Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Kwiatkowski Fabrice*1 and Ducher Jean-Luc2

Received: December 05, 2018; Published: December 14, 2018

*Corresponding author: Kwiatkowski Fabrice, Statistician (MSc), Statistics Unit, Centre Jean Perrin, France

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.12.002211

Context: Suicide risk evaluation has always been of importance for patients’ care, but it has recently become a major concern for clinical research. According to DSM-5 experts, new tools still need to be developed to better evaluate this risk. RSD scale (Risk for Suicide of Ducher) described hereafter, was created thirty years ago.

Methods: It consists in a hetero-questionnaire yielding a score from 0 to 10, 10 being the decisional level for the patient regarding a possible acting out. The scoring of the scale during the consultation by a psychiatrist or a physician does not need more than a few minutes. All studies that used RSD scale are included in this review.

Results: Outcomes and conclusions are synthetized to document its global metrologic properties. The scale has been tested in various situations (adolescents, adults, males and females, without/after a suicidal attempt) and in particular in a prospective trial to compare the efficacy of two antidepressants on depression and the suicidal risk in patients presenting with recurrent depressive disorder. In this latter, RSD was associated with 100% sensitivity and 87% specificity to predict suicide under treatment.

Conclusion: RSD seems to fit with recent guide-lines about suicide prevention but new studies in English-speaking countries are necessary to confirm its transcultural validity, and its interest in patients’ management as well as clinical trials.

Keywords: Suicide; Suicidal crisis; Scale; Questionnaire; RSD; Prevention; Review

Suicide is one of the main causes of death in Occident. In western countries, it concerns various categories of individuals, such as adolescents and young adults (age 15-25 years) for whom it represents the third leading cause of death in the US, and the elderly: white men over 85 exceed the national average by 6-fold [1]. According to the World Health Organization, the “global” worldwide mortality rate by suicide was estimated at 16/100 000 inhabitants in 2000 and present figures are similar. In the US, males are about 4 times more likely to commit suicide than females: 18 versus 5/100 000. This rate for men is even higher in countries with former socialist economies: Czech Republic 26/100,000, Poland 28, Croatia 30, Hungary 42, Kazakhstan 45, Russia 58, Lithuania 68. Asian males also face this burden (30 in Korea, 35 in Japan), and so do western European males (Germany 20, Sweden 20, France 26, Finland 31). Suicide rates have increased by 60% in the last 50 years. This does not include suicidal attempts which are 20 times more frequent than completed suicides and that occurs differently according to sex and age. Longly ignored, this problem now a days focuses the attention and efforts of governments and public health services. Suicide is now considered to be an indicator of the society state. In many countries, and particularly the USA, suicide prevention has become a national public health priority [2,3]. A lot of studies have attempted to puzzle out suicidary dimension. Following Aaron T. Beck, many researchers, physicians, psychiatrists and psychologists have investigated its psychosocial context and suicidal persons’ traits, quite often in relation with depression and/or schizophrenia. New approaches could be devised with the development of neurosciences. On the other hand, the management of person at risk of suicide has greatly progressed. Traditionally, psychosocial interventions were used to prevent attempts and recurrences. But unfortunately, reliable data on whether psychosocial treatments actually reduce suicidality is still limited [4].

Today, medical treatments seem to be preferred although new approaches are investigated like mindfulness [5]. The competition between pharmaceutical industries in this domain introduces new needs and pitfalls as in other medical domains (oncology for example): the efficacy of treatments needs to be evaluated on relevant data. In the last few decades, some effort has been put on the development of tools permitting a better characterization of suicide attempts and the follow-up of suicidal crisis. The need for such tools was emphasized by the FDA, seeking to favor the evaluation of therapeutical strategies based on standardized definitions (i.e. to agree on what should be labeled suicide or not) and make clinical trials in this field more comparable. The best example of such tools is the C-CASA [6] scale. It follows the classification scheme for suicidal behavior edicted in 1973 by the Center for the Study of Suicide and Prevention of the NIMH, chaired by Aaron T Beck [7]. Suicidal phenomena are described as completed suicides, suicide attempts and suicide ideation. Subgroups were put forward to enable a better classification of suicidal behaviours and thoughts.

