Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Machado ER*1,2, Moura CS1, Silva MA1, Eduardo AMLN1, Oliviera LB1, Melo KS1, Chaves PLG1 and Miranda CC1

Received: December 08, 2018; Published: December 19, 2018

*Corresponding author: Eleuza Rodrigues Machado, Nursing Course, Anhanguera Faculty of Brasília, Brazil

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.12.002245

Toxoplasmosis is caused by T. gondii, with prevalence from 20 to 90% in the world population. In pregnant women, the presence of fetal infection reaches 40%. The aim of the study was to determine the frequency and risk factors of toxoplasmosis in pregnant women receiving care at health centers in the city of Samambaia in the Federal District. Two groups of women: one group included pregnant women who attended prenatal programs in 2014 using interviews and a printed questionnaire. The other group included pregnant women randomly selected from records in the system of the health centers. These women had had serological tests for toxoplasmosis conducted in 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014. A total of 414 pregnant women participated in the study: 200 that were interviewed and 214 by way of secondary data obtained between 2011 and 2014. Of these secondary data, the prevalence of susceptible pregnant women was 39%, those immune were 34% and those infected during pregnancy, 27%. They were between 21-25 years of age, little education and poor information about prevention to toxoplasmosis. The prevalence of immune susceptible and infected pregnant women varies by age, level of education and information about toxoplasmosis in the first pregnancy.

Keywords: Toxoplasmosis; Pregnant Women; Congenital Toxoplasmosis; Samambaia; Federal District

Toxoplasmosis is a disease caused by Toxoplasma gondii with cosmopolitan distribution [1]. This disease affects various mammals: cats, pigs, rodents and cattle as well as humans [2-4]. It is a serious public health problem, possibly causing irreversible damage or even death for the fetuses of pregnant women and immunocompromised individuals [5-7]. The prevalence of toxoplasmosis varies from 20 to 90% in the world population but with different geographical distribution from one region to another. It depends on risk factors, such as food, water treatment, environmental exposure and cultural habits [8,9]. Pregnant women who have acquired toxoplasmosis transmit the disease to fetuses, causing miscarriages, stillbirths, neurological and ocular sequelae [10,11]. There are three infectious stages of T. gondii: the tachyzoites (in groups or clones), the bradyzoites (in tissue cysts), and the sporozoites (in oocysts). These are intracellular, preferably in cells of the mononuclear phagocytic system [12-14]. In the sexual stage they infect the intestines of young cats. In the asexual stage the eye tissue, muscle and brain of birds and mammals, including man, are infected [15-17]. Transmission of T. gondii is oral, with the ingestion of cat feces containing oocysts that had been present in soil, water, sand boxes or unwashed fruit and vegetables. Infection can also occur by eating raw or undercooked meat containing cysts with bradyzoites, or tachyzoites in milk, or by laboratory accidents, blood transfusions or it may be transplacental [18,19].

The pathogenesis of toxoplasmosis varies from benign to severe cases, possibly with lesions, in the central nervous system and retina [20,21]. This variability is dependent on the degree of virulence of the strain transmission route, condition and age of the patient [22]. In pregnant women, toxoplasmosis causes various symptoms, the most common: lymphadenopathy, asthenia, fever, malaise, headache, myalgia, macula papular rash, sore throat due to pharyngitis and hepatosplenomegaly. These symptoms appear in about 10 to 20% of cases [23,24]. In the fetus, the disease is severe and can cause miscarriage or stillbirth. The newborn may have severe neurological sequelae such as blindness. Such symptoms, however, cannot be observed at birth but appear over time [25,26]. The diagnosis of toxoplasmosis is made by parasitological or immunological tests. Parasitological parasites are detected in body fluids and tissues, or anti-T gondii specific antibodies, using immunological methods [27].

