Abstract

The aim of the study was to examine the effect of physical activity (PA) training on immune system indices while providing chemotherapy. The retrospective research was conducted at the Oncology Department of Barzilai Hospital, Israel. 62 chemotherapy treated participants aged 47-93 years met the inclusion criteria of pre and post-exercise blood tests. 17 were men (27.4%). The PA training protocol constituted of 15 minutes daily exercise. The first instructions were given by a physiotherapist at the day of chemotherapy and supervised thereafter. Training consisted of exercises to develop muscle endurance, aerobic fitness, coordination and agility in a low-intensity mode adapted to the patients’ condition. The investigative time duration ranged from 1 to 19.5 weeks; categorized as three groups. Group A: 1 to 4.5 weeks, Group B: 5 to 9 weeks and Group C: 12 to 19.5 weeks. Immune system indices: White blood cells (WBC) including lymphocytes and neutrophils counts and the Neutrophils to Lymphocytes ratio (NLR), were statistically analyzed among the three groups of participants. An upward trend was found in WBC, neutrophils and lymphocytes counts, after 5 weeks and more of exercise along with chemotherapy. Group C counts rose by 13.3%, 12% and 22% respectively. This study found no statistically significant effect of PA on NLR after the training regime among all groups. The results of the study may increase awareness of the benefits of PA as an adjunctive treatment for the disease in these patients. Further research is needed to determine the optimal length and a larger sample size at multi-center settings.

Keywords: Physical Activity; Training; Chemotherapy; Immune System; NLR

Abbreviations:PA: Physical Activity; WBC: White Blood Cells; NLR: Neutrophils to Lymphocytes Ratio; G-CSF: Granulocyte Colony Stimulating Factor

Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of death globally among men and women [1]. The 5-year survival rate is about 70% [2]. Regular exercising by cancer patients helps counteract the adverse effects associated with treatments [3,4]. 60-75 minutes per day of moderate-intensity activity may decrease the risk of mortality [2]. Additional benefits of physical activity (PA) during cancer treatment have shown that it reduced fatigue, caused by the disease, radiation and chemotherapy [5-7]. Moreover, exercising improves quality of life, self-esteem, increases vigor, improves balance control, body control and weight control [8-12]. As well, it revamps appetite, reduces stress, anxiety and depression, and lowers risk of falls [7,13-15]. In addition, research has shown that exercise among cancer patients improves daily functioning, preserves bone mass, and strengthens muscles function that may be impaired by chemotherapy and steroids [10,15,16]. Furthermore, it increases chances of survival, enhances the ability to cope with pain, and improves body image and mood [13,16-20]. PA reduces risk of comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease [21-26].

Resistance training helps lessen the side effects associated with cancer treatment in addition to improved muscle strength and increased bone mass density [3,27,28]. Galvão et al. found that resistance training in prostate cancer patients treated with androgenic hormone reduction, raised levels of lymphocytes and neutrophils indices which indicate improved immune system response [29]. It has been suggested that training regulates and advances the immune system surveillance [30,31]. PA is a strategy postulated for the treatment of cancer through its enhancement of anti-tumor immune response. Exercise has immunostimulatory effects on the immune system in several stages of combating the tumor [30]. It is stipulated that exercise exert modulation of the immune system and may serve, as an adjunctive approach to properly activate the treatment of cancer. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) score is a parameter related to the inflammatory status of an individual. It was found to indicate the risk level of breast cancer and gastrointestinal cancer. NLR index can predict the prognosis of these diseases [32-34].

The normal range of NLR is from 1 to 3 [35]. A higher-thannormal ratio has been associated with mortality from malignancies and from heart failure [36]. An association between NLR and training intensity was found among cyclists [37]. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the effect of PA training - that combines muscle endurance, work on range of motions, coordination and agility - performed during chemotherapy, on patients’ immune system indices e.g. White blood cells (WBC), Neutrophils, lymphocytes and NLR scores. To explore the research hypothesis, assessment of the patients’ immune system following training exercise sessions was compared with their baseline scores. It is assumed that the average count of WBC, neutrophils and lymphocytes will increase between the beginning and the end of the PA training intervention program. Additionally, the study hypotheses that there will be an enhanced immune system response, expressed as a difference between NLR at the beginning of the intervention program and at the end of the intervention program.

