Abstract

The CoVid-19 pandemic resulted in a shockwave that left many industries paralyzed. Despite previous progress in the Biomedical MEMS (BioMEMS) industry, and the enormous research with revolutionizing capabilities in ultrasensitive MEMS- based biosensors, the BioMEMS industry was noticeably absent during the pandemic, and none of the promising MEMS-based biosensing techniques was able to stand to the CoVid-19 pandemic. This is an indication that the BioMEMS industry is still in a very early embryonic stage, a rethinking of the BioMEMS research needs to be implemented.

Keywords: BioMEMS; CoVid-19; Corona viruses; Severe Acute Respiratory; Telecommunication

Abbreviations: MERS: Middle East Respiratory Syndrome; SARS: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; MEMS: Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; ELISA: Enzyme Linked Immuno Sorbent Assay

Introduction

Recently significant efforts have been performed to understand the function of the SARS-CoV-2 virus which causes CoViD-19. Devices based on the BioMEMS technology (Micro-Electro- Mechanical Systems for Biomedical applications) have been widely investigated for potential use in sensing and detection of viral antigens, and characterization of associated proteins in the family of BioMEMS technologies known as Lung-on-a-Chip [1,2]. Corona viruses were first discovered in 1965 by Tyrrell and Bynoe, who identified the B814 virus, followed by the discovery of the 229E virus by Hamre and Prockow [3]. These viruses and other corona viruses that were identified later such as the NL63, OC43, and HKU1 were known to cause a multitude of mild respiratory tract illnesses such as some types of the common cold. They are responsible for 5-15% of upper respiratory tract illnesses [4]. Coronaviruses that evolved from animals are known to cause severe acute respiratory illnesses such as the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERSCoV) which was identifed in 2012, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV) identified in 2003, and the SARS- CoV-2 which causes CoViD-19 (also known as the 2019 Novel Coronavirus disease).

The spread of the Coronavirus pandemic resulted in a series of shockwaves that struck in almost every aspect of the human civilization. The Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) industry was one of the industries that were impacted uniquely from the pandemic. The pandemic shockwave resulted in a hardhit automotive industry sector with a decline of -27.5 % and an aviation industry almost paralyzed. However, some industries experienced a surge in demand, such as the electronic commerce and retail delivery services and the Telecommunication MEMS industries experienced an overall positive growth [5]. Another noticeable effect was the surge in collaborative research to even forming consortia such as the COVID R&D group that included multiple pharmaceutical groups [6] and the trend to develop selfsufficiency in the supply chain [7].

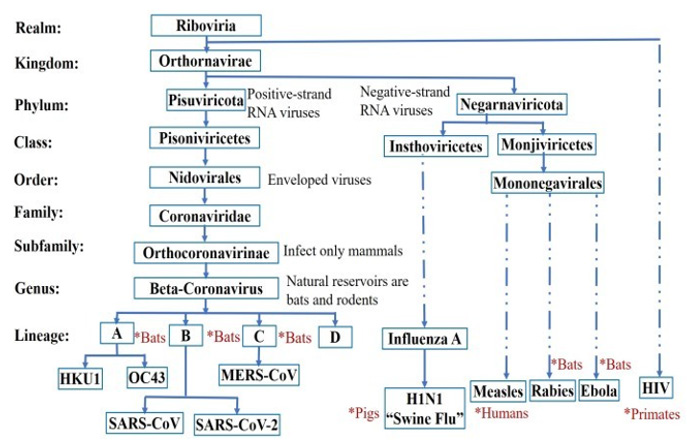

The pandemic has negatively and positively affected the BioMEMS market. According to the 2020 Yole Development report, the BioMEMS market will grow at a compound annual growth rate of 9.2%, this is a significant drop from previously predicted growth rate of 19% before the pandemic [8]. According to the report, microfluidics make up 85% of the size of the BioMESM market. Although the microfluidics market will grow at a rate of 17.9% from 2020 to 2027 according to Report Linker, this is due to the increase in demand for Point- of-Care (POC) diagnosis [9]. However, SARSCoV- 2 will not be the last virus to cause a pandemic nor the most lethal. It is estimated that there are between 650,000 and 840,000 unknown virus species in the wildlife that can infect humans [10]. Eventually, with the increase in human population and the reduction in natural habitat for the wildlife, contact between humans and these viruses will be inevitable. Figure 1 shows the lineage for the SARS-CoV-2 with respect to some known viruses, and their natural hosts.

Bats form the second largest mammalian species by population after rodents, existing almost everywhere on the earth except in Antarctica and the arctic circle. They have a very high mobility and very social lives. Some bat colonies are known to have populations as large as 20 million bats such as the Bracken Bat Cave colony [11- 13]. Therefore, bats are believed to be the natural hosts for a wide range of known viruses such as Rabies, Ebola, SARS-CoV-2, and HKU1 and OC43 which cause the common cold [14,15]. The process by which a virus jumps from wildlife to humans is referred to as Zoonotic Spillover [14]. Some of the viruses that jumped to humans include very deadly ones such as Rabies (from bats), incurable ones such as HIV (from primates), and very contagious ones such as smallpox (from rodents). Based on lessons learned from the Covid-19 pandemic, preparations must be taken on the long-term strategic and scientific levels for future pandemics that may affect humanity.