In cases of positive serology for toxoplasmosis during pregnancy, or acute infection, treatment should be started immediately to prevent fetal infection and reduce numbers of circulating parasites in the mothers along with the emergence of problems in pregnancy: miscarriage, premature birth and serious sequelae in the fetus. The treatment involves the use of spiramycin, sulfadiazine with pyrimethamine and folinic acid [28-30]. Diagnosis of Toxoplasmosis in pregnant women in Brazil should be made during prenatal care. Pregnant women should know about the disease and how to prevent it in the first prenatal visit. The hygienic and dietary guidelines are forms of primary prevention of this protozoan infection and can be passed to pregnant women individually or in consultations during prenatal meetings. The objective of the study was to determine the frequency and risk factors of toxoplasmosis among pregnant women receiving care at public health centers in the city of Samambaia, DF, Brazil.

Results were collected from 214 women that had information about toxoplasmosis stored in the systems of the health centers in the city of Samambaia in the Federal District of Brasília, DF. The prevalence of antibodies anti-T. gondii was investigated in these women. The serologic methods applied in the tests of the secondary data, in the diagnosis of gestational toxoplasmosis, were fluorescent immunoassay test (ELFA) and immunoenzymatic (ELISA). The 200 women who were interviewed in the research were attending or had attended prenatal programs and agreed to participate in the study by signing the Informed Consent (IC). In this group the data were collected from interviews and a questionnaire with objective questions about socio-economic aspects, prenatal conditions, hygiene and diet.

