Abstract

Introduction: Postpartum women often confront their health care providers with complaints due to weakened abdominal wall muscles and diastasis recti. No reference values for young, healthy and nulligravidous women are present, which can serve as references for the diagnosis and treatment of complaints in postpartum women.

Study Purpose: Our study evaluated values for inter-rectal distance (IRD), thickness of the linea alba (LA), M. rectus abdominis (RA) and lateral abdominal wall muscles (LAWM) at different contraction states and levels along the abdominal wall for a cohort of young, healthy and nulligravidous women.

Materials and Methods: In a prospective cohort study from 4/2015-3/2016 we measured the dimensions of the abdominal wall muscles at different levels at rest and during Valsalva manoeuvre by ultrasound in 20 healthy, nulligravidous women aged 21-35 years. Exclusion criteria were a body mass index over 30 kg/m2, multiple or big uterine fibroids, chronic lung disorders, collagenosis, chronic constipation, history of urine/stool incontinence, former abdominal surgery and inability to perform Valsalva manoeuvre. Descriptive statistics were done for the study population and a one-way ANOVA for the muscle values, using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results: IRD is the widest at the umbilicus, wider above the umbilicus than below and decreases towards xyphoid and symphysis. The effect of rest and Valsalva manoeuvre on muscle thickness, IRD and LA is inconsistent and depends on the abdominal level and side. Valsalva manoeuvre thickens the RA and the two inner muscles of the LAWM, but not the outer muscle at almost every level. The values for RA and the LAWM are in average higher on the right body side.

Conclusion: By comparing individual values with our reference values, changes in the morphology of the abdominal wall in an individual can be detected and intervention strategies can be developed and controlled.

Keywords: Inter-Rectal Distance; Diastasis Recti; Abdominal Wall Muscles; M. Rectus Abdominis; Lateral Abdominal Wall Muscles

Abbreviations: IRD: Inter-Rectal Distance; LA: Linea Alba; RA: M. Rectus Abdominis; EO: M. Externus Abdominis; IO: M. Internus Abdominis; TrA: M. Transversus Abdominis ; LAWM: Lateral Abdominal Wall Muscles

Introduction

Postpartum women often confront their obstetricians, midwives, physiotherapists or even plastic surgeons with complaints due to weakened abdominal wall muscles and diastasis recti. No reference values for young, healthy and nulligravidous women are provided in the literature, which can serve as references for the diagnosis and treatment control of such complaints in that special group. It is well known, that the muscles of the abdominal wall play a major role in the stabilization of the trunk and the intraabdominal organs, in the movements of the whole body and in the biomechanics of respiration [1-9]. Weakened abdominal muscles and imbalance between the different structures might result in malfunction, pain or abnormal body shape [2,7,10-12]. The structures that mainly contribute to the integrity of the anterior and lateral abdominal wall are the M. rectus abdominis with the linea alba between the two portions of the muscle, the M. externus and internus obliquus abdominis and the M. transversus abdominis [1,3,10]. Their shape and function are affected by genetic factors, hormonal changes and specific conditions that cause a higher intraabdominal pressure, such as sports, obesity, constipation, chronic obstructive lung diseases and especially pregnancy [10,13,14].

These factors can for example contribute to a thinning or reduced tensile resistance of the linea alba, which connects the two portions of the rectus abdominis muscle. This thinning or reduced tensile resistance of the linea alba can lead to a wider inter-rectal distance (IRD) or laxity of the abdominal wall, which becomes visible as an abdominal protrusion in some cases, in others not. It is unknown, whether this wider inter-rectal distance arises from a separation of the two rectus abdominis muscles with a stretching or laxity of the linea alba or from an overexpansion of the linea alba [10,13]. The association of such changes in the structure of the abdominal wall to lower back pain and dysfunction of the pelvic floor, for example to incontinence and descensus uteri, is conflicting, as some authors promote this association, whereas others deny it [1-3,8,11,15-19]. Many women after birth consult their obstetricians, midwives and physiotherapists either with such complaints or for cosmetic reasons in cases with diastasis recti. As therapeutic interventions result from changes in the physiological structure and function, it is essential that the physiological state is assessed correctly for that group. However, there is lack of knowledge about the physiological values of the different abdominal wall muscles, especially in a homogenous, healthy, young and nulligravidous cohort. Regarding the anterior and lateral abdominal wall different studies exist, that aim to assess normative values of the inter-rectal distance, thickness of the M. rectus abdominis, M. obliquus externus and internus and M. transversus abdominis [3,4,12,20-29].

