the 16 parents interviewed identified

‘the sum of stress concerning the daily care’ and ‘stress related to

time pressure’ as challenges that could lead to relapses once the

child returned home. “The stress of encouraging and taking care of

my child during the day, drains all of my energy, this prohibits me

from being patient in certain situations. Especially if there is time

pressure to get all my children to school on time (Mother of son

of14). Particularly ‘stress related to time pressure’ was mentioned

by the majority of parents (10 of 16 parents): “the idea of the school

bus standing in front of our house and our child has not brushed his

teeth yet or has not been dressed yet, makes me nervous already

and I don’t know how to handle this in a different way” (Mother

of son of 15). The parents explained that the morning routine takes longer if you have a child with a disability. Some children/

adolescents rely on their parents to get dressed, shower or need

guidance for other personal hygienic activities.

In addition, children with Spina Bifida rely on their parents for

proper bowel irrigation or bladder catheterization. All these tasks

combined with the pressure to get ready in time, was perceived as

challenging. Several parents identified ‘stress related to work or

other external domains’ as possible failure factors once the child

returned home. “Sometimes when I arrive home from work I’m

so mentally and physically drained that I don’t have the energy

to be patient, especially if you have three children that demand

attention,” (father of son of 14). These parents explained that it was

hard for them to cope with ‘demands from work’, ‘demands from

other children’ in the family, or ‘other challenges outside of the

family’ that have an impact on the parent, besides the care of their

child with a disability.

Needs: Coping with the daily stress of taking care of a child with a disability was perceived as challenging, especially in combination with ‘time pressure’, the child’s lack of intrinsic motivation and stress from work or other domains outside the family. For example, children work on independent capabilities as brushing their teeth, help parents set the table, increasing their maximum walking distance for a better transfer in the house/school, etc. What makes it difficult and more time consuming in comparison to non-disabled children is that these children take longer to finish tasks, or still need help on certain parts of a task because of their disability. Furthermore, due to their disability and/or low performance intelligence some children are ‘over asked’ and do not understand certain tasks or know how to come up with adequate solutions. Parents feel the need to receive professional guidance on how to cope with these challenges. The parents perceived ‘support from other family members or external organizations’ as helpful with regards to holding on to the newly acquired skills and knowledge of the child. By receiving this support, the parents felt less burden with regards to the care of their child/children in combination with balancing the experienced stress. Furthermore, the need for professional guidance is expressed by the parents, to learn to deal with the time related stress.

Empowering Behavior Regarding Independent Capabilities

Challenges: The ‘absence of the child’s intrinsic motivation’ and not knowing how to cope with this absence of intrinsic motivation was also perceived as a challenge and a possible relapse factor according to the majority of the parents interviewed (12 of 16 parents): ‘I don’t know how I can motivate my child to pack his bag for school, it seems that the harder I pressure him the more he resists, which leads to me losing my patience.’(father of son of 15). Parents struggled with empowering their child to show behavior that would benefit their independency. One could argue that all parents face these challenges, but this example distinguishes itself from a non-disabled child by showing that next to a decreased intrinsic motivation, a lack of intelligence of the child and the overestimation of the child’s capabilities by parents, can increase complexity in the interaction of parents with their child. It is therefore important that parents learn the difference whether a situation is caused due to a lack of motivation or possible other factors.

Needs: The parents were convinced that parental extrinsic motivation would not be as effective as the extrinsic empowerment applied by strangers during the inpatient program. ‘I believe that children are more obedient to strangers than me as a mother for example. I don’t know why this is the case, maybe because they feel that they can be themselves around me without significant consequences?’ (mother of daughter of 17).This lead to the parents’ believe that in order to prevent relapses once the child returns home, help from professionals is needed to cope with the empowerment of their child. Nine out of the 16 parents believed they could use pedagogic tips for empowerment of their child once they returned home. Some parents would like to receive only information, while other parents were more interested in outsourcing this information and make use of professional help when they returned home.

Parent Roles and Interactions between Parents

Challenges: The parents identified several relapse factors in the domain of interpersonal relations as points of improvement to increase the chance of a successful transition home. ‘Communication between parents’ and ‘parent roles’ and ‘communication expectations’ were the most common interpersonal factors. Communicating your feelings, thoughts and expectations from mother to the father and the other way around, was perceived as helpful and would lead to more clarity for the child. In addition, it would also prevent that the child benefits from this un-clarity to refuse to do not likeable activities.

