Abstract

Broiler chickens are intensively selected for productive traits. The management of these highly productive animals must be optimal to allow their full genetic potential to be expressed. Ascites is the accumulation of non-infectious fluid in the peritoneal cavity and it is a metabolic disorder resulting in considerable economic loss in the broiler industry fast-growing chickens. The study was conducted from December 2019 to February 2020 in Bishoftu town, Oromia regional state. A cohort study design method was used to collect data from 100 randomly selected fast-growing chickens strain (COBB500) kept in the dip litter management system in Alema commercial poultry farm at Bishoftu Town, to assess the effect of age, weight, temperature, and ventilation on the development of ascites. Blood samples were collected every week (started from week 3) and hematology (packed cell volume) was determined, this parameter is elevated in chicken suffering from the syndrome. Accordingly, It was found that factors such as age and weight caused a rapid and significant rise in packed cell volume, increasing relative humidity was shown little change in the packed cell volume, and the medium temperature did not cause ascites. The incidence of the ascitic syndrome and its economic effect can be reduced by slowing the growth rate and good environmental management.

Keywords: Age; Ascites; Broiler; Humidity; Ventilation; Weight

Introduction

Ethiopia is one of the developing countries in Africa, with over

85% of its population engaged in agricultural activity [1]. It is

endowed with many livestock species with an estimated population

of 56.7 million cattle, 29.33 million sheep, 29.11 million goats, and

56.87 million poultry production [2], from which native chicken

representing 96.9%, hybrid chicken 0.54% and exotic breeds 2.56%

[3]. Chicken can be reared in different management and production

systems. Based on chicken breed type, input and output level,

type of producer, the purpose of production, length of broodiness,

growth rate, and the number of chickens reared, in Ethiopia, there

are three types of chicken production systems including free-range,

semi-intensive, and intensive production systems [4]. There are few

farms in the commercial subsectors and they have varying flock

sizes [5]. Almost every rural family in Ethiopia rear chickens which

provide a valuable source of protein and family income [2]. Even

though chickens are often been described as a source of protein

and family income animals they succumb to a variety of diseases

and several other unhealthy circumstances [6]. Broiler chickens

are intensively selected for productive traits. The management of

these highly productive animals must be optimal to allow their

full genetic potential to be expressed. If this is not done, inefficient

production and several metabolic diseases such as ascites become

apparent [7].

Ascites also called Pulmonary hypertension syndrome or

Waterbelly, is the accumulation of non-infectious transudates in the

peritoneal cavity and classified as a metabolic disorder resulting in considerable mortality (about 5%) and occurs usually in fastgrowing

chickens [8]. Genetic, environmental, and management

factors all seem to interact to produce ascites syndrome [9]. Modern

broilers have been intensively selected for improved feed efficiency

coupled with high growth rates; therefore, they require more oxygen

to sustain the rapid growth rate [10,11]. When sufficient oxygen is

not supplied, the heart rate increases to supply more oxygen to the

tissues, increasing blood flow, and pulmonary hypertension [9].

This causes a metabolic disorder known as ascites syndrome. The

syndrome is an important cause of mortality in the broiler industry

worldwide [11]. Despite the huge numbers of poultry population

and the increasing importance of broiler chickens in the Ethiopian

economy, there is no enough research relating to the assessment

of the effect of age, weight, temperature, and ventilation on the

development of Ascites has been conducted. Apart from a few

studies in other parts of Ethiopia, there have not been enough

reports on the effect of age, weight, temperature, and ventilation

on the development of ascites in Bishoftu. Therefore, the objective

of the study was to evaluate the effect of age, weight, temperature,

and ventilation on the development of ascites in broiler chickens.

Review on Ascites in Poultry Production

Ascites defined as the accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity or so-called “Waterbelly”. The disease is more scientifically known as pulmonary hypertension syndrome. Thus, Ascites is defined as an accumulation of non-inflammatory fluid in one or more of the abdominal spaces [12]. There may be clots of yellow material in the fluid. Ascites caused by right ventricular failure (RVF) have been observed worldwide in fast-growing broilers [13]. The ascites syndrome in broiler flocks has been increasing at an alarming rate, and this condition has become one of the leading causes of mortality and whole carcass condemnations throughout the world. Ascites represent a spectrum of physiological and metabolic changes leading to the excess accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity. These changes occur in response to several dietary, environmental, and genetic factors [10]. Ascites is most commonly diagnosed at 4-5 weeks of age. Total mortality due to ascites is higher in the male parent lines, which have the capability of faster growth and higher muscle deposition compared to the female lines [14].

