Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Reem AH Al Khalifah1, Nasir AM Al Jurayyan*1, Rushaid NA Al Jurayyan2, Mossa NA Al Motawa1, Sharifah DA Al Issa1 and Hessa MN Al Otaibi1

Received: November 12, 2018; Published: November 26, 2018

*Corresponding author: Nasir AM Al-Jurayyan, Department of Pediatrics, Professor and Consultant Pediatric Endocrinologist, Division of Endocrinology, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.11.002081

Childhood hypopituitarism is a clinical syndrome of deficiency in pituitary hormone production. Presentation varies from asymptomatic to acute collapse depending on the etiology, rapidity of onset and predominant hormone involved. A retrospective hospital-based cohort study was conducted at the pediatric endocrine service, King Khalid University Hospital Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (January 1989-December 2017). All the patients (total of 202 patients) who were diagnosed to have hypopituitarism, at the pediatric endocrine service, King Khalid University Hospital Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (January 1989-December 2017). A total of 202 patients were diagnosed to have hypopituitarism. Mean age was 8-9years. Beside congenital causes, diversity of acquired causes were encountered with a non-tumor causes being the commonest. Growth Hormone Deficiency (GHD) was diagnosed in 152 (70.2%) patients. Isolated GHD in 123 patients. Multiple pituitary hormone deficiency was the diagnoses in 29 patients. Central adrenal insufficiency was present in 59(29.2%) patients. Diabetes insipidus associated with hypopituitarism in 24(11.9%) patients. Childhood hypopituitarism is not that rare. High index of suspension coupled with appropriate hormone assay, and head MRI are essential for management.

The pituitary gland is a midline structure located just beneath the optic chiasm. It is composed of two main lobs, the predominant anterior lobe which is known as adenohypophysis and the posterior lobe which is known as neurohypophysis and the vestigial intermediate lobe [1]. Hypopituitarism is a clinical syndrome of deficiency in pituitary hormone production. It might be a life threating condition. It can result from disorders involving the pituitary gland, the hypothalamus or the surrounding structures, such as tumor, inflammation, infection, surgical destruction, radiation, traumatic or vascular insult. It might be associated with birth trauma and perinatal asphyxia or midline defects such as cleft lip, septo-optic hypoplasia and encephalocele. Hypopituitarism could be partial or complete insufficiency of pituitary hormone. Panhypopituitarism refer to involvement of two or more pituitary hormone. However, involvement of one hormone only refer to isolated or partial hypopituitarism. The younger the child is at the time of presentation the more likely the etiology is to be congenital. However, on occasions, congenital forms may present or get diagnosed well after birth and conversely, some children with acquired forms are discovered relatively early in life [2-8]. This article reports on the clinical experience of childhood hypopituitarism from a major teaching hospital, King Khalid University Hospital (KKUH) in the central region of Saudi Arabia over more than 25 years, January 1989 to December 2017. KKUH is affiliated to King Saud University and provides primary, secondary and tertiary health care service to the local population and receives patients’ referral from all over the country.

The medical records of patients who were diagnosed to have hypopituitarism were retrospectively reviewed from January 1989 to December 2017. Data included were age, sex, clinical presentation and results of the relevant laboratory investigations and radiological images. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) was done when appropriate. The diagnosis of hypopituitarism was based on clinical suspicion suggested by the appropriate hormonal testing. The various hormonal testing to assess both the anterior and posterior pituitary gland functions, were performed following the specific protocol [9]. Pituitary function was evaluated after 1-2 months of any neurological procedure. Thyroid function was periodically evaluated as to monitor for thyroid dysfunction.

Descriptive data is provided. Dichotomous data is presented as frequencies and percentage. Statistical Packages for Social Service (SPSS version 21) was used for the statistical analysis of the data.

During the period under review, January 1989 and December 2017, there were 202 patients with hypopituitarism, of these, 142 (70.3%) were males and 60 (29.7%) females. The mean age was 8-9 years (range 0-18 years). MRI brain was performed in 173 (85.6%) of patients. The clinical presentation varied from asymptomatic to symptomatic, the severity of which depends on the hormone deficient and the cause of the disorder. Birth trauma, hypoglycemia, neonatal hepatitis, optic nerve hypoplasia and other midline defects where clues to the diagnosis. Beside congenital causes, a diversity of acquired causes were encountered with a non-tumor causes being the commonest. Those included Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), in three patients and Sub Arachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH), in one patient, central nervous system infections were in two patients, histocytosis in three patients, empty sella syndrome in one patient and various tumors in the hypothalamic pituitary region, the majority of which is craniopharyngioma, constitute 12 (5.9%) patients in our series.

Table 1: Etiology of Growth Hormone Deficiency (GHD) in 152 patients with Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI).