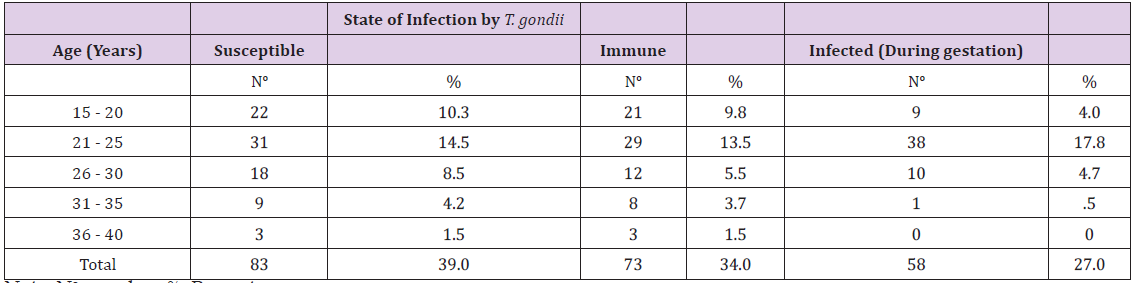

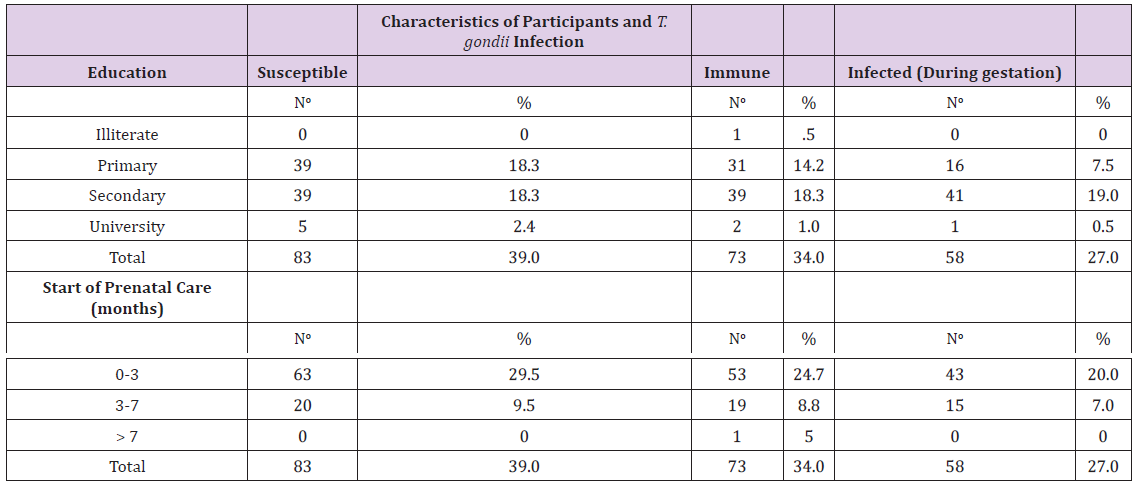

The medical records of 214 pregnant women included: 70 in 2011, 72 in 2012, 65 in 2013 and seven in 2014. These women were of different ages and different periods of pregnancy. The results obtained by ELFA and ELISA permitted classification of these women into three groups: susceptible, immune or infected by T. gondii during pregnancy. Of the 214 records studied, 83 were negative for IgM and IgG anti-T. gondii thus these women were likely to contract toxoplasmosis. Seventy-three of the women were IgG positive and had been infected by T. gondii before pregnancy. There were 58, who tested positive for IgM anti-T. gondii infection and had acquired it during pregnancy. The ages of these women are described in Table 1. Susceptible women, those who were immune and those who had acquired toxoplasmosis during pregnancy, are distributed according to levels of education and early prenatal care (time in months) in (Table 2).

Table 1: Distribution of information from medical records of pregnant women attending health centers, according to age and stages of T. gondii infection, 2011 to 2014.

Note: No: number; %: Percentage

Table 2: Distribution of information from medical records of pregnant women attending health centers regarding schooling and time of starting prenatal care, 2011 to 2014.

Note: No: number; %: Percentage.

