Abstract

Introductionː the availability of screening and the existence of a specific diagnostic and therapeutic process has favored early diagnosis of cervical cancer. Performing radical hysterectomy (RH) (type III Piver or type C2 Querleu), pelvic nerves and fascial structures can be interrupted in the anterior, posterior and lateral parametrium, leading to various degrees of bladder dysfunction. In literature, various studies have found that the reduction of radicality on parametria in early cervical cancer (ECC) leads to lower complications rate, without influencing oncological outcomes. Unfortunately, only few data are now disposable, and evidences are not so clear. The aim of our review is to evaluate how “less radical surgery” on parametria and NSRH (Nerve Sparing Radical Hysterectomy), in the specific population of ECC, could impact on bladder function, comparing it with a more radical approach.

Material and Methods: Searching on Pubmed, we included 1473 articles published from January 1974 to September 2020. We identified all studies that compared different techniques of radical hysterectomy as primary surgical treatment of ECC. Then, we focused our analysis on bladder functionality after surgical treatment: 10 articles were included in our review.

Result: Radical hysterectomy Piver II/Querleu-Morrow Type B in ECC, if compared to classic radical hysterectomy (Piver III/Querleu-Morrow Type C2), is associated with minor bladder dysfunction. Nerve sparing radical hysterectomy approach (NSRH/ Querleu-Morrow Type C1) compared to CRH (Piver III/Type C2) in the ECC, seems to give a better urologic outcome after surgery.

Conclusionsː Reduced radicality on the parametrium in the specific population of ECC (stages IA-IIA FIGO) offers positive effects on patients’ bladder function.

Keywords: Nerve-Sparing Radical Hysterectomy Bladder Dysfunction; Radical Hysterectomy Bladder Dysfunction; Bladder Dysfunction Early Cervical Cancer

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the 2nd tumor in frequency among women aged 15 to 44 worldwide [1]. Conventional surgical treatments recognized by the international Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics for early cervical cancer (ECC) (stage I - IIA) are radical hysterectomy and radical trachelectomy [2,3]. Performing classic radical hysterectomy (CRH) (type III Piver or type C2 Querleu), pelvic nerves and fascial structures can be interrupted in the anterior, posterior and lateral parametrium, leading to various degrees of bladder dysfunction. Radical surgery is associated to significant bladder dysfunctions, that occurs in majority of patients, ranging from 8 to 80% [4-8]. ECC provides the possibility of performing tailored surgical interventions according to patient’s needs, guarantying contemporary either adequate oncological result or quality of life (QoL). To improve QoL, in 1998, the concept of nerve sparing surgery emerged: it allows the salvation of autonomic function of the pelvis, reducing urinary, sexual and rectal dysfunctions. Nerve sparing surgical technique involves a first step with completion of pelvic lymphadenectomy and resection only vascular part of cardinal ligament to preserve the autonomic nerves within the neural part.

After, a second step follow with incision of the rectouterine peritoneal fold with separation of the anterior mesorectum from the proximal vagina, follow identification and separation of hypogastric nerves (HN) on the rectal side. While dissecting the rectovaginal ligament, care is taken to avoid injuries to the pelvic plexus. Finally, bladder branches of inferior hypogastric nerves of the pelvic plexus, along the posterior sheath of the vesicouterine ligament, are identified and conserved. Despite growing evidence shows that Nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy (NSRH) guarantees reduced risk of surgical‑related pelvic dysfunction with similar oncological outcome as CRH, it is not a current standard for ECC treatment [9]. Recent literature in ECC is orientated to found evidence that reducing the radicality on the parametria could reduce complications without impacting oncological outcomes: anyway, data are not yet clear [10,11]. The aim of our review is to evaluate how “less radical surgery” on parametria and NSRH (Nerve Sparing Radical Hysterectomy), in the specific population of ECC, could impact on bladder function, comparing it with a more radical approach.

