Abstract

Purpose: Triplane fractures are a transitional fracture pattern present in adolescents with closing growth plates of the distal tibia that are difficult for orthopedic residents to conceptualize. Three-dimensional (3D) printing has been shown to increase understanding of complex anatomy and improve orthopaedic surgical planning. We hypothesize that the adjunctive use of 3D-printed models improves resident confidence and performance in treating pediatric triplane fractures.

Methods: Orthopaedic residents were randomized to study and control groups. Each participant completed a self-assessment designed to evaluate knowledge of transitional ankle fractures. Evaluation of self-confidence in treating these injuries was done using a 5-point Likert scale. Following initial testing, residents attended lectures, received a textbook excerpt, and reviewed representative computed tomography (CT) images. The study group additionally received 3D-printed models of triplane fractures. All participants re-took the self-assessment and reduced and fixed a triplane fracture model. Completed models were graded by three blinded pediatric orthopedists. Paired t-tests were used to determine between-groups differences.

Results: Sixteen residents participated. Residents in both groups demonstrated significant improvement in testing scores following the educational session (p<0.01). There was no significant difference in testing scores between groups for either clinical knowledge or applied skills. Residents in the study group showed a statistically significant increase in surgical confidence compared to the control group (p<0.05).

Conclusion: The use of 3D-printed models of pediatric triplane ankle fractures as part of a teaching module for orthopaedic residents resulted in significant improvement in self-reported confidence managing these complex injuries.

Level of Evidence: Therapeutic Level III.

Keywords: Triplane Fracture; Transitional Fracture; 3D Modeling; 3D Printing; Resident Education

Introduction

With the advent of three-dimensional (3D) printers and the advancement of medical imaging software, 3D printing is being incorporated into the medical field in myriad ways. In the fields of orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery and maxillofacial surgery, common clinical applications for 3D printing include surgical planning and customized implant design [1-4]. In the realm of medical education, 3D-printed models have been used effectively to teach complex anatomy, including that of the kidneys and perirenal system [5,6].

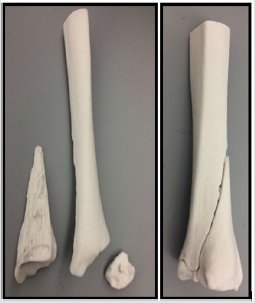

It has been demonstrated previously that 3D modelling improves a surgeon’s understanding of the spatial orientation of complex fracture patterns, including those of the humerus and acetabulum [1,2,6,7]. Adolescent triplane fractures – transitional fractures of the distal tibial physis – may be challenging to conceptualize using two-dimensional (2D) imaging modalities such as radiographs and CT (Figure 1) [8-10]. Achieving a clear understanding of fracture anatomy is crucial for planning and implementing surgical treatment. Educational modalities that enhance trainees’ understanding of this complex fracture anatomy may ultimately have an impact on clinical outcomes [11,12]. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the ability of 3D printing to meaningfully augment orthopaedic residency education. We hypothesized that the use of 3D-printed models of triplane fractures as part of a comprehensive educational program would result in improved confidence and performance.

Figure 1: Includes (A) axial, (B) coronal, and (C) sagittal CT images obtained following attempted reduction of a triplane fracture in a 13-year old female. 1B demonstrates that more than of articular diastasis remains. Reproduced from Cordelia W. Carter and A. Reed Estes. “Pediatric Knee, Leg, Ankle and Foot Trauma.” In Orthopedic Knowledge Update 12, edited by Jonathan Grauer; AAOS, Rosemont, IL 2017.

Methods

Study Design

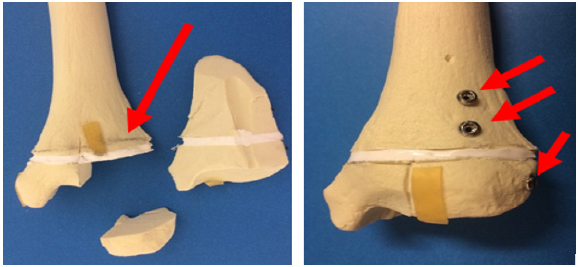

With approval from the institutional review board, orthopaedic residents were invited to participate in this prospective, controlled study. Once enrolled, residents were blindly randomized to the control group (no 3D models) or the study group (3D models). Baseline measures of each participant’s understanding of and confidence in treating triplane fractures were obtained: trainees took a novel 11-question test designed to evaluate knowledge of transitional ankle fractures. Evaluation of resident self-confidence in treating these injuries was accomplished using a 5-point Likert scale. Participants attended a multidisciplinary didactic lecture and received a textbook excerpt reviewing the management of triplane fractures. Residents were then physically divided into separate rooms by group. In both rooms, 2D CT images were available for residents to review. The study group was additionally given the opportunity to manually manipulate 3D-printed models of triplane fractures (Figure 2). Finally, after re-taking the knowledge and self-confidence assessments, residents were assigned to individual surgical skills stations and asked to perform reduction and fixation of a novel “skeletally immature” triplane fracture Sawbones model (Sawbones, Washington). To create this model, standard tibial Sawbones were cut transversely with a microsagittal saw in the expected area of the distal tibial growth plate, and a thin layer of silicone was used to reunite the resulting segments.