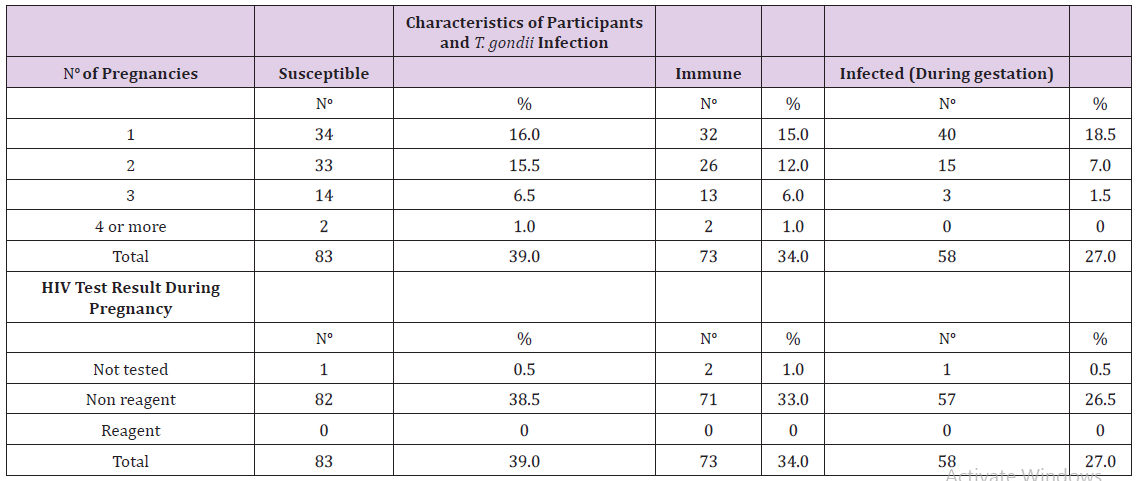

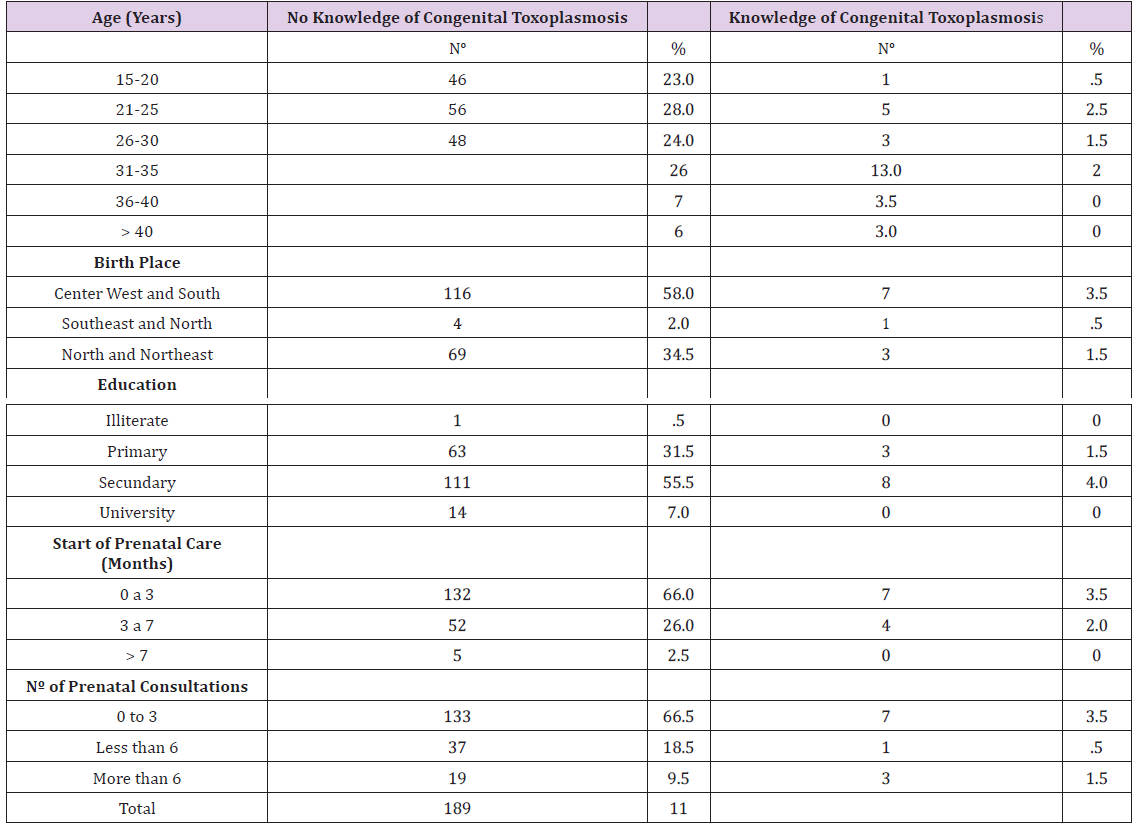

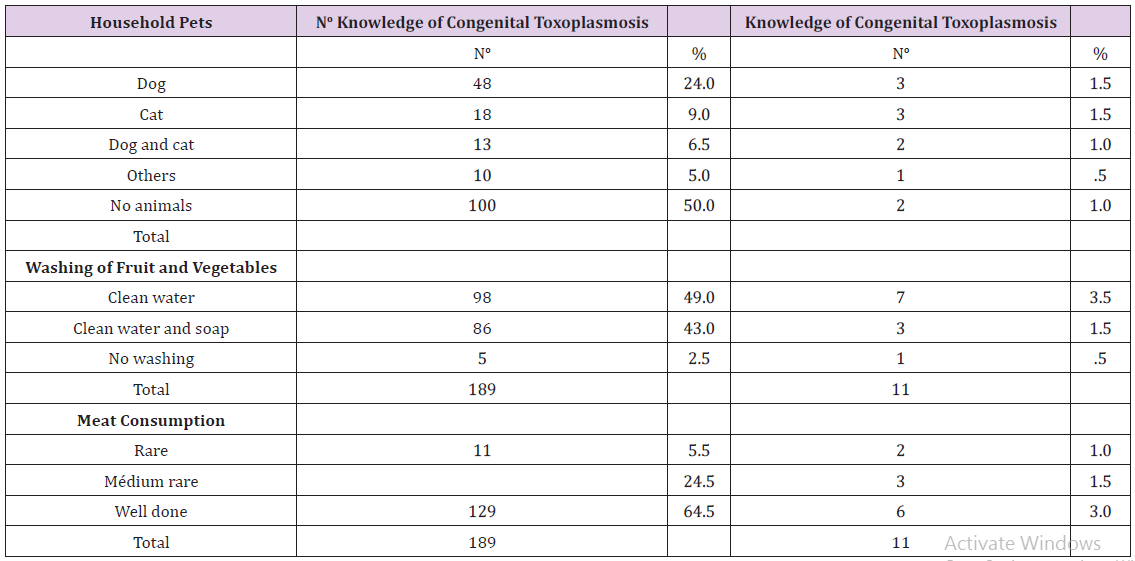

Susceptible women, those who were immune and those who had acquired toxoplasmosis during pregnancy, are distributed according to the number of pregnancies and test results for HIV, in Table 3. Results obtained from the 200 women interviewed in 2014 concerning the degree of knowledge and risk factors for acquisition of gestational toxoplasmosis are presented in Table 4. These women originated from different regions of Brazil including the Midwest, North and Northeast. They are distributed according to their levels of education. Of the 200 women, only eight had completed high school. Three had completed primary school and had knowledge of congenital toxoplasmosis. The time that these women started prenatal care is grouped and identifies the number of times they sought a professional for prenatal care (Table 4). The degree of knowledge of toxoplasmosis and predisposing factors for acquisition of the disease during pregnancy including sanitary conditions, presence of household pets, gardening or garden activities, washing habits for fruits and vegetables and consumption of meat is described in Table 5.

Table 3: Distribution of information from medical records of pregnant women attending health centers regarding numbers of pregnancies and the results of HIV tests, 2011 to 2014.

Note: No: number; %: Percentage.

Table 4: Distribution of information from pregnant women interviewed and attending health centers regarding knowledge of congenital toxoplasmosis, age, birth place, education, early prenatal care (in months), and number of prenatal consultations in 2014.

Note: No: number; %: Percentage.

Table 5: Distribution of 200 pregnant women attending health centers regarding hygiene and dietary habits, 2014.

Note: No: number; %: Percentage.

Infection by gestational toxoplasmosis was found in 83 (38.8%) of the cases of the women susceptible to infection, of the present study. These results differ from the results of a study in the State of Mato Grosso do Sul, where 91.6% of pregnant women were immune, of 32.512 pregnant women [31]. In a study conducted in Porto Alegre, RS, the majority of 1,261 pregnant women studied were immune [32]. These results suggest that the prevalence of toxoplasmosis in pregnant women varies from one geographic region to another, possibly due to differences related to culture, hygiene, and diet [33]. The most prevalent age for toxoplasmosis infection, for all pregnant