Growth Hormone Deficiency (GHD) was the commonest deficient hormone among other hormones 152 (70.2%) patients. Isolated Growth Hormone Deficiency (IGHD) 123 patients was more common compared Multiple Pituitary Hormone Deficiency (MPHD) in 29 patients (Table 1). Hypothalamic pituitary MRI abnormalities were seen more commonly among cases with MPHD. Central adrenal insufficiency was the second most common hormonal deficiency seen in 59 (29.2%) (Table 2). Diabetes insipidus associated with Panhypopituitarism seen in 24 (11.9%) patients (Table 3). Hypothyroidism presented in 14 (6.99%) patients of these five patients were isolated hormone central hypothyroidism, while gonadotrophic hormone deficiency presented in 8 (3.9%) patients.

1ACTH: Adrenocorticotrophic Hormone.

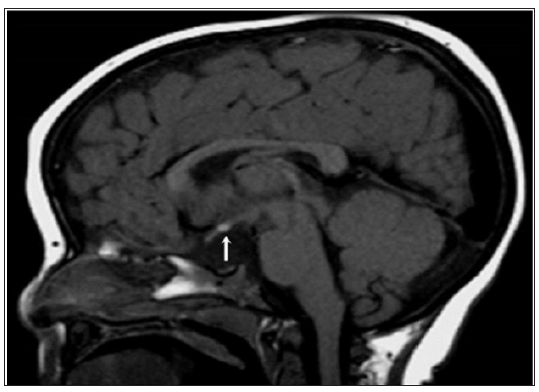

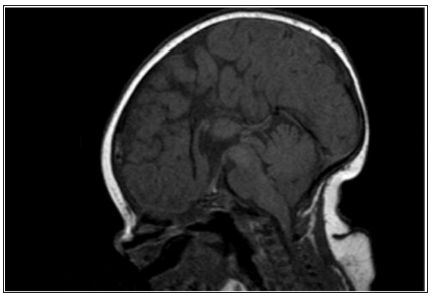

Hypopituitarism is not that rare in children, despite that there is scant data where it is at best limited to case series. A study from Spain documented an incidence and prevalence of hypopituitarism to be 4.21 and 45.5 case per 100000 population respectively. Hypopituitarism follows a smoldering course, unless it has an onset with pituitary apoplexy, hence, more often it is likely to be missed. Hypopituitarism is often associated with increased mortality [10,11]. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan remains the modality of choice for assessing the hypothalamic pituitary region among patient with hypopituitarism. MRI scan precisely diagnose abnormality of the adenohypophysis and neurohypophysis usually the stalk. Normal pituitary MRI shows the anterior pituitary gland as dark structure equal in intensity to gray matter on T1-weighted imaging, while the posterior pituitary gland appears as a white structure, “bright spot” (Figure 1). The “bright spot” correlates well with the clinical presence of Diabetes Insipidus (DI) and it is completely absent in some cases of congenital hypopituitarism or it can be found ectopically located (Figure 2) in which case DI is usually absent. Such radiological findings are sometimes helpful in securing the congenital nature of hypopituitarism. The presence of abnormality in the adenohypophysis and/or neurohypophysis carries important prognostic factor. Patients with such abnormalities usually develop MPHD compared to isolated hormonal deficiency. A spectrum of MRI findings was observed in our series ranging from normal to small or complete absent of anterior or posterior pituitary together with absence or thin stalk (Figure 3) [ 12].

Figure 2: Sagittal T1 weighted Magnetic resonance imaging in a 2.5-year-old girl with multiple pituitary hormone deficiency showing a small anterior pituitary, absent stalk and ectopic posterior pituitary.

Figure 3: Mid-sagittal brain MRI: Agenesis of the dorsal portion of the corpus callosum associated to a rudimentary and hypoplastic ventral corpus callosum. Flat floor of the Sella turcica, slightly excavated with absence of visualization of the stalk and the pituitary in all sequences.

The clinical presentation varies from asymptomatic to acute collapse, depending on the etiology, rapidity of onset and predominant hormones involved [2,5,13,14]. During neonatal period and early infancy, hypoglycemia is considered the most critical presenting feature and perhaps the most common feature of congenital hypopituitarism. In some affected male, congenital hypopituitarism can present at birth as isolated microphallus therefore from isolated GH deficiency or combined GH and gonadotropin deficiency. Additionally, noninfectious hepatitis can be seen in some children with congenital hypopituitarism. This is usually suspected if there is hepatomegaly and abnormal liver enzymes predominantly indicating cholestasis and is confirmed by the presence of characteristic giant-cell transformation of hepatocytes on liver biopsy. The condition is usually self-limiting and remits over the first few months of life without permanent liver damage [15-25].

Septo-optic dysplasia, which also known as de Morsier syndrome, is the most common cause of ‘’midline defect syndrome’’ in which congenital hypopituitarism is one component of this disorder. In its complete form, this syndrome combines hypoplasia or absence of optic chiasm, optic nerves or both, agenesis or hypoplasia of the septum pellucidum, corpus callosum or both (Figure 3) (the function of which is uncertain) in 50% of cases (hence, the designation,”septo”) and hypothalamic insufficiency. The underdevelopment of the optic nerves is associated with variable degree of vision impairment ranging from mild loss to complete blindness.