Figure 2: 3D printed model of a characteristic three-part triplane fracture, (A) Disassembled, and (B) Assembled. To print 3D fracture models, CT images of triplane ankle fractures were exported from Synapse (Fujifilm, Japan) into Mimics Medical software (Mimics, Belgium).12 Fracture fragments were converted into a 3D mesh and exported to 3-Matic (Materialise, Belgium). The digital models were then transferred to Z-Print software and printed in a 1:1 ratio using a ZCorp 450 plaster powder printer (3DSystems, Rock Hill, South Carolina). Models were then coated with Permabond Adhesive 101 (Ellsworth Adhesives, Wisconsin).

The final construct consisted of a proximal tibial “metaphysis” and a distal tibial “epiphysis” joined by a layer of silicone (representing the growth plate). Triplane fractures were then produced by cutting each “skeletally immature” model into three reproducible primary fragments (Figure 3). Completed fixation of Sawbones fracture models was graded as “acceptable” or “unacceptable” by a panel of three pediatric orthopaedic surgeons blinded to participant identity and training level. Restoration of joint congruity, stability of the fixation construct, and avoidance of physeal injury were the criteria used in assessment. Constructs that were mal reduced, biomechanically unsound, or created the potential for growth arrest were deemed “unacceptable”. Paired t-tests were used to determine differences between groups for performance on the written assessment, the Sawbones practical assessment and Likert responses.

Figure 3: Sawbones model of a triplane fracture, (A) Pre- and (B) Post-fixation. In Figure A the red arrow points to the silicone “physis.” The small epiphyseal fragment is seen to be separated from the physis, and the metaphysis is visible above the physis. In Figure B, the fracture has been reduced and fixed. The red arrows indicate three screws that are placed parallel to the physis and perpendicular to the fracture lines. The articular surface has been anatomically restored.

Results

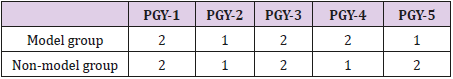

Sixteen of 25 orthopaedic residents participated in the study (64%). Table 1 shows the distribution of residents into model (study) and non-model (control) groups.

Table 1: Randomized division of 16 orthopedic surgery residents into model and non-model study groups as a function of training year.

Knowledge Assessment

The mean pre-intervention written test scores were similar for both groups (3D-model = 62.3%±15.4%; non-model = 66.5%± 16.4%). Residents in both groups had significantly higher postintervention scores (3D-model = 82.1%±8.6%; non-model = 80.1%±13.9%), (p<0.01). There was no significant difference in improvement between groups (p>0.05).

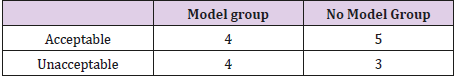

Skills Assessment

Each completed Sawbones was graded in a binary fashion according to the criteria described above (Table 2). The “acceptable” rate was 50% in the model group and 63% in the non-model group. There was no significant difference between the groups for quality of Sawbones fixation (p>0.05).

Table 2: Grades for quality of Sawbones fracture reduction and fixation. For a Sawbones to be “acceptable,” joint congruity had to be restored and fixation had to be both biomechanically sound and physis-sparing.

Self-Confidence Assessment

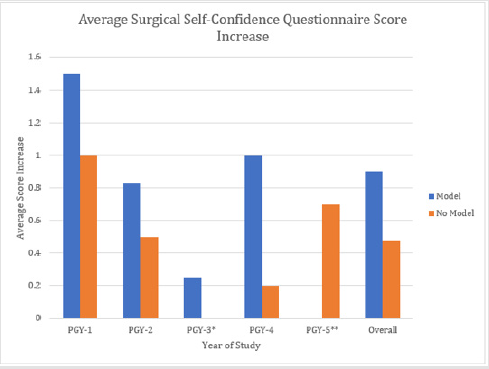

There was a statistically significant difference in the increase in self-reported confidence for residents in the model group compared to the non-model group (p=0.02; Figure 4).

Figure 4: Likert score change from pre-education session and post-education session for the groups that received a 3D model and those that did not. The overall Likert score self-confidence increase had a statistically significant difference for the model group vs the nonmodel group (p=0.02). *The PGY-3 “no model” group had an average score increase of 0. **No PGY-5 residents in the “model” group completed the post-intervention confidence assessment.

Discussion

In the field of medicine, 3D printing is used increasingly for surgical planning, implant design, and to enhance understanding of complex anatomy. Additionally, 3D printing has great potential utility in the realm of medical education. Several studies have previously explored the use of physical 3D models as medical teaching aids. Challoner and Erolin compared the use of virtual 3D models to physical 3D models for teaching anatomy of the renal system and found that physical models were favored; participants additionally reported that the “tactile input” and ability to interact with the models strengthened their understanding of the intricate anatomical relationships [3]. Multiple studies have examined the use of physical 3D models as teaching aids for surgical trainees: 3D models have been shown to improve trainees’ abilities to understand acetabular fractures, [2,6] plan upper extremity osteotomies, [1] learn the trans-sylvian approach to the brain,4 prepare for surgical clipping of aneurysms, [13] plan repair of orbital floor fractures, [14] plan mandibular reconstructions,3 and prepare for percutaneous nephrolithotomies [5].