Somehow, all these different publications mostly focus on single muscles, a single or small number of measurement points along the abdominal wall, different states of muscle function, different measurement techniques and tools, dead bodies or mixed cohorts regarding sex, age and health condition. As training programs for women after birth focus on exercises of the pelvic floor and the anterior and lateral abdominal wall muscles, but no reference values are provided for that special group, the aim of this study was to provide values of the abdominal wall structures at several levels along the abdominal wall in a homogenous cohort of healthy, young, nulligravidous women at different states of muscle activation.

Material and Methods

Study Design

As part of a paramount prospective, observational study, that evaluated the influence of pregnancy on abdominal wall muscles, we examined a control group of 20 healthy, nulliparous women aged 21 to 35 years with a body mass index (BMI) less than 30 kg/m2 in our tertiary care centre between April 2015 and March 2016. The study was approved by the ethical board of the district (KEK-ZH-No. 2015-0008), followed the Declaration of Helsinki and was signed in ClinicalTrials.gov under the registration number NCT02397941. Exclusion criteria were multiple or big uterine fibroids, chronic lung disorders, collagenosis, chronic constipation, history of urine or stool incontinence, former abdominal surgery and inability to perform Valsalva manoeuvre.

Ultrasound Examination

Two well-trained ultrasound senior consultants of our obstetrical department performed all the ultrasound examinations. We measured the inter-rectal distance (IRD), the thickness of the linea alba (LA) and the greatest thickness of the M. rectus abdominis (RA) on both sides of the anterior abdominal wall at six reference points each (at the level of the umbilicus; 3, 6 and 9 centimetre (cm) above the umbilicus; 3 and 6 cm below the umbilicus) by ultrasound (Voluson E8 from GE, B-mode, 7.5 MHz 60-mm linear head transducer). The reference points were marked on the skin of every study participants with a waterproof pen, so that the correct position of the transducer could be controlled at any time. The transducer was placed perpendicular to the skin surface. Then, we measured the thickness of the lateral abdominal wall muscles (M. obliquus externus abdominis (EO), M. obliquus internus abdominis (IO) and M. transversus abdominis (TrA), on both sides halfway between the iliac crest and the inferior costal arch in the mid-axillary line, according to the method described by others [4,26,30,31]. Muscle thickness measurements on the ultrasound screen were performed by setting the caliper at the border between the hyper-echoic and hypo-echoic region perpendicular to the measured muscle. For this purpose, ultrasound has shown to be a reliable and valid technique for the assessment of muscle structure, function and activity [5,31- 40]. All clinical and ultrasound measurements were performed in supine position with the upper body flexed in 15° after voiding and emptying the bowels. Measurements were taken at the end of expiration at rest and during Valsalva manoeuvre, in order to reflect a situation of increased intraabdominal pressure as for example during pregnancy. The participants were instructed how to perform Valsalva manoeuvre before the beginning of the measuremeSnts. At every single location, we measured twice, saved the images and calculated the mean value out of those two measurements, according to the literature [4,26,41]. The probe was not moved between the measurements at every level and its position could be controlled via the skin markers. In cases of dislocation, e.g. because of movements of the study participant, it was relocated according to the skin markers.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were done for the characteristics of the study group. Continuous variables were summarized as mean and standard deviation (SD). Comparisons of the inter-rectal distances, width of the linea alba and muscle thicknesses were carried out by using one-way ANOVA for repeated measures. Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software package SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

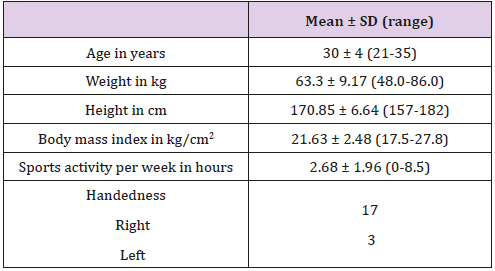

We examined 20 healthy, nulligravidous women aged 21 to 35 years with a body mass index less than 28 kg/m2. The characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