But characterization of suicidal events does not mean prediction. Many other works have tried to determine factors that could correlate the incidence of suicide. Among them, some point at socio-economic dimensions on which medical or psychological interventions have little or no effect: weapon ownership [8], divorce and unemployment [9], old age [1], and for younger people alcohol/drug use, victimization and health problems [10]. Other studies attempt to define psychological factors associated to the suicidal risk. The main questionnaire that has shown a significant predictive value for suicide is the Hopelessness scale [11,12], although contradictory results have been reported by Beck himself in parallel with his scale for Suicidal Ideation [11,13,14]. Similar discrepancies have been reported with Beck’s Suicidal Intent Scale [15], but more recent results appear more robust despite a weak positive predictive value of this scale, estimated at 4% [16,17]. Works investigating the predictive value of depression scales remain scarce: in Beck’s study on his depression inventory scale, scores were weakly associated with further suicide (p = 0.06) [11]. Other cognitive factors also seem to predict suicide as intentions and passive thoughts about wanting to be dead [18,19].

For clinical reasons, tools permitting to evaluate correctly the suicidal risk of patients are essential: before letting the patient leaving the hospital, psychiatrists need to ensure that he will not threaten his life shortly after. Open interview may often be sufficient for the physician to determine if his patient needs to remain hospitalized or not. But a more structured interview may help decide about this question. This article introduces the RSD scale, a hetero-evaluation questionnaire based on a cognitive model of decision making, adapted to suicidal events. Several paragraphs will document this subject. First of all, the RSD scale will be shortly described: two appendixes detail the content of the scale and its passation mode. Different validation methods are then reported in order to define the metrologic properties of the scale as well as its possible use. Finally, a brief discussion sums up the strengths and weaknesses of the instrument, and further developments to expect a generalization of its use.

The suicidal risk assessment scale of Ducher (RSD) has first been reported in France by Charles in 1990 [20]. Its goal was to estimate the intensity of the suicidal risk. It evaluates a possible will to commit suicide rather than a single assessment of the frequency of suicidal thoughts. Its construction in hierarchical order permits the progressive rating of the suicidal risk, in the form of a semistructured interview. It comprises 11 ascending levels (Table 1). After a first level quoted zero, where the suicidal risk is estimated to be null, a set of 5 items evaluates ideations about death and suicide, then a set of 5 other steps concerns the will to die. From 1 to 5, we find suicide thoughts without desire to act out and from 6 to 10, suicide thoughts with a desire to die. In the lower items group, the RSD scale looks for the existence of death thoughts (Levels 1-2), of suicide ideation and its frequency (Levels 3-4-5). The second group introduces a progression in the will do die, first passive, then retained, decided, planned and acted. It starts with passive desire to die (Level 6), followed by level 7 which shows the onset of a decision-making process, except that the patient is still inhibited by various important factors in his/her life. Usually, fear of causing pain to one’s relatives or religious beliefs is evoked. From level 8, determination has made way to hesitation. An active will of death exists, and although the plan remains undefined, the act is decided upon. At level 9, the methods of application are defined, and a plan is established. The ultimate level is reached when the preparation of the act of suicide has started (Level 10).

A trained psychiatrist needs less than 2 minutes in average to evaluate the suicidal risk with the RSD scale. Up to now, the only available form was the hetero-questionnaire. But recently a modification of the scale has been made so that it can be used as self-questionnaire by patients themselves (named hereafter aRSD): patient is asked to quote all the items corresponding to his state of mind. Then a practician or an assistant can easily determine the RSD score, by retaining the highest quoted level.

Construct Validity, Internal Validity, Test-Retest, Inter- Judge Reliability

a) Construct Validity: This hierarchical order of the RSD scale has been partially confirmed by an epidemiological study [21] reported in the French Consensus Conference about suicidal crisis [22]. In this study, a distinction was made on a conceptual level between suicidal ideation and suicidal planning. The former was associated to 26% of suicidal attempts on the long term versus 72% for the latter. For the attempts occurring during the 2 years following the suicidal ideation, more than 50% of the persons with plans made a suicidal attempt versus only 22% among the persons without plan. For these 22%, most suicidal attempts were deemed impulsive. These authors show that there is a big gap between ideation and planning, and that they represent two very different suicide risk levels. The Montgomery’s MADRS scale [23], although it focuses on depression, shows a quantitative distinction among suicidal ideations with its 10th item (suicidal ideas). It splits suicidal ideations according to their frequency and the level of intention. Its last level also concerns planning. The particularity of the RSD scale is to bring new steps:

i. At the beginning, a distinction is made between ideas of death and ideas of suicide, which are considered more meaningful.

ii. Over the ideation items, a new step (the 6th one) concerns a passive desire to die: by accident, disease, but not with selfinjury. This passive attitude is evaluated in Beck’s Scale for Suicidal Ideation [14], but in a different way.

iii. At level 7, some reasons still prevent the subject from acting out: religious beliefs, fear of causing pain.