One mother stated :“My husband is by nature more patient and softer in his approach, this forces me to be more decisive. I believe I have to do this in order to compensate this and get things done. However, sometimes I would like to be soft and patient in my approach and I expect my husband to be more decisive” (Mother of daughter of 17). In other words, pronouncing expectations towards each other as parents would be beneficial, according to several parents.

Needs: The parents expressed the importance of communicating expectations towards each other as parents. Some parents could use some help identifying what they think are important pedagogic values. Furthermore, in correspondence with the knowledge gap described earlier in this chapter, it is important that the father and mother has the same information about what the disability exactly entails from a physical and cognitive perspective in order to act accordingly and adapt an unified approach as parents. In addition to this, developing communication skills that would benefit the interaction between parents was perceived as a vital need.

Discussion

This study focused on ‘the challenges and needs of parents once their child returns home from an inpatient Functional Intensive Therapy program. The goal was to focus on the perspective of parents on how to improve retainment of the positive treatment results once the child returned home. There were four challenges and four needs identified.

The First Challenge Concerned the Lack of ‘Knowledge about the Child’s Development and Understanding the Big Picture of the Child’s Disability’

Parents struggled with the situation that they did not know if

certain behavior of their child was due to his or hers disability or part

of his or hers personality and/or puberty. Parents wondered which

physical demands are realistic concerning the disability and which

behavioral demands are realistic considering the development

stage of the child? It can give parent guidance if they know on what

social-emotional level they have to interact with their child. This

need for knowledge corresponds with findings from research done

by Weis, et al. 2015 who found that caregivers wanted to increase

their parenting knowledge and increase emotional support for

themselves in order to smoothen the transition from an inpatient

program to the home environment [17].

Psycho-education on certain disabilities and more detailed

information on cognitive aspects of the disability and socialemotional

aspects of the disability should be part of any intensive

functional program. The program can guide parents in individual

or group conversations on what the disabilities entail, regarding

independent capabilities for the future. Knowledge about the

disability on what to expect regarding the future remains important

regarding the behavior of parents after the program. West, et

al. 2009 described that family-oriented rehabilitation positively

impacted the quality of life of parents after dis-charge, which made

parents more ready to cope with the pathology of their child and

therefore react more adequately. However, they presented that the

quality of life score was lower after six months than at the time of

discharge. West, et al. 2009 eluded this deterioration due to the

heavy burdens parents continue to encounter at home, related

to the fear of a relapse in the child suffering from cancer, further

surgical interventions for the child with cardiac disease, or a

progressive course of the disease in the child suffering from cystic

fibrosis [7].

They concluded that fears, worries and practical demands may cause a reduction in the achieved improvements. The results of West, et al. 2009 correspond with this research in the sense that fear is often related to certain levels of ignorance/insecurities on what to expect regarding the disability, especially if it is a progressive disability [7]. If the professionals can guide parents, during an inpatient program, on what to expect regarding the disability of their child in the short and long term, parents will be more prepared to deal with their fears whether these are realistic or not. This can give them more confidence in what they can ask of their child regarding the child’s independency. After the program it is needed to organize additional professional help in the home environment, if needed. West, et al. 2009 research also shows that in order to retain positive results it is not only important to guide parents during discharge but also the months after the program. In other words, a third recommendation is to actively monitor progress and provide guidance up to six months after the inpatient program [7].

The Second Challenge Identified was ‘Coping with Stress’. Parents Expressed the Needs to be Strengthened or Adjusted in their “Parent Capabilities and/or their Environment”

As mentioned earlier West, et al. 2009 eluded that relapses often occur due to the heavy burdens parents experience again at home, having a negative effect on the quality of life of parents. Coping with the daily stress of taking care of a child with a disability was perceived as challenging, especially in combination with ‘time pressure’, the child’s lack of intrinsic motivation and stress from work or other domains outside the family. Consistent with previous studies (Mönnink , 2010) the parent’s perceptions indicate that it is important to investigate ‘bearable stress levels’ of parents in order to set the right preconditions to facilitate new behavior on an individual and family level [10]. In case the parents needs help, an intensive intervention could be done in the form of outsourcing care tasks of parents to reduce stress. However, handling this stress is a twofold matter: Handling stress is a major component and increasing parents capability to handle stressful challenges that occur when raising a child with a disability. The second important component is decreasing stress by decreasing the amount of care tasks. Especially when parents stress is unhealthy and not bearable anymore. This can be done by outsourcing certain care tasks to professionals in order to prevent relapses of the children. This corresponds with the research done by Weis, et al. 2015 who found that caregivers felt the need to increase emotional support for themselves, and gain access to additional child and family services in order to prevent relapses [17].