Materials and Methods

We included articles published from January 1974 to

September 2020 on PUBMED. We identified all the studies that

compared different type of radical hysterectomy in the primary

surgical treatment of early cervical cancer. The keyword that were

used in this review are: bladder dysfunction early cervical cancer,

nerve sparing radical hysterectomy early cervical cancer, radical

hysterectomy cervical cancer IB, Piver radical hysterectomy early

cervical cancer. Moreover, MeSH keyword search and free text

were used. We excluded review articles, retrospective articles,

comments, letters, conference proceedings, absence urologic data,

articles with comparison between surgery and chemotherapy

and/or radiotherapy, articles including locally advanced cervical

cancer (stage IIB FIGO or more). We included only studies that met

the following inclusion criteria: prospective design, early cervical

cancer (stage I-IIA FIGO), comparison between different surgical

techniques on parametria and presence of urologic data on bladder

function after radical surgery. Considering recent results of the

LACC trial by Ramirez et al. we excluded procedures done with

minimally invasive surgery [12].

All included studies were conducted on humans. We excluded

not “full text” articles. Study Selection, Data Extraction and Data

Synthesis Study selection were independently carried out by

two authors (F.P. and F.F.). Titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility according to inclusion and exclusion criteria, and

when considered ineligible them were excluded. Differences in

judgment during the selection process between the reviewers were

discussed to find a consensus. Information was collected using an

Excel spreadsheet. For each study, data about year of publication,

study type and sample size for the two surgical techniques were

collected. The perioperative urologic variables were assessed

for each group: duration of postoperative catheterization (mean

days), stress incontinence, urgency/frequency, voiding difficulty/

dysuria, nocturia, post-void residual volume<70 ml, neurogenic

bladder and bladder compliance (ml/cmH20). Included studies

were heterogeneous and, for this reason, a meta-analysis was not

feasible[13-20].

Results

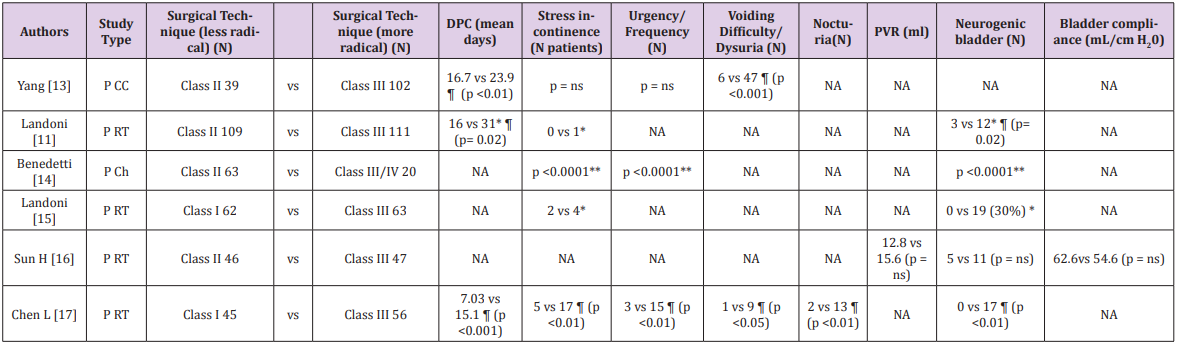

Searching on PubMed, we included 1473 articles. Study selection flowchart was showed in Figure 1.Urologic outcomes for the different type of radicality are shown in Table 1. It can be seen that radical hysterectomy Querleu-Morrow type C2 / Piver III is associated with a longer postoperative catheterization if compared to Piver I/II in all the groups (p < 0,001 and p = 0.02 respectively). Differences about post-void residual volume (PVR) and bladder compliance were not significant between the two groups. About urologic symptoms: “urgency/frequency” and “voiding difficult/ dysuria” were higher in the group treated with more radical surgery than in the other group. This difference was statistically significant in two articles for both symptoms, while the other four articles did not specify this data. Differences about nocturia were statistically significant for one article, while other five articles did not specify this data. Regarding stress incontinence after surgery, it was lower in radical hysterectomy Piver I/II than Piver III/IV in four articles: unfortunately, only in two articles the difference was statistically significant.