iv. These arguments become insufficient at the upper levels where an active will is at work and the decision is made. Level 8 states that no plan is established conversely to the 9th level. The preparation of the suicide or the beginning of the acting characterizes the last level.

b) Internal Validity/Consistency: This topic enables to evaluate the coherence between the various items of a scale. Since the RSD scale is a graduated evaluation that retains a unique value - the highest one - this validation was impossible.

c) Test-retest: This validation has not been tested since the score is supposed to permit the follow-up of the suicidal crisis. In such a case, intervention of the psychiatrist is required and thus induces variations over short periods of time. Therefore, a testretest analysis did not appear relevant.

d) Inter-Judge Reliability

An aspect of such reliability has been explored by comparing the scores obtained with the self-questionnaires aRSD completed by the patients and the evaluations by the psychiatrists themselves of RSD score. Preliminary results are available on 50 patients. Correlation coefficient between patients’ and practicians’ scores was 0.95 (p< 10-7) and a paired Student t-test showed no difference between patients’ and psychiatrists’ evaluations (p=0.14), although patients tended to lower very slightly their scoring (4.33.1 versus 4.62.9). The Bland and Altman test were not significant either (p=0.93) indicating the correlation did not depend on the level of suicidal risk.

a) Concurrent Validity

The correlations with other scales are a good indicator to assess the validity of a scale although too strong correlations can also indicate that the scale may be redundant. Several studies [20,24-30] have questioned this issue. (Table 2) sums up the main relationships found between the RSD scale and various questionnaires. Interestingly, these studies have focused on different populations, such as patients hospitalized in a psychiatric emergency unit [31], outpatients in psychiatry or young individuals consulting a preventive health centre [27]. Also, various types of psychological profiles were encountered: major depressive episode, severe and/or recurrent depressive disorder, suicidal attempts... We detail hereafter the listed works.

Charles [20] has been the first to study the metrological qualities of the RSD scale. He has included 100 adults presenting with mood disorder while consulting at the French Neurological Hospital of Lyon. This survey has been published in 1992 and 1994 by Bouvard et al. [24,25] with complementary results regarding the French validation of Beck’s hopelessness scale [32], the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire [33] and Weissman’s Dysfunctional Attitudes scale form A [34]. Results showed strong correlations between the RSD scale and:

a. The hopelessness scales r=0.64 (p< 0.001)

b. The level of depression rated by the clinician evaluating the intensity of patients’ depressive syndrome, r=0.59 (p< 0.001)

c. HAMD - Hamilton’s depression scale [35], r=0.51 (p< 0.001)

d. The Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire [33], r=0.42 (p< 0.001)

e. Beck’s Short form of Depression Inventory [36], r = 0.29 (p=0.01)

f. The Dysfunctional Attitudes scale [34], r=0.24 (p=0.02).

In 1998, Terra and Montgomery [37] investigated the effect of a long-term treatment aiming at preventing depression recurrence. The protocol consisted in a double-blind trial to test the efficacy of a one-year fluvoxamine prescription against placebo in patients responding to a six months fluvoxamine pre-treatment. Three scales were used to follow patients’ depression levels and their suicidal risk: Montgomery’s MADRS [23], the HAMD and the RSD. Evaluations were collected at inclusion and 4 times during the six first weeks. Inclusion criteria selected patients presenting with a major depression episode with a minimal MADRS score of 25 and at least two previous major depressive episodes in the five past years. One hundred and three male or female patients were accrued (18 to 70 years) after a response to the six-month pre-treatment. A concurrent validation of the RSD was realized and showed a strong correlation with the MADRS score (r=0.40, p< 0.0001) and especially with the MADRS suicide item (r=0.80, p< 0.0001). With the HAMD suicide item, a similar relationship was observed (r=0.71, p < 0.0001).

In 2002, Ducher and Dalery collaborated to an international prospective randomized trial comparing the efficacy of two treatments (fluoxetine and fluvoxamine) in outpatients presenting with major depressive episodes (minimum HAMD score 17). Accrual occurred in France, Portugal and Holland. Patients were either male or female, aged from 18 to 70 years old and were followed either in public or private consultation. With the 108 French patients, a new concurrent validation was performed, between RSD and Beck’s Suicidal Ideation Scale [14], Hamilton’s depression scale, the clinical scale for the assessment of irritability [38] and the Clinical Anxiety Scale [39] both of Snaith, the Global Clinic Impressions [40] and the Leeds Sleep Evaluation questionnaire [41]. Results were published in 2004 and 2008 [28,31] with the following figures:

a. Beck’s suicidary ideation: r=0.69 (p< 0.0001)

b. Global clinic impressions: r = 0.42 (p< 0.0001)

c. Hamilton’s depression scale: r = 0.35 (p< 0.001)

d. Clinical anxiety scale: r = 0.35 (p< 0.001)

e. Snaith’s irritability, anxiety and depression: r=0.34 (p< 0.001)

f. Leeds sleep evaluation: r=-0.21 (p=0.03)