The Third Challenge Identified was about ‘Empowering Behavior Regarding Independent Capabilities’

Parents struggled with empowering their child to show behavior

that would benefit their independency in the future. Sometimes

parents mirror the independency demands of their disabled child

to a non-disabled child. On the other hand, sometimes, parents

are too conservative in their approach and the children are understimulated

to reach their independency potential. This can be based

on the lack of knowledge about the disability and/or an emotional

challenge. Parents have to deal with disappointments during the

transition to adulthood of their disabled child. Consistent with

previous research done by Fernández-Alcántara, et al. 2015, it is

important to guide parents emotionally and practically with regards to feelings of loss of the ‘ideal child’ and his or hers capabilities

[18]. For example: disappointments that their child can not follow

regular education, disappointments that some children will never

experience paid employment and disappointments that some

children will never live fully independently in their own house

without professional guidance. Therefore, nurturing the ‘grieving

process’ of parents is vital to prevent relapses.

In addition to this, even though the studies from Bleyenheuft,

et al. 2017; Sakzewski, et al. 2014; Novak, et al. 2013 all found that

positive results were achieved from a physical perspective due to

high intensity therapy (in a short period of time) [1-3], you have to

take in consideration that grieving processes of parents are long and

slow of nature, and may deviate from the gained skills of the child

in an inpatient therapy program. There are several opportunities

to improve the inpatient program, for example the guidance of the

emotional processes of parents described above. During the parent

weekends there are opportunities to nurture this process as a

rehabilitation team. This can be done in individual conversations

with parents where themes as feelings of loss of the ‘ideal child’ and

how this correlates to independent capabilities, should be the main

topic of conversation. Another opportunity for the program is that

rehabilitation staff follows up on these processes after the inpatient

program, in order to increase/maintain the quality of life of parents

mentioned by West, et al. [7].

‘Parent Roles and Interactions between Parents’ was Identified as the Fourth Challenge.

The results show that pedagogic knowledge and knowledge

about the disability are both important for parents. Once you have

more knowledge about these aspects it is important to have one

unified approach as parents, when guiding the child with a disability

to adulthood. This is consistent with research done by Claes, et al.

2012 were they state that clarity about rules and agreements is

crucial for children with disabilities and lower intelligence [19].

Especially for children with a disability who have below average

performance intelligence benefit from this unified approach which

can lead to more clarity and structure for the child. As Claes, et

al. 2012 described that predictability, regularity, recognizability

and clarity should have the upper hand in raising a child with a

disability [19].

The results also show that communicating role expectations

towards each other as parents could lead to more clarity for

the child and could prevent that the child makes misuse of this

situation. Furthermore, developing communication skills that

would benefit the interaction between parents was perceived as

helpful. In other words, it is also important to look further than

the child-parent relationship. This corresponds with findings from

Lask J, et al. 1998 as they state that the distance of the inpatient unit

from the family can be an added complication. This situation may

intensify the focus onto the child and can lead to a marginalization of other important factors in the child’s family relationships and

wider environment [20]. The benefit of the positive changes of

the child after the treatment program can be diminished by what

is happening in other areas of the family household. Therefore,

it is recommendable for intensive programs to raise the parent’s

awareness about the period after the inpatient program and how to

benefit from all the gained skills.

This can be realized by including individual conversations with

parents, during the parent weekends, where social workers and

psychologists can help to identify which values are important for

both parents, communicate about the parents expectations of each

other in raising their child with a disability, and communicate about

the parents expectations regarding the future of their child in order

to manage expectations and guide the emotional process. Although

this study generated data from a specific program of Adelante and

involved a limited amount of parents, this type of program is used

in several other forms and locations which enables a generalization

of results.

Conclusion

The disengagement of a child and family from an in-patient

program towards the less intense regular care can lead to a

deterioration of the achieved improvements. The data shows that

parents struggle with feelings of fear, stress and a knowledge gap

on what the disability of their child entails. Parents felt the need

to gain more knowledge on the disability of their child, what they

can ask of their child mentally and physically and how to ask things

in order to improve the development of or retain independent

capabilities of their child. Guiding parents in voicing their parental

vision towards each other in order to empower their child with one

unified approach was perceived as important. Furthermore, the

data showed that it is important to closely monitor stress levels of

parents and intervene once stress levels are not healthy anymore,

in order to prevent a negative effect on the guiding process of their

children to independency. When generalizing the results of this

study, inpatient intensive programs should incorporate psychoeducation

on what the disability entails from a physical, cognitive

and social-emotional perspective and guide parents in what they

can ask of their child regarding independent capabilities.

