Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Morteza Alibakhshikenari*

Received: November 06, 2018; Published: November 19, 2018

*Corresponding author: Morteza alibakhshikenari, Shahid behehsty university, Tehran, Iran

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.11.002065

A cross-sectional study was done from (April- May 2016) at five health facilities among hemodialyzed patients. Patients undergoing hemodialysis (HD) potentially have an increased risk of infection due to impairment of the immune response and to the multiple transfusion requirements. Using questionnaire brief history was taken from each volunteer patient. By collecting blood, serum was separated and screened for the presence of HBsAg and anti-HCV antibody using ELISA test method. In this study a total of 253 patients were recruited of whom 74.3% were men, the prevalence of HBsAg and HCV antibody were 1.2 and 2.8% respectively, 4% of patients had markers of at least one viral infection marker; with only one patient (0.4%) was being co-infected.

Keywords: HBV; HCV; Hemodialysis

Hepatitis viruses cause potentially life-threatening inflammation of the liver, characterized by acute and chronic forms of liver disease. According to 2013 World Health Organization (WHO) global health impact report of viral hepatitis, more than 240 and 150 million populations were affected by chronic liver disease due to HBV and HCV, respectively [1]. Africa has the second largest number of chronic HBV carriers after Asia and is considered as a region of high endemicity In Ethiopia, the overall prevalence of Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C virus (HCV) among the general population was 7.4% and 3.1% respectively [2]. HBV is partially double stranded DNA, and it is highly prevalent in hemodialysis patients. The high levels of prevalence of HBV infection is mainly due to impact of dialysis and transfused blood units to these patients [3,4]. HCV infection remains frequent in patient receiving long-term dialysis both in developed and less developed countries. Natural history of HCV infection in dialysis patients remains incompletely understood; controversy continues even in patients with intact kidney function.

Defining the natural history of HCV remains difficult for several reasons: the disease has a very long duration, it is mostly asymptomatic, and determining its onset may be difficult. Additional factors can modify the course including co infection with HBV, HIV and alcohol use [5]. HBV and HCV infections are the most important causes of morbidity and mortality in hemodialysis patients [5,6]. Following cardiovascular diseases and bacterial infections, viral hepatitis is the most frequent disease resulting in a complication of hemodialysis treatment [6]. Different infection prevention protocols have changed the incidence of viral hepatitis. For instance, screening of blood donors, erythropoietin therapy, isolation of HBV positive patients, use of dedicated dialysis machines, improved disinfectant procedures, regular surveillance for HBV infection and active HBV vaccination before entering dialysis program [7]. Chronic HD patients have high risk for infection, due to prolonged vascular access.

In an environment where multiple patients receive dialysis concurrently, repeated opportunities exist for person-to-person transmission of infectious agents, directly or indirectly via contaminated devices, equipment and supplies, environmental surfaces, or hands of personnel. Furthermore, HD patients are immune-suppressed [8]. However, HD taken place in various health facilities found in Ethiopia ,no existing data is available regarding on prevalence of HBV and HCV done among HD patients in Addis Ababa. Therefore, this study aims to estimate the prevalence of HBV, HCV among HD patients in Addis Ababa in the period from April-May 2016.

A cross sectional prospective study was conducted in two hospitals in Tehran, Iran, from April-May 2016 by collecting a total of 253 blood samples. Ethical approval was obtained from Departmental Ethics and Research committee of the department of Medical Laboratory Science, College of Health Science, and School of Allied Health Science of shahid behehsty University. Informed consent was found from study subject.

To ensure proper data collection, close ended, multiple choicebased questionnaire was designed both in English and local language which was completed by the principal investigator or/ and HD staffs via patient interview. The collected data includes age, sex, education level, residency; time spent on HD, the number of blood units transfused and HBV vaccination. Reagents which are prequalified by WHO and with sensitivity and specificity of above 90% were revalidated and verified before use. Finally, we used a reagent that gives us a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 97% for both HBV and HCV testing. Before the start of the Hemodialysis procedure 5ml venous blood was collected at the spot. The blood sample was allowed to stand for sufficient time for separation of serum. The sample was then centrifuged, and serum was separated and preserved at -20ºC. The next day the serum sample were transported to AFTGH and tested for HBV and HCV by fully automated Immunoassay analyzer (ARCHITECT i1000SR Abbott park, Illinois, U.S.A) using ready-made reagents for HBsAg and anti-HCV. The presence or absence of Ag and Ab in the sample was determined by comparing the chemiluminescent signal in the reaction to the cut off signal determined from an active calibration. If the chemiluminescent signal in the specimen is greater than equal to the cutoff signal the sample is considered reactive. The positive were rechecked and negative samples were randomly reexamined for confirmation. The results were tabulated and analyzed.

The collected data were entered and analyzed using the statistical package for social sciences software (SPSS v20.0; IBM Crop, Armonk, NY,U.S.A) and also organized and summarized in terms of frequency and the results of the study presented in a descriptive statics.