Methods

This retrospective consecutive study was conducted from June 10, 2019 to November 11, 2019 at Barzilai Medical Center Oncology department in conjunction with the Physiotherapy Unit. One hundred and three participants diagnosed with various types of cancer, men and women from the south of the country, treated with chemotherapy in the oncology department were recruited to this study. Inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years and completing blood tests before and after the PA training program. Compliance was achieved with 62 participants. Exclusion criteria included missing a blood test and or training session. Participation in this PA intervention program was voluntary.

Intervention Program

Intervals of chemotherapy course administration determined the instructed training schedule. The PA intervention was implemented over three time periods, Group A: 1 to 4.5 weeks, Group B: 5 to 9 weeks and Group C: 12 to 19.5 weeks. There were no intervention programs of 10, 11 and 14-weeks duration. PA training frequency ranged between twice a week to once every two weeks. The patient exercised while in a sitting position receiving chemotherapy. Each workout lasted 15 minutes and consisted of exercises to develop muscle endurance, aerobic physical fitness, coordination, increased range of motion in the joints and agility in a low intensity adapted to the patients’ condition. The training was delivered by a qualified physical education teacher or physiotherapist from the hospital staff. Each participant was asked to perform these PA training exercises independently at home every day.

Laboratory Blood Tests

The assessments took place on 2 different dates throughout the intervention program - pre PA training and after completing the chemotherapy course, post PA intervention program. Blood tests counted immune indices: WBC, neutrophils and lymphocytes. In addition, the ratio between the numbers of neutrophils to lymphocytes was calculated.

Statistical Processing

The data processing included statistics calculations and statistical inference for testing the research hypotheses. The results of the pre and post PA intervention program served to analyze the mean of each index and T-statistics were used for comparing pre and post training exercise parameters. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

Adherence to Ethical Rules and Privacy Protection

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Barzilai Medical Center. The study is retrospective which contains data collected as part of the routine care and approved by the Helsinki Committee. All participants gave written informed consent.