Table 1: Studies with different radicality approach on parametria in early cervical cancer (Stage IA-IIA FIGO): postoperative urologic parameters

Ch: Cohort, CC: case-control, P: prospective, RT: Randomized trial, DCP: duration of postoperative catheterization, PVR: Post-void residual volume, CRH: Classic Radical Hysterectomy, NSRH: Nerve sparing radical hysterectomy, NA: not available; ns: not significant; ¶: Statistically significant P value; * without radiotherapy; **Panici, et al. [14] give globally result long-term complications, bladder dysfunctions overactive detrusor, mixed urinary incontinence, de novo stress incontinence, acontractile detrusor were significantly more frequent in RH Class III/IV than in Class II patients, being present in 70% and 11% of the cases, respectively (P <0.0001)

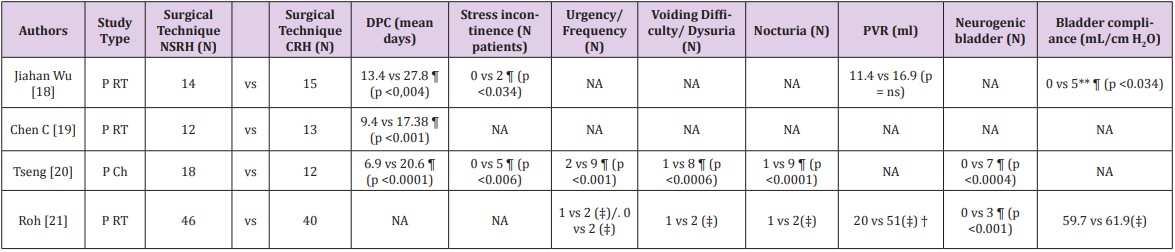

Table 2: Studies with comparison between radical hysterectomy vs NSRH in early cervical cancer (Stage IA-IIA FIGO): postoperative parameters

Ch: Cohort, CC: case-control, P: prospective, RT: Randomized trial, CP: duration of postoperative catheterization, PVR: Post-void residual volume, CRH: Classic Radical Hysterectomy, NSRH: Nerve sparing radical hysterectomy, NA: not available; ns: not significant; ¶: Statistically significant P value; * without radiotherapy; ‡ p<0.05 compared with preoperative basal data by Wilcoxon signed rank test.** Wu et al report the number of the case of Low Bladder compliance and no urodynamic data; †: The median duration before the postvoid residual urine volume became less than 50 mL was 11 vs 18 (days) respectively ¶ (p <0.001)

Neurologic bladder was analyzed in five studies: in three

studies the difference was statistically significant, in one there

was not a significant difference between the groups and in the

last the difference was 30% higher in group treated with more

radical surgery (in this study, p value was not reported). Urological

data reported by the studies that evaluated the classic radical

hysterectomy in comparison with the nerve sparing techniques

were included in the postoperative data in Table 2. Considering

the “duration of postoperative catheterization”, it was analyzed in

three articles and it was lower in NSRH if compared to the group

treated with radical hysterectomy Querleu-Morrow type C2 / Piver

III. These data were all statistically significant (p<0.004). The

incidence of “Stress incontinence” was higher in the group treated

with CRH than NSRH, with 0% in NSRH group and between 13-41%

in CRH group.

“Bladder compliance” was better in NSRH group than CRH in the

two articles: the first article reported statistically significant data,

while the second one showed only a worst result of CRH considering

preoperative urodynamic data. About PVR, it is indicated in two

articles: in all of the cases, NSRH showed lower PVR than CRH but

there is not a statistically significant value expressed in ml. Roh’s

article shows that the median duration before that the postvoid

residual urine volume becomes less than 50 mL is 11 days vs 18

days (p <0.001) [21]. Regarding urologic symptoms like “urgency/

frequency”, “voiding difficult/dysuria” and “nocturia”, NSRH offers

better results than CRH: these facts is reported in two articles, but

only one article’s results are statistically significant. Lastly, the

number of patients with neurologic bladder was lower in NSRH

than CRH group and the result was statistically significant in both

the two articles reported.

Discussion

A new era in oncologic surgery is taking hold: a tailored surgery that offers individual treatment to the individual patient. Increasing evidence and numerous researchers ask themselves if demolishing more means a better prognosis for patients [11,15]. The treatment proposed in our review is applicable in selected cases of ECC (favorable risk factors such as tumor size ≤ 2 cm or invasion depth < 10 mm and absence of LVS, the risk of parametric involvement is less than 1% (0.4-0,6%) [22-25]), remembering that during extensive radical surgery it is possible to damage the pelvic organs in a more or less reversible way. In a previous article, we indicated that the incidence of bladder dysfunction after RH is about 72% [26]. Anatomical studies demonstrated that the pelvic autonomic nerve plexus, namely, the hypogastric nerve and splanchnic nerves, lies within a loose tissue sheath underneath the ureter, lateral to the sacrouterine ligaments and within the dorsomedial side of the neural part of the cardinal ligament, at the bottom of the pararectal space [27]. Vaginal, urinary, and bowel symptoms are the result of surgical trauma involving the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomous nerves and blood supply of pelvic organs [28].