A total of 253 patients were recruited, of these, 34.4%(n=87) were from Tom higher clinic 20.2%(n=51) were from Santa higher clinic, 18.6%(n=47) Bethel teaching hospital,17.8%(n=45) Tsegereda higher clinic and the remaining 9.0%(n=23) Armed force teaching Hospital.

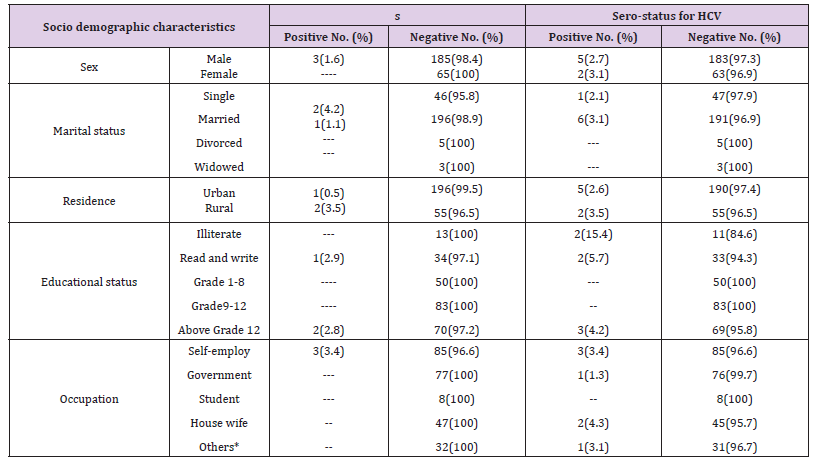

From 253 study participants 74.3% (188/253) were males and 25.7 % (65/253) were females resulting in overall male to female ratio of about 3:1. According to sex distribution, males took the higher proportion in all age groups. Female participants observed higher in age 40-49 years relative to the other age groups. The mean age of the participants was 48.94 years ± 16 SD, with range from 18 to 89 years (Figure 1). In relation to marital status 74.7% (189/253) were married, 17.8% (45/253) were single and 2% (5/253) divorced, whereas the remaining 1.2% (3/253) was widow. Regarding educational status the study revealed two extremes; in which 28.5% (72/253) of the study participants had above grade 12 education and 5.1% (13/253) were not received formal education. The prevalence of HBsAg and anti-HCV Ab in relation with socio- demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: The prevalence of HBsAg and anti-HCV Ab in relation with socio-demographic characteristics April -May 2016.

*dependent, retirement, unemploy.

As shown Table 1, In detecting HBsAg from serum sample the prevalence of HBsAg in hemodyalisis patients was 1.2% (3/253), and prevalence rate in males is 1.6 % (3/188) .The prevalence of HBV by specific age group was highest 5% (2/40) in the age group of 60-69 and was lowest (0%) in the other age groups except 1.3% (1/77) in the age groups 40-49. In addition ,in examining ant- HCV antibody the prevalence in HD patients was 2.8% (7/253), sex specific rate was lower in males 2.7 % (5/188) than females 3.1% (2/65) .And higher prevalence of HCV is shown in specific age group of 40-49 which is 5.5% (4/73), the lowest (0%) counted in age groups >70yrs , 4%(1/25) in the age groups< 30, and 4.4%(1/23) in age group of 30-39 is seen. Regarding, occupational distributions of HBsAg, and anti-HCV antibody positivity was found which is higher among self-employed 3.45% (3/86). Concerned on educational status acquisition of HBV and HCV is similar result was found, with an education level above grade twelve with a frequency of 2/72 (2.7%) and patients who can read and write 1/35 (2.8%).

In relation to living area 0.79% (2/253) was positive for both HBs Ag and anti-HCV antibody respectively in rural dwellers, and in urban dwellers 0.39% (1/253) HBs Ag and 2.0% (5/253) was gotten. With regard to marital status higher number of positivity was scored by singles with a prevalence of 0.79% (2/253) compared to married 0.39% (1/253) for HBs Ag and higher anti-HCV antibody is detected in married individuals 2.4% (6/253) than single status 0.39% (1/253). The assessment of hepatitis C prevalence among hemodyalisis patients was made by detecting anti-HCV Ab. The presence of this marker was taken as measure of infection. Seven 7/253 (2.8%) of the study participants were positive for anti-HCV antibody.

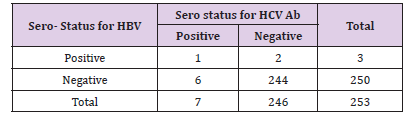

In this study 0.4% (1/253) of the participants was positive for both sero-markers HBsAg and Anti-HCV. The gender profile for these participants, who have both HBV and HCV infections, showed a male aged within 60-69 years Table 2.

Table 2: Optic nerve abnormalities on MRI and VEP.The prevalence of HBV/HCV co-infection among HD April-May 2016.