Inter-Rectal Distance (IRD) And Linea Alba (LA)

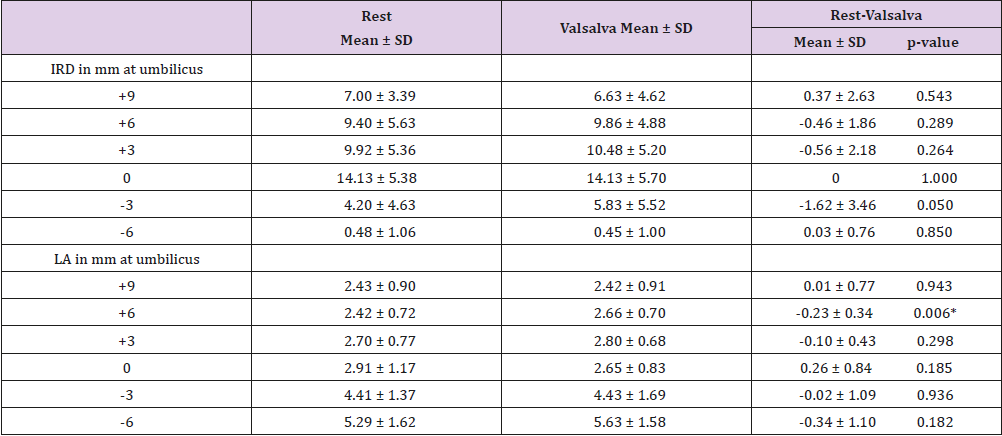

The widest IRD was found at the level of the umbilicus with a value of 14.13 mm during both Valsalva manoeuvre and at rest (Table 2). IRD in general was wider above the level of the umbilicus than below. It decreased the more distant away from the umbilicus in both directions, with values of 7.00 mm at +9 and 0.48 mm at -6 (Table 2). When comparing the values during Valsalva manoeuvre to resting state, IRD during Valsalva manoeuvre did not change at the level of the umbilicus compared to rest, but had the tendency to decrease 9 cm above and 6 cm below the umbilicus and to increase 3cm and 6cm above and 3cm below the umbilicus (Table 2). However, all changes between Valsalva and resting state were statistically not significant.

Our measurements revealed no significant differences of the thickness of the LA between rest and Valsalva manoeuvre, except at level +6 (Table 2). LA at rest was the smallest at the reference points of 9cm and 6cm above the umbilicus (2.43±0.90 mm and 2.42±0.72 mm), increased slightly towards the umbilicus (2.91 ± 1.17 mm) and further on to 5.29±1.62 mm at 6 cm below the umbilicus (Table 2).

Table 2: Inter-rectal distance (IRD) and thickness of the linea alba (LA) at rest, during Valsalva manoeuvre and its resulting changes.

Note: * Significant difference, p< 0.05.

M. Rectus Abdominis (Ra)

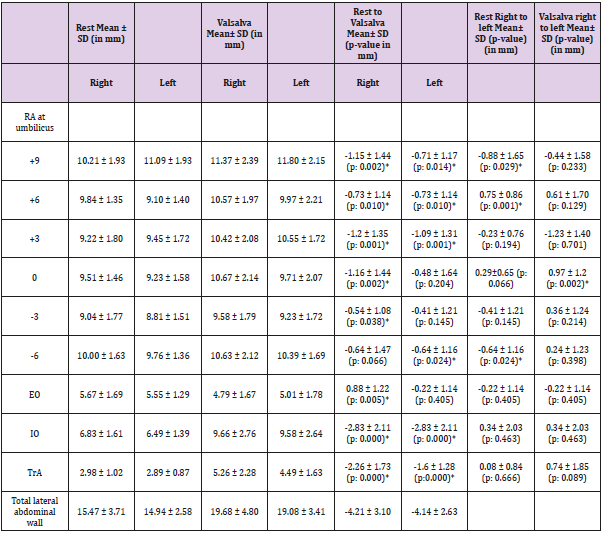

At rest, the thickness of the RA was smaller in the middle of the abdominal wall (9.23 - 9.51 mm) than near its insertion at the symphysis (9.76-10.00 mm) and rib cage (10.21 - 11.09 mm) (Table 3). During Valsalva manoeuvre, the results were more inconsistent. The greatest thickness of the RA at rest according to the side of the body (right versus left) differed depending on the abdominal level but was in average thicker on the right side of the body, but mostly statistically not significant (Table 3). The same effect was seen on the same levels during Valsalva manoeuvre (Table 3). Comparing resting state and Valsalva manoeuvre, the thickness of the RA increased at all levels during Valsalva on both abdominal, except with the RA on the right side at level -6, in most cases statistically significant (Table 3).