In fact, during radical hysterectomy procedure, the most damaging steps are vaginal, anterior and posterior parametrium resection. The damage appears to be related to the parasympathetic roots of the S3 and S4 nerves, which make up hypogastric sheath, and shortly after join with the hypogastric (sympathetic) nerves to form the pelvic plexus very close to the anterolateral side of the lower rectum, near the anorectal junction. The pelvic plexus gives rise to postganglionic fibers, which lie as a flat meshed band on the lateral wall of the upper third of the vagina. These fibers reach the bladder through the deep layer of the cervico-vesical and the vagino-vesical ligaments [26]. Results obtained in our review show that a less radical intervention on the parameters is related to a reduction in duration of post-operative catheterization, probably linked to a lower denervation phenomenon that occurs during tissue resection process. NSRH also offers better results than CRH in term of reduction of post-operative catheterization, although the NSRH range (6.9 -13.4 days) is substantially comparable to less radical RH surgery (Class I / II Piver) (7.03 -16.7 days). Regarding bladder compliance parameters, two studies, published respectively by Sun H et al. and Jihan Wu et al., report a reduction in bladder compliance in the CRH group if compared to Piver II or NSRH. On the contrary, Roh et al. [21] report similar bladder compliance between the two surgical treatments [16,18,21].

A lower bladder compliance results from decreased elasticity of the bladder wall: it is shown in the urodynamic tracing as a loss of accommodation with a gradual pressure increase during filling. Probably this result was linked to a different follow-up in the articles: studies that provided follow-up shorter than 12 months showed a higher incidence (73%) of better bladder compliance if compared to long-term trials [29]. Ralph, et al. [30]have performed urologic evaluations and urodynamic studies at one year after abdominal hysterectomy for cervical cancer, and they revealed that two weeks after surgery bladder compliance was low in 33 patients (82.5%) and normal in seven (17.5%), while, after one year, compliance became high in 16 patients (40%) [30].The scientific reason behind this modification could be understood with animal and human models that show phenomena of neuronal plasticity following damage. In fact, Haferkamp et al. [31]studied a feline model of bladder decentralization after extirpation of the pelvic plexus. They demonstrated that short-term changes at 3 weeks are degeneration of intrinsic axons and muscle cells that cause lower of bladder compliance.

Long-term changes at 10 weeks include a reversal of degeneration with restitution of cholinergic axon terminals, increase in adrenergic and copeptidergic axons, muscle cell regeneration: these facts conduce to an increased bladder compliance [31]. Stress urinary incontinence was increased in the group performing more demolitive surgery if compared to Piver Class I/II and NSRH surgery. Probably, a worse result is due to the damage of the pelvic plexus and pudendal nerves with loss of periurethral tone. This is determined by the loss of sympathetic/ adrenergic stimulation due to surgical damage: it may have an excitatory effect on parasympathetic transmission to the detrusor muscle during urine storage and may lead to permanent relaxation of the bladder neck and the proximal urethra, explaining the high incidence of detrusor over activity and urinary stress incontinence after radical hysterectomy [32,33]. Axelsenet al. [34]in their study confirmed the role of the urethral sphincter mechanism. In this study assessing urethral pressures during the voiding phase, 50 women reported continence after RH and 50 women reported urinary incontinence.

The 100 women included in this study were matched: no differences in urodynamic findings were observed between the two groups, except for a difference in intra-urethral pressure. The authors concluded that a decrease in the urethral pressure could contribute to the characterization of incontinence after RH [34]. Regarding urgency, frequency and nocturia were higher in our review in CRH group if compared to both NSRH and RH Piver Class I/II: this fact is probably linked to disruption of sympathetic/ adrenergic nervous fibers. The resection of autonomic fibers innervating the bladder can happen at several stages during radical hysterectomy: during dissection of the presacral or superior gluteus nodes, during vaginal dissection and mobilization of the bladder and during resection of the cardinal ligament. PVR was not different between the different types of radical hysterectomy, but an interesting data was reported by Rho, et al. [21]. They showed that the median duration before that the post-void residual urine volume becomes less than 50 mL is 11 days vs 18 days for NSRH and CRH respectively (p <0.001).