The Pandemic and the Biomems Industry

Currently the two standard testing methods used to detect viral infections are based on Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), used for detection of virus antigens, and Enzyme Linked Immuno Sorbent Assay (ELISA), which is used to detect antibodies [16,17]. Historic diagnostic devices were developed in which PCR is performed to amplify arrays of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR). Methods based on CRISPR have been developed such as the one-hour test for SARS-CoV-2 developed by Sherlock Biosciences, and the 20-minute test developed by Mammoth Biosciences and GlaxoSmithKline [18]. The main absentee from the picture is the BioMEMS industry. Both PCR and ELISA are conventional methods that are not based on MEMS.

Despite the enormous amount of publications over the last two decades in ultra-sensitive MEMS-based biosensors and biological characterization techniques that promised to revolutionize biological sensing and detection, from prominent institutions and research centers around the globe, none of BioMEMS technologies was able to show any use when the world faced the first real test of the CoVid-19 pandemic. Leichle et. al report that in 2019 alone more than 160 publications described novel MEMS-based sensors [17]. This catastrophic absence of the BioMEMS industry may indicate that the industry is still in the embryonic stage, and that despite showing promising results in ultra-sensitivity, the MEMSbased sensing techniques lack repeatability. Therefore, a rethinking of the BioMEMS research needs to be implemented at the academic institutional level, and a new trend in the scientific community needs to take into account more thorough analysis of repeatability and reliability of results.

Conclusion and Discussion

Over the last two decades, an enormous number of works had been reported in literature of revolutionizing and state-of- the-art biosensing techniques in the BioMEMS industry. However, when came the first real pandemic test, the industry was completely silent, and none of the promising MEMS-based biosensors was able to be of any use. This absence can indicate an industry that is still in the embryonic stage in biosensing and poor repeatability in achieved results. It may also be a result of complexity of the MEMSbased sensing mechanisms, that rendered them useless with respect to other methods. A rethinking in the BioMEMS industry needs to take into account improving repeatability of MEMS-based biosensors mechanisms.

References

- J Shrestha, Woolcock, S R Bazaz, H A Es, D Y Azari, (2020) Lung-on-a- chip: the future of respiratory disease models and pharmacological studies. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 40: 213-230.

- N Azizipour, R Avazpour, D H Rosenzweig, M Sawan, A Ajji (2020) Evolution of Biochip Technology: A Review from Lab-on-a-Chip to Organ-on-a-Chip. Micromachines 11(6): 599.

- J S Kahn, K Mc Intosh (2005) History and Recent Advances in Coronavirus Discovery. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 24(11): S223-S227.

- A R Falsey, R M Mc Cann, W Hall, M M Criddle, M Formica (1997) The ‘‘Common Cold” in Frail Older Persons: Impact of Rhinovirus and Coronavirus in a Senior Daycare Center. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 45(6): 706-711.

- (2020) MEMS industry: the headwinds from COVID-19 and the way forward. Yole Development.

- D Kwon (2020) How the Pharma Industry Pulled Off the Pivot to COVID-19. The Scientist.

- N Ayati, P Saiyarsarai, S Nikfar (2020) Short and long term impacts of COVID-19 on the pharmaceutical sector. DARU Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences.

- (2020) BioMEMS industry growth forecast reduced despite Covid stimulus. EE News Europe Analog Lasne Belgium.

- (2020) Microluidics Market Market Forecast to 2027-COVID- 19 Impact and Global Analysis by Product, Material, Application and Geography. Report Linker Lyon France.

- M C Lu (2020) Future pandemics can be prevented, but that’ll rely on unprecedented global cooperation. The Washington Post.

- B Hu, X Ge, L F Wang, Z Shi (2015) Bat origin of human coronaviruses. Virology Journal 12: 221.

- A Mannan, A Nausheen (2020) A literature review of severe acute respiratory disorder (SARS): Corona virus. The Pharma Innovation Journal 9(5): 84-95.

- P M Stepanian, C E Wainwright (2018) Ongoing changes in migration phenology and winter residency at Bracken Bat Cave. Global Change Biology 24: 3266- 3275.

- K J Olival, P R Hosseini, C Zambrana Torrelio, N Ross, T L Bogich (2017) Host and viral traits predict zoonotic spillover from mammals. Nature 546: 646-650.

- D G Streicker, A S Turmelle, M J Vonhof, I V Kuzmin, G F Mc Cracken (2010) Host phylogeny constrains cross-species emergence and establishment of rabies virus in bats. Science 329: 676-679.

- J Xiang, M Yan, H Li, T Liu, C Lin, (2020) Evaluation of Enzyme-Linked Immunoassay and Colloidal Gold- Immunochromatographic Assay Kit for Detection of Novel Coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) Causing an Outbreak of Pneumonia (COVID-19). MedRXiV.

- T Leichlé, L Nicu, T Alava (2020) MEMS biosensors and COVID-19 : missed opportunity. Sensors.

- C Sheridan (2020) COVID-19 spurs wave of innovative diagnostics. Nature Biotechnology 38: 769-772.

Mini Review

Mini Review