Results

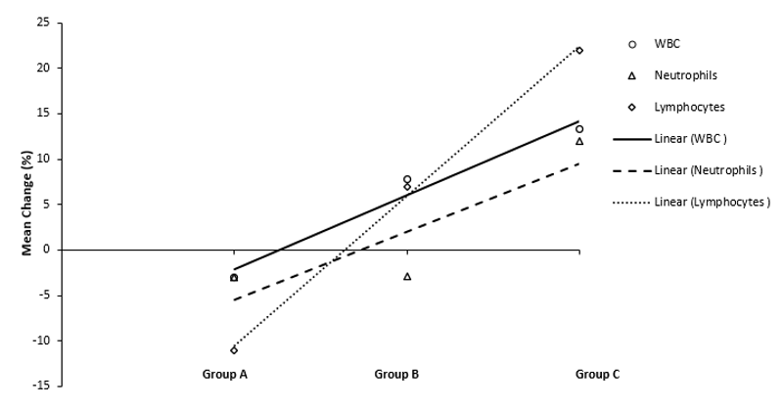

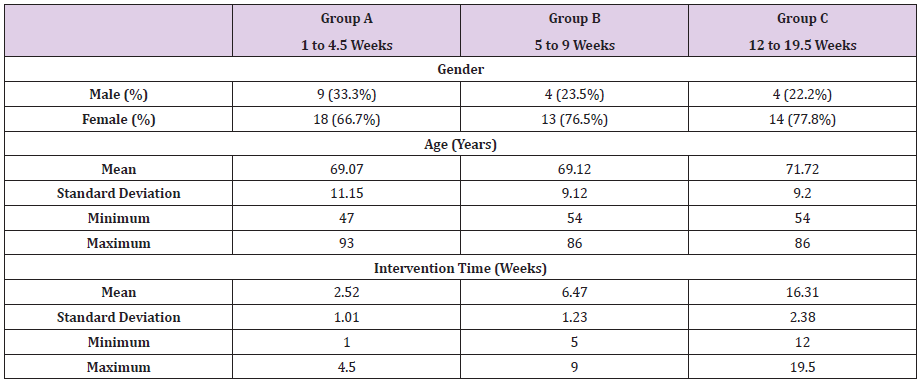

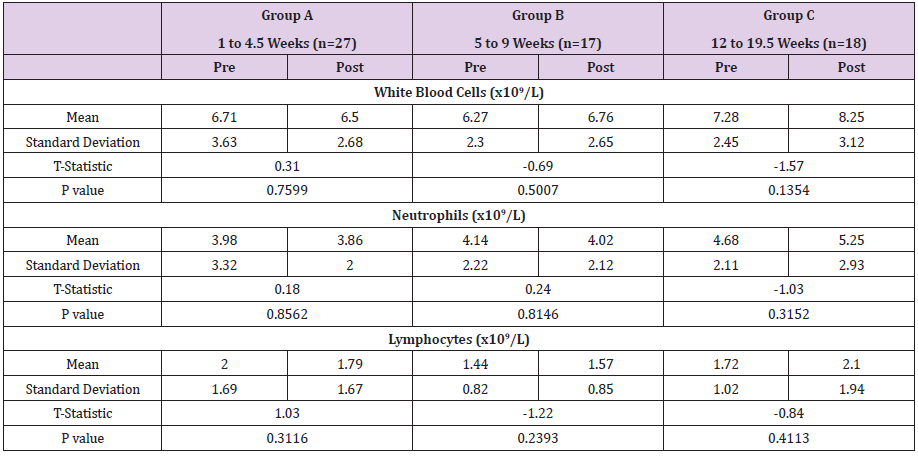

62 patients aged 47 to 93 years old were included and had their blood drawn pre and post- chemotherapy course. The study time period ranged from one week to 19.5 weeks. The number of participants in Group A, Group B, and Group C were 27, 17 and 18, respectively. Table 1 presents the study’s demographic characteristics. The mean age was 69.9 ± 9.99 years, and gender mean age was without statistical significance between females and males (69.1±10 years and 72.5±9.6 years, respectively). The mean age was similar among Group A, Group B and Group C. In each of the groups, most of the subjects were women. No statistically significant changes were found between the immune system indices when comparing pre and post PA intervention program (Appendix 1). In Group A, PA training intervention resulted in a decrease in all three indices: WBC, neutrophils and lymphocytes by 3%, 3% and 11% respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Trendline of mean change in immune system indices post training intervention program. The change in mean immune system indices: WBC, neutrophils and lymphocytes, post-training program presents the difference as percentage of the baseline preprogram counts. Trend lines were drawn using excel graphing program. Negative and positive change indicate decrease and increase, respectively; compared to pre PA mean counts. Group A exercised one to 4.5 weeks, Group B exercised 5 to 9 weeks and Group C exercised 12 to 19.5 weeks during their chemotherapy course.