Lateral Abdominal Wall Muscles (TrA, IO, EO)

Regarding the lateral abdominal wall muscles, the thickness of the two inner muscles IO and TrA significantly increased during Valsalva on both sides of the body, whereas it significantly decreased in the outer muscle EO (Table 3). No significant difference was seen between the thickness of every muscle between the right and the left side during Valsalva or at rest (Table 3).

Table 3: Thickness of the RA, EO, IO, TrA and the total abdominal wall muscle thickness (IO + EO + TrA) at rest, during Valsalva manoeuvre and its resulting changes.

Note: * Significant difference, p< 0.05

Discussion

In the presented study, we evaluated values for the linea alba and the anterior and lateral abdominal wall muscles in a homogenous, healthy, young, nulligravidous cohort. Indeed, various previous studies already assessed the dimensions of the abdominal wall, but all these different publications mostly focused on single muscles, a single or small number of measurement points along the abdominal wall, different states of muscle function, different measurement techniques and tools, cadaver or mixed cohorts regarding sex, age, BMI and health condition.

Inter-Rectal Distance and Linea Alba

Inter-Rectal Distance: We found the widest IRD (14.13 mm) at the level of the umbilicus during both Valsalva manoeuvre and at rest, which is in accordance to other studies [22-24,42]. However, the values between the few other studies and ours slightly differ. Beer et al evaluated 150 nulliparous women between 20 and 45 years of age with a BMI less than 30 kg/m2 by ultrasound at only three reference points along the abdominal wall (xiphoid, 3cm above and 2 cm below the umbilicus) and only at rest [20]. The mean width of the IRD was 7 ± 5 mm at the xiphoid, 13 ± 7 mm above and 8 ± 6 mm below the umbilicus. These values differ from ours, as we found a smaller IRD above and below the umbilicus. We found 9.92 ± 5.36 mm at +3 and 4.2 ± 4.63 mm at -3. One reason for that might be the fact, that we had different measurement points along the abdominal wall than Beer et al. A second reason might be the fact, that the women in our cohort were younger and had never been pregnant or even given birth before.

The other values assessed in that study are not comparable, as we took many more reference points at different locations. Coldron et al studied 69 nulliparous women aged 18 to 45 years and found an IRD of 11.17 ± 3.62 mm at the umbilicus, which was less than in our study group with 14.13 mm [12]. Liaw et al measured an IRD of 8.5 ± 2.6 mm 2.5 cm above the umbilicus, 9.9 ± 3.1 mm at the upper margin of the umbilicus, 6.5 ± 2.3 mm at the lower margin of the umbilicus and 4.3 ± 1.7 mm 2.5 cm below the umbilicus in 20 nulliparous women aged 25 to 37 years [21]. Overall, these values were also smaller than ours were. Pascoal et al found an IRD of 9.6 ± 2.8 mm at 2 cm above the umbilicus at rest in 10 nulliparous women [43], which was also a little bit less than in our study. Whittaker et al found an IRD of 7.4 ± 3.2 mm just below the umbilicus [3]. In summary, comparing all these different studies with measurements of the IRD by ultrasound, the values differ slightly between all these studies including ours. Results of other studies regarding the assessment of IRD are unfortunately not comparable to our results, as the anthropometric data of the study cohorts were differing (postpartum women, male subjects, cadaver, older age, etc.), measurement techniques were different (calliper, digital palpation, radiologic scans) or the measurement sites differed (during surgery subcutaneously, different reference points, etc.) [22, 23,42-45]. IRD in general was wider above the level of the umbilicus than below and decreased the more distant away from the umbilicus in both directions, which is also according to other studies (20, 22, 24). We found only non-significant changes in IRD during Valsalva manoeuvre compared to resting state. No other studies are available regarding the changes of IRD during contraction states and no other studies assessed values for so many different reference points.