Causes and Predisposing Factors of Ascites

Etiology: Ascites is a disease of broiler chickens occurring worldwide but especially at high altitude. The disease has a complex etiology and is predisposed by reduced ventilation, high altitude, and respiratory disease. Ascites is caused by the interaction between physiological (oxygen demand), environmental (altitude), management (poor ventilation and disease status) factors, genetics of the birds and may be related to the type of stock and strain [15]. Moreover, the combination of environmental (ambient temperatures, high altitudes, stock density, air quality), nutritional (diet density, feeding type), hygienic (feed, environmental hygiene), and genetic events leading to this metabolic disease [16,17]. Pulmonary arterial vasoconstriction appears to be the main mechanism of the condition. The morbidity rate is usually 1-5%, whereas the mortality is 1-2% but can increase up to 30% at high altitude [13,16]. The primary cause of ascites in meat-type chickens is right ventricular failure (RVF) as a result of increased pulmonary (lung) arterial pressure. The causes of insufficient oxygen supply and subsequent development of ascites in broilers are complex [12]. A considerable number of ascites syndrome in broiler flocks is caused by different types of microorganisms. Most of the Gramnegative bacteria (E. coli, Salmonella species, Campylobacter) are considered pathogenic because of their lipopolysaccharide (LPS) layer. Some studies have shown that LPS triggers pulmonary vasoconstriction leading to ascites (pulmonary hypertension) in broilers [18].

Airborne LPS is ubiquitous in the environment of broilers and is positively related to the amount of organic dust in poultry houses [19]. For example, respiratory exposure to E. coli can amplify the incidence of ascites five-fold in broilers. It is known that Salmonella typhiumurium may cause up to 79% mortality in one-week-old chickens. However, in some studies, lesions of salmonellosis were reported for 4 to 6-week old broilers with E. coli co-infection consequentially leading to ascites [20]. Another pathogenic agent is a mould, Aspergillus fumigates, occasionally present in the environment of all poultry. The disease caused by this mould, socalled “brooder pneumonia”, forms mould colonies in the lungs, and produces hard nodular areas leading to air sac infection and subsequently to the development of ascites [21].

Predisposing Factors: There may be many predisposing factors but ultimately the final cause leading to ascites is a deficiency of oxygen. Predisposing factors that increase the amount of oxygen required, reduce the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood, increase blood volume or interfere with blood flow through the lung may result in flock outbreaks of ascites [22]. The most important cause of increased work for the heart at low altitude appears to be the high oxygen requirement of rapid growth in modern broilers, combined with restricted space for blood flow through the small blood vessels of the lung [23,24].

Genetics and Ascites: Genetically, modern broilers with faster growth rates are more likely to develop Ascites due to the increased oxygen demand [25]. This is probably due to extreme selection for either the growth rate or the feed conversion ratio, which puts high demands on the metabolic processes, and the oxygen demand or oxygen requirement is affected by genetic factors other than the growth rate. Birds selected both for low food conversion ratio (FCR) with low rates of heat production that were stimulated to a higher heat production by a low ambient temperature had difficulties in adapting to environmental changes [26]. It has also been shown that the highest incidence of ascites occurs in broilers that combined low FCR with a fast growth rate, whereas in broilers with either slower growth or higher FCR, the incidence of ascites was much lower. A low FCR in fast-growing birds was attributed to low values of heat production. Moreover, birds selected for a combination of both fast growth and low FCR had low pO2 and high pCO2 in venous blood at low ambient temperature compared with the slower growing birds [7].

Growth Rate and Body Weight in Ascites: The broiler growth rate has been found to have a direct relationship with susceptibility to ascites [27]. Rapid growth and heavy body weight, particularly associated with a small skeletal frame, have been implicated in musculoskeletal and cardiovascular dis-ease in meat-type poultry. Rapid growth in a bird with insufficient pulmonary vascular capacity is the primary cause of PH, and when it is related to rapid growth it has been called pulmonary hypertension syndrome (PHS). The anatomy and physiology of the avian respiratory system are important in the susceptibility of meat-type chickens to PHS [28]. The small structure of the modern meat-type chicken, the large, heavy breast mass, the pressure from abdominal contents on air sacs, and the small lung volume may all be involved in the increased incidence of PHS. The lungs of birds are smaller as a percentage of body weight than those of mammals and the lungs of birds are also firm and fixed in the thoracic cavity. They do not expand and contract with each breath as mammalian lungs do. The blood and air capillaries form a network that allows the small blood capillaries of the lung to dilate only very little to accommodate increased blood flow [13,25].

Nutrition and Ascites: Manipulation of the diet composition and/or feed allocation system can have a major effect on the incidence of ascites [15]. In most instances, such changes to the feeding program influence ascites via their effect on the growth rate. Major nutritional factors including high nutrient density rations, high feed intake, and feed form are known to influence the occurrence of ascites in broilers [7].

Environmental/Management Factors and Ascites

A. Altitude

The most obvious environmental factor to play a role in ascites development in broilers is a high altitude [16]. The effect of high altitude (either natural or simulated) is a decrease in the partial pressure of oxygen. When birds are exposed to low atmospheric oxygen levels (high altitude), pulmonary blood vessels constrict, and pulmonary vascular resistance increases. This immediate increase in pulmonary arterial pressure can, over time, cause right ventricular hypertrophy and eventually result in ascites syndrome [29].