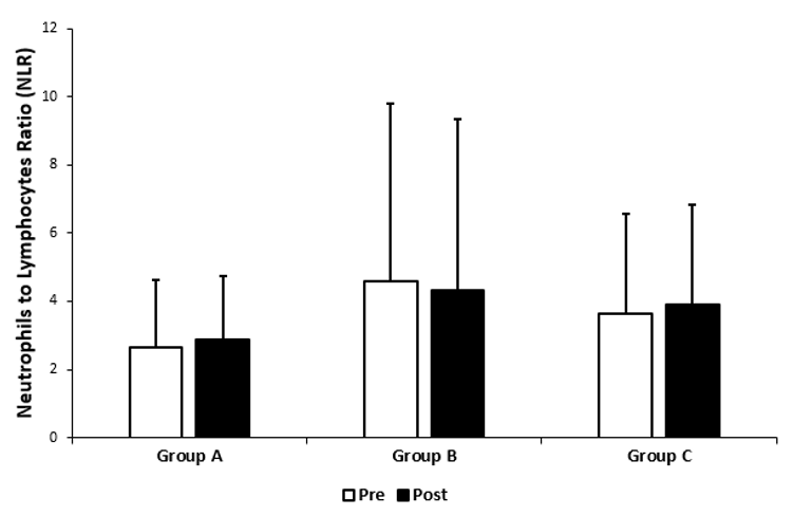

In Group B, a similar decrease in neutrophil values was observed (2.9%), however the number of WBC and lymphocytes increased by 7.8% and 6.9%, respectively. In Group C, PA training, increased further in each of the indices: WBC, neutrophils and lymphocytes, 13.3%, 12% and 22% respectively. Figure 1 shows that as the training period extended, the indices change rose. The upward trend line manifests that a longer period of PA exercise training time could give more noticeable results. No statistically significant change was found in mean NLR following the completion of PA intervention program (Figure 2) in all three participants groups. Group A and Group C exhibited an NLR increase of 9% and 7.4% respectively, while Group B revealed 5% NLR decrease. Group B and Group C NLR means, both pre and post intervention program, are considered higher than in the general healthy population.

Figure 2: Comparison of Neutrophils to Lymphocytes Ratio (NLR) index, pre and post exercise intervention program. Group A: 1 to 4.5 weeks, Group B: 5 to 9 weeks and Group C: 12 to 19.5 weeks. Data presented as mean + Standard Deviation.

Discussion

This is the first study examining the effect of physical training on cancer patients which is performed while administering chemotherapy. The study findings reinforce previous reports showing that PA benefits patients through an ascend of the immune system at the end of the training period, especially when the intervention period exceeds 12 weeks. In addition, the longer the training period the more effect it tends to have on the immune system indices, although not statistically significant. Therefore, an extended and a more intense mode of PA may have a greater impact on the immune system parameters.

Interpretation of WBC Neutrophils and Lymphocytes and NLR Indices

Regular physical activity augment aspects of immune competency, thus promoting anti-cancer effect in humans was reported for lymphocytes [29,38]. Indices of WBC, neutrophils and lymphocytes were used as indicators of the immune system functional abilities. Group A exercised the shortest session and exhibited a reduction of the immune indices. A low lymphocyte counts after exercise, was found to be a result of immune cells surveillance at the peripheral tissues [38]. All three indices increased at the end of the intervention program compared to its inception after lengthy PA and chemotherapy course in Group C. Exercise oncology field studies demonstrated that being active leads to natural killer cells mobilization into tumor lesions [38]. Thus, performing “exercise immunotherapy” mediated by these lymphocytes anti-tumor effect on neoplastic growth.

A pitfall of NLR could be due to an active hematologic disorder: Leukemia, cytotoxic chemotherapy, or granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) may affect cell counts [39].

Therefore, the biphasic response expressed as NLR over the time of training program could be attributed to medical status of the participating patients. In addition, the low sample size could be the cause for the high variability between individuals. The study participants consisted of older adults (mean age 70 years). Aging is typically associated with decrease in immune competence which presents as lower counts [38]. Hence the challenge to elicit an enhanced immune response in these individuals who are also burdened by cancer. Aging has been reported to be associated with an increase in neutrophil counts [38]. Apparently, this could be a partial probable explanation for high NLR presented in participants of Group B and C. However, the mean age of Group A participants was similar to Groups B, C (69.7 vs 69.12, 71.72 years, respectively) thus other factors could be responsible for the differences of high baseline counts pre-exercise in groups B, C such as individuals’ inherent medical condition.

Strengths and Limitations

The fact that the training was found to be safe and non-harmful to heterogeneous population of both females and males indicates that this strategy can be used to encourage cancer patients to exercise during chemotherapy. Other intervening factors may affect the patient’s body response that were beyond the scope of this study, such as cancer type, disease status, co-existing maladies and more. Self-exercising at home was not monitored which could be a possible reason for insignificant difference between the baseline pre and “post” exercise program results.

Future Research Directions

An extended period training program and at a moderate to higher intensity should be investigated as a trend to increase the physiological effect of the immune system on the body. In addition to absolute number counts, it is pertinent to further examine the immune cells functionality to gain insight and verify their active potential exerting conjunctive cytotoxic effect on tumor cells during chemotherapy course. Future directions will explore more detailed molecular mechanism involved in the body reaction to physical exercise while chemotherapy is administered, such as specific cytokines and inflammatory factors.

Conclusion

The implication of this research may suggest that PA should be encouraged, in particular to achieve exercise induced benefit on the immune potency of the oncological population and a change in their lifestyle [40]. As a result, all cancer patients are recommended to have physical exercise as part of the standard care guidelines instructed by the ministry of health authorities. In conclusion, a long-term training period may help strengthen the immune system and thus also in dealing with the disease, as the immune system has an important role in eliminating cancer cells [30].