Thickness of the Linea Alba: LA was the largest at level -6 and decreased from level to level upward along the abdominal wall. Our measurements revealed no significant differences of the thickness of the LA between rest and Valsalva, except at level +6. To our knowledge, up to now there is no other study that investigated the thickness of LA, particularly not during Valsalva manoeuvre. An explanation for the tendency of a greater LA thickness during Valsalva might be as follows. As one performs Valsalva manoeuvre, the abdominal wall muscles are activated in such a way that the two rectus abdominis muscles contract and get thicker. By that, the anterior and posterior sheets of the rectus abdominis muscles depart and the LA consecutively gets thicker as well.

M. rectus abdominis

At rest, the thickness of the RA was in average smaller in the middle of the abdominal wall than near its insertion at the symphysis and rib cage. The same effect could be seen on the same levels during Valsalva manoeuvre (Table 3). Comparing resting state and Valsalva manoeuvre, the thickness of the RA significantly increased at almost all levels during Valsalva on both abdominal sides. No other studies exist which provide such comprehensive data of the RA in a homogenous group and at so many different abdominal levels, either at rest or during Valsalva manoeuvre. Existing studies regarding the thickness of the RA found values between 7.0 ± 2.2 mm and 11.6 ± 1.9 mm, but just measured at the level of the umbilicus and two to three cm above and below the umbilicus [3,4,12,25,26,30,46,47]. No other reference levels were evaluated there. Furthermore, study cohorts were not all-over comparable, as in the other studies mixed cohorts regarding age, sex and physical state and different evaluation methods were examined.

Lateral Abdominal Wall Muscles: The pattern of muscle thickness of the abdominal wall muscles has been reported as RA > IO > EO > TrA (4, 5, 26, 47). Our study completely agrees with these findings. Other studies reported values of 2.5 ± 0.5 to 4.7 ± 0.9 mm for TrA, 5.5 ± 1.7 mm to 11.1 ± 2.5mm for IO and 3.3 ± 0.9 mm to 10.4 ± 2.0 mm for EO at rest [3-5,26,29,30,37,46-48]. Our values for the IO and EO were within these ranges, but our values for the TrA thickness were smaller. The differences can partly be explained by the different measurement sites, as some of the studies measured the muscle sizes directly above the iliac crest and not halfway between the iliac crest and the rib cage, and by different measurement conditions, as during inspiration compared to expiration. During Valsalva we measured an increase in the thickness of the two inner muscles IO and TrA, whereas the EO decreased. Other studies agree with our findings, but the results cannot be all-over compared to ours, as the contraction manner in these studies differed from ours (leg-lift, abdominal drawing-in manoeuvre and abdominal hollowing versus Valsalva manoeuvre) [5,29,47].

Associated Factors: Body Side, Sex, Age, Body Mass Index (BMI)

In our study, there were no significant differences between the thicknesses of the lateral abdominal wall muscles at rest and during Valsalva between the two sides of the body. Rankin et al. found a significant difference for IO between left and right at rest, but not for the other muscles [4]. We found a greater muscle thickness for all of the three muscles on the right side of the body, whereas Rankin had higher values on the right side only for the IO, but greater values on the left side for the EO and TrA [4]. The problem of comparing the studies is that in the study of Rankin male and female participants were mixed together and the age range of his participants ranged from 21 to 72 years, which substantially differs from our study group. Mannion et al found no side differences for the lateral abdominal wall muscle thickness at rest in 20 males and 37 females aged 22 to 62 years [5]. But he pointed out the positive correlation between BMI and muscle thickness, the influence of gender and stated interindividual muscle asymmetry.

In the study of Tahan, significant side differences for the lateral abdominal muscles were found and gender, age and body mass index were identified as significant factors of influence on muscle thickness in his mixed cohort of 75 males and 81 females aged 18 to 44 years [26]. Men had in general thicker muscles; age was negatively associated with muscle thickness and BMI positively. However, his cohort was not comparable to ours and the reference points not the same. Ota et al also found significant difference for all of the lateral abdominal wall muscles according to age, with decreasing muscle thickness with increasing age [46]. In the study of Springer et al, no significant influence of hand dominance, but a significant influence of the BMI and sex could be shown in 15 females and 17 males aged 18 to 45 years for the TrA at rest [29]. Gill et al. (2012) evaluated 30 single-side rowers and found no significant side-to-side differences in the lateral abdominal muscle thickness, although being athletes with asymmetrical demands [48]. The study of Chiarello in postpartum women, split in an exercise and a non-exercise group, showed that postpartum exercise decreases IRD, so the amount of physical activity also changes the dimensions of the abdominal wall [24].