Neurogenic bladder, due to peripheral damage with atonic bladder and urine retention, was higher in CRH group than Piver Class I/II, and this event was completely absent in NSRH group. This manifestation is present when the sympathetic nervous system is active, urinary accommodation occurs and the micturition reflex is inhibited. This event can occur in presence of different confounding factors like opioid use or anesthetics or surgical pain, via activation of the sympathetic nervous system that leads to detrusor relaxation and bladder neck contraction—essentially a constant bladder filling stage as described by the mechanisms above. However, there are many additional methodological biases in the previous published studies. These include mostly the sample size and incomplete urological data from the different studies and different period of follow-up considered.

Conclusion

Our review highlights how modified radical hysterectomy (Piver II /Querleu-Morrow Type B) in ECC, if compared to CRH (Piver III / Querleu-Morrow Type C2), is associated with better urologic outcome after surgery. About the nerve sparing radical hysterectomy approach (NSRH/ Querleu-Morrow Type C1) compared to CRH (Piver III / Type C2) in the ECC, our data can confirm a superiority regarding the urologic outcome. From the preliminary tests, it seems that a reduced radicality on the parametrium offers positive effects on urologic outcome. It should always be considered to avoid an excessive treatment of ECC and offer a tailored treatment. Despite the results of our review, we need randomized studies in the future to confirm its safety from an oncological point of view in patients with ECC, given the small number of patients in most of the current randomized studies.

References

- Altobelli E, Lattanzi A (2015) Cervical Carcinoma in the European Union: An Update on Disease Burden, Screening Program State of Activation, and Coverage as of March 2014. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2015;25(3): 474-483.

- Ditto A, Martinelli F, Borreani C, Kusamura S, Hanozet F, et al. (2009) Quality of life and sexual, bladder, and intestinal dysfunctions after class III nerve‑sparing and class II radical hysterectomies: A questionnaire‑based study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 19(5): 953‑

- Kim HS, Choi CH, Lim MC, Chang SJ, Kim YB, et al. (2012) Safe criteria for less radical trachelectomy in patients with early‑stage cervical cancer: A multicenter clinicopathologic study. Ann Surg Oncol 19: 1973‑

- Vervest HAM, Barents JW, Haspels AA, Frans MJ Debruyne (1989) Radical hysterectomy and the function of the lower urinary tract. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 68(4): 331-340.

- Forney JP (1980) The effect of radical hysterectomy on bladder physiology. Am J Obstet Gynecol 138(4): 374-382.

- Low JA, Mauger GM, Carmichael JA (1981) The effect of Wertheim hysterectomy upon bladder and urethral function. Am J Obstet Gynecol 139(7): 826-834.

- Scotti RJ, Bergman A, Bhatia NN, Donald Ro (1986) Urodynamic changes in urethrovesical function after radical hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 68: 111-120.

- Ralph G, Winter R, Michelitsch L, Tamussino K (1991) Radicality of parametrial resection and dysfunction of the lower urinary tract after radical hysterectomy. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 12(1): 27-30.

- Lee SH, Bae JW, Han M, Cho YJ, Park JW, et al. (2020) Efficacy of nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy vs. conventional radical hysterectomy in early-stage cervical cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Clin Oncol 12(2): 160-168.

- Derks M, van der Velden J, Frijstein MM, Vermeer WM, Stiggelbout AM, et al. (2016) Long-term pelvic floor function and quality of life after radical surgery for cervical cancer: a multicenter comparison between different techniques for radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 26: 1538-1543.

- Landoni F, Maneo A, Cormio G, Perego P, Milani R, et al. (2001) Class II versus class III radical hysterectomy in stage IB-IIA cervical cancer: a prospective randomized study. Gynecol Oncol 80(1): 3-12.

- Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, Lopez A, Vieira M, et al. (2018) Minimally Invasive versus Abdominal Radical Hysterectomy for Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med 379(20): 1895-1904.

- Yang YC, Chang CL (1999) Modified radical hysterectomy for early Ib cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 74(2): 241-244.

- Panici PB, Angioli R, Palaia I, Muzii L, Zullo MA, et al. (2005) Tailoring the parametrectomy in stages IA2-IB1 cervical carcinoma: is it feasible and safe?. Gynecol Oncol 96(3): 792-798.