Contributors

a) EC and NA have contributed equally to the research,

logistics and drafted the manuscript.

b) AA revised and wrote the final manuscript.

c) All authors approved the final version and affirm that

the manuscript is honest, accurate and transparent account of the

study being reported.

Competing Interests

All authors declare to have no competing interests.

Data Sharing

Data collected for the study, including deidentified individual participant data will be made available after publication. Requests on data sharing can be made by contacting the corresponding author. The lead author AA affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned, have been explained. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited an the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

References

- (2020) Cancer. World Health Organization.

- (2020) Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. American Cancer Society.

- Galvão DA, Nosaka K, Taaffe DR, Spry N, Kristjanson LJ, et al. (2006) Resistance training and reduction of treatment side effects in prostate cancer patients. Med Sci Sports Exerc 38(12): 2045-2052.

- Tello M (2018) Exercise as part of cancer treatment. Harvard Health Blog. Harvard Health Publishing: Harvard Medical School.

- (2020) Managing Fatigue or weakness. American Cancer Society.

- Zhang LL, Wang SZ, Chen HL, Yuan AZ (2016) Tai Chi Exercise for Cancer-Related Fatigue in Patients With Lung Cancer Undergoing Chemotherapy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pain Symptom Manag 51(3): 504-511.

- Singh B, Spence RR , Steele ML, Sandler CX, Peake JM, et al. (2018) A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Safety, Feasibility, and Effect of Exercise in Women With Stage II+ Breast Cancer. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 99(12): 2621-2636.

- Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Sela RA, Quinney HA, Rhodes RE, et al. (2003) The group psychotherapy and home‐based physical exercise (group‐hope) trial in cancer survivors: Physical fitness and quality of life outcomes. Psychooncology 12(4): 357-374.

- Awick EA, Siobhan MP, Gillian RL, Mc Auley E (2017) Physical Activity, Self-Efficacy and Self-Esteem in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Panel Model. Psychooncology 26(10): 1625-1631.

- Ax AK, Johansson B, Carlsson M, Nordin K, Börjeson S (2020) Exercise: A positive feature on functioning in daily life during cancer treatment - Experiences from the Phys-Can study. Eur J Oncol Nurs 44: 101713.

- Michael C (2016) Balance Exercises After Cancer Treatment. Cancer. Net Doctor-Approved Patient Information from ASCO. American Society of Clinical Oncology.

- Demark Wahnefried W, Rogers LQ, Alfano CM, Thomson CA, Courneya KS, et al. (2015) Practical clinical interventions for diet, physical activity, and weight control in cancer survivors. CA-Cancer J Clin 65(3): 167-189.

- Speca M, Carlson LE, Goodey E, Angen M (2000) A Randomized, Wait-List Controlled Clinical Trial: The Effect of a Mindfulness Meditation-Based Stress Reduction Program on Mood and Symptoms of Stress in Cancer Outpatients. Psychosom Med 62(5): 613-622.

- (2020) Balance Problems and falls. American Cancer Society.

- Winters Stone KM, Dobek J, Nail L, Bennett JA, Leo MC, et al. (2011) Strength training stops bone loss and builds muscle in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: a randomized, controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 127(2): 447-456.

- Wolin KY, Schwartz AL, Matthews CE, Courneya KS, Schmitz KH (2012) Implementing the exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. J Support Oncol 10(5): 171-177.

- Haines TP, Sinnamon P, Wetzig NG, Lehman M, Walpole E, et al. (2010) Multimodal exercise improves quality of life of women being treated for breast cancer, but at what cost? Randomized trial with economic evaluation. Breast Cancer Res Tr 124(1): 163-175.

- Speck RM, Gross CR, Hormes JM, Ahmed RL, Lytle LA, et al. (2010) Changes in the Body Image and Relationship Scale following a one-year strength training trial for breast cancer survivors with or at risk for lymphedema. Breast Cancer Res Tr 121(2): 421-430.