Strengths and Limitations

A limitation of the study is the relatively small sample size, but this is also in agreement with some of the other studies. A strength and limitation of our study at the same time is that in contrast to most of the other studies, our cohort consists of a homogeneous, healthy, young and nulligravidous cohort with a multitude of reference points along the abdominal wall. The homogeneity has the advantage that it can serve as a good control cohort for other cohorts with similar baseline characteristics than ours, for example for women after birth. In contrast, it is less good for cohorts with heterogeneous individuals regarding sex, age, parity, and others. There are different publications, which present measurements of abdominal muscle thicknesses and the inter-rectal distance, but none about values of the linea alba. Besides, our study combines capacious measurements of the inter-rectal distance, the linea alba and the thicknesses of the anterior and lateral abdominal wall muscles in one study cohort, which differs from other studies.

Furthermore, our study presents values during Valsalva manoeuvre, whereas other studies use drawing-in manoeuvre, hollowing manoeuvre or leg-lift as a form of contraction state. In general, it is questionable without doubt, if the measurement values and its changes in all the available studies including ours are in a way biased by a measurement error due to the (in)accuracy of ultrasound application for this purpose. The measured differences in ultrasound values are quite small. Moreover, we had to recognize that it might be quite difficult to capture the images strictly at the same position on the skin surface during the natural movements of the study participant at every time, although the positions were marked on the skin and the setup of the probe was always corrected. A little difference in the position of the probe along the abdominal wall will generate differing measurement values. However, we assume a similar bias towards the same direction within one examiner for all his measurements and this bias in all the published studies.

Conclusion

the level of the umbilicus, is in general wider above the level of the umbilicus than below and decreases the more distant away from the umbilicus in both directions. The thickness of the linea alba decreases from the rib cage to the symphysis. The thickness of the RA is smaller in the middle of the abdominal wall than near its insertion at the symphysis and rib cage and is in average greater on the right side of the body. According to the lateral abdominal wall muscles, the muscle thickness decreases from IO to EO to TrA at rest and is greater at the right side of the body. The effect of rest and Valsalva manoeuvre on muscle thickness, inter-rectal distance and thickness of the linea alba is inconsistent and depends on the abdominal level and the abdominal side. By comparing individual values, for example of a woman after birth, with the here provided values of a healthy, young and non-pregnant cohort, changes in the morphology of the abdominal wall in an individual with similar baseline characteristics can be detected, intervention strategies can be developed, and therapeutic procedures controlled.

References

- Hodges PW (1999) Is there a role for transversus abdominis in lumbo-pelvic stability? Manual therapy 4(2): 74-86.

- Benjamin DR, van de Water AT, Peiris CL (2014) Effects of exercise on diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle in the antenatal and postnatal periods: a systematic review. Physiotherapy 100(1): 1-8.

- Whittaker JL, Warner MB, Stokes M (2013) Comparison of the sonographic features of the abdominal wall muscles and connective tissues in individuals with and without lumbopelvic pain. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 43(1): 11-19.

- Rankin G, Stokes M, Newham DJ (2006) Abdominal muscle size and symmetry in normal subjects. Muscle Nerve 34(3): 320-326.

- Mannion AF, Pulkovski N, Toma V, Sprott H (2008) Abdominal muscle size and symmetry at rest and during abdominal hollowing exercises in healthy control subjects. J Anat 213(2): 173-182.

- Ishida H, Suehiro T, Kurozumi C, Ono K, Watanabe S (2015) Correlation Between Abdominal Muscle Thickness and Maximal Expiratory Pressure. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine 34(11): 2001-2005.

- Ehsani F, Arab AM, Jaberzadeh S, Salavati M (2016) Ultrasound measurement of deep and superficial abdominal muscles thickness during standing postural tasks in participants with and without chronic low back pain. Manual therapy 23: 98-105.