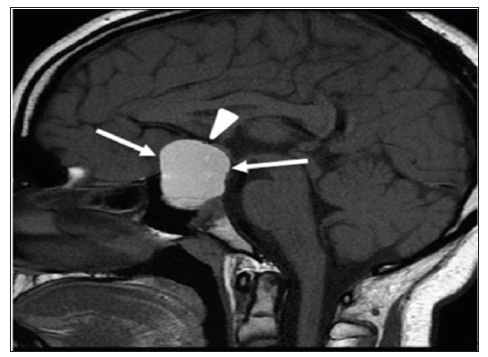

Figure 4: A 13-year-old boy with giant macroprolactinoma. Mid-sagittal brain MRI (T1 weighted image without intravenous contrast) shows a giant macroprolactinoma (arrows) with homogenous high signal intensity indicating hemorrhage. The mass is compressing on optic chiasm (arrowhead).

Various tumors in the hypothalamic pituitary region can lead to hypopituitarism upon presentation. The majority of tumors in our series were craniopharingioma, constitute 12 (5.9%). Commonly they present with symptoms related to mass effect of the tumor on the neighboring structures. However, other tumors in the hypothalamic pituitary region can lead to hypopituitarism such as glioma and astrocytoma. A child in our series presented with recurrent headache and visual impairment at age 13 years proved to have giant macroprolactinoma on MRI (Figure 4) [26-33]. Such findings indicate the importance and the role of pituitary and hypothalamus MRI scan in determining the cause. Langerhans Cell Histocytosis (LCH) is a rare and heterogeneous disease, characterized by accumulation and cloned proliferation of immature dendritic cells in different organs, present in 3 (1.5%) of patients [34,35].

Cancer survivors have a continuous risk for developing hypopituitarism even if they had a normal initial pituitary function. Surgical procedure to remove the tumor may lead to injury to the pituitary gland and result into hypopituitarism. Additionally, radiotherapy treatment for the tumors in the head and neck region may cause damage to the pituitary gland. Different hypothalamic pituitary axis has different sensitivity to radiation [36-40]. Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and Sub Arachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) are being more frequently reported as etiology for hypopituitarism. The incidence of TBI 100-150 in 100,000. Posttraumatic hypopituitarism is observed in 5.4 to 40 % of patient with history of TBI usually presenting as isolated deficiency in most cases. Hypopituitarism has been observed in 19% of patient with ischemic stroke and 47% of patient with SAH presenting as an isolated deficiency in most cases. This could be due to lack of awareness [41-46]. Efforts need to be made to sensitize the clinicians about the existence of hypopituitarism in such patients. Langerhans Cell Histocytosis (LCH) is a rare and heterogeneous disease, characterized by accumulation and cloned proliferation of immature dendritic cells in different organs, present in 3 (1.5%) of patients [35,35].

Central nervous system infections known to have high incidence in developing countries and are known to cause hypopituitarism. In this study hypopituitarism was observed in 2 patients (0.5%). Both of these patients developed hypopituitarism secondary to streptococcal infection [47-50]. Empty sella syndrome usually associated with pituitary hypofunction. Like other cohorts it was a rare diagnosis in our series [51-53]. Growth Hormone Deficiency (GHD), the most common hormonal deficiency and present with a wide spectrum of findings. The endocrine abnormality of GHD manifest either as an isolated deficiency (IGHD) or it may be present as Multiple Hormone Deficiency (MPHD) [54-56]. Central adrenal insufficiency accounts for the second most commonly encounters in this study, however, it is the most lethal. All except one, had multiple anterior pituitary hormone deficiency. This was present in 59 (29.3%) patients [57-59]. One patient passed away at age 4 years from severe hypoglycemia during gastroenteritis despite that she received hydrocortisone stress dose. She was found seizing in her bed with unrecordable blood glucose. She developed cerebral edema followed by DI and passed away because of brain death. Central Diabetes Insipidus (CDI) or Anti-Diuretic Hormone (ADH) deficiency may be associated with hypopituitarism, due to impairment of posterior pituitary gland or hypothalamus in 24 (11.9%) patients. Patients presented with polyuria, polydipsia and high serum sodium of more than or equal 150 mmol\l with diluted urine [60-62]. Furthermore, congenital isolated hypogonadotrophin is extremely rare in this study, 8 (3.9%) patients out of 202 patients, similar to what had been reported in other cohorts [63-64].

This is the largest report of childhood hypopituitarism from Saudi Arabia. High Index of Suspicion coupled with timely and appropriate hormonal assay are essential for the management. A head MRI scan is critical in determining the specific etiology. It needs to be diagnosed and treated early to prevent associated mortality and morbidity. The etiology differs in childhood, as nontumor causes are common than in adults. Supervision and care by a pediatric endocrinologist is crucial and when the child grows older appropriate transition to an adult endocrinologist and experienced reproductive endocrinologist.

The authors would like to thank Mr. Abdulrahman N. Al Jurayyan for his help in preparing the manuscript.