Another vital component that should be included in similar

programs is guiding parents with regards to feelings of loss

of the’ ideal child’ and their journey to independency. These

disappointments come to light with regards to the adolescents’

education possibilities, paid employment and independent living.

Lastly it is important to keep monitoring and guiding parents after

discharge of the child in order to prevent relapses on a parent and

child level. The mentioned challenges will be ongoing processes

for parents in guiding their child to independency and should be

subject of inpatient programs and regular care afterwards. Further

research is required to measure the identified challenges before the inpatient program and three months after the inpatient program .

This can give more insight on the effectiveness of the interventions

during this period.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study and approval of the ethical committee was not necessary due to the fact that the study was part of the usual care.

References

- Sakzewski L, Gordon A, Eliasson A (2014) The state of the evidence for intensive upper limb therapy approaches for. J Child Neurol 29(8): 1077-1090.

- Novak I, Mc Intyre S, Morgan C, Campbell L, Dark L, et al. (2013) A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: state of. Dev Med Child Neurol 55(10): 885-910.

- Bleyenheuft Y, Ebner Karestinos D, Surana B, Paradis J, Sidiropoulos A, et al. (2017) Intensive upper- and lower-extremity training for children with bilateral. Dev Med Child Neurol 59(6): 625-633.

- Roelofsma R, Rameckers E (2017) The Effect of a Functional Intensive Intervention Program on Self-Care in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Case Study. Int J Brain Disord Treat 3: 021.

- Gill F, Butler S, Pistrang N (2016) The experience of adolescent inpatient care and the anticipated transition to the. J Adolesc 46: 57-65.

- Hepper F, Weaver T, Rose G (2005) Children's understanding of a psychiatric In-Patient Admission. Clinical child Psychology and Psychiatry 10(4): 557-573.

- West C, Besier T, Borth Bruhns T, Goldbeck L (2009) Effectiveness of a family-oriented rehabilitation program on the quality of life. Klin Padiatr 221(4): 241-246.

- Jacobs B (1998) The treatment and discharge phases of admission. , in Inpatient child psychiatry: Modern practice research and the future B.W.J. J. M. Green, (Eds.). Routledge, London.

- Green J, Jones D (1998) Unwanted effects of inpatient treatment: anticipation, prevention, repair. Inpatient child psychiatry: Modern practice research and the future, (Edi.), B.W.J. J. M. Green. 1998, London: Routledge, pp. 212-219.

- Mönnink HJd (2009) De gereedschapskist van de maatschappelijk werker, in Handboek multimethodisch maatschappelijk werk., M.H. de, (Edi.). 2010, Elsevier: Maarssen.

- Baarda B, Bakker E, Boullart A, Fischer T, Julsing M, et al. (2018) Basisboek Kwalitatief onderzoek. 4 (Edn.), Groningen: Noordhoff uitgevers B.V.

- Silverman D (2011) Interpreting qualitative data. London Sage.

- Schreurs P, Van de Willige G, Brosschot J, Tellegen B, Graus G, et al. (1993) UCL. Omgaan met problemen en gebeurtenissen. Amsterdam: Pearson.

- Van der Ploeg J, Scholte E (2008) Handleiding Gezinsvragenlijst GVL. Houten: bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15(9): 1277-1288.

- Mortelmans D (2011) Kwalitatieve analyse met Nvivo, (Edi.). Acco. Leuven: Acco.

- Weiss C, Blizzard A, Vaughan C, Sydnor Diggs T, Edwards S, et al. (2015) Supporting the transition from inpatient hospitalization to school. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 24(2): 371-383.

- Fernandez Alcantara M, Garcia Caro M, Laynez Rubio C, Perez Marfil M, Marti Garcia C, et al. (2015) Feelings of loss in parents of children with infantile cerebral palsy. Disabil Health J 8(1): 93-101.

- Claes L, De Neve L, Declercq K, Jockheere B, Merrecau J, et al. (2012) Emotionele ontwikkeling bij mensen met een verstandelijke beperking. (Eds.). A.S.E.v.z.w.G.-U. n.v.

- Lask J, Maynerd C (1998) Engaging and working with the family. , in Inpatient child psychiatry: Modern practice research and the future B.W.J. J. M. Green, (Eds.). 1998, Routledge, London, p. 75-91.

Research Article

Research Article