- Richardson CA, Hides JA, Wilson S, Stanton W, Snijders CJ (2004) Lumbo-pelvic joint protection against antigravity forces: motor control and segmental stiffness assessed with magnetic resonance imaging. J Gravit Physiol 11(2): P119-122.

- Richardson CA, Snijders CJ, Hides JA, Damen L, Pas MS (2002) The relation between the transversus abdominis muscles, sacroiliac joint mechanics and low back pain. Spine 27(4): 399-405.

- Akram J, Matzen SH (2014) Rectus abdominis diastasis. Journal of plastic surgery and hand surgery 48(3): 163-169.

- Gitta S, Magyar Z, Tardi P, Fuge I, Jaromi M, et al. (2017) Prevalence, potential risk factors and sequelae of diastasis recti abdominis. Orv Hetil 158(12): 454-460.

- Coldron Y, Stokes MJ, Newham DJ, Cook K (2008) Postpartum characteristics of rectus abdominis on ultrasound imaging. Manual therapy 13(2): 112-121.

- Kimmich N, Haslinger C, Kreft M, Zimmermann R (2015) Diastasis Recti Abdominis and Pregnancy. Praxis (Bern 1994) 104(15): 803-806.

- Gilleard WL, Brown JM (1996) Structure and function of the abdominal muscles in primigravid subjects during pregnancy and the immediate postbirth period. Physical therapy 76(7): 750-762.

- Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Refshauge K, Herbert RD, et al. (2010) Changes in recruitment of transversus abdominis correlate with disability in people with chronic low back pain. Br J Sports Med 44(16): 1166-1172.

- Unsgaard-Tondel M, Lund Nilsen TI, Magnussen J, Vasseljen O (2012) Is activation of transversus abdominis and obliquus internus abdominis associated with long-term changes in chronic low back pain? A prospective study with 1-year follow-up. Br J Sports Med 46(10): 729-734.

- Turan V, Colluoglu C, Turkyilmaz E, Korucuoglu U (2011) Prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in the population of young multiparous adults in Turkey. Ginekologia polska 82(11): 817-821.

- Lo T (1999) Diastasis of the Recti abdominis in pregnancy: risk factors and treatment. Physiotherapy Canada 51(1): 32-38.

- Spitznagle TM, Leong FC, Van Dillen LR (2007) Prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in a urogynecological patient population. International urogynecology journal and pelvic floor dysfunction 18(3): 321-328.

- Beer GM, Schuster A, Seifert B, Manestar M, Mihic-Probst D, et al. (2009) The normal width of the linea alba in nulliparous women. Clinical anatomy 22(6): 706-711.

- Liaw LJ, Hsu MJ, Liao CF, Liu MF, Hsu AT (2011) The relationships between interact distance measured by ultrasound imaging and abdominal muscle function in postpartum women: a 6-month follow-up study. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 41(6): 435-443.

- Rath AM, Attali P, Dumas JL, Goldlust D, Zhang J, et al. (1996) The abdominal linea alba: an anatomo-radiologic and biomechanical study. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA 18(4): 281-288.

- Boissonnault JS, Blaschak MJ (1988) Incidence of diastasis recti abdominis during the childbearing year. Physical therapy 68(7): 1082-1086.

- Chiarello CM, McAuley JA (2013) Concurrent validity of calipers and ultrasound imaging to measure interrecti distance. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 43(7): 495-503.

- Kim J, Lim H, Lee SI, Kim YJ (2012) Thickness of rectus abdominis muscle and abdominal subcutaneous fat tissue in adult women: correlation with age, pregnancy, laparotomy, and body mass index. Arch Plast Surg 39(5): 528-533.

- Tahan N, Khademi-Kalantari K, Mohseni-Bandpei MA, Mikaili S, Baghban AA, et al. (2016) Measurement of superficial and deep abdominal muscle thickness: an ultrasonography study. J Physiol Anthropol 35(1): 17.

- Stetts DM, Freund JE, Allison SC, Carpenter G (2009) A rehabilitative ultrasound imaging investigation of lateral abdominal muscle thickness in healthy aging adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther 32(2): 60-66.

- Linek P, Saulicz E, Wolny T, Mysliwiec A, Kokosz M (2014) Lateral abdominal muscle size at rest and during abdominal drawing-in manoeuvre in healthy adolescents. Manual therapy 20(1):117-123.