B. Temperature

The second most studied environmental cause of pulmonary hypertension and ascites is temperature. Cold temperatures increase ascites by increasing both metabolic oxygen requirements and by increasing pulmonary hypertension attributed to this increase in pulmonary arterial pressure to a cold-induced increase in cardiac output, as opposed to being caused by hypoxemic pulmonary vasoconstriction [13]. The effect of the timing of cold stress on ascites development in broilers indicates that exposure to cold temperatures during brooding has a lasting effect on ascites incidence [30].

C. Lighting

Broilers are usually grown on a near-continuous lighting schedule, so that feed consumption and growth rate can be maximized. Early studies in photoperiod manipulation reported a decreased growth rate for broilers raised with a step-down lighting program. It was hypothesized that limiting the number of hours of light will slow growth slightly and will reduce activity that requires additional oxygen and may improve feed efficiency. Subsequent studies on the effect of longer dark periods or intermittent lighting indicated that similar to feed restriction [15].

D. Air quality and ventilation

It has been suggested that poor ventilation could cause low environmental oxygen or high toxic fumes (carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, or ammonia), which may have detrimental effects on the respiratory or cardiovascular systems of birds and promote ascites development. It also has been suggested that environmental dust could affect oxygen transfer in the lung and increase the ascites incidence [7]. The hypothetical effects of air quality and ventilation have been difficult to prove. Although birds exposed to poorly ventilated conditions have been reported to develop greater numbers of cartilaginous and osseous nodules in their lungs and birds with ascites syndrome have higher numbers of these nodules and the causal effect of low ventilation on ascites is still unproven [31].

Incubation and Ascites

It has already been mentioned that an increased metabolic rate, paralleled with a shortage in oxygen supply, will lead to Ascites. One of the most demanding stages of chicken development is in the incubator. Chickens incubated at high altitudes may be predisposed to Ascites because the partial pressure of oxygen is lower. It is therefore important that adequate ventilation in the incubator is achieved. Achieving adequate ventilation may be a particular issue in single-stage machines; in the setter, the air vents should be left fully opened for the last 3 days to ensure that ventilation, and thus oxygen levels, are optimal [24,32].

Association between Hematocrit Values (PCV) and Ascites

A significant increase in hematocrit values is a common phenomenon in most ascites cases in broilers [33]. The higher hematocrit values indicate increased blood viscosity and high blood viscosity considers the primary or main factor causing ascites at high altitude [30]. PCV value in ascetic broilers increased as a result of an increase in the number of erythrocytes, and enhanced erythropoiesis and not plasma volume reduction was found to be involved in the hemodynamics of ascetic broilers. The first reaction of the body to oxygen deficiency is an increase in the heart rate, with prolonged exposure to anoxia the number of erythrocytes increases leading to increased hematocrit value [33,34].

Pathogenesis

Bird lungs are rigid and fixed in the thoracic cavity. The capillaries can expand very little to accommodate increased blood flow. Lung size in proportion to body weight, and particularly to muscle mass, decreases as meat-type chickens grow. Increased blood flow results in primary pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale with sporadic cases of RVF and ascites in fast-growing broilers. Predisposing factors that increase oxygen demand (eg, cold), reduce the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood (eg, acidosis, carbon monoxide), increase blood volume (eg, sodium), or interfere with blood flow through the lung (eg, lung pathology that narrows or occludes capillaries, increased RBC rigidity, or polycythemia with increased blood viscosity) may result in flock outbreaks of pulmonary hypertension syndrome with or without ascites [13,16]. Pulmonary hypertension syndrome is caused by increased pressure in the pulmonary arteries when the heart tries to pump more blood through the lungs to meet the body’s oxygen requirement. The resultant volume and pressure overload on the right ventricle cause dilatation and hypertrophy of the right ventricular wall, valvular insufficiency, RVF, and ascites [17]. The incidence of pulmonary hypertension syndrome is >2% in some broiler and many roaster flocks and is occasionally 15%-20% in other roaster flocks. Right ventricular hypertrophy is the response to an increased workload and eventually leads to RVF if the volume or pressure load persists. Hypertrophy and dilatation of the right ventricular wall are directly related to pulmonary hypertension, and the ratio of the right ventricle to the total ventricular mass can be used as a measure of the increased pressure load on the right ventricle [10,22].