In this study, we evaluated 3D-printed models of triplane fractures as educational adjuncts for orthopaedic surgery trainees, specifically examining changes in resident knowledge, confidence, and “surgical” performance compared to traditional teaching methods. While there was no difference in the scores for knowledge and clinical skills between residents exposed to 3D models and those only exposed to traditional imaging modalities, there was a significant increase in self-confidence scores for residents who had interacted with 3D-printed models versus their “3D-naïve” peers. Specifically, residents in the study group were more confident in their ability to conceptualize a complex triplane fracture and devise a surgical treatment plan. This improved confidence may in turn, improve the quality of orthopaedic care. Additionally, trainees’ confidence gained from this type of “experiential learning” could be potentially extrapolated to other rare medical illnesses and injuries that require understanding of complex anatomy.

Possible future directions for this study are manifold: if 3D-printed models of a particular fracture are available prior to operative intervention such that surgical planning is streamlined, operative time and cost could potentially be decreased. With better understanding of a patient’s unique fracture pattern prior to surgery, there is the potential to decrease use and exposure to intraoperative fluoroscopy. Recognizing that residents have different learning styles, we could potentially identify trainees who would most benefit most from the use of 3D-printed teaching adjuncts and target them specifically. The use of 3D-printed models as a method of experiential learning might also prove valuable to educators working on ACGME milestones or those using highfidelity simulation methods. This study has certain limitations, the most significant of which is its small sample size: it is possible that this investigation was insufficiently powered to detect significant differences between groups. Additionally, the knowledge assessment post-test was given shortly after the pre-test and hence is susceptible to recency bias. Finally, we are unable to comment on the durability of our findings; we cannot say whether the improved degree of self-confidence associated with the tactile experience of a 3D-printed model would be maintained over a prolonged period.

Conclusion

3D printing has a vast array of potential uses, including the enhancement of medical education. By increasing a surgical resident’s confidence in his/her ability to manage complex triplane fracture patterns, 3D printing may have the potential to improve orthopaedic care.

References

- Schweizer A, Fürnstahl P, Nagy L (2014) [Three-dimensional planing and correction of osteotomies in the forearm and the hand]. Therapeutische Umschau. Revue therapeutique 71(7): 391-396.

- Hurson C, Tansey A, O’donnchadha B, Nicholson P, Rice J, et al. (2007) Rapid prototyping in the assessment, classification and preoperative planning of acetabular fractures. Injury 38(10): 1158-1162.

- Dziegielewski PT, Zhu J, King B, Grosvenor A, Dobrovolsky W, et al. (2011) Three-dimensional biomodeling in complex mandibular reconstruction and surgical simulation: prospective trial. Journal of otolaryngologyhead & neck surgery 40: S70-81.

- Harada N, Kondo K, Miyazaki C, Nomoto J, Kitajima S, et al. (2011) Modified three-dimensional brain model for study of the trans-sylvian approach. Neurologia medico-chirurgica 51(8): 567-571.

- Turney BW (2014) A new model with an anatomically accurate human renal collecting system for training in fluoroscopy-guided percutaneous nephrolithotomy access. Journal of Endourology 28(3): 360-363.

- Hansen E, Marmor M, Matityahu A (2012) Impact of a three-dimensional “hands-on” anatomic teaching module on acetabular fracture pattern recognition by orthopaedic residents. J Bone Joint Surg Am 94(23): e177.

- Brouwer KM, Lindenhovius AL, Dyer GS, Zurakowski D, Mudgal CS, et al. (2012) Diagnostic accuracy of 2-and 3-dimensional imaging and modeling of distal humerus fractures. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 21(6): 772-776.

- Cooperman DR, Spiegel P, Laros G (1978) Tibial fractures involving the ankle in children. The so-called triplane epiphyseal fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 60(8): 1040-1046.

- Carter CW, Estes R (2017) Pediatric Knee, Leg, Ankle and Foot Trauma. Orthopaedic Knowledge Update.

- Torres K, Staskiewicz G, Sniezynski M, Drop A, Maciejewski R (2011) Application of rapid prototyping techniques for modelling of anatomical structures in medical training and education. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 70(1): 1-4.

- Martin CM, Roach VA, Nguyen N, Rice CL, Wilson TD (2013) Comparison of 3D reconstructive technologies used for morphometric research and the translation of knowledge using a decision matrix. Anatomical sciences education 6(6): 393-403.

- Kimura T, Morita A, Nishimura K, Aiyama H, Itoh H, et al. (2009) Simulation of and Training for Cerebral Aneurysm Clipping with 3‐ Dimensional Models. Neurosurgery 65(4): 719-726.

- Kozakiewicz M, Elgalal M, Loba P, Komuński P, Arkuszewski P, et al. (2009) Clinical application of 3D pre-bent titanium implants for orbital floor fractures. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery 37(4): 229-234.

Research Article

Research Article