In the 2008 article, details concerning the correlation with Hamilton’s depression scale items were reported at inclusion, with significant relationships between RSD and:

a. HAMD suicide: r=0.60 (p< 0.0001)

b. HAMD guilt feelings: r=0.38 (p< 0.0001)

c. HAMD agitation: r=0.31 (p=0.001)

d. HAMD slowing down: r=0.25 (p=0.01)

Negative correlation coefficients were noticed between RSD and:

a. HAMD general symptoms: r=-0.41 (p < 0.0001)

b. HAMD genital symptoms: r=-0.24 (p = 0.02)

La Rosa’s survey [27] was performed in 1139 teenagers and young adults (16-25 years old) who consecutively consulted in a preventive health centre controlled by the National Health Insurance System. The study was also supported by the Clinical Psychology and Psychiatry Unit of European Hospital Georges Pompidou (Paris). Among the consultants, 576 were interviewed by psychologists and RSD scales could be rated. Significant correlations (p< 0.001) were found between RSD scores and the various dimensions of the GHQ - General Health Questionnaire [42], Beck’s hopelessness scale [32] and the outcomes of interviews with psychologists. Main correlations (Table 2) confirmed the relationship between the suicidal risk measured by RSD and both psychosocial distress (1st dimension of GHQ and hopelessness) and depression (last dimension of GHQ).

RSD’s predictive validity was assessed in the precited study of Terra and Montgomery [37]. Although the main study endpoint was the decrease of depression, a second endpoint focused on suicide incidence under treatment. Patients included in this trial all presented with a severe depressive episode (MADRS25) within a recurrent depressive disorder and were followed 18 months. For the analysis, they were arbitrarily allocated to two groups according to their RSD level at inclusion. Eighty-eight patients had a RSD score inferior than 7 while 15 presented a higher or equal score. Two complete suicides were observed in the latter group but none in the former. This slightly significant result (p=0.02), has been reported in 2006 by Ducher [29]. These data enabled to calculate sensitivity equal to 100% and specificity to 87%.

Many of the reported publications are in a way evidence of the RSD discriminant validity. But La Rosa’s survey [27], due to its rather large population and the wide range of his investigations, appears to be one of the most interesting studies to demonstrate the discriminant validity of RSD scale. As La Rosa reported, “a high suicidal risk (RSD score≥4) was found in 24% of the studied population. Subjects presenting with a high suicidal risk were characterized by higher levels of GHQ psychosocial distress and GHQ sub-scores as well as hopelessness (p< 0.001). Several biographical antecedents during childhood were significantly associated with suicidal risk: unknown father (p< 0.001), death of parents (p< 0.001), separation from parents (p< 0.001), severe quarrel between parents (p< 0.001), money problems within the family (p< 0.007), disorders related with alcohol consumption in parents (p< 0.016), drug addiction within the family (p< 0.001). Other predictors were several recent stressful events or contexts: violence within the family (p< 0.001), social isolation (p< 0.001), lack of self-esteem (p< 0.002), school difficulties (p< 0.001), educational failure (p< 0.001); as well the notion of a consumption of drugs (p=0,001) or medications: neuroleptics (p< 0.015), antidepressants (p=0.001) and tranquilizers (p< 0.001).” Another study of Ducher [31] offered a same variety of questioning but it concerned 320 adults hospitalized after a suicide attempt in two public emergency services (Simone-Veil hospital, Eaubonne-Montmorency and Sainte-Marie hospital, Clermont-Ferrand). Considering the very high risk of recurrence in these patients during the years following the attempt [43,44], it was a population of choice to test the validity of RSD scale. RSD scale was rated shortly after the arrival in the hospital (median time=16 hours) and several clinical informations were collected:

a. The presence of an associated psychiatric disorder

b. The prescription of antidepressants

c. The possible history of psychiatric hospitalisation

d. The number of previous suicide attempts

e. The type of criticism expressed after the attempt

f. And of course, the appropriate orientation of the patient

Many strong correlations were found between RSD scores and an associated psychiatric disorder (p=0.0009), antidepressant consumption either current (p=0.0002) or past (p=0.0003), previous psychiatric hospitalization (p=0.0009), one or more previous suicide attempts in women (p=0.0003) but not in men (p=0.47). The type of attitude toward the attempt pointed out “the regret the attempt had failed” (p< 10-7) while other attitudes yield similar RSD scores (deny, regret to have committed the suicide attempt, shame, and criticism about the acting: p=0.51). Of course, a strong association was observed between RSD and the patients’ orientation proposed by the psychiatrist of the hospital. Main RSD difference (p< 10-7) was found between a proposition of hospitalization and the two other proposed types of management: either by an out-psychiatrist or by the patient’s consulting physician. RSD was a little higher in patients oriented to an out-psychiatrist than in those addressed to their consulting physician (p=0.016). A last longitudinal discriminant value of RSD scale is reported in the next paragraph.