Clinical Findings and Diagnosis

Occasionally, young broilers develop pulmonary hypertension syndrome, particularly if increased sodium or lung pathology (eg, Aspergillosis) is involved, but mortality is greatest after 5 wk of age. There are no signs until RVF occurs and ascites develop. Clinically, affected broilers are cyanotic, the abdominal skin may be red, and peripheral vessels congested. Because growth stops as RVF develops, affected broilers may be smaller than their pen mates. However, the rapid growth rate is a known predisposing factor, and sometimes the largest broilers are affected, with occurrence in males more frequently than in females [16]. Ascites increases the respiratory rate and reduces exercise tolerance. Affected broilers frequently die on their backs. Not all broilers that die from pulmonary hypertension syndrome have ascites. Death may occur suddenly before signs are seen [18,23]. Most lesions are the result of increased venous hydraulic pressure secondary to RVF. There is a variable amount of clear yellow fluid and clots of fibrin in the hepatoperitoneal spaces. The liver may be swollen and congested, or firm and irregular with edema, and have clotted protein adherent to the surface. It may be nodular or shrunken; it may be white with subcapsular edema and a thickened capsule or have large or small blebs of fluid between the capsule and the visceral peritoneum [13].

Hydropericardium is mild to marked, and occasionally there is pericarditis with adhesions, usually from secondary infections. Right ventricular dilatation and mild to marked hypertrophy of the right ventricular wall may be noted. The right atrium and vena cava are markedly dilated in most cases. Occasionally, there is thinning of the left ventricle. The lungs are extremely congested and edematous. The intestine may or may not be empty [35]. Any factors that increase the workload of the heart by increasing the oxygen demand (e.g. fast growth, reduced environmental temperatures, and low partial pressure of oxygen or respiratory diseases) can lead to Ascites. When the workload on the heart and lungs is increased, a chain of events is triggered that leads to reduced levels of oxygen in the blood [17,36]. The lungs of chickens are rigid and molded into the thoracic cavity and they cannot expand like mammalian lungs. The capillaries can expand only a little to allow for increased blood flow. The lungs of chickens grow less rapidly than the rest of the body, and lung capacity does not keep up with the very rapid growth of muscle in fast-growing broiler chickens. In addition to high oxygen demands associated with their fast growth rate, the fast metabolism of the modern broiler chicken increases the production of reactive oxygen types that increase oxidative stress, causing damages to pulmonary vessels [23] (Figure 1).

The lack of oxygen causes a marked increase in the number of red blood cells that makes the blood more viscid and difficult to pump through the lung, causing pulmonary hypertension (PH). When the oxygen supply is insufficient, the heart must circulate blood more rapidly to provide the same amount of oxygen to the body. The right side of the heart enlarges in response to the increased workload and, if the heart has to continue working harder than normal, the result is right ventricular valve insufficiency, volume overload, right ventricular dilatation, and RVF. As a result, venous blood pressure increases, and fluid leaks out of the veins and accumulates in peritoneal cavities, resulting in ascites [17,23,37]. Upon diagnosis of ascites, broilers that die from ascites or suddenly as the result of RVF or pulmonary hypertension can be identified by the enlarged heart; enlarged, thickened right ventricle; or fluid in the body cavities and heart sac. If the wall of the right ventricle is enlarged or thickened, the broiler has probably died from pulmonary hypertension syndrome, even if there is no fluid in the body or heart sac [12,16,23].

Ascites Symptoms

The most common signs of ascites in broilers are sudden deaths in rapidly developing birds, poor development, abdominal distension (“Waterbelly”), progressive weakness, recumbency, birds have trouble breathing and often just sit and pant (dyspnea), poor bird development, dilated abdomen (water belly), sometimes their flesh tends to look bluish (cyanosis) because of inadequate oxygen in the blood, and sudden deaths in rapidly developing chickens [12,16,28].

Post-Mortem Examination and Diagnosis

At post-mortem, there is a large or small quantity of clear yellow fluid and clots of fibrin in the abdomen. The liver may be swollen and congested, or firm and irregular with edema (fluid), and have fibrin adherent to the surface [12]. Not all broilers that die from RVF have ascites. Death may occur before clinical signs are observed, and affected broilers frequently die on their back. At necropsy, there may be a swollen liver, venous congestion, a dilated right atrium and vena cava, and thickening of the right heart, as well as marked lung congestion and edema (death is likely from respiratory failure). The intestine may or may not be empty, but the heart changes will differentiate RVF from flip-over [35].

Treatment and Prevention of ascites

Firstly, it is important to understand the underlying causes of an ascites occurrence on a poultry farm. In the case of ascites caused by genetics, feed restriction might reduce the effect of the disease. Slower growing birds have reduced oxygen needs allowing the cardiopulmonary organs (heart and lungs) to keep up with oxygen demands of the birds. However, reducing the feed intake of broilers decreases growth performance. Feed restriction is only of economic benefit when the incidence of ascites is very severe [11,13]. In the case of ascites caused by microorganisms, recent studies investigating the effect of feed supplementation with acidifiers have shown promising results. Of course, optimal management practices are also very important for reducing the problem of ascites and maximizing the performance of broilers [15]. In general, slowing growth to reduce the oxygen required after 30-35 days of age can prevent ascites caused by primary pulmonary hypertension. Restricting feed, feeding a mash diet, using a less energy-dense diet, or decreasing daylight hours in the barn could accomplish this [23]. Control environmental temperature, litter moisture, humidity, and air quality to prevent excessive body heat loss and to maintain bird health. Monitor sodium levels in feed and water to prevent salt intoxication. Altitudes above 900 m are inadequate for meat-type chickens, and growth must be slowed to prevent mortality [24,38].