In all of the centers, new cases of ESRD patients are tested for HBsAg and anti- HCV before initiation of HD and according to the result they are directed to the suitable HD area and machine within the center. Study participants in this study had been attending the procedure from 4 weeks to 4 years’ time duration. HD centers operate in two shifts; the morning shift was from 8 to 12 A.M, the noon shift from 12 A.M to 4 P.M. Physicians prescribe the frequency of HD for each patient accordingly. Most of study participants undergo two HD sessions per week (54.9%), followed by three HD sessions (43.5%) and the minimum number of sessions was one per week (1.6%) Table 3.

Among study participants 58 % (147/253) had history of Hypertension, followed by 21.4% (55/253) had both Hypertensive and Diabetic cases and the remaining 11.2 % (28/253) was Diabetic. Table 4 illustrates distribution of medical history of patients under hemodyalisis at the five HD centers.

*Hypertensive and diabetic ** infections and kidney stone *** unknown cause

Viral hepatitis remains a major hazard for both patients and medical staffs of HD units. HCV became the major form of viral hepatitis among HD patients especially after the decline in incidence of HBV infection due to several factors including vaccination and screening of transfused blood for HBV [9]. As a case in point different studies made in different countries attests to this. For example, high prevalence of HBV (2.6%) and HCV (31.1%) in maintenance hemodyalisis patients [10] was reported in Libiya, HCV prevalence rates of 7% and 22% in HD patients have also been reported in Iran [7] and Palestine [9] respectively, and 7.8% HBV prevalence rate reported in Cameron [8]. Similarly, different studies conducted in Ethiopia found that Hepatitis B and C virus infections are significant community health problems in the country [11-15]. Contrary to these, the current study found low prevalence rate of HBV (1.2%) and HCV (2.8%) as compared from the general population which is 7.4% for HBV and 3.1% for HCV [2]. In addition, infections among patients under hemodialysis in comparison to the results of the studies highlighted above.

Different studies confirmed that length of HD and use of shared machine was associated with high HBV and HCV acquisition in HD patients [5,7]. In this study low prevalence of HBV and HCV among hemodialysis patients was relatively low as compared to the Ethiopian general population and the other hemodialyzed patients in other part of the world as we mentioned above, may be due to the shorter duration of patients under hemodialysis procedure and separated usage of HD machine. Moreover, all of the five HD centers follow similar procedures in the use of disposable needle for artery-vein fistula, and precautions to prevent the exposure to nosocomial infection through avoidance of sharing multi-dose vials or blood contact equipment like filters and different tubing; this could be another probable cause. Age distribution of ESRD patients in this study showed half of the cases were below fifty years of age. A comparable age distribution and results was seen in other studies [7,16]. A high prevalence of HBV was recorded in the age group 60- 69 with a prevalence of 4.9% (2/41) while in our finding it was 5% (2/40). The reason could be related with the low immunity of the age group to infection with the hepatitis viruses.

In terms of sex specific the frequency of HBV and HCV prevalence on HD patients was higher among males than females. This is also consistent with studies made in Iran. The greater frequency of ESRD and HBV infection in males as compared to females could be a reflection of the tendency of males more coming for treatment than females in our setting. Comparable results were reported in a number of studies concerning HBV infection, Ethiopia 4.9% (273/5592) in males and 3.3 % (25/769) in females [14]. Related to the presumed cause of ESRD the majority 56.5% related with Hypertension in the study population. In HD centers HCV is a major problem and is prevalent in both pre-dialysis population and more significant in patients on maintenance of HD [16-18]. Because HCV infections are of special public health concern and the infected person has a potential reservoir for its transmission, the prevalence of HCV among HD patients is higher (2.8%). This rate is comparable with the study done in different countries in which prevalence was between (3-7%) [19-22] and lower than of Brazil (46.7%) [20]. In summary this study has found relatively low prevalence of HBV and HCV in HD patients. Using ELISA test kit for analysis of hepatitis B and hepatitis C than commercially available rapid test kits gives strength and Hemodialysis patients with occult HBV infection were not identified, and limited number of study sites were the limitation of the study.

This study has found lower prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection among hemodyalisis patients visiting five selected HD centers.

Recommendations

a) Adherence to comprehensive infection control program include infection control practices, effective follow up procedure, routine serological testing and immunization, surveillance, training and education.

b) Further studies are recommended to investigate associated risk factors regarding the prevalence of HBV and HCV in HD patients

c) Practice of health workers in HD centers should be investigated regarding infection transmission.

d) Finally further studies are needed to define hepatitis virus’s genotypes between HD patients.

The study protocol was approved by Departmental Ethics and Research committee of the department of Medical Laboratory Science, College of Health Science, and School of Allied Health Science of shahid behehsty University. Permission was obtained from the health facilities administrator. Subject was recruited after they become informed about the objectives and use of the study and after they give informed consent patient results are confidential only respective individuals could evaluate or see result.