- Landoni F, Maneo A, Zapardiel I, Zanagnolo V, Mangioni C (2012) Class I versus class III radical hysterectomy in stage IB1-IIA cervical cancer. A prospective randomized study. Eur J Surg Oncol 38(3): 203-209.

- Sun H, Cao D, Shen K, Yang J, Xiang Y, et al. (2018) Piver Type II vs. Type III Hysterectomy in the Treatment of Early-Stage Cervical Cancer: Midterm Follow-up Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Oncol 8: 568.

- Chen L, Zhang WN, Zhang SM, Gao Y, Zhang TH, et al. (2018) Class I hysterectomy in stage Ia2-Ib1 cervical cancer. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 13(4): 494-500.

- Wu J, Liu X, Hua K, Hu C, Chen X, et al. (2010) Effect of nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy on bladder function recovery and quality of life in patients with cervicalvcarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer 20(5): 905-909.

- Chen C, Li W, Li F, Fengjuan Li, Xiangzhao Li, et al. (2012) Classical and nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy: an evaluation of the nerve trauma in cardinal ligament. Gynecol Oncol 125(1): 245-251.

- Tseng CJ, Shen HP, Lin YH, Lee CY, Wei-Cheng Chiu W (2012) A prospective study of nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy for uterine cervical carcinoma in Taiwan. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 51(1): 55-59.

- Roh JW, Lee DO, Suh DH, Lim MC, Seo SS, et al. (2015) Efficacy and oncologic safety of nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Gynecol Oncol 26(2): 90-99.

- Benedetti Panici, Maneschi F (2000) Early cervical carcinoma: the natural history of lymph node involvement redefined on thecbasis of thorough parametrectomy and giant section study. Cancer 88: 2267-2274.

- Wright JD, Grigsby PW, Brooks R, Powell MA, Gibb RK, et al. (2007) Utility of parametrectomy for early stage cervical cancer treated with radical hysterectomy. Cancer 110(6): 1281-1286.

- Stegeman M, Louwen M, van der Velden J, FJ W ten Kate, MA den Bakker, et al. (2007) The incidence of parametrial tumor involvement in select patients with early cervix cancer is too low to justify parametrectomy. Gynecol Oncol 105(2): 475-480.

- Frumovitz M, Sun CC, Schmeler KM, Deavers MT, Reis RD, et al. (2009) Parametrial involvement in radical hysterectomy specimens for women with early-stage cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol 114(1): 93-99.

- Plotti F, Angiolia R, Zullo MA, Sansone M, Altavilla T, et al. (2011) Update on urodynamic bladder dysfunctions after radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 80(2): 323-329.

- Yabuki Y, Asamoto A, Hoshiba T, Nishimoto H, Nishikawa Y, et al. (2000) Radical hysterectomy: an anatomic evaluation of parametrial dissection. Gynecol Oncol 77(1): 155-163.

- Maas CP, Kenter GG, JTrimbos JB, Deruiter MC (2005) Anatomical basis for nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy: immunohistochemical study of the pelvic autonomic nerves. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 84(9): 868-874.

- Carenza L, Nobili S, Giacobini S (1982) Voiding disorders after radical hysterectomy. Gynecol Oncol 13(2): 213-219.

- Ralph G, Tamussino K, Lichtenegger W (1988) Urodynamics following radical abdominal hysterectomy for cervical cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet 243: 215-220.

- Haferkamp A, Dorsam J, Resnick NM (2003) Structural basis of neurogenic bladder dysfunction. III. Intrinsic detrusor innervation. J Urol 169(2): 555-562.

- Benedetti-Panici P, Zullo MA, Plotti F, Manci N, Muzii L, et al. (2004) Long-term bladder function in patients with locally advanced cervical carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and type 3-4 radical hysterectomy. Cancer 100(10): 2110-2117.

- Zullo MA, Manci N, Angioli R, Muzii L, Panici PB, et al. (2003) Vesical dysfunctions after radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer: a critical review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 48(3): 287-293.

- Axelsen SM, Bek KM, Petersen LK (2007) Urodynamic and ultrasound characteristics of incontinence after radical hysterectomy. Neurourol Urodyn 26(6): 794-799.

Review Article

Review Article