women: susceptible, immune or infected, during pregnancy was between 21 and 25. In a similar study conducted in Mato Grosso do Sul, the average age was 23 for women infected during pregnancy [31]. In Rolândia, Paraná, the prevalent age was 36-45 for immune mothers [34]. All the surveys reviewed show that most human cases of primary toxoplasmosis occur in young people. In Brazil, there are several studies that demonstrate the importance of education as a protective factor for preventing toxoplasmosis.

There are also studies that discuss the importance of creating health education programs to teach the use of hygiene and dietary habits in order to prevent the disease in pregnancy [35,36]. The results found in this study did not identify education as a risk factor for congenital infection because most women infected during pregnancy had only primary or a secondary school education. In the present study, it was observed that most of the women began prenatal care in the first trimester, independent of whether they have knowledge of congenital toxoplasmosis, or had been instructed, in previous prenatal care, about the disease. In a similar survey conducted in Goiânia, 54.6% of the pregnant women surveyed were also screened in the first quarter, thus receiving more information and more prenatal care than women who began prenatal care in the last two quarters [35]. In terms of numbers of pregnancies, the numbers of susceptible and immune pregnant women were similar among those in the first or second pregnancy.

An important fact was that most pregnant women who become infected with T. gondii were in their first pregnancies and began prenatal care in the first trimester. These data show the importance of starting prenatal care early and that pregnant women receive special attention and are oriented to continuously seek consultations and laboratory tests to avoid contracting the disease or, if infected, to start treatment immediately [37]. All participants, among the secondary sample examined, had serologic tests for HIV detection. This test is important because HIV positive patients may have acute relapses or new infections of chronic toxoplasmosis. This parasite is opportunistic in HIV individuals and can trigger a serious situation that could cause death if not treated early, or make possible a vertical transmission [38,39]. Most of the women interviewed about their knowledge concerning toxoplasmosis knew very little or had not heard of the disease. Those who had information had received it from a family member.