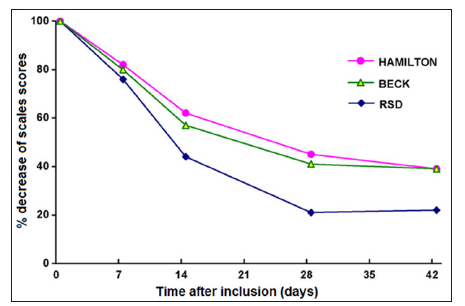

In the pre-cited randomized trial of Ducher, Dalery [30], a longitudinal study of the sensivity to changes under treatment could be performed since evaluations were submitted to the patients periodically after inclusion during the 6-week treatment. Results are shown on (Figure 1). RSD scale tended to be more sensitive than the other scales to predict changes after a treatment [30,31]. RSD was also the only one that enabled to discriminate between the two treatments, here in favor of fluvoxamine (p=0.015) while other scales produced similar outcomes along the treatment period.

RSD scale today possesses a rather important background and a relatively long history. Reported studies corroborate the metrological qualities of this instrument, in different populations (teenagers, adults, both genders, with outpatients or hospitalized ones) and at different times of life (with various patients’ histories, after an attempt or not). The predictive validity of RSD was assessed within a prospective clinical controlled trial. In the literature, most attempts to find predictors of suicide have been performed on cohort analysis but their conclusions when controlled prospectively, have usually failed [45]. Our evidence was obtained with a rather reduced population and the associated 0.02 p-value, although significant, is not that strong. Some effort may then be required to strengthen this outcome and confirm the high sensitivity and specificity found for RSD scale. Somehow, any prospective randomized trial may present ethical pitfalls since patients at suicidal risk cannot be left without treatment/management, and that may be a cause of bias. All the aspects of a standard validation have not been fully investigated, as for example a test-retest or a real inter-judge reliability. A validation of the English version proposed here is still lacking and eventually, this scale will possibly show different metrologic properties in an Anglo-American context. Another challenge consists in confirming the properties of the self- questionnaire derived from the RSD scale. Such a work seems worthwhile for clinical research since selfquestionnaires are more time-sparing and probably less biased. Currently, we have observed a very good reliability between selfevaluations and evaluations made by the psychiatrists. Such a selfquestionnaire appears relevant in a clinical research context where means are always limited. But the psychiatrist that uses it for his daily practice should not forget that the hetero-passation of the scale can represent a good opportunity to construct his interview on a standardized basis and permit a more systematic approach. Due to its passation facility and shortness, RSD can be evaluated repeatedly. It seems then to be an ideal instrument to follow the suicidal crisis and the evolution of the suicidal risk with or without a previous suicidal attempt. In clinical research, it may be an interesting complement with scales like C-CASA and C-SSRS [6], which intend to classify the different kinds of suicide attempts. In one hand, RSD brings additional information and on the other hand, it is also usable when no self-injury can trigger the evaluation.

Figure 1: Percent decrease of the Hamilton depression scale, Beck’s scale for suicidal ideation and RSD during the 6-week treatment with fluvoxamin or fluoxetin. RSD scores diminished significantly faster than the two other scores (p < 0.0001).

RSD is monothematic, concerning only the evaluation of the suicidal risk, and is conceptually independent from underlying mental disorders. It appears to be trans-nosologically and seems particularly in line with the DSM-5 orientations which propose to consider suicide as a separate category disconnected from mental disorders characterization [46]. Since suicide may occur in different contexts and types of psychopathology, RSD scale appears unbiased by other considerations in relation to studied domains. The need today, pointed out by FDA, to include in trials suicide as possible side-effects of any new drug, even not psychotropic, should to our mind not only target a better characterization of self-injuries/attempts but also comprise the evaluation of patients’ dynamic concerning suicide. RSD scale explores this dimension. We suggest then to use this tool in complement to scales that evaluate the suicidal events, either for clinical research purpose or in daily practice in order to enable a better follow-up and management of the suicidal crisis.