Materials and Methods

Description of Study Area

The study was conducted from December 2019 to February 2020 in Bishoftu town, Oromia regional state. Bishoftu is located 47.9 km southeast of the capital city Addis Ababa. The area is located at 90 N latitude and 400 E longitude. The altitude is about 1850 meters above sea level. The average annual rainfall is 866 mm with a bimodal distribution. The long rainy season extends from June to September (with 84% of the rain) followed by a dry season from October to February. The short rainy season lasts from March to May. The mean annual minimum and maximum temperatures are 17.40C and 20.40C, respectively. The mean relative humidity is 61.3% [39]. In Ada`a Liben district where Bishoftu is the center, there are about 160, 697cattles, 22,181sheep, 37, 510 goats, 5, 660 horses, 38, 726 donkeys, 268, Mules, 191, 380 poultry and 3, 274 beehives [40].

Study Animals

A. Chickens: Seven-thousand-five-hundred two broilers of the COBB-500 breed were received on the day of the hatch in the late December at Alema commercial broiler farm in Bishoftu town, from which the study was conducted on 100 chickens. This breed is fast-growing and, as such, susceptible to the ascites syndrome.

B. Housing: Birds were distributed randomly, throughout the floor pens, to achieve a density of 10-13 birds/m2 and the housing system used in this farm was a dip litter system. The ambient temperature was thermostatically controlled, and Relative humidity was determined by recording hygrometers placed in the house. Up to the age of 10 days, the houses were not ventilated, the opening of the window and roof was closed by a plastic cover, and brooders were remained within the house until 10 days to maintain a good temperature for chickens and it will be removed after 11 days. On this farm ventilation was carried out by natural method, the inlet is from the windows (made up of mesh) and outlet is from the roof (open roof), after 10 days all covering plastics of window and roof was removed, as the air needed.

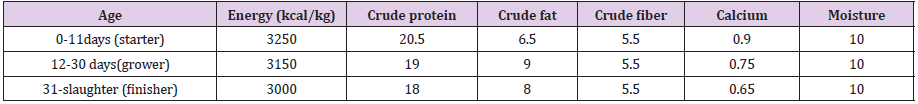

C. Feed: Feed and water were provided ad libitum. All chickens were given timely and adequate vaccination against common poultry viral disease. The birds were fed a starter diet for the first 11 days, and grower diet for the next 18 days and finally feed finisher diet until slaughtering day (Table 1).

Study Design

A cohort study design method was used to collect data from chicken managed under the dip litter management system. The assessment was carried out in Alema commercial poultry farm at Bishoftu Town to determine the effect of age, weight, temperature, and ventilation on the development of ascites.

Sampling Technique and Sample Size

A random sampling technique was employed to select 100 chickens to determine the effect of age, weight, temperature, and ventilation on the development of ascites.

Study Methodology

All 100 sampled chickens were marked to differentiate from the rest flock and kept with the others in the same management system and house. Before collecting any sample (weight and blood) all marked chickens were selected and collected in one group, in the first two weeks only weight was taken by sensitive weighting balance because it was so difficult to taken blood samples from the wing vein, it was very thin. After the third week, all sampled chickens were weight and a blood sample was taken from 20 chickens in every week until the last week. After sampling, marked chickens were returned to the flock.

Laboratory technique

Blood sample for analysis was collected early in the morning from 20 randomly sampled chickens on day 15, 22, 29, 36 and 43 in every week directly from the wing vein of each chickens using a sterile needle, then the blood is collected into EDTA (anticoagulant blood) collection tube. During the collection of blood needles and syringes were changed between birds to prevent contamination and not more than 2ml blood was taken per bird in a day. Finally, the collected sample was transported to the laboratory and all collected blood samples were clearly labeled with the date of sampling and age of the chickens. Hematology (PCV) was performed in a pathology laboratory to determine packed cell volume following standard procedures described by (Jelalu, 2014) and expressed as a percentage. To obtain the PCV, Anticoagulated blood sample was filled into heparinized capillary tubes to the three-quarter level and then sealed at one end using a sealant. The sealed capillary tubes were centrifuged at 15,000 revolutions per minute for 3 minutes. Thereafter the sedimented blood cells were read using the microhematocrit reader.

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

All collected data were recorded, coded, and entered in Microsoft Excel worksheet and were analyzed using STATA version 13 computer software. The data summarized using descriptive statistics and all values were expressed in as Means ± Standard deviation of the mean.