Only 5.5% had received information about this protozoan infection during the prenatal period. In a study conducted in Belo Horizonte, 54.6% of 163 women surveyed had been instructed on the prevention of toxoplasmosis during pregnancy [40]. Another study, conducted in southern Brazil, showed that only 3.4% of pregnant women had not received any information or care about gestational toxoplasmosis [41]. Comparing the data from this survey with other studies, it was apparent that prenatal care in Samambaia, DF leaves much to be desired regarding the guidance given pregnant women. The principal concern is the large number of cases of toxoplasmosis acquired during pregnancy [42]. The results of our research show that the very young women interviewed, aged 15 to 25, were the least informed about congenital toxoplasmosis. Those that knew anything about this disease were older. Regarding the origin of these women, most were from the Midwest, where the study was conducted.

It was also observed that most of the women interviewed had primary or secondary education; however, it was not clear that education was associated with the decision to participate in prenatal care. On the contrary, many women said that they went, habitually, to the health centers and were treated hastily without questions or explanations about the major diseases in pregnancy. Education was important for women to be more aware of the necessity of hygiene to prevent diseases. Our results corroborate descriptions found in the literature alleging that education is a protective factor against toxoplasmosis during pregnancy [35,36]. One factor that may have contributed to the lack of knowledge of the pregnant women interviewed is the low number of prenatal consultations, a maximum of three times per woman. In a study conducted in São Paulo, the authors suggest that infrequent appointments make it difficult for women to be well informed about the preventive methods for toxoplasma. They also prevent the detection of new cases, making it impossible for an early treatment with spiramycin, which would prevent congenital transmission [43,44]. Another important aspect analyzed in our study concerned the access of pregnant women to basic sanitation and safe drinking water.

These were serious factors for protection against toxoplasmosis in the pregnant women questioned in Samambaia. These data corroborate a study in Paraná, which shows that unsafe drinking water is a risk factor for infection by T. gondii [34]. Most of the pregnant women of our study explained that they did not handle soil with their hands and did not customarily perform this type of activity. They reported regular washing of their hands after cutting raw meat. According to the literature, pregnant women should only work with soil using gloves and always wash the hands after cutting raw meat. These activities are important risk factors in the acquisition of toxoplasmosis [45]. With respect to having pets in the home, the majority of those interviewed reported not having animals. Cats were the most frequent pets of the women studied, even though they knew that this animal transmits disease. Researchers in Brazil have found women who had contact with cats and were infected with T. gondii during pregnancy [41]. It is thus important for professionals who work in the area of prenatal care to have knowledge about the risk factors for acquisition of T. gondii so that they will be prepared to orient women in prenatal consultations on this parasitosis.

The custom of washing fruits and vegetables by the women of the study left a lot to be desired. Most were washing raw foods just with water. More than half of the women reported eating well done or cooked meat. Some researchers have shown that the consumption of undercooked meat can contribute to T. gondii infection, although it has also been found that freezing at a temperature of -20 °C for 18 to 24 hours destroys the cysts present in contaminated meat [42]. The literature is consistent in demonstrating that the transmission of toxoplasmosis is higher in places where people have poor hygienic habits when preparing food [43,45]. Thus, the information obtained in this study of congenital toxoplasmosis and risk factors for acquiring this disease, verifies reasons for further studies in health centers, not only in the Federal District, throughout Brazil. We need not only to know the real situation of this disease in pregnant women but also to provide information for guidance programs to be developed and passed on during prenatal care. Only with adequate knowledge and effective programs will it be possible to improve the quality of life of pregnant women and of the future generation, yet to be born [46-48].

The prevalence of gestational toxoplasmosis among the pregnant women of both samples who received and prenatal care at the health care clinic of Samambaia was high. This fact was related to low levels of knowledge, among the women interviewed, about the disease due to their youth and their little education. The results of our study suggest the need for greater disclosure of toxoplasmosis and transmission. Considering that many women have low education and poor access to the means of formal information, information on toxoplasmosis for pregnant women must be the responsibility of multidisciplinary health teams. Health professionals in prenatal program need to know present and exemplify actions and services aimed at the promotion and prevention of toxoplasmosis. The humanized and systematic assistance to patients in their first as well as in subsequent pregnancies can minimize gestational toxoplasmosis and avoid the numerous consequences of this disease of the fetus.

We express our appreciation to the future mothers cared for at the Health Centers in the city of Samambaia, DF. Their participation was essential for the research.