- (2012) Oregon State University, Improving confidence keeps breast cancer survivors exercising. Oncology & Cancer. Medical Xpress.

- Loprinzi PD, Cardinal BJ, Si Q, Bennett JA, Winters Stone KM (2012) Theory-based predictors of follow-up exercise behavior after a supervised exercise intervention in older breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 20(10): 2511-2521.

- De Souza VB, Silva EN, Ribeiro ML, Martins WA (2015) Hypertension in Patients with Cancer. Arq Bras Cardiol 104(3): 246-252.

- Collins KK (2014) The Diabetes-Cancer Link. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Spectr 27(4): 276-280.

- (2020) Diet and Physical Activity: What’s the Cancer Connection? American Cancer Society.

- Ellahham SH (2019) Exercise Before, During, and After Cancer Therapy. American College of Cardiology.

- Stefani L, Maffulli N, Mascherini G, Francini L, Petri C, et al. (2015) Exercise as Prescription Therapy: Benefits in Cancer and Hypertensive Patients. Transl Med UniSa 11: 39-43.

- D’Ascenzi F, Anselmi F, Fiorentini C, Mannucci R, Bonifazi M, et al. (2019) The benefits of exercise in cancer patients and the criteria for exercise prescription in cardio-oncology. Eur J Prev Cardiol.

- Sprod LK (2009) Considerations for Training Cancer Survivors. Strength Cond J 31(1): 39-47.

- Ferioli M, Zauli G, Martelli AM, Vitale M, Mc Cubrey JA, et al. (2018) Impact of physical exercise in cancer survivors during and after antineoplastic treatments. Oncotarget 9(17): 14005 -14034.

- Galvão DA, Nosaka K, Taaffe DR, Peake J, Spry N, et al. (2008) Endocrine and immune responses to resistance training in prostate cancer patients. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 11(2): 160-165.

- Koelwyn GJ, Wennerberg E, Demaria S, Jones LW (2015) Exercise in regulation of inflammation-immune axis function in cancer initiation and progression. Oncology (Williston Park, NY) 29(12): 908-920.

- Ashcraft KA, Warner AB, Jones LW, Dewhirst MW (2019) Exercise as Adjunct Therapy in Cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol 29(1): 16-24.

- Koh CH, Bhoo Pathy N, Ng KL, Jabir RS, Tan TH, et al. (2015) Utility of pre-treatment neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio as prognostic factors in breast cancer. Br J Cancer 113(1): 150-158.

- Ramos-Esquivel A , Rodriguez Porras L, Porras J (2017) Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio as prognostic factors in non-metastatic breast cancer patients from a Hispanic population. Breast Dis 37(1): 1-6.

- Ramos Esquivel A, Cordero García E, Brenes Redondo D (2018) The Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio Is an Independent Prognostic Factor for Overall Survival in Hispanic Patients with Gastric Adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Cancer 50: 728-734.

- Forget P, Khalifa C, Defour JP, Latinne D, Pel MC, et al. (2017) What is the normal value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio? BMC Res Notes 10(1): 12.

- Benites Zapata VA, Hernandez AV, Nagarajan V, Cauthen CA, Starling RC, et al. (2015) Usefulness of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in risk stratification of patients with advanced heart failure. Am Journal Cardiol 115(1): 57-61.

- Azam M, Setyaningsih E, Rahayu SR, Fibriana AI, Setianto B, et al. (2019) Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and exercise intensity are associated with cardiac-troponin levels after prolonged cycling: the Indonesian North Coast and Tour de Borobudur 2017 Troponin Study. J Sport Health Sci 15: 585-593.

- Campbell JP, Turner JE (2018) Debunking the Myth of Exercise-Induced Immune Suppression: Redefining the Impact of Exercise on Immunological Health Across the Lifespan. Front Immunol 9: 648.

- Farkas J (2019) PulmCrit: Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR): Free upgrade to your WBC.

- Kampshoff CS, Chinapaw MJ, Brug J, Twisk JWR, Schep G, et al. (2015) Randomized controlled trial of the effects of high intensity and low-to-moderate intensity exercise on physical fitness and fatigue in cancer survivors: results of the Resistance and Endurance exercise After ChemoTherapy (REACT) study. BMC Med 13(1): 275.

Research Article

Research Article