Results

Effect of Age and Weight

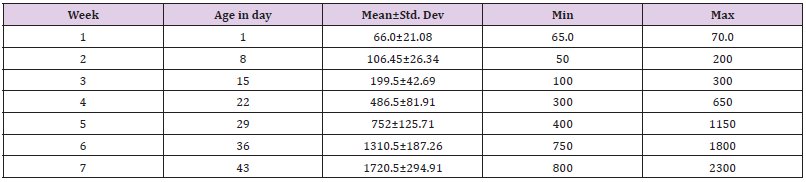

The weight of chickens increases every week. When started from the second week, the chicken increases their weight gain almost twice from the first weight on the first day of (66.0±21.0) in the first week. Besides, the increment was seen in the following weeks with a mean of (106.45±26.34) in the second week, (199.5±42.69) in the third week, (486.5±81.91) in the fourth week, (752±125.71) in the fifth week, (1310.5±187.26) in the sixth week and (1720.5±294.9) in last week. The weight of the chicken increase corresponding to their age, when the weight gain increases the body temperature and metabolic rate of the chicken also increase (Table 2).

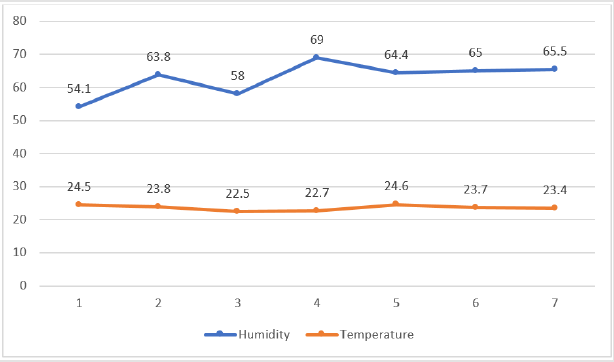

Effect of humidity

For the first week humidity of the house was in average varied between (54.1 and 63.8), (63.8 and 58) in the second week, (58 and 69) in the third week, (69 and 64.4) in the fourth week, (44.4 and 65) in the fifth week, and (65 and 65.5) in last sixth week. In week second and the last four weeks (week 4, 5, 6 and 7) the humidity of the house was increased, at this time the air quality of the house was poor it was made discomfort when entering the house, in addition to this the bedding was unacceptably wet and the litter was added to reduce the bedding wet, it was decided to start ventilating the House through natural ventilation by removing covering plastics of window drag to the bottom (Figure 2).

Effect of Temperature

The daily temperature recorded in the house varied from 16.8- 33.6°C (first week), 18.4-29.4°C (second week), 16.2-29.9°C (third week), 16.3-29.6°C (fourth week), 19-32°C (fifth week), 15.9- 29.7°C (sixth week) and 17.4-21.4°C (week seven) with a mean of 24.5°C, 23.8°C, 22.5°C, 22.7°C, 24.6°C, 23.7°C and 23.4°C in every week, respectively (Figure 2). The maximum daily temperature was between 19 and 32°C with a mean of 24.6°C. There was a brooder for the first 10 days in the house to maintain a good temperature for chickens. The temperature of the chickens was increased with their age and all covering plastics of windows and roofs were removed, and the room was ventilated by natural ventilation.

Comparison of Packed cell volume over the weeks

As indicated in Table 3, there was variation in the PCV among

chickens between weeks 3 and 7. For the duration of development,

PCV was increased every week, the highest level of packed cell

volume (PCV) in the birds was at week 7 (35.88 ± 2.71) which

was significantly higher than the week 6 (33.03±4.05), week 5

(29.60±2.54), and week 4 (27.25±1.89) values. The PCV value of the chickens at week 3 (25.93±3.29) was significantly less than other

weeks on the study duration. Every week started from week 3 (day

21), nearly all the chickens showed a rise in PCV with their age even

if it was under normal range (only week 4 and 5 chickens had PCV

value in the normal range). The correlation of the hematological

parameter (PCV) with the weight of birds indicated that chicken

PCV significantly correlated with their weight (Table 3). The present

study was conducted mainly to investigate the effect of age, weight,

and two environmental variables, humidity, and temperature on

ascites, the development of which were followed by monitoring

PCV. The basic aim of the study was to assess the causes of ascites

in broilers in Bishoftu and so provide a basis for developing logical

procedures to avoid and treat outbreaks of the syndrome.

The result presented showed that as the chickens grew older,

hematological value (PCV) increased with age. To assess the trend of

growth in chickens and other animals, body weight gain is normally

used because it indicates if the chicken is growing or not. In this study

body weight increased with age. There was a significant increase in

weight difference in all the weeks in ascending order from week 1 to

7, meaning that they gained more weight as they grew. This agreed

with the report of [37]. The observed body weight gain of chickens

maybe as a result of proper utilization of protein, energy, vitamin,

and mineral components of their diet. At high temperature, air can

hold more water molecules and its relative humidity decrease. In

this study it was attempted, by providing good ventilation, to obtain

oxygen concentrations that would not constitute hypoxia. When the

temperature becomes decrease the relative humidity in the poultry

house was high or increase, the increasingly wet litter was proving

unacceptable and ammonia concentrations were high. Therefore, it

can be concluded that at least under Alema conditions of broiler

management, increasing relative humidity with the weight of

chicken had a role in predisposing or inducing to ascites.