- Springer BA, Mielcarek BJ, Nesfield TK, Teyhen DS (2006) Relationships among lateral abdominal muscles, gender, body mass index, and hand dominance. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 36(5): 289-297.

- Weis CA, Triano JJ, Barrett J, Campbell MD, Croy M, et al. (2015) Ultrasound Assessment of Abdominal Muscle Thickness in Postpartum vs Nulliparous Women. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 38(5): 352-357.

- Ehsani F, Arab AM, Jaberzadeh S, Salavati M (2016) Ultrasound measurement of deep and superficial abdominal muscles thickness during standing postural tasks in participants with and without chronic low back pain. Manual therapy 23: 98-105.

- Tahan N, Rasouli O, Arab AM, Khademi K, Samani EN (2014) Reliability of the ultrasound measurements of abdominal muscles activity when activated with and without pelvic floor muscles contraction. Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation 27(3): 339-347.

- Teyhen D, Koppenhaver S (2011) Rehabilitative ultrasound imaging. J Physiother 57(3): 196.

- Koppenhaver SL, Hebert JJ, Parent EC, Fritz JM (2009) Rehabilitative ultrasound imaging is a valid measure of trunk muscle size and activation during most isometric sub-maximal contractions: a systematic review. The Australian journal of physiotherapy 55(3): 153-169.

- Costa LO, Maher CG, Latimer J, Hodges PW, Shirley D (2009) An investigation of the reproducibility of ultrasound measures of abdominal muscle activation in patients with chronic non-specific low back pain. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society 18(7): 1059-1065.

- McMeeken JM, Beith ID, Newham DJ, Milligan P, Critchley DJ (2004) The relationship between EMG and change in thickness of transversus abdominis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 19(4): 337-342.

- Hides JA, Miokovic T, Belavy DL, Stanton WR, Richardson CA (2007) Ultrasound imaging assessment of abdominal muscle function during drawing-in of the abdominal wall: an intrarater reliability study. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 37(8): 480-486.

- Mendes Dde A, Nahas FX, Veiga DF, Mendes FV, Figueiras RG, et al. (2007) Ultrasonography for measuring rectus abdominis muscles diastasis. Acta cirurgica brasileira / Sociedade Brasileira para Desenvolvimento Pesquisa em Cirurgia 22(3): 182-186.

- Mota P, Pascoal AG, Sancho F, Bo K (2012) Test-retest and intrarater reliability of 2dimensional ultrasound measurements of distance between rectus abdominis in women. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 42(11): 940-946.

- van de Water AT, Benjamin DR (2016) Measurement methods to assess diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle (DRAM): A systematic review of their measurement properties and meta-analytic reliability generalisation. Manual therapy 21: 41-53.

- Gnat R, Saulicz E, Miadowicz B (2012) Reliability of real-time ultrasound measurement of transversus abdominis thickness in healthy trained subjects. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society 21(8): 1508-1515.

- Brauman D (2008) Diastasis recti: clinical anatomy. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 122(5): 1564-9.

- Pascoal AG, Dionisio S, Cordeiro F, Mota P (2014) Inter-rectus distance in postpartum women can be reduced by isometric contraction of the abdominal muscles: a preliminary case-control study. Physiotherapy 100(4): 344-348.

- Barbosa S, de Sa RA, Coca Velarde LG (2013) Diastasis of rectus abdominis in the immediate puerperium: correlation between imaging diagnosis and clinical examination. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics 288(2): 299-303.

- Bursch SG (1987) Interrater reliability of diastasis recti abdominis measurement. Physical therapy. 67(7): 1077-1079.

- Ota M, Ikezoe T, Kaneoka K, Ichihashi N (2012) Age-related changes in the thickness of the deep and superficial abdominal muscles in women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 55(2): 26-30.

- Teyhen DS, Childs JD, Stokes MJ, Wright AC, Dugan JL, et al. (2012) Abdominal and lumbar multifidus muscle size and symmetry at rest and during contracted States. Normative reference ranges. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine 31(7): 1099-1110.

- Gill NW, Mason BE, Gerber JP (2012) Lateral abdominal muscle symmetry in collegiate single-sided rowers. International journal of sports physical therapy 7(1): 13-19.

Research Article

Research Article