The second most studied environmental cause of pulmonary

hypertension and ascites is temperature. Cold temperatures

increase ascites by increasing both metabolic oxygen requirements

and by increasing pulmonary hypertension attributed to this

increase in pulmonary arterial pressure to a cold-induced increase

in cardiac output, as opposed to being caused by hypoxemic

pulmonary vasoconstriction [13]. The temperature has a profound

and highly significant effect on the etiology and morbidity of ascites

incidence. But in this study chickens kept in the given (natural

temperature) at the regular system in that time when conducted

the study (late December-first February) had poor or no correlation

with PCV value of chickens because the temperature was not cold.

Therefore, it can be concluded that medium temperature has

no significant effect on inducing ascites. The packed cell volume

increased as the age of chicken increased. Although PCV is derived

from red blood cells, this agreed with the report of [33]. PCV value in

ascetic broilers increased as a result of an increase in the number of

erythrocytes, and enhanced erythropoiesis and not plasma volume

reduction was found to be involved in the hemodynamics of ascetic

broilers. The first reaction of the body to oxygen deficiency is an

increase in the heart rate, with prolonged exposure to anoxia the

number of erythrocytes increases leading to increased hematocrit

value. On the comparative study of hematological values of broiler

strain. PCV values obtained were within the physiological range

of 22-48% as stated by [34,41]. PCV range of 22-32% occurred at

weeks 3, 4, and 5, and 32-48% at week 6 and 7 indicated that PCV

values were high when the chickens are advanced in age.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Nowadays ascites syndrome occurs usually in fast-growing chickens, and it becomes economically important by resulting in considerable mortality (about 5%), in commercial broiler poultry farms. In this study, age, weight, and humidity factors all seem to interact to induce ascites syndrome by increasing metabolic rate and which leads to a rise in PCV. The reduction of rapid growth and management of environmental factors are an important component of commercial poultry farm profitability by reduced the loss of chickens due to ascites syndrome. It was found that factors such as age, weight, and high relative humidity are responsible for induced ascites but the medium temperature does not cause induced ascites. Because of the complex nature poultry production system and sensitivity of chickens (especially exotic breeds) for disease, chickens are easily prone to factors that induce ascites. Overall environmental management in general and their rapid growth rate are the major factors in the survival of the chickens. In conclusion, minimizing the growth rate of chickens by restricting feed, feeding less energy-dense diet, and by reducing daylight hours. Besides, improve the air quality or humidity of the poultry house by proper ventilation. Moreover, maintain the room temperature at an acceptable level.

References

- Getachew Y, Lemma A, Fesseha H (2020) Assessment on reproductive performance of crossbred dairy cows selected as recipient for embryo transfer in urban setup Bishoftu, Central Ethiopia. Int J Vet Sci Res6(1):080-086.

- Ebsa YA, Harpal S, Negia GG (2019) Challenges and chicken production status of poultry producers in Bishoftu, Ethiopia. Poultry science98(11):5452-5455.

- (2014) CSA. Central Statistical Agency, Agricultural Sample Survey 2 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Moges F, Dessie T (2010) Characterization of village chicken and egg marketing systems of Bure district, North-West Ethiopia. Livestock Research for Rural Development22(10).

- Wilson R (2010) Poultry production and performance in the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. World's Poultry Science Journal66(3):441-454.

- (2013) Food and Agriculture Organization. Poultry waste management in developing countries. Poultry development review: FAO, United Nations, Italy.

- Baghbanzadeh A, Decuypere E (2008) Ascites syndrome in broilers: physiological and nutritional perspectives. Avian pathology37(2):117-126.

- Jacob J (2015) Poultry Genetics For Small and Backyard Flocks: An Introduction. University of Kentucky.

- Namakparvar R, Shariatmadari F, Hossieni S (2014) Strain and sex effects on ascites development in commercial broiler chickens. Iranian Journal of Veterinary Research15(2):116-121.

- Afolayan M, Abeke F, Atanda A (2016) Ascites versus sudden death syndrome (SDS) in broiler chickens: A review. J Anim Prod Res28:76-87.

- Kamely M, Karimi Torshizi MA, Rahimi S (2015) Incidence of ascites syndrome and related hematological response in short-term feed-restricted broilers raised at low ambient temperature. Poultry science94(9):2247-2256.

- Milsavljevic T (2014) Ascites in Poultry. J Dairy Vet Anim Res1(2):18-20.

- Wideman R, Rhoads D, Erf G, Anthony N (2013) Pulmonary arterial hypertension (ascites syndrome) in broilers: a review. Poultry Science92(1):64-83.

- Dewil E, Buys N, Albers G, Decuypere E (1996) Different characteristics in chick embryos of two broiler lines differing in susceptibility to ascites. British Poultry Science37(5):1003-1013.

- Singh P, Shekhar P, Kumar K (2011) Nutritional and managemental control of ascites syndrome in poultry. International Journal of Livestock Production2(8):117-123.

- Nurmeiliasari N (2015) Ascites Incidence in Broilers. JurnalSainPeternakan Indonesia5(1):59-64.

- Olkowski A, Abbott J, Classen H (2005) Pathogenesis of ascites in broilers raised at low altitude: aetiological considerations based on echocardiographic findings. Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series A52(4):166-171.

- Chapman M, Wang W, Erf G, Wideman Jr R (2005) Pulmonary hypertensive responses of broilers to bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS): Evaluation of LPS source and dose, and impact of pre-existing pulmonary hypertension and cellulose micro-particle selection. Poultry science84(3):432-441.

- Bakutis B, Monstviliene E, Januskeviciene G (2004) Analyses of airborne contamination with bacteria, endotoxins and dust in livestock barns and poultry houses. Acta Veterinaria Brno73(2):283-289.

- Ganapathy K, Salamat M, Lee C, Johara M (2000) Concurrent occurrence of salmonellosis, colibacillosis and histomoniasis in a broiler flock fed with antibiotic-free commercial feed. Avian Pathology29(6):639-642.

- Urbaityte R (2019) Ascites in poultry. Mortality246(238.0):2066.

- Druyan S, Moschandreou T (2012) Ascites syndrome in broiler chickens-a physiological syndrome affected by red blood cells. book, Blood cell-an overview of studies in hematology: 243-270.

- Kalmar ID, Vanrompay D, Janssens GP (2013) Broiler ascites syndrome: collateral damage from efficient feed to meat conversion. The Veterinary Journal197(2):169-174.

- Aftab U, Khan A (2005) Strategies to alleviate the incidence of ascites in broilers: a review. Brazilian Journal of Poultry Science7(4):199-204.

- Currie RJ (1999) Ascites in poultry: recent investigations. Avian pathology28(4):313-326.

- Syafwan S, Kwakkel R, Verstegen H (2011) Heat stress and feeding strategies in meat-type chickens. World's Poultry Science Journal67(4):653-674.

- Camacho M, Suarez M, Herrera J, Cuca J, GarciaBojalilC (2004) Effect of age of feed restriction and microelement supplementation to control ascites on production and carcass characteristics of broilers. Poultry science83(4):526-532.

- Wideman R (2001) Pathophysiology of heart/lung disorders: pulmonary hypertension syndrome in broiler chickens. World's Poultry Science Journal57(3):289-307.

- Wang L, Fu G, Liu S, Li L, Zhao X (2019) Effects of oxygen levels and a Lactobacillus plantarum strain on mortality and immune response of chickens at high altitude. Scientific reports9(1):1-9.

- Julian RJ (2000) Physiological, management and environmental triggers of the ascites syndrome: A review. Avian pathology29(6):519-527.

- Balog JM (2003) Ascites syndrome (pulmonary hypertension syndrome) in broiler chickens: Are we seeing the light at the end of the tunnel? Avian and poultry biology reviews14(3):99-126.

- Azizian M, Rahimi S, Kamali M, KARIMI TM, Zobdeh M (2013) Comparison of the susceptibility of six male broiler hybrids to ascites by using hematological and pathological parameters. J Agr Sci Tech15:517-525.

- Islam M, Lucky N, Islam M, Ahad A, Das B, et al. (2004) Haematological parameters of Fayoumi, Assil and local chickens reared in Sylhet region in Bangladesh. Int J Poult Sci3(2):144-147.

- Goodwin MA, Davis JF, Brown J (1992) Packed cell volume reference intervals to aid in the diagnosis of anemia and polycythemia in young broiler chickens. Avian diseases: 440-443.

- Varga C, Taylor K (2013) Ascites syndrome in meat-type chickens. Report of the Canadian Ministry of Agriculture and Food, France.

- Nain S, Wojnarowicz C, Laarveld B, Olkowski A (2009) Vascular remodeling and its role in the pathogenesis of ascites in fast growing commercial broilers. Research in veterinary science86(3):479-484.

- Nyaulingo JM (2013) Effect of different management systems on haematological parameters in layer chickens: Sokoine University of Agriculture, East Africa.

- Kahn C (2005) The Merck Veterinary Manual 9th ed. White house station,Merck & COInc, USA.

- (2019) NMSA, National Meteorology Service Agency. Accessed on October 24/2019. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- (2003) Central Agricultural Census Commission. Ethiopian agricultural sample enumeration 2001/2002. Statistical Report on Farm Management Practices Livestock and Farm Implements Part II Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: 63-153.

- Goodwin M, Brown J, Davis J, Girshick T, Miller S, et al. (1992) Comparisons of packed cell volumes (PCVs) from so-called chicken anemia agent (CAA; a virus)-free broilers to PCVs from CAA-free specific-pathogen-free leghorns. Avian diseases: 1063-1066.

Research Article

Research Article